Introduction

Men's intimate partner violence (IPV) against women is a global public health problem that has devastating effects on the health and wellbeing of women and children.1 2

The health system, especially primary health care services, can play a key role in preventing and responding to IPV, as stated in the World Health Organization guidelines.1 3 4 The guidelines give a central role to women-centred care in the implementation of a health-care response to IPV: the response should address the diverse needs that every specific woman might have and confidentiality, support and non-judgemental attitudes have to be ensured.4 However, the literature shows that encounters between women exposed to IPV and health-care providers are not always satisfactory,5 6 and a number of barriers that prevent individual health care providers from responding to IPV have been pointed out. These include organizational barriers, time constraints, an attitude of blaming vis-à-vis women exposed to IPV, lack of training, and lack of community resources to team up with, to cite just a few.7-9 In addition, there are strong inequalities in the response that women exposed to IPV receive from the health care professionals they meet, depending on the individual characteristics of the professional and/or the specific health care team they visit or are assigned to.8 10 Individual characteristics of health care professionals such as age, gender, training received, and attitudes towards IPV have been associated with the type and quality of response provided by health-care providers.7 9 11 12 Previous studies in Spain have pointed out that the combination of identified that team's self-efficacy, perceived preparation and the implementation of a woman-centred approach promotes better health care responses to women exposed to IPV.10 While a primary health care approach is perceived as facilitating more comprehensive responses to intimate partner violence, existing health system's structures are considered not conducive.13 Identifying and understanding promotive team level factors and dynamics seems essential in order to strengthen interventions aimed at implementing health-care actions to prevent and manage IPV.

This study analyses how team level conditions and strategies influence health care professionals’ responses to IPV.

Methods

Setting and case selection

We adopted a multiple, embedded case study design, since this design allows for an in-depth exploration of the interrelationship of context, processes and outcomes as they happen in their natural setting. One of the key advantages of the case study design is that it allows investigating a “phenomenon within its real-life context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident”.14 The case study design encourages the use of different sources of information and data collection methods, which strengthens a holistic approach. For these reasons, it is widely used in health systems research.15

In the case study design, the site selection is purposive: the cases should enable ‘testing’ of the hypothesis. It is often interesting to choose contrastive cases that present differences in contexts, intervention modalities or outcomes. We chose four primary care centers (PCCs): La Virgen, El Campo, Mora and Cristina, located in the south-eastern coast of Spain. Two of the cases were classified as “good” (La Virgen and El Campo) and two as “average” (Mora and Cristina) in relation to their responses to IPV. These four PCCs were first suggested by the persons in charge for coordinating the IPV response within the health system of this autonomous regions. Response to IPV of each of the PCCs was afterwards assessed using the Spanish version of the Physicians Readiness to Respond to IPV questionnaire (PREMIS), focusing on the items that refer to practice issues. More details of the Spanish version of the questionnaire can be found in Vives Cases et al.16 Professionals working in the two cases classified as “good” scored significantly higher in practice issues than the two cases defined as “average”, adjusting for age, sex/gender, professional background and years of experience (more details on the sample and results can be found in Appendix A).

Total scores for practice issues, as well as other characteristics of each case can be found in Appendix A while more details on the methods for data collection and sample can be found in Appendix A.

Data collection

Quantitative and qualitative data were collected from each case between January and September 2013 by IG and EB (Appendix A).

In each case, a social network analysis questionnaire was administered to all health care professionals who accepted to participate.17 18 The SNA questionnaire investigated the relationship between the team members in regard to IPV consultations. SNA measures interactions between pairs of actors and uses these data to map the structure of relations and collaboration in a whole network. It has been used to measure the degree of collaboration and mutual support in networks.17-19 In this study, each member of the team -our network under study- was asked to identify every other member with whom s/he consulted when facing a case of IPV. Ninety-three professionals filled in the SNA questionnaire.

Qualitative data were collected through semi-structured individual interviews with GPs, nurses, midwifes, social workers and other health care professionals working in each of the PCCs (a total of 44) (Appendix A). Issues included in the interviews guide are further described in Appendix A. The interviews were made by two of the authors (EB, IG) and digitally recorded after written consent was granted. The duration of the interviews ranged from 15minutes to more than one hour. Observations were conducted in waiting areas and during consultations and meetings. Interaction between users and professionals and between the team members was observed and reported in written notes.

Data analysis

Responses to the SNA questionnaire were tabulated and entered in a matrix. The software UCINET was used in producing the graphics. The number of relational ties and the density of the network for each case were calculated. Density indicates the degree of cohesion of a network with values closer to 1 showing higher cohesion. Network centralization was also calculated; the extent to which a network is dominated by a single (or few) central node, with values ranging from 0 to 1.20

Qualitative interviews were transcribed verbatim and analyzed using thematic analysis, along with notes taken during observations.21 The coding process was done manually. First, we read the interviews several times to identify emerging topics of interest, which were used as predefined codes. We identified the parts of the transcripts referring to those codes, while at the same time remaining open to new emerging codes. Next, the preliminary codes were refined, expanded and finally aggregated to develop themes.

Results

Dynamics and structures that promote team working and team learning on IPV

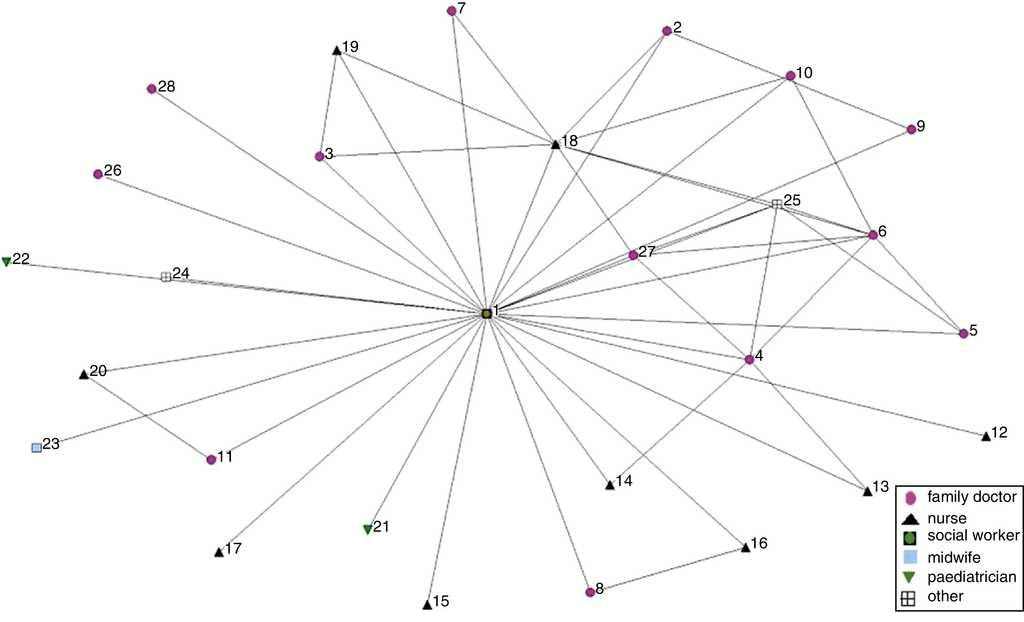

The results of the SNA showed that the networks of La Virgen and El Campo had the highest density scores (Table 1 and Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4), namely when cases of IPV were seen by health care professionals in La Virgen and El Campo, more consultations with other health care professionals in the team took place than in Cristina and Mora.

Table 1 Number of relational ties, density and centralization of the networks in each of the PHC teams.

| N relational ties | Density | Centralization | |

|---|---|---|---|

| La Virgen | 100 | 0,132 | 0,935 |

| El Campo | 40 | 0,19 | 0,9341 |

| Mora | 52 | 0,094 | 0,514 |

| Cristina | 36 | 0,055 | 0,46 |

The qualitative interviews and observations supported these findings. Especially in La Virgen, the motto was that IPV care should be provided in teams (Table 2).

Table 2 Themes and selected quotations.

| Theme | Selected quotations |

|---|---|

| Dynamics and structures that promote team working and team learning on IPV | We always say that any woman exposed to IPV, is not the responsibility of one provider of the team. She is my patient, but she is also known by her nurse, by the social worker… She will be a patient who receives a coordinated support from the team. (Family doctor 1, La Virgen) Team meetings are opportunities that I always use to tell the other professionals: “If you see a case of IPV you can come and talk to me, you can refer the woman to me or we can work together…”. I can give some suggestions and we can share the burden, the anxiety (Social worker, El Campo) I have been working in this team six years and I can tell you that we have never talked about IPV in any of our weekly meetings. (Medical coordinator, Mora) |

| Committed social workers in an enabling environment | I myself am the same person in El Campo and Zarzas [the two health care centers she works with] … The team in El Campo has a tradition of working for maybe more than 20 years with a psychosocial approach, as a multidisciplinary team, with a social worker… The team in Zarzas they have had a social worker for maybe what? six years? … Besides, Zarzas is located close to the capital, and a lot of doctors who are about to retire, they want to come there…, and they come from the ‘old school’ with a biomedical working style […]. They underestimate the value of psychosocial approaches […] In addition, the relationships between the professionals are not that good. The medical coordinator has failed to promote team work. We do not have team meetings [in Zarzas]. (Social worker, El Campo). |

| Explicit strategies to implement a women-centred approach | [When asked how did she detect IPV cases] Usually, I notice that this woman starts coming frequently when she seldom came previously, or that she starts complaining about different issues …., what we call the malaise syndrome… That's how I have detected IPV cases. I mean, there are women who are almost imploring you to ask them… (Family doctor 2, El Campo) When the aim and care focuses on the woman, then […] establishing a trust relationship will be more important than any other issue, more important than filling a report, the protocol, the bruise… This approach will help me to make appropriate decisions. (Social worker, El Campo) We ask [about IPV] when we see injuries. […] But as a routine, we don’t ask anything. […] When there is objective maltreatment, then there will be a denouncement. Sometimes, we insist that they have to fill a denouncement form immediately (Family doctor 3, Cristina) Now that we have the women's group there are issues that we can handle here in the health care center. In the group, women work out issues that are different from the ones that can be dealt with in individual consultations. (Family doctor 4, La Virgen). |

In La Virgen and El Campo, the teams developed spaces for promoting team learning on IPV. In these spaces through exchange and support, less knowledgeable health care professionals gained new knowledge on IPV, and they felt more secure and supported when they had doubts (Table 2).

Team learning on IPV did not happen in the other two cases where IPV has never been discussed during regular team meetings (Table 2).

Committed social workers in an enabling environment

We found that social workers are key professionals for dealing with IPV in all the four teams. The SNA graphs show that in La Virgen and El Campo, and to a lesser extent in Mora, the networks are centralized around the social workers. The high centralization scores in La Virgen (0.94) and El Campo (0.93) point out the key role of the social worker in supporting the response to women exposed to IPV. The lower centralization scores in the other two cases indicate that the mere existence of a social worker in the team is not enough to promote consultations on IPV (Table 2 and Figures 1 to 4).

The qualitative analysis showed that among teams with a social worker who was motivated, interested and knowledgeable on IPV, it was easier to generate interest on IPV among the other professionals. The qualitative analysis also pointed out that even the most committed and knowledgeable social worker might not be able to enhance team work if s/he is the only one interested and/or if s/he is part of a disorganized team, as the social worker from El Campo explained (Table 2).

Explicit strategies to implement a women-centred approach

The two “good” teams were actively engaged in implementing what they called “the women malaise approach”. The women's malaise approach considers that somatic symptoms with no identifiable organic cause are related to contextual, subjective and sex/gender-related factors, and that a purely biomedical approach to health therefore cannot adequately address such symptoms.22 23 The interviewees considered that this approach changed the way they approach women during consultations. They considered it key to improve detection of IPV and, most importantly, to centre the response to IPV on the woman (Table 2).

This is in contrast with the other two cases, where the response focused more on filling legal reports and convincing women to denounce the perpetrator than on caring for the woman herself (Table 2).

The women malaise approach has influenced how the professionals approach their women patients: from a gender perspective, taking a holistic approach, trying to connect unspecific complains with social circumstances and not only focusing on prescribing drug to address symptoms. This approach also inspired concrete actions beyond the clinical setting, like the organization of therapeutic women's groups: groups of women who gathered weekly with trained professionals from the team to engage in talk therapy and other activities (i.e. therapeutic massage). The existence of the ‘women group’ in La Virgen and El Campo expanded the options of the team members beyond merely referring to the social worker and issuing legal reports. As a result, the ‘women group’ made professionals feel less frustrated as they could offer the women some valuable extra options (Table 2).

The professionals’ meetings previously described also served as spaces for exchange and support professionals in implementing such approach.

Discussion

This study shows that the conditions of the team affect the way individual health care providers respond to women exposed to IPV. Health care professionals respond better to women exposed to IPV when they work in teams: 1) that facilitate staff to talk and discuss about IPV in their meetings; 2) where members consult each other when faced with IPV cases; 3) with knowledgeable and motivated social workers; 4) with an enabling team climate; and 5) that implement concrete strategies for women-centred care.

SNA studies have showed that denser networks favour the diffusion of changes, especially when the adoption of the new behaviour requires social reinforcement.24 This seems to be the case for IPV response within primary care teams, since we found that in the teams with denser networks, health care professionals were responding better to women exposed to IPV. However, we have acknowledge that none of the networks showed a very high density, which might reflect that IPV is yet to become a health issue in which health care professionals routinely consult and collaborate with others.8 It might also reflect that despite the expectation that Spanish primary care centers work as multidisciplinary teams, this is hindered by work pressure and the lack of concrete strategies or guidelines to do so.13 25

Team structure, processes and climate have an impact on interdisciplinary team working; the importance of ensuring regular team meetings and the availability of organizational support to foster interdisciplinary team work in primary care that emerged from this study has been reported elsewhere, although not in relation with IPV.26 27 Team-based responses to IPV contribute to health care professionals remaining updated by providing spaces to learning from exchange with each other, and to share the burden, in terms of work load but also emotional pressure. More importantly, they allow for a more comprehensive response to IPV in which professionals from different sectors and with different expertise are involved. The importance of an interdisciplinary response to IPV has also been acknowledged in the WHO guidelines and in the literature.1 4

This study shows that social workers play a key role when it comes to IPV. This is not surprising, given that they are recognized as the experts on this and other “social” issues within primary care teams, both by the rest of the health care providers as well as by policies and guidelines. We also showed, however, that having a social worker within the team is not enough to foster a team-based response to IPV. In order to foster change, social workers have to be “champions”, namely “identified with the idea as their own, and with its promotion as a cause, to a degree that goes far beyond the requirements of their job”.28 The key role of organizational champions in promoting change within local contexts has been highlighted in the literature.28-30 While champions may play an important role at the inception stage (as arguably is the case in our study), at latter stages the development of a “critical mass” is necessary.30 In that sense, the fact that the network in La Virgen shows a certain degree of centralization around other actors beyond the social worker, might point out a more advanced stage in the implementation of a team-based response to IPV in this center.

The results of our study are in line with other studies that highlight the key role of organizational factors in shaping individual health care providers’ responses to different health issues, in this case to IPV. Teams that have a good climate and horizontal leadership that allows freedom to health care professionals to innovate stimulate individuals to adopt innovations.29 31

Finally, this study underlines the relevance of a women-centred approach for facilitating health care responses to IPV, and the importance of developing concrete strategies for the implementation of such approach. The literature shows that the implementation of women-centred care for different health issues (i.e. childbirth, cardiovascular disease, drug abuse, and reproductive health) improves women's satisfaction and utilization of services, and that it may improve certain health outcomes -although there are some contrasting results.32-34 However, to our knowledge, there are no studies that explored how and why women-centred care can contribute to better health-care responses to IPV. Despite inclusion of women-centred care as a key strategy for responding to women exposed to IPV within health services in the WHO guidelines, there is no explicit guidance in how such approach can be implemented.4 This is a critical issue, since the main barrier for implementing women-centred approaches might not be that health care professionals do not consider it important, but that routine care processes discourage providers to practice women-centred care consistently, as has been also found for person-centred care.35

Our findings point out two concrete actions that can support health care professionals to implemented women-centred care in general and specifically for dealing with women exposed to IPV. First, meetings to discuss cases can serve as spaces to learn, share and debrief, and help teams and individual health care professionals to improve how they implement a women-centred care in their consultations. Second, the women's therapeutic groups serve four goals. They constitute a complementary way to respond to women's needs, serve as well as a backup for professionals beyond their consultations, provide a way of identification, and remind professionals of how care should be delivered within the team. It is encouraging to point out that some autonomous regions are already implementing similar groups within primary health care and/or other socio-sanitary services.36 37 It is important to notice that implementing women-centred care demands professionals to incorporate a gender perspective to health and health-care which is still far from being mainstreamed in health care systems.

While the design of the study allows us to see that there are connections between team level conditions and processes on one hand, and individual readiness to respond to IPV, there are some limitations. Due to the design, we cannot demonstrate a cause-effect relationship. In addition, we focus here in team level factors, while there could be contextual factors beyond the team that could have influenced the responses. We could only carry out an in-depth analysis of four cases. It would have been interesting to explore more contrasting cases (i.e. teams that were not implementing the women malaise approach but where health care providers scored high for readiness to respond to IPV). We rely on the PREMIS scores for practices to qualify health care professionals’ responses to IPV; since these scores are calculated from professionals’ own self reporting, it can be questionable whether the scores accurately reflect the quality of the IPV response. In addition, in this study the PREMIS was applied not only to physicians −the original target group of the instrument− but also to other health care professionals; some of the questions might not be equally relevant for non-physicians.

Conclusions

Team level strategies and processes influence how health care professionals respond to women exposed to IPV. Better individual readiness to detect and respond to IPV and a more comprehensive response to women exposed to IPV are implemented in teams which: 1) have social workers knowledgeable on IPV and motivated to engage others; 2) develop and sustain a structure of regular meetings during which issues of IPV are discussed; 3) stimulate a friendly team climate; and 4) implement concrete actions towards women-centred care.

What is known about the topic?

Primary health care teams can play an important role in responding to women exposed to intimate partner violence, but there is huge heterogeneity in regard to how each team and each professional responds and little is known about how team factors influence such responses.

What does this study add to the literature?

To respond better to intimate partner violence primary health care teams should: 1) integrate social workers who are knowledgeable and motivated to engage others; 2) sustain a structure of regular meetings during which issues of violence are discussed; 3) stimulate a friendly climate and a leadership that promotes individual innovation; and 4) implement concrete actions towards women-centred care.