Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO  Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.96 no.8 Madrid ago. 2004

| ORIGINAL PAPERS |

Response of first attack of inflammatory bowel disease requiring hospital admission

to steroid therapy

M. Abu-Suboh Abadía, F. Casellas, J. Vilaseca and J-R. Malagelada

Service of Digestive Diseases. Hospital Universitari Vall d'Hebron. Barcelona. Spain

ABSTRACT

Introduction: corticoid administration is the usual treatment of Crohn' disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) attacks. How-ever, information available on response rates and their predictive factors is scarce.

Objective: to establish response to steroidal treatment in an homogeneous group of patients with CD or UC during their first admission to hospital.

Methods: restrospective analysis of 86 patients who received systemic steroidal treatment for a severe flare-up during their first hospital admission between 1995 and 2000. Patients were treated per protocol with fluid therapy, absolute diet, IV 6-methyl-prednisolone 1 mg/kg/day, and enoxaparin at prophylactic doses. Clinical response at 30 days was considered good in case of complete remission, and poor in case of partial or absent remission. Univariate and multivariate analyses according to non-parametric statistics were performed for sociodemographic and biologic variables.

Results: 45 patients with CD and 41 with UC were included. Good response rates were 64.4% for CD and 60.9% for UC. The univariate analysis showed that patients with good response have shorter evolution times and fewer previous flare-ups (p < 0.05) regarding CD. However, the multivariate analysis showed that none of the analyzed variables had predictive value.

Conclusion: the response rate of severe inflammatory bowel disease attacks to corticoids is around 60% in CD and UC. Data resulting from the current study cannot predict which patients will ultimately respond to therapy.

Key words: Inflammatory bowel disease. Ulcerative colitis. Crohn' disease. Severe relapse. Prognostic factors. Treatment. Corticosteroids.

Abu-Suboh Abadía M, Casellas F, Vilaseca J, Malagelada J-R. Response of first attack of inflammatory bowel disease requiring hospital admission to steroid therapy. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2004; 96: 539-547.

Recibido: 04-09-03.

Aceptado: 27-01-04.

Correspondencia: Francesc Casellas. Servicio de Digestivo. Hospital Universitari Vall d'Hebron, 119. 08035 BArcelona. e-mail: fcasellas@vhebron.net

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease includes a group of conditions with chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract of unknown etiology. It primarily consists of two diseases: ulcerative colitis (UC), in which inflammation involves the colon mucosa and submucosa, and Crohn' disease (CD), in which inflammation involves the whole wall and may affect any or all gastrointestinal segments. Both conditions are characterized by repeat, clinically active flare-ups alternating with varying periods of inactivity. The management of inflammatory bowel disease varies depending on its aim -the control of clinically active attacks or maintenance of remission. In order to keep remission various drugs may be used, including 5-amino salicylic (5-ASA) compounds and immunosuppressors such as azathioprine and 6-mercapto-purine (1). The standard treatment of moderate to severe flare-ups, both for CD and UC, includes oral or parenteral corticoid administration (2-5). Although the efficacy of corticoids may vary, cumulative experience and the absence of severe complications during acute use have kept them as the therapy of choice. Therapeutic alternatives in case of steroidal therapy failure include intravenous cyclosporine in severe refractory ulcerative colitis (6-8), methotrexate (9,10), and infliximab for CD (11).

Despite a wide acceptance of steroidal therapy in active inflammatory bowel disease, information is sparse on response rates, on factors that may predict them, and on whether outcome is changed on the long run. Since new treatments are increasingly available, which are more powerful though more expensive and with potentially more serious adverse effects, a recognition of factors -if any- allowing to predict response to steroid therapy for moderate to severe flare-ups would be most relevant, in order to identify which patients are eligible for other therapies as early as possible.

The goal of this study was to establish response rates to systemic corticoid therapy in a homogeneous group of inpatients with an initial severe attack of CD or UC both in the short and the long term.

METHODS

Patients

Patients requiring their first hospital admission for a severe attack of inflammatory bowel disease, either CD or UC, who received corticoids from 1995 to 2001 were included. Patients were diagnosed according to standardized clinical, endoscopic, radiographic and histological criteria (12). Activity extent was assessed using clinical indices. Clinical activity in patients with CD was assessed using Harvey-Bradshaw criteria (13), which refer to general condition, abdominal pain, number of daily stools, complications, and abdominal mass. Activity in patients with UC was assessed using Rachmilewitz criteria (14), which refer to number of weekly stools, blood in feces, general condition in the investigator' view, abdominal pain, fever, hemoglobin, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

Procedure

All patients in the study had been admitted to hospital and received treatment per protocol with absolute diet, total parenteral nutrition, i.v. methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg/day, and enoxaparin at prophylactic doses; they also underwent conventional clinical and laboratory monitoring. Response to corticoid therapy was assessed at 30 days after treatment onset by meeting the following criteria:

-Complete remission: complete regression of clinical symptoms; fewer than 2 daily stools, with no blood, pus or mucus in feces; no abdominal pain, and absence of fever, without weight loss or extraintestinal complaints.

-Partial remission: improvement from symptoms with fewer than 4 daily stools, with blood, pus or mucus in feces, abdominal pain but not daily, and no weight loss or extraintestinal complaints.

-No remission: unchanged or worsened clinical symptoms during follow-up (15,16).

-Response was considered good in case of complete remission, and poor in case of partial or no remission.

In order to establish factors predictive of good response, various social and demographic (age, gender, tobacco use, evolution time, and number of flare-ups), clinical (number of stools, blood in feces, fever, site, and activity index), and laboratory (leukocytes, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, hemoglobin, hematocrit, albumin, platelets, and fibrinogen) variables were collected at enrolment.

Patients who attained complete remission received maintenance therapy and a standardized corticoid-tapering regimen (weekly reduction of 10 mg down to 30 mg/day; hence weekly reduction of 5 mg to complete discontinuation); they were followed-up at outpatient clinics with clinical and laboratory monitoring every 6 months. Outcome was assessed during the following year, and the development of clinical activity evidence calling for therapy change was considered a new flare-up.

Statistics

Regarding the statistical analysis patients were divided up into two groups: ulcerative colitis and Crohn' disease, which were independently analyzed. Results were expressed as median and 25-75 percentile values. Statistical differences were first calculated by using a Mann-Whitney non-parametric univariate analysis or Fisher' exact test, when needed, and then a multivariate analysis.

RESULTS

Patients

Of 86 patients enrolled, 45 had CD and 41 had UC. Of 45 patients with CD, hospital admission was prompted by a first attack in 36, whereas the remaining 9 patients had already been diagnosed with CD during previous flare-ups, which had been exclusively managed on an outpatient basis. In the UC group, 35 were on their first attack and 6 were on a subsequent flare-up.

Short-term response to steroid therapy

At 30 days after treatment onset, 29 of 45 patients with CD had a good response, whereas the remaining 16 patients had a poor response (14 partial responses and 2 nil responses). The rate of good response to steroid therapy in the CD group was 64.4%.

Of 41 patients with UC, 25 had a good response and 16 had a poor response (10 partial responses and 6 nil responses) at 30 days after treatment onset; thus, the rate of good response in UC was 60.9%, not statistically different to that seen for CD.

Predictive factors for response

Table I includes all clinical, laboratory and sociodemographic data collected for patients with CD and UC at enrolment by response to steroid therapy.

For patients with CD, the univariate analysis showed that shorter evolution times and fewer previous flare-ups predicted a better response to corticoids (p < 0.05). In contrast, the univariate analysis showed no predictive variables regarding UC. A multivariate analysis of variables included in the univariate analysis showed that none of the analyzed variables (Table I) reached statistical significance in CD or UC.

Disease outcome in the long term

All 29 patients with CD who achieved complete remission by day 30 were followed up for one year. They received maintenance therapy with 5-ASA (22 patients) or azathioprine (4 patients), and 3 of them received no maintenance regimen. At one year, 16 patients (55%) were still in full clinical remission, 7 met steroid dependence criteria, and 6 had a new flare-up. Amongst the latter, 2 patients required surgery.

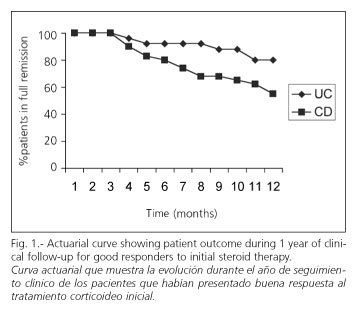

Furthermore, of 25 patients with UC who had a good response at day 30 during the study, 23 received maintenance therapy with 5-ASA, 1 with cyclosporine, and 1 received no maintenance treatment. At follow-up completion (one year) 20 (80%) were still in clinical remission and 5 (20%) had a new flare-up (Fig. 1). Amongst the latter, 1 required surgery (Fig. 2). The rate of new flare-ups during long-term follow-up was similar for CD and UC (55 vs 80%, respectively, p = ns).

DISCUSSION

This study assessed response to corticoids by first severe attacks of inflammatory bowel disease requiring hospital admission. After 30 days of standardized therapy with 1 mg/kg/day of parenteral 6-methyl-prednisolone a good response was achieved in 64.4% of patients with CD and 60.9% of patients with UC (p = ns). The rates of good response obtained by this study were similar to those reported elsewhere. Thus, Faubion, et al. (16) similarly established that full clinical response rates after 30 days of steroid therapy in 74 patients with active CD and 63 patients with active UC were 58% for CD and 54% for UC. In 1995, Kornbluth, et al. (17) published a meta-analysis that revealed mean remission rates of 62% (43-80%) for UC and 65% (55-94%) for CD.

Furthermore, sociodemographic and biologic variables able to predict good response to therapy have been researched. Our results suggest that shorter evolution times and fewer previous attacks predict a better response to steroids in CD (p < 0.05). However, the same analysis showed that no variable was of statistically significant predictive value for UC, even though a higher number of stools and a poorer clinical activity index score indicated a non-significant trend towards poorer response to therapy. This finding suggests that variables with significant predictive values could possibly be found with higher numbers of patients. The lack of predictive value of selected variables in our study confirms previous experiences with factors such as tobacco smoking (18).

The presence of predictive factors for good response to steroid therapy in inflammatory bowel disease attacks has been previously studied (19). In 1990, Malchow et al. showed that patients with CD exhibiting poorer response to treatment also had lower Crohn' Disease Activity Index (CDAI) scores, lower erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and longer disease when compared to those who responded (20). These findings could not be confirmed by Munkholm et al. (15) four years later, as they found no relationship between clinical symptoms (gender, abdominal pain, diarrhea, fever, and site of disease) or laboratory parameters (hemoglobin, leukocyte count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, serum albumin, and orosomucoid) and response to therapy in CD. On the other hand, Linsgren et al. identified as predictive factors for poorer response in UC the presence of fever, persistent diarrhea, and increased C-reactive protein on the third day of treatment (21). Travis et al. reported a good correlation between poorer response to steroids (defined as a need for colectomy in patients with UC) and more than 8 stools/day, or between C-reactive protein above 45 mg/L and 3 to 8 stools/day (22). Therefore, it may be safely affirmed that some agreement exists in that a greater number of stools, higher C-reactive protein levels, and decreased rates of serum albumin are all predictive factors for therapy failure in patients with severe active UC (19). However, no consensus exists on factors that may predict therapy failure in CD. Our study results provide no evidence supporting a predictive role of clinical variables for response to steroid therapy in inflammatory bowel disease flare-ups.

Long-term response in patients who were in full remission by day 30 was assessed after one year, and a prolonged clinical response was seen in 55% of patients with CD and 80% of patients with UC. This difference is not statistically significant (p = ns). Results obtained in our study seem more favorable than those reported by Faubion et al. (16), who described a maintained response rate at 1 year of 49% in UC, and merely of 32% in CD; however, these studies cannot be statistically compared. We could not analyze the presence of predictive factors for relapse in our investigation, due to the number of patients enrolled for long-term follow-up, and to the characteristics of the methodology used. In UC remission, variables such as younger age and presence of previous repeat flare-ups have been suggested as independent predictive factors for disease relapse (23). In CD remission, however, no clinical factors with long-term predictive value are known (24).

Patients with a good response at day 30 were followed up for one year. Seven patients with EC (24%) and none with UC (0%) exhibited a steroid-dependent course, defined as their inability to discontinue steroid therapy without symptom relapse. These findings are consistent with those of Munkholm, who showed a steroid dependency rate of 36% in CD (15). Subsequently, Franchimont et al. identified younger age, smoking, oral contraceptive use, and colon or perianal disease as risk factors for steroid dependency (25).

To conclude, the rate of response to corticoids during severe, hospitalization-requiring first inflammatory bowel disease flare-ups is 64.4% for CD and 60.9% for UC, with response persisting in more than half of patients after one year. Data from our study allows no variables able of reliably predicting response to steroid therapy to be identified.

REFERENCES

1. Fraser AG, Orchard TR, Jewell DP. The efficacy of azathioprine for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: a 30 year review. Gut 2002; 50: 485-9. [ Links ]

2. Shepherd HA, Barr GD, Jewell DP. Use of an intravenous steroid regimen in the treatment of acute Crohn' disease. J Clin Gastroenterol 1986; 8: 154-9. [ Links ]

3. Oshitani N, Kitano A, Matsumoto T, Kobayashi K. Corticosteroids for the management of ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol 1995; 30 (Supl.) 8: 118-20. [ Links ]

4. Summers RW, Switz DM, Sessions JT, Becktel JM, Best WR, Kern F, et al. National cooperative Crohn' disease study; results of drug treatment. Gastroenterology 1979; 77: 847-69. [ Links ]

5. Malchow H, Ewe K, Brandes JW, Goebell H, Ehms H, Summer H, et al. European cooperative Crohn' disease study (ECCDS): results of drug treatment. Gastroenterology 1984; 86: 249-66. [ Links ]

6. Cohen RD, Stein R, Hanauer SB. Intravenous cyclosporin in ulcerative colitis: a five year experience. Am J Gastroenterol 2000; 95: 830. [ Links ]

7. Hyde GM, Thillainayagam AV, Jewell DP. Intravenous cyclosporin as rescue therapy in severe ulcerative colitis: time for a reappraisal?. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1998; 10: 411-3. [ Links ]

8. Santos JV, Baudet JA, Casellas F, Guarner L, Vilaseca J, Malagelada JR. Efficacy of intravenous cyclosporine for steroid refractory attacks of ulcerative colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol 1995; 20: 285-9. [ Links ]

9. Paoluzi OA, Pica R, Marcheggiano A, Crispino P, Iacopini F, Iannon C, et al. Azathioprine or methotrexate in the treatment of patients with steroid-dependent or steroid-resistant ulcerative colitis: results of an open -label study on efficacy and tolerability in inducing and maintaining remission. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002; 16: 1571-80. [ Links ]

10. Alfandhli AA, McDonald JW, Feagan BG. Methotrexate for induction of remission in refractory Crohn disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003; (1): CD003459. [ Links ]

11. Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Targan S, Hanauer SB, Mayer L, van Hogerzand RA, et al. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn' disease. N Engl J Med 1999; 340: 1398-405. [ Links ]

12. Hodgson HJF, Bhatti M. Assessment of disease activity in ulcerative colitis and Crohn' disease activity. Inflamm Bowel Dis 1995; 1: 117-43. [ Links ]

13. Harvey RF, Bradshaw JM. A simple index of Crohn' disease activity. Lancet 1980; 1: 514. [ Links ]

14. Rachmilewitz D. Coated mesalazine (5-aminosalicylic acid) versus sulphasalazine in the treatment of active ulcerative colitis: A randomized trial. BMJ 1989; 298: 82-6. [ Links ]

15. Munkholm P, Langholz E, Davidsen E, Binder V. Frequency of glucocorticoid resistance and dependency in Crohn' disease. Gut 1994; 35: 360-2. [ Links ]

16. Faubion WA, Edward V, Loftus JF, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Sandborn J. The natural history of costicosteroid therapy for inflamatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Gastroenterology 2001: 121: 255-60. [ Links ]

17. Kornbluth A, Marion J-F, Salomon P, Janowitz HD. How effective is current medical therapy for severe ulcerative and Crohn' colitis? J Clin Gastroentol 1995; 20: 280-4. [ Links ]

18. Medina C, Vergara M, Casellas F, Lara F, Naval J, Malagelada JR. Influencia del hábito tabáquico en la cirugía de la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 1998; 90: 771-4. [ Links ]

19. Gelbmann CM. Position of treatment refractoriness in ulcerative colitis and Crohn' disease-Do we have reliable markers? Inflam Bowel Diseases 2000; 6: 123-31. [ Links ]

20. Malchow H, Steinhardt HJ, Lorenz-Meyer H. Feasability and effectiveness of a defined-formula diet regimen in treating active Crohn' disease. European Cooperative Crohn' Disease Study III. Scand J Gastroenterol 1990; 25: 235-44. [ Links ]

21. Lindgren SC, Flood LM, Kilander AF, Löfberg R, Persson TB, Sjödahl RI. Early predictors of glucocorticoids treatment failure in severe and moderately severe attacks of ulcerative colitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1998; 10: 831-5. [ Links ]

22. Travis SPL, Farrant JM, Rickets C, Nolan DJ, Mortensen NM, Kettlewell MGW, et al. Predicting outcome in severe ulcerative colitis. Gut 1996; 38: 905-10. [ Links ]

23. Bitton A, Peppercorn MA, Antonioli DA, Niles JL, Shah S, Bousvaros A, et al. Clinical, biological and histologic parameters as predictors of relapse in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2001; 120: 13-20. [ Links ]

24. Loftus EV, Schoenfeld P, Sandborn WJ. The epidemiology an natural history of Crohn' disease in population-based patient cohorts from North America: a systematic review. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002; 16: 51-60. [ Links ]

25. Franchimont DP, Louis E, Croes F, Belaiche J. Clinical pattern of corticosteroid dependent Crohn' disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1998; 10: 821-5. [ Links ]

texto en

texto en