Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

The European Journal of Psychiatry

versión impresa ISSN 0213-6163

Eur. J. Psychiat. vol.26 no.4 Zaragoza dic. 2012

https://dx.doi.org/10.4321/S0213-61632012000400005

Olanzapine as an add-on treatment in migraine status: A randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot study

Johana Mogollón*; Ana Serrano*; Alix Padrón de Freitez**; Euderruh Uzcátegui*; Trino Baptista***

* Department of Psychiatry, Los Andes University Medical School, Mérida. Venezuela

** Department of Neurology, Los Andes University Medical School, Mérida. Venezuela

** Department of Physiology, Los Andes University Medical School, Mérida. Venezuela

Sponsor: FONACIT, Caracas, Venezuela, grant G-2005-000-384.

ABSTRACT

Background and Objectives: The authors assessed the effectiveness of olanzapine as an adjunctive treatment in migraine status.

Methods: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Subjects consecutively admitted to a day program of tertiary referral (97 % women; age: 35.8 ± 11.8 yrs.) were assigned to olanzapine (n = 14, 5-10 mg/day) or placebo (n = 17), added to the standard neurological treatment during 4 days. Primary measures were the change in pain and the return to regular daily activities. Secondary and safety measures were the magnitude of sedation, constipation and glucose level changes.

Results: No significant differences were observed in the overall analysis of the primary measures. However, change in pain significantly correlated with age in the olanzapine group (p = 0.03). In the > 40 year-old group, olanzapine (n = 5) displayed a significantly higher reduction in pain than placebo (n = 4) at days 1 (p = 0.048) and 3 (p = 0.045). No significant differences were observed in the change of serum glucose levels.

Conclusions: Olanzapine was well tolerated and sedation was welcomed by most subjects. The positive effect in subjects aged > 40 years awaits replication.

Key words: Migraine status; Atypical antipsychotics; Adjunctive therapy.

Introduction

The management of migraine attacks in neurological and psychiatric patients is a formidable challenge1-3. Therapy consists of analgesics such as aspirin, acetaminophen, opioids, steroidal and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and migraine-specific agents, such as ergotamine, dihydroergotamine and the triptans. Very often, a wash-out, drug-free period is necessary to recover drug responsiveness, with high intra- and inter-individual variability1.

There is a long off-label, anecdotic tradition in using antipsychotics in the treatment of migraine attacks4,5. Typical antipsychotics are limited by the risk of unwanted neurological effects. Atypical antipsychotics display a favorable profile in open labeled studies and are promising agents6-13. Olanzapine has easy dosage, analgesic, sedative and ansiolytic properties which are related to its effects on serotonergic, dopaminergic and histaminergic neurotransmission1,4,5. No randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial with olanzapine has been published.

Methods

This add-on, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study was conducted from January 1st to December 31st, 2010 at the Migraine Clinic for tertiary referral at Los Andes University Hospital, Mérida, Venezuela. It was approved by the local Ethic Committee, and participants signed an informed consent for voluntary participation.

Procedure

Consecutively admitted patients aged >18 years consulting after failed non-standardized pharmacological treatment for a migraine attack lasting at least three consecutive days and diagnosed of Status Migrainosus14 were randomized either to olanzapine (Zyprexa Zydis®, in 5-mg tablets) or identical placebo pills during 4 days. The neurologist in-charge used the drug treatment considered as the best for a particular patient.

Only the study coordinator (TB) knew the treatment allocation (olanzapine or placebo) but he did not conduct any clinical evaluation. Randomization was achieved by alternating treatment distribution every first, second or third consulting subject in the initial, middle and last phases of the study respectively.

Olanzapine (5-10 mg, a dose range expected to induce mild sedation) or placebo were administered b.i.d. Each subject was contacted daily by phone at 17:00 hr by J.M. who administered the scales and by the study coordinator who adjusted the dose according to the sedation level.

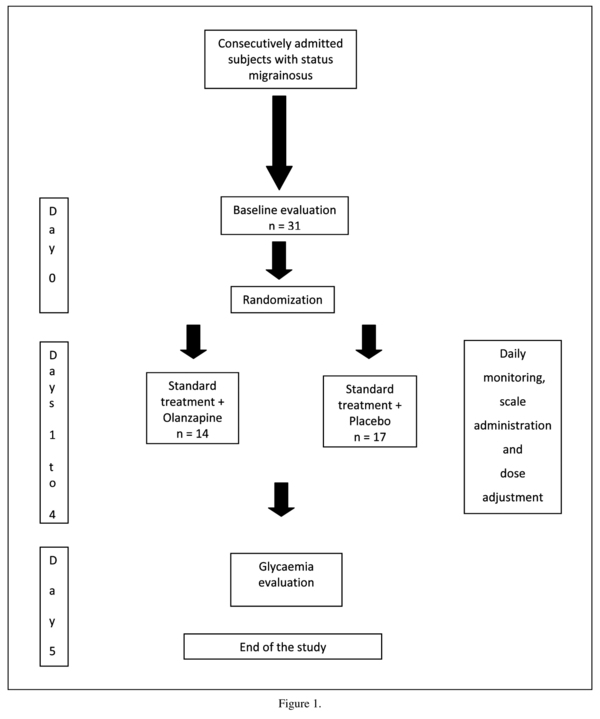

At day 0 (figure 1), we assessed in the morning the migraine attack duration, incapacity (number of days without working or attending school) and the administered pharmacological treatment.

The primary measure was change in pain assessed with an analogical visual scale (AVS) where "0" was no pain and "10" was unbearable pain. Daily individual scores were obtained by subtracting punctuation at days 1 to 4 from basal values at day 0.

Secondary measures with unstandardized scales were:

a) Return to normal life and constipation, with 4 items: normal, intermediate, barely and none.

b) Sedation, with "0" as no sedation and "10" as maximal in a VAS.

c) Since olanzapine tends to induce hyperglycemia15, serum glucose levels were assessed at day 0 and 5.

Change in pain was analyzed with an ANOVA for repeated measures, with treatment (olanzapine or placebo) and age (under or over 40 yrs.) as between subject factors. Effect size was calculated according to Cohen. Glucose level change and sedation were analyzed with the two-tailed t test for unrelated samples. Return to normal life and constipation were analyzed with the Mann-Whitney U test. Correlations were conducted with the Spearman coefficient. Results were considered significant when p < 0.05.

Results

A Last Observation Carried Forward protocol was used, but it was only applied in one subject. The study was completed by 14 olanzapine subjects (age: 35.7 ± 11.8 yrs; 13 females, 1 male) and 17 placebo subjects (age: 35.2 ± 8.3 yrs; 17 women). Seven patients (23%) had migraine with aura and 24 (77%) without aura (p = 0.15).

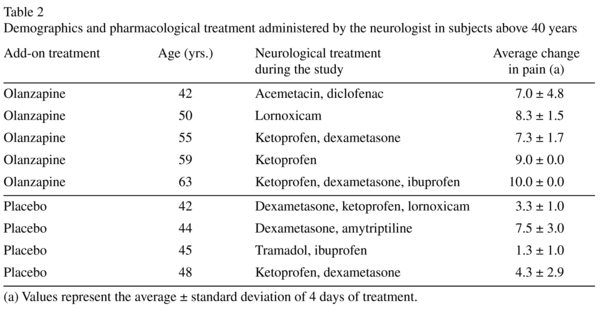

In the overall analysis no between-group significant differences were observed in pain change: f (1, 26) = 1.9, p = 0.18. However, a positive association was observed between pain change and age only in the olanzapine group: day 1: bivariate correlation analysis: (r [14] = 0.58, p = 0.031); day 3 (r = 0.68, p = 0.008). A significant interaction was observed between age and treatment f (1, 26) = 6.9, p = 0.01. Specifically, pain reduction was significantly higher after olanzapine administration in subjects aged > 40 yrs (Table 1), with a medium-large effect size (0.6-0.7). Baseline pain intensity and duration, degree of disability and basal glycaemia did not differ between the treatments in the > 40 yr. subjects (p > 0.05). Demographics and pharmacological treatments in this group are described in Table 2; olanzapine-treated patients were older: 53.8 ± 8.1 vs. 44.8 ± 2.5, t (7) = 2.1, p = 0.07.

No significant differences were observed in constipation intensity and return to normal life. However, sedation was more pronounced at day 1 after olanzapine (p = 0.023) and at day 4 after placebo (p = 0.025). No significant difrerences were observed in glucose change between the groups (p = 0.7).

When the single male subject was excluded, the results were identical (data not shown).

Discussion

We report a positive effect of olanzapine on pain management in subjects older than 40 years and a safe profile. Sedation was considered as positive by most subjects, and glucose change was similar in both groups. The discussion will focus on women who constituted most of our sample.

The influence of age may be related to the hormonal environment of perimenopause and menopause. Low serum estradiol levels associated to the lutheal phase and perimenopause may be involved in migraine aggravation16. Normal17 or elevated estradiol levels18 are observed during olanzapine administration, but these effects are unlikely to be involved, since the estradiol level change occurred after prolonged treatment. Besides, olanzapine is devoid of effects on 5HT1B and 5HT1D receptors19 which are critical for the antimigraine effects16. Therefore, the beneficial effects observed here may be related to antihistaminic effects or serotonin and dopamine transmission modulation20.

Since the > 40 year old group comprised only 5 women, our findings must be considered as preliminary. Given the potential efficacy and safety of olanzapine in migraine attacks, this study should be replicated and extended.

Acknowledgments

Eli Lilly Venezuela provided the placebo pills.

Conflicts of interests: Neither the sponsor agency nor Eli Lilly participated in the design, data analysis or manuscript preparation.

References

1. Buse DC, Rupnow MFT, Lipton RB. Assessing and managing all aspects of migraine: migraine attacks, migraine-related functional impairment, common comorbidities, and quality of life. Mayo Clin Proc 2009; 84: 422-435. [ Links ]

2. McIntyre RS, Konarski JZ, Wilkins K, Bouffard B, Soczynska JK, Kennedy SH. The prevalence and Impact of migraine headache in bipolar disorder: results from the Canadian Community Health Survey. Headache 2006; 46: 973-982. [ Links ]

3. Baptista T, Uzcátegui E, Arapé Y, Serrano A, Mazarella X, Ramirez CI, et al. Frequency of migraine in some mental disorders: concurrent comparisons with the general population in Venezuela. Investigación Clínica 2012; 53: 38-51. [ Links ]

4. Dusitanond P, Young WB. Neuroleptics and migraine. Cent Nerv Syst Agents Med Chem 2009; 9: 63-70. [ Links ]

5. Siow HC, Young WB, Silverstein SD. Neuroleptics in headache. Headache 2005; 45: 358-371. [ Links ]

6. Boeker T. Ziprasidone and migraine headache. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159: 1435-1436. [ Links ]

7. LaPorta LD. Relief from migraine headache with aripiprazole treatment. Headache 2007; 47: 922-926. [ Links ]

8. Datta SS, Kumar S. Clozapine-responsive cluster headache. Neurol India 2006; 54: 200-201. [ Links ]

9. DelBello MP, Adler CM, Whitsel RM, Standford KE, Strakowski SM. A 12-week single-blind trial of quetiapine for the treatment of mood symptoms in adolescents at high risk for developing bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2007; 68: 789-795. [ Links ]

10. Krymchantowski AV, Jevoux C, Moreira PF. An open pilot study assessing the benefits of quetiapine for the prevention of migraine refractory to the combination of atenolol, nortriptyline, and flunarizine. Pain Med 2010; 11: 48-52. [ Links ]

11. Rozen TD. Olanzapine as an abortive agent for cluster headache. Headache 2001; 41: 813-816. [ Links ]

12. Silberstein SD, Peres MF, Hopkins MM, Shechter AL, Young WB, Rozen TD. Olanzapine in the treatment of refractory migraine and chronic daily headache. Headache 2002; 42: 515-518. [ Links ]

13. Hill CH, Miner JR, Martel ML. Olanzapine versus droperidol for the treatment of primary headache in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2008; 15: 806-811. [ Links ]

14. Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders. Cephalalgia 2004; 24 (suppl. 1). [ Links ]

15. Fernandez-Egea E, Miller B, Garcia-Rizo C, Bernardo M, Kirkpatrick B. Metabolic effects of olanzapine in patients with newly diagnosed psychosis. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2011; 31: 154-159. [ Links ]

16. Galletti F, Cupini LM, Corbelli I, Calabresi P, Sarchielli P. Pathophysiological basis of migraine prophylaxis. Prog Neurobiol 2009; 89:176-192. [ Links ]

17. Brandes JL. The Influence of estrogen on migraine: a systematic review. JAMA 2006; 295: 1824-1830. [ Links ]

18. Canuso CM, Goldstein JM, Wojcik J, Dawson R, Brandman D, Klibanski A, et al. Antipsychotic medication, prolactin elevation, and ovarian function in women with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Psychiatry Res 2002; 111: 11-20. [ Links ]

19. van Bruggen M, van Amelsvoort T, Wouters L, Dingemans P, de Haan L, Linszen D. Sexual dysfunction and hormonal changes in first episode psychosis patients on olanzapine or risperidone. Psychoneuroendocrinol 2009; 34: 989-995. [ Links ]

20. Stahl SM. Antipsychotic agents. In: Essential Psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific Basis and Clinical Applications. 2o edition. Cambridge University Press; 2005. p. 401-458. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Trino Baptista

Department of Physiology

Los Andes University Medical School

Mérida, Venezuela

E-mail: trinbap@yahoo.com

Received: 22 December 2011

Revised: 6 April 2012

Accepted: 18 May 2012