Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD), which includes hypertension and cardiac ischemic conditions, among other1 is currently one of the most prevalent non-communicable diseases2, affecting up to 57% of the global population3. It is considered by the World Health Organization as one of the major causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide4, and is currently responsible for causing 32% of deaths in the world3.

CVD risk factors can be either modifiable, which include tobacco consumption, obesity, a sedentary life, a high-fat diet, and high blood pressure, and non-modifiable, such as age or sex5) In general, the population presents several of these factors that usually interact with each other, and thus enhance their individual effects6.

It has been reported that teachers may have an increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease, due to their sedentary lifestyle7, the constant changes in their workplace and the limited free time they have. All of this could lead to a poor diet and thus have a negative impact on their cardiovascular health8,9.

Taking this into consideration, the aim of this study was to identify the cardiovascular risk factors associated to teaching staff and determine their cardiovascular risk, which could serve as a basis for subsequent preventive actions in the workplace.

Methods

A retrospective and cross-sectional study was carried out in a group of 4.738 teachers from different Spanish geographic areas between January 2019 and July 2020. Teachers were selected from among those who went to periodic occupational health medical examinations considering the following inclusion criteria:

Aged between 18-67 years.

Be actively working.

Accepted their voluntary participation in the study and authorized the use of data for epidemiological purposes.

No previous serious CVD (myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular disease, etc.)

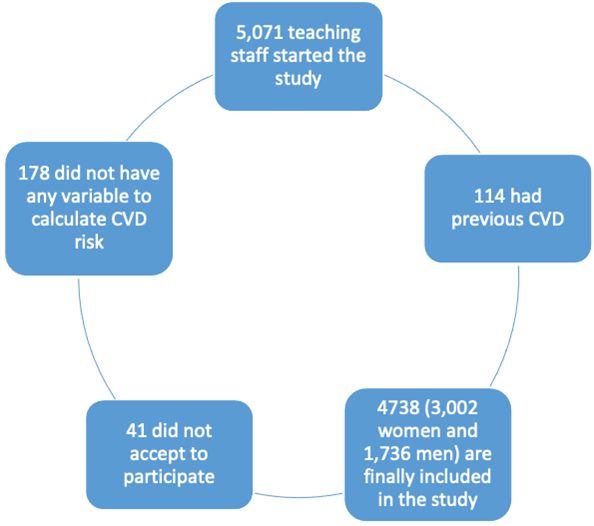

Figure 1 is a representative depiction of how participants were included in the study.

Anthropometric, clinical and analytical measurements were carried out by the health personnel of the different occupational health units participating in the study, after homogenizing the measurement techniques.

Parameters related to CVD risk included in the assessment

Weight (expressed in kg) and height (expressed in cm) were determined with a scale-height rod using a SECA 700 (with a 200 kg capacity and divisions of 50 grams) and a SECA telescopic height rod 220 with millimeter division and 60-200 cm intervals.

Abdominal waist circumference was measured in cm with a SECA 200 tape measure, with an interval of 1-200 cm and millimeter division. For measurement, the person stood upright, feet together, abdomen relaxed and upper extremities hanging on both sides of the body. The tape measure was then placed at the level of the last floating rib, parallel to the ground. The waist/height ratio (WtHR) was calculated by dividing the waist circumference by the height, and was considered high when WtHR> 0.50.

Blood pressure was measured in the supine position with a calibrated OMRON M3 automatic sphygmomanometer and after 10 minutes of rest. Three determinations were made at one minute intervals, obtaining the mean value of the three. Values >140 mm Hg systolic or >90 mm Hg diastolic were considered hypertension. Blood tests were obtained by peripheral venipuncture after a 12h fast and were processed in a maximum time of 48-72h.

Automated enzymatic methods were used for blood glucose, total cholesterol and triglycerides determination. Values are expressed in mg/dl. HDL (mg/dl) was determined by precipitation with MgCl2 dextran sulfate, and LDL (mg/dl) was calculated using the Friedewald formula (provided that triglycerides were <400 mg/dl).

Friedewald formula: LDL=total cholesterol-HDL-triglycerides/5

Basal blood glucose results were classified based on the recommendations of the American Diabetes Association10, considering hyperglycemia >125 mg/dl. Lipid profile values were classified according to the recommendations of the Spanish Heart Foundation (high cholesterol >239 mg/dl, high LDL >159 mg/dl, and high triglycerides >200 mg/dl).

Three atherogenic indexes were calculated:

Cholesterol/HDL (considered high when >5 in men and >4.5 in women)

LDL/HDL (high values >3)

Triglycerides/HDL (high values >3)11

Metabolic syndrome was determined using three models:

a) NCEP ATP III (National Cholesterol Educational Program Adult Treatment Panel III), which establishes metabolic syndrome when three or more of the following factors are present: waist circumference is greater than 88 cm in women and 102 in men; triglycerides >150 mg/dl or specific treatment is followed; blood pressure >130/85 mm Hg; HDL <40 mg/dl in women or <50 mg/dl in men or specific treatment is followed; and fasting blood glucose >100 mg/dl or specific glycemic treatment is followed.

b) The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) model12, which considers the presence of central obesity necessary, defined as a waist circumference of >80 cm in women and >94 cm in men, in addition to two of the other factors abovementioned for ATP III (triglycerides, HDL, blood pressure and glycaemia).

c) The JIS model13, which follows the same criteria as NCEP ATPIII but the waist circumference cut-off values are 80 cm in women and 94 cm in men.

The REGICOR scale, which is an adaptation of the Framingham scale to the characteristics of the Spanish population14, estimates the risk of suffering a cerebrovascular event in a period of 10 years. This scale can be applied to people between 35 and 74 years old, where the risk is moderate at >5% and high at >10%15. The SCORE scale recommended for Spain16,17 estimates the risk of suffering a fatal cerebrovascular event in a period of 10 years. It applies to people between 40 and 65 years old, and the risk is considered moderate at >4% and high at> 5%16. In order to determine vascular age, calibrated tables were used18. For vascular age using the Framingham model18, age, gender, HDL-c, total cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, hypertensive treatment, tobacco consumption and diabetes are all taken into consideration and can be used in individuals of >30 years of age. For vascular age using the SCORE model19, age, gender, systolic blood pressure, tobacco consumption and total cholesterol are considered and can be used in individuals aged between 40 and 65 years old. An interesting concept that can be applied to the vascular ages using both these models is the ALLY (avoidable lost life years)20, which can be defined as the difference between the biological age (BA) and vascular age (VA).

ALLY = VA - BA

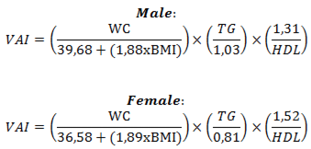

To calculate the visceral adiposity index21) (VAI), the following formula was used:

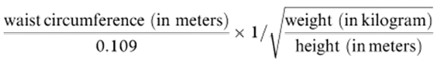

The Conicity index22 was calculated using the following formula:

The cardiometabolic index (CMI)23 was calculated by multiplying the waist-to-height ratio times the atherogenic triglycerides index/HDL-c.

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight by height in squared meters. Obesity was considered over 30. The waist-to-height ratio was considered to be of risk when >0.5024.

We used two formulas to estimate the percentage of body fat:

Relative fat mass (RFM)25, whereby the height and waist circumference are expressed in meters.

Women: 76- (20 x (height/waist))

Men: 64- (20 x (height/waist))

The cut-off points for obesity were 33.9% in women and 22.8% in men.

CUN BAE26 (University of Navarra Body Adiposity Estimator Clinic) using the following formula:

44.988 + (0.503 x age) + (10.689 x sex) + (3.172 x BMI) - (0.026 x BMI2) + (0.181 x BMI x sex) - (0.02 x BMI x age) - (0.005 x BMI 2x sex) + (0.00021 x BMI2 x age)

Where male gender is equal to 0 and female equal to 1.

The CUN BAE cut-off points for obesity are 25% in men and 35% in women.

The fatty liver index (FLI)27 determines the risk of suffering from non-alcoholic fatty liver and is calculated as follows:

FLI = (e0.953*log e (triglycerides) + 0.139*BMI + 0.718*log e (ggt) + 0.053*waist circumference - 15.745) / (1 + e0.953*log e (triglycerides) + 0.139*BMI + 0.718*log e (ggt) + 0.053*waist circumference - 15.745) x 100

FLI scores of 60 and above indicated that FL was present.

Lipid accumulation product (LAP)28 was calculated using the following formula:

In men: (waist circumference (cm) - 65) x (triglyceride concentration (mMol)).

In women: (waist circumference (cm) - 58) x (triglyceride concentration (mMol))

TyGindex29 = LN (triglycerides [mg/dl] × glycaemia [mg/dl]/2).

Atherogenic dyslipidemia (AD) is characterized by high values of triglycerides (>150 mg/dl), low levels of HDL (<40 mg/dl in men and <50 mg/dl in women) and normal or slightly high levels of LDL. If these latter ones are also high, it is known as the lipid triad (LT)30.

An individual was considered a smoker if they had regularly consumed at least 1 cigarette/day (or the equivalent in other types of consumption) in the last month, or had stopped smoking less than a year ago.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive analysis of the categorical variables was carried out, calculating the frequency and distribution of responses for each of them. For quantitative variables, the mean and standard deviation were calculated, and for qualitative variables the percentage was calculated. A bivariate association analysis was performed using the c2 test (with a correction with the Fisher’s exact statistical test, when conditions required so) and a Student’s t-test for independent samples. For the multivariate analysis, binary logistic regression was used with the Wald method, with an Odds-ratio calculation and a Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. Statistical analysis was performed with the SPSS 27.0 program and a p value of <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Ethical considerations and aspects

The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Health Area of Illes Balears in November 2020. All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki. All patients signed written informed consent documents prior to participation in the study.

Results

The descriptive analysis indicates that the sample population included is predominantly made up of women between 40-41 years old. All analyzed variables presented less favorable values in men, except the amount of smokers, which was higher in women. Thus, differences between are statistically significant for all variables, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: Characteristics of teaching staff.

| Women n=3002 | Men n=1736 | Total n=4738 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean (sd) | mean (sd) | mean (sd) | p-value | |

| Age | 40.8 (10.6) | 41.4 (10.0) | 41.0 (10.4) | 0.057 |

| Height | 162.8 (6.3) | 176.1 (6.8) | 167.7 (9.1) | <0.0001 |

| Weight | 65.0 (12.7) | 81.0 (13.0) | 70.9 (15.0) | <0.0001 |

| Waist | 73.7 (9.6) | 85.0 (10.2) | 77.8 (11.2) | <0.0001 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 116.8 (14.4) | 126.2 (14.7) | 120.2 (15.2) | <0.0001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 71.5 (10.5) | 77.1 (10.4) | 73.5 (10.8) | <0.0001 |

| Total cholesterol | 194.4 (35.6) | 196.0 (35.9) | 195 (35.7) | <0.0001 |

| HDL-c | 56.8 (8.2) | 50.9 (7.8) | 54.6 (8.6) | <0.0001 |

| LDL-c | 120.0 (34.6) | 122.3 (34.6) | 120.8 (34.6) | <0.0001 |

| Triglycerides | 88.1 (48.3) | 115.8 (70.3) | 98.3 (58.9) | <0.0001 |

| Glucose | 87.1 (14.7) | 92.9 (24.5) | 89.2 (19.1) | <0.0001 |

| AST | 19.1 (8.4) | 22.5 (6.8) | 20.4 (8.0) | <0.0001 |

| ALT | 20.9 (15.6) | 30.5 (23.8) | 24.6 (19.8) | <0.0001 |

| GGT | 20.3 (16.0) | 33.9 (30.5) | 25.5 (23.6) | <0.0001 |

| Percentage | Percentage | Percentage | p-value | |

| <30 years | 16.1 | 12.7 | 14.8 | <0.0001 |

| 30-39 years | 32.5 | 32.0 | 32.4 | |

| 40-49 years | 28.0 | 32.0 | 29.5 | |

| ≥50 years | 23.4 | 23.3 | 23.3 | |

| Smokers | 66.8 | 68.1 | 67.2 | <0.0001 |

| Non-smokers | 33.2 | 31.9 | 32.8 |

The average values obtained using the different scales and scores present more unfavorable values in men, including those associated to overweight and obesity (BMI, WtHR, CUN BAE, RFM, VAI and CI), cardiovascular risk (ALLY vascular age, REGIOR scale and SCORE scale), fatty liver indexes (FLI, LAP), and atherogenic indexes (metabolic syndrome and CMI). All data are presented in Table 2.

Regarding the prevalence of altered values of the different scales, women are those who present a more favorable result, whereby they were all statistically significant different compared to men (Table 3).

Regarding the multivariate analysis using logistic regression, the only parameter that had any influence in all the analyzed scales was age, with ORs ranging from 1.7 ((95 CI 1.3-2.1) for WtHR > 0.50 to 184.7 (95% CI 61.9-551.4) for SCORE scale moderate-high. On the contrary, tobacco consumption only had an influence on the REGICOR and SCORE scales (Table 4).

Table 2: Mean values of the different CVR scales according to gender in teaching staff.

| Women n=3002 | Men n=1736 | Total n=4738 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean (sd) | mean (sd) | mean (sd) | p-value | |

| Body mass index | 24,5 (4,7) | 26,1 (3,9) | 25,1 (4,5) | <0.0001 |

| Waist-to-height ratio | 0.45 (0.06) | 0.48 (0.06) | 0.046 (0.06) | <0.0001 |

| CUN BAE* | 34.4 (6.5) | 24.9 (5.7) | 30.9 (7.7) | <0.0001 |

| Relative fat mass | 31.1 (5.3) | 22.1 (4.6) | 27.8 (6.7) | <0.0001 |

| Visceral adiposity index | 2.7 (1.7) | 6.8 (5.9) | 4.2 (4.3) | <0.0001 |

| Conicity index | 1.1 (0.1) | 1.2 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.1) | <0.0001 |

| ALLY SCORE vascular age | 4.0 (4.8) | 7.1 (6.5) | 5.2 (5.7) | <0.0001 |

| ALLY Framingham vascular age | 0.1 (10.9) | 5.1 (9.5) | 1.9 (10.7) | <0.0001 |

| SCORE scale | 0.5 (0.9) | 1.6 (2.2) | 0.9 (1.6) | <0.0001 |

| REGICOR scale | 2.3 (1.8) | 3.1 (2.2) | 2.6 (2.0) | <0.0001 |

| Fatty liver index | 15.5 (19.6) | 33.6 (25.8) | 22.4 (23.9) | <0.0001 |

| Lipid accumulation product | 16.8 (16.9) | 28.5 (29.4) | 21.1 (23.0) | <0.0001 |

| AI Cholesterol/HDL-c | 3.5 (0.9) | 4.0 (1.1) | 3.7 (1.0) | <0.0001 |

| AI Triglycerides/HDL-c | 1.6 (1.0) | 2.4 (1.9) | 1.9 (1.4) | <0.0001 |

| AI LDL-c/HDL-c | 2.2 (0.8) | 2.5 (0.9) | 2.3 (0.8) | <0.0001 |

| Cardiometabolic index | 0.7 (0.5) | 1.2 (1.1) | 0.9 (0.8) | <0.0001 |

| Nº factors metabolic syndrome NCEP ATPIII criteria | 0.8 (1.0) | 1.1 (1.2) | 0.9 (1.1) | <0.0001 |

| Nº factors metabolic syndrome JIS criteria | 0.8 (1.1) | 1.5 (1.3) | 1.1 (1.2) | <0.0001 |

| Triglyceride-glucose index | 8.1 (0.5) | 8.4 (0.6) | 8.3 (0.5) | <0.0001 |

(*) CUN BAE Clínica Universitaria de Navarra Body Adiposity Estimator.

Table 3: Prevalence of altered values of the different CVR scales by gender in teaching staff.

| Women n=3002 | Men n=1736 | Total n=4738 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | p-value | |

| Waist to height ratio >0,5 | 16.1 | 33.5 | 22.5 | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 10.9 | 23.6 | 15.5 | <0.0001 |

| Total Cholesterol ≥200 | 39.9 | 42.9 | 41.0 | <0.0001 |

| LDL-c ≥130 | 36.0 | 38.9 | 37.1 | <0.0001 |

| Triglyceride ≥150 | 6.9 | 21.1 | 12.1 | <0.0001 |

| Glucose ≥100 | 10.5 | 22.6 | 14.9 | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes | 1.0 | 2.6 | 1.6 | <0.0001 |

| SCORE scale moderate-high* | 3.7 | 23.8 | 11.4 | <0.0001 |

| REGICOR scale moderate-high** | 12.4 | 18.0 | 14.5 | <0.0001 |

| Not metabolically healthy | 47.6 | 65,0 | 53.9 | <0.0001 |

| Metabolic syndrome NCEP ATPIII | 7.0 | 12.9 | 9.2 | <0.0001 |

| Metabolic syndrome IDF | 7.5 | 8.6 | 7.9 | <0.0001 |

| Metabolic syndrome JIS | 8.5 | 21.4 | 13.2 | <0.0001 |

| Atherogenic dyslipidemia | 3.5 | 7.7 | 5.0 | <0.0001 |

| Lipid triad | 0.9 | 2.1 | 1.4 | <0.0001 |

| Total Cholesterol/HDL-c moderate-high | 12.4 | 15.0 | 13.3 | <0.0001 |

| Triglyceride/HDL-c high | 5.6 | 22.4 | 11.7 | <0.0001 |

| LDL-c/HDL-c high | 14.3 | 25.5 | 18.4 | <0.0001 |

| Obesity body mass index | 11.7 | 15.0 | 12.9 | <0.0001 |

| Obesity CUN BAE | 42.6 | 43.9 | 43.1 | <0.0001 |

| Obesity relative fat mass | 29.4 | 44.0 | 34.8 | <0.0001 |

| Fatty liver index high risk | 6.1 | 19.7 | 11.3 | <0.0001 |

(*) women n= 1532 men n=958 total n=2490 (**) women n= 2046 men n=1222 total n=3268

Table 4: Logistic regression analysis.

| Gender | Age | Tobacco | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | CI 95% | p | OR | CI 95% | p | OR | CI 95% | p | |

| Waist to height ratio >0,5 | 2.7 | 2.2-3.2 | <0.0001 | 1.7 | 1.3-2.1 | <0.0001 | ns | ||

| Hypertension | 2.7 | 2.1-3.4 | <0.0001 | 3.4 | 2.7-4.4 | <0.0001 | ns | ||

| Total Cholesterol ≥200 | ns | 3.9 | 3.2-4.8 | <0.0001 | ns | ||||

| LDL-c ≥130 | ns | 4.1 | 3.4-5.0 | <0.0001 | ns | ||||

| Triglyceride ≥150 | 3.7 | 2.9-4.8 | <0.0001 | 2.1 | 1.6-2.8 | <0.0001 | ns | ||

| Glucose ≥100 | 2.6 | 2.1-3.3 | <0.0001 | 3.6 | 2.8-4.5 | <0.0001 | ns | ||

| Diabetes | 2.7 | 1.4-5.2 | 0.002 | 2.7 | 1.4-5.2 | 0.003 | ns | ||

| SCORE scale moderate-high | 26.5 | 14.4-48.8 | <0.0001 | 184.7 | 61.9-551.4 | <0.0001 | 10.6 | 5.9-19.3 | <0.0001 |

| REGICOR scale moderate-high | 1.9 | 1.4-2.6 | <0.0001 | 25.1 | 16.5-38.1 | <0.0001 | 2.6 | 1.9-3.7 | <0.0001 |

| Not metabolically healthy | 2.1 | 1.8-2.6 | <0.0001 | 3.8 | 3.1-4.7 | <0.0001 | ns | ||

| Metabolic syndrome NCEP ATPIII | 2.0 | 1.5-2.7 | <0.0001 | 3.7 | 2.8-4.9 | <0.0001 | ns | ||

| Metabolic syndrome IDF | ns | 2.2 | 1.6-3.0 | <0.0001 | ns | ||||

| Metabolic syndrome JIS | 3.1 | 2.4-4.0 | <0.0001 | 3.2 | 2.5-4.1 | <0.0001 | ns | ||

| Atherogenic dyslipidemia | 2.4 | 1.6-3.5 | <0.0001 | 3.2 | 2.2-4.6 | <0.0001 | ns | ||

| Lipid triad | 2.3 | 1.1-4.6 | <0.0001 | 6.5 | 3.1-13.6 | <0.0001 | ns | ||

| Cholesterol/HDL-c high | ns | 4.2 | 3.3-5.4 | <0.0001 | ns | ||||

| Triglyceride/HDL-c high | 5.1 | 3.8-6.7 | <0.0001 | 2.6 | 2.0-3.5 | <0.0001 | ns | ||

| LDL-c/HDL-c high | 2.2 | 1.8-2.7 | <0.0001 | 3.6 | 2.9-4.5 | <0.0001 | ns | ||

| Obesity body mass index | 1.3 | 1.0-1.7 | <0.0001 | 2.0 | 1.5-2.5 | <0.0001 | ns | ||

| Obesity CUN BAE | ns | 3.7 | 3.0-4.5 | <0.0001 | ns | ||||

| Obesity relative fat mass | 1.9 | 1.6-2.3 | <0.0001 | 1.6 | 1.3-1.9 | <0.0001 | ns | ||

| Fatty liver index high risk | 3.8 | 2.8-5.3 | <0.0001 | 2.0 | 1.5-2.8 | <0.0001 | ns | ||

Discussion

In terms of cardiovascular risk, teaching staff have been included in very few studies regarding primary prevention and health promotion plans. However, there are studies prior to ours that focus on the most common risk factors (smoking, exercise and dietary fat consumption), which offer the possibility of detecting CVD risk factors and the impact of CVD screening on the perception cardiovascular risk in teaching staff, as well as their role in health promotion. In this sense, data suggest that the detection and counselling regarding CVD risk factors is an effective strategy to positively influence the level of physical activity of teachers, and highlights their role as motivators-educators which could ultimately have benefits beyond the classroom31.

The results of our study show a more unfavorable situation for men than for women in terms of cardiovascular risk, presenting an increase in all studied factors except for tobacco consumption, which was higher in women. Furthermore, obesity and overweight both stand out as important risk factor. Previous studies carried out in Spain have highlighted the importance of BMI as a determining factor in overweight and obesity and consider it a constant variable that increases with age, as seen in this study also, and that confers a 6-times greater risk of CVD. However, this study32 does not show differences between men and women with statistical significance in BMI, probably due to the small sample size32. However, in Hispanic-American countries, taking as a reference the study carried out in teachers from the University of Peru, there seem to be differences between men and women, whereby women present more unfavorable results in terms of weight. This study advocates for the promotion of a healthy lifestyle, mainly by means of a healthy diet and an increase in physical activity, in order to reduce cardiovascular and metabolic risk33. Similar results have been obtained in other universities in Colombia34, Ecuador35 and Mexico36, although all of them present lower sample sizes than in our study and thus make comparisons difficult. However, independently of the differences between the sample sizes, all studies show that early intervention of modifiable risk factors is crucial, whereby changes towards a healthy lifestyle can be very effective.

Teaching staff rarely identify the difference between modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors, hence most go unnoticed by these individuals and occur repeatedly. Thus, it is necessary to reinforce this information via education and medical check-ups. If identified and treated in time, the epidemiological morbidity would be reduced worldwide, and there would be a reduction in mortality due to CVD complications. Overall, this would provide a better quality of life and reduce associated side effects. The more risk factors an individual presents, the more chances they have to suffer CVD37.

The prevalence of CVD risk factors among the studied teaching staff requires the planning of short, medium and long term interventions that take into consideration all of the parts involved: education and health authorities, education institutions, and teaching staff and families which, altogether, can contribute to reduce the prevalence of CVD in the future. Teaching staff is no exception regarding CVD risk factors, which as seen here can be affected by a sedentary lifestyle and an unhealthy diet, which promote overweight and obesity.

Conclusion

The prevalence of CVD risk factors among the studied teaching staff requires the planning of short, medium and long term interventions that take into consideration all of the parts involved: education and health authorities, education institutions, and teaching staff and families which, altogether, can contribute to reduce the prevalence of CVD in the future. Teaching staff is no exception regarding CVD risk factors, which as seen here can be affected by a sedentary lifestyle and an unhealthy diet, which promote overweight and obesity.