Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

The European Journal of Psychiatry

versión impresa ISSN 0213-6163

Eur. J. Psychiat. vol.29 no.3 Zaragoza jul./sep. 2015

https://dx.doi.org/10.4321/S0213-61632015000300002

Trajectories of complicated grief

Ilsung Nam

Hallym University Institute of Aging, Chunchun-si, Kangwon-do. South Korea

This research was supported by Hallym University Specialization Fund (HRF-S-21).

ABSTRACT

Background and Objectives: In the discussion of apparent similarities between symptoms of grief and depression, research and theory have often confounded these two constructs because, as a construct, grief is distinct from depression and because these two constructs may have distinct trajectories. This study examines the trajectories of complicated grief and associated risks and the relationship between trajectories of complicated grief and depression.

Design: Longitudinal.

Setting: Intervention methods for enhancing family caregiving for persons with dementia.

Participants: A total of 221 participants of the Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health project.

Measurement: The Inventory of Complicated Grief.

Results: The results based on group-based mixture modeling identify two distinct trajectories of grief (persistently high and low) and three distinct trajectories of depression (persistently high, moderate, and low). There were significant differences between the proportion of grief trajectory membership and that of depression trajectory membership, indicating distinct patterns over time.

Conclusions: Noteworthy is the significant difference between the proportion of grief trajectory membership and that of depression trajectory membership, indicating differences in distinct patterns over time.

Key words: Complicated grief; Depression; Trajectory; Bereavement; Classification.

Introduction

Previous studies have demonstrated that trajectories of grief vary during bereavement. Although traditional theories of the transition process of grief assume normal changes in patterns of grief over time, recent studies have argued that bereaved individuals may exhibit individual differences in grief over time and presented different and meaningful trajectory groups based on their samples, suggesting different risks to be associated with trajectory membership. An important theoretical limitation of these findings is that most studies have examined trajectories of depressive symptoms of bereaved individuals, whereas some have found that, as a construct, grief is distinct from other psychological symptoms such as depression and anxiety1-5. As shown in Table 1, previous studies have identified several different trajectories for each sample, demonstrating differences in changes in depression over time, and most of the trajectory membership can be characterized by low levels of depression over time such that only a small proportion can be characterized as high-depression trajectory groups. This raises the question of whether trajectories of grief are different from those of depression.

No study has specifically examined how bereaved individuals show different patterns of complicated grief over time. In this regard, this study extends the literature by providing a better understanding of how individuals who lose a loved one can be better cared for. The study examines the trajectories of complicated grief and associated risk factors and investigates the relationship between the trajectories of complicated grief and depression.

Methods

The data set

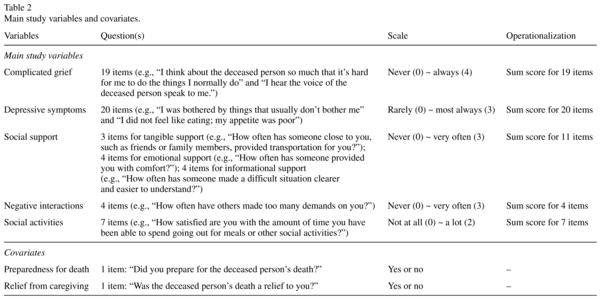

The data set included a total of 221 caregivers recruited from the Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer's Caregiver Health (REACH) project. These caregivers lost family members with dementia during the course of this study. A total of 1,222 caregiver-care recipient dyads recruited between 1996 and 2000 from six sites across the U.S. (Miami, FL; Boston, MA; Memphis, TN; Birmingham, AL; Palo Alto, CA; and Philadelphia, PA) were subjected to follow-ups in assessment intervals of 6, 12, and 18 months. Among these 1,222 caregivers, 221 lost their care recipients during the study period. Complicated grief was measured using the Inventory of Complicated Grief 4, and depressive symptoms were measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale11. Covariates were used to examine any significant differences between grief trajectory membership, including demographic factors (e.g., sex, age, income, and the education level), social factors (e.g., social support, negative social interactions, and social activities)12, and bereavement-related factors (e.g., preparedness for death and relief from caregiving). Table 2 describes these variables.

Statistical analysis

The analysis had four steps. The first step estimated grief trajectories within the data to determine an optimal number of trajectory groups. A semi-parametric group-based mixture modeling method was employed to identify grief trajectories of bereaved caregivers over time by using the STATA TRAJ plugin13. Censored normal distributions were applied to this modeling, which was potentially censored by a scale minimum or maximum or both. An optimal number of groups were determined using the Bayesian information criteria (BIC), with lower values indicating a better fit14. Then a mixture modeling test was conducted for depression measures to determine any differences in trajectory patterns between depression and grief. The second step included a univariate analysis for relationships between trajectory group membership and covariates. The chi-square test was conducted for nominal covariates, and the t-test or a one-way ANOVA was used for continuous covariates. The third step entailed a logistic regression analysis to predict grief trajectories based on baseline covariates (i.e., the first measure after death). The final step involved a chisquare test to examine the relationship between grief trajectory membership and depression trajectory membership.

Results

The mean age of the sample was 63.66 years (SD = 13.38), and 84% were female. In addition, 65.78% were white, 56.89% were high school graduates, 25.78% were employed, and 50.22% were spouses. Further, 43.56% had an annual income of less than $20,000, and 54.67% reported some economic hardship (Table 3).

Two distinctive trajectory groups of grief were identified based on the optimal BIC value (-1,484.98) (Figure 1). These two groups were named as follows: persistently high grief (n = 59, 26.22%) and low grief (n = 166, 73.78%).

There were significant differences between the two trajectory groups in terms of covariates, namely age, the education level, social activities, negative interactions, and the extent to which the bereaved were prepared for death. High-grief participants were younger, less educated, more likely to participate in social activities, and less likely to pursue negative social interactions. In addition, they were less likely to consider death as a type of relief for the bereaved. Similarly, they were not prepared for death (Table 4).

There were significant differences between grief trajectory group membership and depression trajectory group membership. Those in the high-grief trajectory group were more likely to belong to the high-depression trajectory group, whereas those in the low-grief trajectory group, to the low-depression trajectory group. The high-depression trajectory group included more participants from the high-grief trajectory group than from the low-grief trajectory group (χ2(2) = 37.61, p < 0.001).

Discussion

An increasing number of studies have suggested that trajectories of emotions vary during bereavement. No study has estimated grief trajectories during bereavement, and in this regard, the present study extends the literature by examining these trajectories. As hypothesized, there were distinctly homogeneous trajectory groups of grief. There were two trajectory groups of grief: persistently high and low. Consistent with the findings of previous research on depression trajectories during bereavement, the results show that a majority of the participants presented persistently low levels of grief over time, whereas 26.34% of the participants showed persistently high levels. In addition, the covariates associated with grief trajectory membership included age, the education level, social activities, negative interactions, the extent to which death could be considered a relief to the deceased and bereaved, expectations of death, and preparedness for death. Further, there were three depression trajectory groups. Finally, there was a significant difference between grief and depression trajectory memberships.

The results for the probability of grief trajectories during bereavement are consistent with the findings of previous studies showing grief trajectories to vary during bereavement and thus to be distinct. As briefly mentioned earlier, traditional grief theories portray one normative response in every stage of the grieving process over time. This suggests that failing to generate a normative response can lead to the emergence of an abnormal form of grief. However, the results provide no support for this explanation. The high-grief group started at a high level and persisted for two years. By contrast, the low-grief group started at a low level and maintained it. Indeed, at least for bereaved caregivers, grief responses to loss over time may depend on variables before death or in the initial phases of bereavement. This may be explained by the stress-coping framework, which highlights the role of coping with stressors to overcome psychological disturbances and move to the normal phase of grief§. The results provide evidence supporting the notion of increased or decreased levels of grief immediately after death tending to persist and emphasize the importance of immediate intervention after bereavement to help bereaved individuals cope with stressors.

The results indicate several factors associated with trajectory group membership. Younger and less educated grievers were more likely to belong to the high-grief trajectory group. These results are consistent with the findings of Schulz et al15. In addition, the effects of social activities and negative interactions were associated with trajectory group membership. To the author's knowledge, no study has examined the effect of social activities on grief. Based on the dual-process model, social activities during bereavement may be a coping strategy for restoring bereaved individuals to a new life without the deceased (i.e., restoration-related coping). However, future research should examine this through an empirical analysis, particularly if those more likely to engage in social activities have better coping skills for loss-oriented stressors (e.g., grief work and intrusion). In addition, no study has examined the effect of negative interactions during bereavement. Among non-bereaved participants, negative social interactions were associated with depressive symptoms17,18, and the magnitude of test statistics was high [χ2(1) = 14.699, p < 0.001]. In this regard, future research should empirically test the effects of negative social interactions, particularly those of patterns and characteristics of these interactions, on grief.

Some bereavement-related variables were associated with trajectory group membership, namely the extent to which the death could be considered a relief and the preparedness of the bereaved. Previous studies have observed that not all caregivers feel relieved from the burden of caring or the psychological burden of watching a loved one suffer from severe pain after death7,19,20. Indeed, a majority of bereaved individuals may not exhibit some relief by the death of a loved one. The results of the present study indicate that those with lower levels of relief from death were more likely to belong to the high-grief trajectory group. Therefore, intervention options may be developed to target individuals who perceive death as not a relief to the deceased. For example, relief may be considered a core component to be screened and dealt with in cognitive behavioral therapy for the bereaved.

Noteworthy is the significant difference between the proportion of grief trajectory membership and that of depression trajectory membership, which indicates that their distinct patterns varied over time. In fact, among those belonging to the high-grief group, about 30% belonged to the low-depression trajectory group. This suggests that such people may be ignored in targeted service delivery that screens beneficiaries only by depression. Therefore, grief as well as depression should be screened while considering individuals for the delivery of bereavement services, and tailored interventions should be delivered to those with intense grief to avoid their development of persistently high levels of grief.

This study has some limitations. All participants were prior caregivers, and therefore the results may not be generalizable to more diverse samples because of the participants' caregiving experience before death, particularly at the end of the life stage. According to a recent study, many caregivers anticipate and grieve prior to the death of their relatives21. It is possible that grieving before death influences the level of complicated grief after death. Therefore, pre-loss grief may require a careful assessment for a more precise analysis. Another limitation is the relatively short study period. In this regard, future research should consider a longer analysis period and a larger sample size. Previous studies have reported prolonged grief in sizable minorities who lose their loved ones22,23. In this regard, future research should consider data sets of longer durations to better elaborate on longitudinal patterns of complicated grief.

Despite these limitations, the results provide important insights into the long-term trajectory of emotions during bereavement, thereby offering an enhanced understanding of bereavement-related psychological distress and facilitating the development of long-term intervention options for the bereaved. Understanding the difference between grief and depression trajectories can shed important light on ways to differentiate grief from depression, particularly in terms of changing patterns over time and their constructs. In addition, understanding distinct trajectories of grief over time is crucial for conducting appropriate screening for grief and depression and for providing effective intervention options for bereaved individuals experiencing one of the most difficult periods of their lives.

Conflict of interest

The author claims no conflicts of interest.

§The dual process of the model of bereavement coping, introduced by Stroebe and Schut16, hypothesizes the role of coping in bereavement as both loss-oriented and restoration-oriented. According to the model, bereaved individuals have to cope with both loss- and restoration-oriented stressors by oscillating their coping between both stressors to maintain some normal state of life after the loss of a loved one.

References

1. Boelen PA, van den Bout J. Complicated grief, depression, and anxiety as distinct postloss syndromes: A confirmatory factor analysis study. Am J Psychiatr. 2005; 162(11): 2175-7. [ Links ]

2. Dillen L, Fontaine JR, Verhofstadt-Denève L. Confirming the distinctiveness of complicated grief from depression and anxiety among adolescents. Death Stud. 2009; 33(5): 437-61. [ Links ]

3. Golden AM, Dalgleish T. Is prolonged grief distinct from bereavement-related posttraumatic stress? Psychiatr Res. 2010; 178(2): 336-41. [ Links ]

4. Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Reynolds CF 3rd, Bierhals AJ, Newsom JT, Fasiczka A, Frank E, Doman J, Miller M. Inventory of Complicated Grief: A scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatr Res. 1995; 59(1): 65-79. [ Links ]

5. Prigerson HG, Frank E, Kasl SV, Reynolds CF 3rd, Anderson B, Zubenko GS, Houck PR, George CJ, Kupfer DJ. Complicated grief and bereavement-related depression as distinct disorders: Preliminary empirical validation in elderly bereaved spouses. Am J Psychiatry. 1995; 152(1): 22-30. [ Links ]

6. Aneshensel CS, Botticello AL, Yamamoto-Mitani N. When caregiving ends: The course of depressive symptoms after bereavement. J Health Soc Behav. 2004; 45(4): 422-40. [ Links ]

7. Bonanno GA, Wortman CB, Lehman DR, Tweed RG, Haring M, Sonnega J, Carr D, Nesse RM. Resilience to loss and chronic grief: A prospective study from preloss to 18-months postloss. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002; 83(5): 1150-64. [ Links ]

8. Galatzer-Levy IR, Bonanno GA. Beyond normality in the study of bereavement: Heterogeneity in depression outcomes following loss in older adults. Soc Sci Med. 2012; 74(12): 1987-94. [ Links ]

9. Tang ST, Huang GH, Wei YC, Chang WC, Chen JS, Chou WC. Trajectories of caregiver depressive symptoms while providing end of life care. Psychooncology. 2013; 22(12): 2702-10. [ Links ]

10. Zhang B, Mitchell SL, Bambauer KZ, Jones R, Prigerson HG. Depressive symptom trajectories and associated risks among bereaved Alzheimer disease caregivers. Am J Geriatr Psychiatr. 2008; 16(2): 145-55. [ Links ]

11. Radloff LS: The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977; 1(3): 385-401. [ Links ]

12. Krause N. Negative interaction and satisfaction with social support among older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1995; 50(2): 59-73. [ Links ]

13. Jones BL, Nagin DS. A note on a Stata plugin for estimating group-based trajectory models. Sociol Methods Res. 2013; 42(4): 608-13. [ Links ]

14. Jones BL, Nagin DS, Roeder K. A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Sociol Methods Res. 2001; 29(3): 374-93. [ Links ]

15. Schulz R, Boerner K, Shear K, Zhang S, Gitlin LN. Predictors of complicated grief among dementia caregivers: A prospective study of bereavement. Am J Geriatr Psychiatr. 2006; 14(8): 650-8. [ Links ]

16. Stroebe M, Schut H. The dual process model of coping with bereavement: Rationale and description. Death Stud. 1999; 23(3): 197-224. [ Links ]

17. Krause N, Rook KS: Negative interaction in late life: Issues in the stability and generalizability of conflict across relationships. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003; 58(2): 88-99. [ Links ]

18. Newsom JT, Schulz R. Caregiving from the recipient's perspective: Negative reactions to being helped. Health Psychol. 1998; 17(2): 172-81. [ Links ]

19. Bonnano GA, Mancini AD. Beyond resilience and PTSD: Mapping the heterogeneity of response to potential trauma. Psychol Trauma. 2012; 4(1): 74-83. [ Links ]

20. Schulz R, Boerner K, Shear K, Zhang S, Gitlin LN. Predictors of complicated grief among dementia caregivers: a prospective study of bereavement. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006; 14(8): 650-8. [ Links ]

21. Hebert RS, Dang Q, Schulz R. Preparedness for the death of a loved one and mental health in bereaved caregivers of patients with dementia: findings from the REACH study. J Palliat Med. 2006; 9(3): 683-93. [ Links ]

22. Prigerson HG, Horowitz MJ, Jacobs SC, Parkes CM, Aslan M, Goodkin K, et al. Prolonged grief disorder: Psychometric validation of criteria proposed for DSM-5 and ICD-11. PLOS Med. 2009; 6(8): e1000121. Erratum in: PLoS Med. 2013; 10(12). [ Links ]

23. Shear MK, Mulhare E. Complicated grief. Psychiatr Annals. 2008; 38(10): 662-70. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Hallym University Institute of Aging

Chunchun-si, Kangwon-do

South Korea

011-82-33-248-3098

E-mail: ilsungn@gmail.com

Received: 6 January 2015

Revised: 30 April 2015

Accepted: 16 May 2015