Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.98 no.5 Madrid may. 2006

ORIGINAL PAPERS

Risk factors associated with Helicobacter pylori infection. A population-based study conducted in the province of Ourense

Factores de riesgo asociados a la infección por Helicobacter pylori. Un estudio de base poblacional en la provincia de Ourense

R. Macenlle García, P. Gayoso Diz1, R. A. Sueiro Benavides2 and J. Fernández Seara

Service of Digestive Diseases and 1Investigation Unit. Complejo Hospitalario de Ourense. Ourense, Spain.

2Laboratory of Microbiology. Instituto de Investigación y Análisis Alimentario. University of Santiago de Compostela. A Coruña, Spain.

ABSTRACT

Objectives: to identify the relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and various factors that have been described in other studies in the general adult population in the province of Ourense.

Material and methods: three hundred and eighty-three participants were enrolled in a study on the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection. All participants filled in a questionnaire under supervision, and the data obtained were examined by means of a univariate analysis. The odds ratio corresponding to each variable studied was calculated with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Furthermore, a multivariate analysis was performed.

Results: the univariate analysis revealed an association between infection and: age, place of residence during childhood, current social status based on the head of the family's profession, current blue collar/white collar profession of the head of the family, sharing a bedroom during childhood, type of drinking water, and contact with animals during childhood. No association was found with respect to the presence of dyspeptic symptoms. The multivariate analysis disclosed that only age is an independent risk factor associated with infection.

Conclusion: age has been identified as the only independent risk factor associated with Helicobacter pylori infection in this population-based study. The univariate analysis has detected other factors. No association has been identified with respect to dyspeptic symptoms.

Key words: Helicobacter pylori. Epidemiology. Risk factor.

RESUMEN

Objetivos: identificar en la población general adulta de la provincia de Ourense, la relación entre la infección por Helicobacter pylori y diversos factores que se han descrito en otros estudios.

Material y métodos: se han incluido los 383 participantes en un estudio de prevalencia de la infección por Helicobacter pylori. Todos han completado un cuestionario bajo supervisión y los datos se han examinado mediante análisis univariante. Se han calculado las odds ratio correspondientes a cada variable estudiada, con sus intervalos de confianza al 95%. Además, se ha efectuado un análisis multivariante.

Resultados: el análisis univariante demuestra asociación de la infección con: edad, lugar de residencia en la infancia, clase social actual por la profesión del cabeza de familia, profesión no manual/manual del cabeza de familia actual, compartir dormitorio en la infancia, tipo de agua de consumo y el contacto con animales en la infancia. No se ha encontrado asociación con la presencia de síntomas dispépticos. El análisis multivariante ha mostrado que solamente la edad es un factor de riesgo independiente asociado a la infección.

Conclusión: en este estudio de base poblacional la edad es el único factor de riesgo independiente que se ha identificado asociado a la infección por Helicobacter pylori. En el análisis univariante se han identificado otros factores. No se demuestra asociación con síntomas dispépticos.

Palabras clave: Helicobacter pylori. Epidemiología. Factor de riesgo.

Introduction

Numerous epidemiological studies have been carried out worldwide in an attempt to identify risk factors involved in the acquisition of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection (1-3); they often obtained contradictory results, albeit associations with age, overcrowding, and socioeconomic status (3-7) have been found overall. Knowing what risk factors are involved is important if we are to adopt measures aimed at preventing its spread, as well as to identify populations at high risk of infection, particularly in areas where there is a high prevalence of associated conditions (3). The objective of the present study has been to attempt to identify risk factors associated with H. pylori infection in the general adult population of the province of Ourense, using a randomly selected population-based sample.

Material and methods

Patients

Three hundred and eighty-three participants randomly selected from the general adult population of the province of Ourense and who consented to participate in a prevalence study of H. pylori infection were enrolled (the selection methodology applied was reported in a previous study).

Measures and variables analyzed

All subjects were interviewed by the same specialist in Gastroenterology. Information was collected with respect to different variables: gender, age, place of residence, and number of people living together (during childhood and adulthood), having lived/living in an institution, immigration, level of education, social class (during childhood and current), blue collar/white collar profession (of the participant or head of family), sharing a bedroom or bed during childhood, drinking water from fountains and wells, contact with pets (dogs, cats) during childhood, tobacco and alcohol use, family history of peptic ulcer, personal history of endoscopic examination of the upper gastrointestinal tract, and presence of current or recent gastrointestinal symptoms (in the preceding 12 months). When examining the "place of residence' variable, an urban population was defined as having more than 50,000 inhabitants. For the "number of people living together' parameter, the cutoff point was set at 6 individuals. The categories proposed and published by the Task Force of "Sociedad Española de Epidemiología' (Spanish Epidemiology Society) and "Sociedad Española de Medicina de Familia y Comunitaria' (Spanish Society of Family and Community Medicine) (8) were used to evaluate level of education and social class, albeit with two modifications. A comprehensive, six-level classification was applied to examine "level of education', which includes illiterate individuals and people without any formal education in the same group: level 0. With respect to "social class', class VI has been incorporated as comprised of members of the armed services, priests, and religious lay assistants, as the index publication fails to indicate which of the other social classes these individuals should be included in (Table I). In the analysis of the relationship between infection and social class according to profession, housewives and students were excluded and then included in the analysis based on social class according to the profession of their head of family. White collar workers have been contemplated as professions assigned to social classes I, II, IIIA, and VI, whereas blue collar workers are those whose professions are included in classes IIIB, IIIC, IVA, IVB, and V. The presence of the following upper GI tract symptoms was assessed: heartburn, regurgitation, dysphagia, nausea, vomiting, pain/discomfort, and heaviness/bloating, regardless of frequency or severity. The categories accepted for the remaining variables are presented in tables II to V.

Statistical analysis

Data have been analyzed using the SPSS software package, version 10.0 (SPSS. Inc. Chicago. IL. USA), with a 95% level of confidence. For the purposes of analyzing the relationship between infection and the various variables, individuals who are "non-infected' as a result of having undergone eradication treatment were included in the group of infected subjects, since the most logical supposition is that they harbored H. pylori for many years until its elimination. Quantitative variables were evaluated using mean values and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI); qualitative variables were analyzed using frequency and percentage, and both a univariate analysis and multivariate analysis were carried out. Significant differences were defined as those having a p value < 0.05.

In order to analyze the association between quantitative variables, Student's t test was used to compare means or Pearson's correlation coefficient. Percentages were compared using the Chi-squared test. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% CIs for each possible risk factor of H. pylori infection were calculated in order to estimate the magnitude of association in terms of risk. An unconditional logistics regression was performed with H. pylori infection as the dependent variable, and the factors that the univariate analysis revealed as being associated with said infection as independent variables, as well as potential confounding factors. A backward strategy was used for modeling.

Analysis of non-respondents

A sample of 20% of subjects who refused to participate in the study was chosen at random; they were interviewed using the same questionnaire used with study participants.

Results

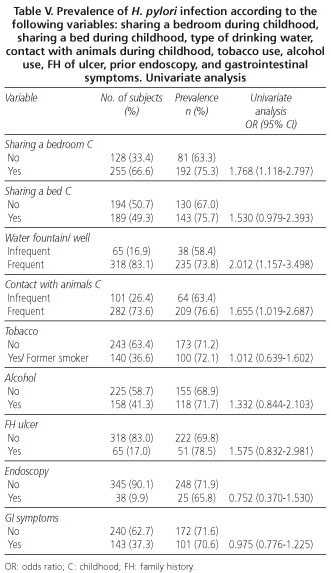

Three hundred and eighty-three subjects were studied, of which 265 were infected. After including the 8 individuals who had undergone prior eradication treatment, we had a total of 273 subjects with active or past infection. Tables II through V show the results of the univariate analysis. No association was detected between gender and infection. Age, with an OR of 1.017 (95% IC: 1.004-1.031), was found to be associated with an increased risk of having the infection, and upon intergroup analysis, taking the lowest prevalence group (18-24 years) as a reference, we found that risk was associated with the following age cohorts: 45-54, 55-64, and 75-84.

We also detected an association between infection and: a) place of residence during childhood (OR: 2.503); b) social class according to the profession of the current head of family (OR: 2.149); c) the current head of family having a blue collar/white collar profession (OR: 2.149); d) sharing a bedroom during childhood (OR: 1.768); e) type of drinking water (OR: 2.012); and f) contact with animals during childhood (OR: 1.655). A trend towards an association with social class according to the subject's profession, the subject having a blue collar/white collar profession, social class according to profession of the head of family during childhood, blue collar/white collar profession of the head of family during childhood, and sharing a bed during childhood has also been observed. For the remaining variables, no association or trend towards association has been revealed. As with age, the category having the lowest prevalence was taken as the reference category for the intergroup comparison of the "level of education' variable; risk was seen to be associated with the lowest levels: 0, 1, and 2.

The result yielded by the multivariate analysis reveals that only age is an independent risk factor for infection, with an OR of 2.298 (95% CI: 1.363-3.874). Living in rural areas during childhood revealed a strong trend towards direct correlation with infection, with an OR of 1.714 (95% CI: 0.945-3.109). With the strategy applied, this study has demonstrated that none of the remaining variables analyzed acts as an infection-related independent risk factor.

Twenty percent of non-participants were chosen at random to comprise a 44-member sample. This sample has similar characteristics to those found in the respondents, albeit with some differences. Fewer gastrointestinal symptoms were found in the sample of non-respondents; thus, nine individuals in this group reported GI symptoms, representing 20.4% of the sample, versus 37.3% in the group of respondents (p < 0.05) and 20.4% of individuals with a history of immigration, which is significantly lower than the 44.1% seen for respondents (p < 0.05).

Discussion

We believe the sample studied to be representative of the general adult population of the province of Ourense, and that the study results can be extrapolated to the adult population of this province at large. The main limitation to this study was a low rate of participation, approximately 60%. However, a sample of people who refused to participate was included, and few differences were found between non-respondents and study participants. The most striking difference has to do with the presence of gastrointestinal symptoms, which was higher among participants; perhaps because they were mostly interviewed in person, whereas non-respondents were mainly interviewed by phone. It is possible that direct contact will elicit a clearer account of symptoms being sought and a greater recall of these symptoms when they are infrequent.

Insofar as the risk factors studied are concerned, there is a direct association between infection and age in both the univariate and multivariate analyses. An increase in prevalence is observed, which peaks in the middle-aged cohort and subsequently falls, a finding that is consistent with reports by other researchers (9-13). This growing prevalence rate is generally deemed to be a cohort effect and to denote worse socioeconomic conditions and poorer hygiene in the past, which fostered infection (14); some authors such as Veldhuyzen van Zaten et al. (15) suggest that there is a continued risk of infection though. The previously discussed decrease in prevalence among elderly subjects has been attributed to the development of gastric atrophy, and consequently to the development of a microenvironment unsuitable for H. pylori survival, the germ then disappearing from the gastric mucosa (16).

Malaty et al. (17) identified a rural origin as an independent risk factor associated with infection. In the present study, although a direct correlation between having lived in a rural area during childhood was detected in the univariate analysis, the same relation did not hold up in the multivariate analysis, although a strong trend in this direction was observed. Moreover, as in other studies (16,18), no association with current place of residence was identified, despite its having been reported in several works (19,20). On occasion, a large number of people living together have been identified as a relevant risk factor (21-23); however we were unable to corroborate this finding. Nor can we substantiate a relation to gender, which is in fact consistent with most published studies (4,5,9,13,24-26), as opposed to those in which a higher prevalence rate was identified in males (27-30). A greater prevalence has been reported in the lower social classes, which has typically been evaluated in terms of level of education, type of occupation, or yearly income (9,13,18,26,27). Some studies found this relation exclusively regarding social class during childhood (17,31). In this work, the socioeconomic status was evaluated in several ways and, although the univariate analysis documented an association or a strong trend towards a correlation between some of these variables and infection -for example, the current head of family having a blue collar profession- the multivariate analysis failed to identify any as an independent risk factor. Just over forty-four percent (44.1%) of participants were immigrants, which might also be considered an indicator of belonging to a lower social class at present or in the past. However, no association between this variable and infection was observed.

The lack of correlation with tobacco and alcohol use is in line with the results of several works (4,9,13, 24,26), albeit with certain exceptions, since Murray et al. (25) found a direct correlation with smoking. There are also conflicting results with respect to alcohol use; thus, Brenner et al. (32) and Kuepper-Nybelen et al. (33) found a reverse correlation with high alcohol use, whereas Hook-Nikane et al. (34) observed a large trend towards a direct association. A higher prevalence has been reported in people who have been in institutions such as orphanages or residences for the elderly, something we were unable to confirm (35,36). Some studies demonstrated higher prevalence rates in individuals who shared a bedroom or bed during childhood, while others failed to find any such association (6,10,21,37-40). In this case, the univariate analysis showed that sharing a bedroom or bed during childhood had a direct association or large trend towards increased prevalence, respectively. Frequent contact with domestic animals, primarily dogs and cats, has been identified at times as being a risk factor for the acquisition of infection, whereas other authors have observed a reverse relationship or, as in this study, a lack of association (18,41-43). Common consumption of water from fountains or wells presents a direct correlation with infection in the univariate analysis, which endorses the hypothesis of its role as a vehicle for transmission. Also in Spain, Santana et al. (44) and Martín de Argila et al. (45) detected this association, albeit this has not been the case with other authors (18,46,47).

Although a higher prevalence rate has been reported in individuals with a personal history of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (24) and a family history of peptic ulcer (24,48-50), we found no association with either one of these variables. Nor have we found an association with upper GI symptoms, a finding in common with other studies (21,24,26,27,51), although other researchers have detected said association (50).

In conclusion, this study reveals that in the general adult population of the province of Ourense, age is the only independent risk factor associated with H. pylori infection, whereas the place of residence during childhood shows a strong trend towards a direct correlation with said infection. It is possible that other variables may be relevant as risk factors, but the high correlation between some of them (social class, number of people living together, place of residence,...) may indicate an effect on infection when analyzed independently, although said effect may be lost once they are incorporated into the joint model due to colinearity.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their gratitude to Dr. Adolfo Figueiras at Department of Preventive Medicine, Universidad de Santiago de Compostela, for his collaboration in the drafting of this manuscript.

References

1. Bardhan PK. Epidemiological features of Helicobacter pylori infection in developing countries. Clin Infect Dis 1997; 25: 973-8. [ Links ]

2. Cover TL. Commentary: Helicobacter pylori transmission, host factors, and bacterial factors. Gastroenterology 1997; 113 (Supl. 1): S29-S30. [ Links ]

3. Go MF. Review article: natural history and epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002; 16 (Supl. 1): 3-15. [ Links ]

4. Baena JM, García M, Martí J, León I, Muñiz D, Teruel J, et al. Prevalencia de la infección por Helicobacter pylori en atención primaria: estudio seroepidemiológico. Aten Primaria 2002; 29 (9): 553-7. [ Links ]

5. Abasiyanik MF, Tunc M, Salih BA. Enzyme immunoassay and immunoblotting analysis of Helicobacter pylori infection in Turkish asymptomatic subjects. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2004; 50 (3): 173-7. [ Links ]

6. Aguemon BD, Struelens MJ, Massougbodji A, Ouendo EM. Prevalence and risk factors for Helicobacter pylori infection in urban and rural Beninese populations. Clin Microbiol Infect 2005; 11 (8): 611-7. [ Links ]

7. Farrell S, Doherty GM, Milliken I, Shield MD, MacCallion WA. Risk factors for Helicobacter pylori infection in children: an examination of the role played by intrafamilial bed sharing. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2005; 24 (2): 149-52. [ Links ]

8. Domingo-Salvany A, Regidor E, Alonso J, Álvarez-Dardel C, Borrell C, Doz F, et al. Grupo de Trabajo de la Sociedad Española de Epidemiología y de la Sociedad Española de Medicina de Familia y Comunitaria. Una propuesta de medida de la clase social. Atención Primaria 2000; 25 (5): 350-63. [ Links ]

9. Cilla G, Pérez-Trallero E, García-Bengoechea M, Marimón JM, Arenas JI. Helicobacter pylori infection: a seroepidemiological study in Guipúzcoa, Basque Country, Spain. Euro J Epidemiol 1997; 13: 945-9. [ Links ]

10. Luzza F, Imeneo M, Paluccio G, Giancotti A, Perticone F, Foca A et al. Seroepidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection and hepatitis A in a rural area: evidence against a common mode of transmission. Gut 1997; 41: 164-8. [ Links ]

11. Rodrigo L, Riestra S, Fernández E, Fernández MR, García S, Lauret ME. Estudio epidemiológico de la infección por Helicobacter pylori en la población general de Asturias. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 1997; 89 (7): 511-6. [ Links ]

12. Glupczynski Y, Bourdeaux L, Verhas M, DePerez C, DeVos D, Devreker T. Use of a urea breath test versus invasive methods to determine the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in Zaire. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1992; 11 (4): 322-7. [ Links ]

13. Bazzoli F, Palli D, Zagari RM, Festi D, Pozzato P, Nicolini G, et al. The Loiano-Monghidoro population-based study of Helicobacter pylori infection: prevalence by 13C-urea breath test and associated factors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001; 15 (7): 1001-7. [ Links ]

14. Banatvala N, Mayo K, Megraud F, Jennings R, Deeks JJ, Feldman RA. The cohort effect and Helicobacter pylori. J Infect Dis 1993; 168: 219-21. [ Links ]

15. Veldhuyzen van Zaten SJO, Pollack T, Best LM, Bezanson GS, Marrie T. Increasing prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection with age: continuous risk of infection in adults rather than cohort effect. J Infect Dis 1994; 169: 434-7. [ Links ]

16. Valle J, Kekki M, Sipponen P, Ihamäki T, Siurala M. Long-term course and consequences of Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Scand J Gastroenterol 1996; 31: 546-50. [ Links ]

17. Malaty HM, Graham DY. Importance of childhood socioeconomic status on the current prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Gut 1994; 35: 742-5. [ Links ]

18. Fiedorek SC, Malaty HM, Evans DL, Pumphrey CL, Casteel HB, Evans DJ, et al. Factors influencing the epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection in children. Pediatrics 1991; (3): 578-82. [ Links ]

19. Bosco J, Biondi V, Luna S, Moreno M, Senra A. Prevalencia de la infección por Helicobacter pylori en dos áreas geográficas con distinta mortalidad por cáncer de estómago. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 1998; (Supl. 1): 28. [ Links ]

20. Castellot A, Santana E, Orengo JC, Peña L, Santana M, Sierra A, et al. Seroprevalencia de la infección por Helicobacter pylori en las Islas Canarias. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2003; 93 (Supl. 1): 153. [ Links ]

21. Breuer T, Sudhop T, Hoch J, Sauerbruch T, Malfertheiner P. Prevalence of and risk factors for Helicobacter pylori infection in the western part of Germany. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1996; 8: 47-52. [ Links ]

22. Fall CHD, Goggin PM, Hawtin P, Fine D, Duggleby S. Growth in infancy, infant feeding, childhood living conditions, and Helicobacter pylori infection at age 70. Arch Dis Child 1997; 77 (4): 310-4. [ Links ]

23. Goodman K, Correa P. Transmission of Helicobacter pylori among siblings. The Lancet 2000; 355: 358-62. [ Links ]

24. Gasbarrini G, Pretolani S, Bonvicini F, Gatto MRA, Tonelli E, Megraud F, et al. A population based study of Helicobacter pylori infection in a European country: the San Marino Study. Relations with gastrointestinal diseases. Gut 1995; 36: 838-44. [ Links ]

25. Murray LJ, McCrum EE, Evans AE, Bamford KB. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection among 4742 randomly selected subjets from Northen Ireland. Int J Epidemiol 1997; 26 (4): 880-7. [ Links ]

26. Rafols A, Solanas P, Ramio G, Suelves N, Rodríguez C, González C, et al. Prevalencia de la infección por Helicobacter pylori en atención primaria de salud. Aten Primaria 2000; 25 (8): 104-11. [ Links ]

27. Carballo F, Martínez C, Aldeguer M, García A, Domínguez E, Malfertheiner P, et al. Infección por Helicobacter pylori en Guadalajara: prevalencia y factores asociados. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 1995; 87 (Supl. 1): 7. [ Links ]

28. Reploge ML, Glaser SL, Hiatt RA, Parsonnet J. Biologic sex as a risk factor for Helicobacter pylori infection in healthy young adults. Am J Epidemiol 1995; 142 (8): 856-63. [ Links ]

29. González JA, Gómez C, García-Cano J, Nieto J, Morillas J, Pérez JI, et al. Infección por Helicobacter pylori en población sana en la provincia de Cuenca. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2003; 95 (Supl. 1): 52. [ Links ]

30. Windsor HM, Abioye-Kuteyi EA, Leber JM, Morrow SD, Bulsara MK, Marshall BJ. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in indigenous western australians: comparison between urban and remote rural populations. Med J Aust 2005; 182 (5):210-3. [ Links ]

31. Gause-Nilsson I, Gnarpe H, Gnarpe J, Lundborg P, Steen B. Helicobacter pylori serology in elderly people: a 21-year cohort comparison in 70-year-olds and 20-year longitudinal population study in 70-90-year-olds. Age and Aging 1998; 27: 433-6. [ Links ]

32. Brenner H, Rothenbacher D, Bode G, Adler G. Relation of smoking and alcohol and coffee consumption to active Helicobacter pylori infection: cross sectional study. Br Med J 1997; 315: 1489-92. [ Links ]

33. Kuepper-Nybelen J, Thefeld W, Rothenbacher D, Brenner H. Patterns of alcohol consumption and Helicobacter pylori infection: results of a population-based study from Germany among 6545 adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005; 21 (1): 57-64. [ Links ]

34. Höök-Nikanne J. Effect of alcohol consumption on the risk of Helicobacter pylori infection. Digestión 1991; 50: 92-8. [ Links ]

35. Pérez-Pérez GI, Taylor DN, Bodhidatta L, Wongsrichanalai J, Baze WB, Dunn BE, et al. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infections in Thailand. J Infect Dis 1990; 161: 1237-41. [ Links ]

36. Pilotto A, Malfertheiner P. Review article: an approach to Helicobacter pylori infection in the elderly. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002; 16 (4): 683-91. [ Links ]

37. Goodman KJ, Correa P. The transmission of Helicobacter pylori. A critical review of the evidence. Int J Epidemiol 1995; 24 (5): 875-87. [ Links ]

38. Rocha GA, Oliveira AMR, Queiroz DMM, Mendes EN, Moura SB, Rabello ALT, et al. High seroconversion for Helicobacter pylori in children. Gut 1995; 37 (Supl. 1): A27. [ Links ]

39. Olmos JA, Rios H, Higa R and the Argentinean Hp Epidemiologic Study Group. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in Argentina. J Clin Gastroenterol 2000; 31 (1): 33-7. [ Links ]

40. Malaty HM, Logan ND, Graham DY, Ramchatesingh JE. Helicobacter pylori infection in preschool and school-aged minority children. Effect of socioeconomic indicators and breast-feeding practices. Clin Infect Dis 2001; 32: 1387-92. [ Links ]

41. Sahay P, Axon ATR. Reservoirs of Helicobacter pylori and modes of transmission. Helicobacter 1996; 1 (3): 175-82. [ Links ]

42. Bode G, Rothenbacher D, Brenner H, Adler G. Pets are not a risk factor for Helicobacter pylori infection in young children: results of a population-based study in Southern Germany. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1998; 17: 909-12. [ Links ]

43. Kearney D, Crump C. Domestic cats and dogs and home drinking water source as risk factors for Helicobacter pylori infection in the United States. Gastroenterology 2002; 122 (4): A209. [ Links ]

44. Santana M, Marrero MJ, Sierra A, Peña L, Santana E, Monescillo A, et al. Helicobacter pylori. Aspectos epidemiológicos en la población infantil de Gran Canaria. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 1998; 90 (Supl. 1): 153. [ Links ]

45. Martín de Argila C, Boixeda D, González A, Bornemann M, Saiz JC, García A. Infección por Helicobacter pylori en el medio rural ¿es diferente a lo que ocurre en el medio urbano? Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2001; 93 (Supl. 1): 158-9. [ Links ]

46. Mitchell HM, Li YY, Hu PJ, Liu Q, Chen M, Du GG, et al. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori in Southern China: identification of early childhood as the critical period of adquisition. J Infect Dis 1992; 166: 149-53. [ Links ]

47. Everhart JE, Kruszon-Morán D, Pérez-Pérez GI, Tralka TS, McQuillan G. Seroprevalence and ethnic differences in Helicobacter pylori infection among adults in the United States. J Infect Dis 2000; 181: 1359-63. [ Links ]

48. Brenner H, Rothenbacher D, Bode G, Adler G. Parental history of gastric or duodenal ulcer and prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in preschool children: population based study. Br Med J 1998; 316: 665. [ Links ]

49. Martín de Argila C, Boixeda D, Cantón R, Mir N, de Rafael L, Gisbert J, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection in a healthy population in Spain. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1996; 8 (12): 1165-8. [ Links ]

50. Parente F, Maconi G, Sangaletti O, Minguzzi M, Vago L, Rossi E, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and related gastroduodenal lesions in spouses of Helicobacter pylori positive patients with duodenal ulcer. Gut 1996; 39: 629-33. [ Links ]

51. Caballero AM, Sofos S, Valenzuela M, Martín JL, Casado FJ, Guilarte J. Epidemiología de la dispepsia en una comunidad del sur de España. Prevalencia de la infección por Helicobacter pylori. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2000; 92 (12): 781-6. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Ramiro Macenlle García.

Servicio de Aparato Digestivo.

Complejo Hospitalario de Ourense.

C/ Ramón Puga, 54.

32005 Ourense.

e-mail: macenlle@mixmail.com

Recibido: 06-10-05.

Aceptado: 19-12-05.

texto en

texto en