Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.101 no.9 Madrid sep. 2009

Laparoscopic surgery into mixed hiatal hernia. Results pre-operative and post-operative

Tratamiento quirúrgico laparoscópico en la hernia de hiato mixta. Resultados peroperatorios y del seguimiento a medio plazo

A. Pagán Pomar, E. Palma Zamora, A. Ochogavia Segui and M. Llabres Rosello1

Service of General Surgery. Hospital Universitario Son Dureta. Palma de Mallorca, Spain.

1Service of Digestive Diseases. Hospital Comarcal de Inca. Palma de Mallorca, Spain

ABSTRACT

Introduction: the complications of the mixed hernia need, often, surgical treatment. In the asymtomatic patients this one treatment is controversial, due to her complex repair and the high percentage of relapse informed in the long term. The surgical classic routes, they present raised morbi-mortality related to the extent of the incisions, to long hospitable stays and slow recovery.

Material and methods: between October, 2001 to November, 2007 we check 39 patients with hernia hiatal mixed with a middle ages of 65 years (35-78 years). In Lloyd-Davies's position, the content diminishes hernia and the redundant sack is resected. The diaphragmatic props are sutured by material not reabsorbable. Mesh of reinforcement intervened in 7/39 repairs. It concludes with a partial or complete antirreflux depending on the report.

Results: the operative average time was of 126 min; the hospital stay of 2.46 days. The complications perioperatives are principally cardiorespiratory. A patient died for an intestinal inadvertent perforation during the intervention and of late diagnosis. We realize traffic gastroduodenal to 12 months in 28 patients (71.7%). We find relapse in 8 patients (20.5%). Four asymtomatic patients, with chance find in the radiological control. Three patients with pirosis that needs treatment and one of the relapses needed reintervention for strangulation of a gastric volvulus.

Conclusions: the laparoscopic surgery offers safety and efficiency with rapid postoperatory recovery, minor morbidity and hospitable stay. After the surgery, the long-term relapse presents similar results to the opened surgery, though the interposition of mesh can propitiate her decrease.

Key words: Hiatal hernia. Diaphragma hernia. Paraesophageal hernia. Laparoscopic antirreflux surgery. Prosthetic hiatal closure.

RESUMEN

Introducción: las complicaciones de la hernia mixta requieren, con frecuencia, tratamiento quirúrgico. En los pacientes asintomáticos este tratamiento es controvertido, debido a su compleja reparación y al elevado porcentaje de recidivas informado a largo plazo. Las vías quirúrgicas clásicas presentan elevada morbimortalidad relacionada con la amplitud de las incisiones, con largas estancias hospitalarias y lenta recuperación.

Material y métodos: entre octubre de 2001 a noviembre de 2007 revisamos 39 pacientes con hernia hiatal mixta con una edad media de 65 años (35-78 años). En posición de Lloyd-Davies, se reduce el contenido herniario y se reseca el saco redundante. Se suturan los pilares diafragmáticos con material no reabsorbible. Se interpuso malla de refuerzo en 7/39 reparaciones. Se finaliza con un antirreflujo parcial o completo dependiendo del informe manométrico.

Resultados: el tiempo operatorio medio fue de 126 min. La estancia hospitalaria de 2,46 días. Las complicaciones perioperatorias son principalmente cardiorrespiratorias. Un paciente falleció por una perforación intestinal inadvertida durante la intervención y de diagnóstico tardío. Realizamos tránsito gastroduodenal a los 12 meses en 28 pacientes (71,7%). Encontramos recidiva en 8 pacientes (20,5%). Cuatro pacientes asintomáticos, con hallazgo casual en el control radiológico. Tres pacientes con pirosis que requiere tratamiento y una de las recidivas precisó reintervención por estrangulación de un vólvulo gástrico.

Conclusiones: la laparoscopia ofrece seguridad y eficacia con rápida recuperación postoperatoria, menor morbilidad y estancia hospitalaria. Tras la cirugía, la recidiva a largo plazo presenta similares resultados a la cirugía abierta, aunque la interposición de malla puede propiciar su disminución.

Palabras clave: Hernia hiatal. Hernia diafragmática. Hernia paraesofágica. Fundoplicatura laparoscópica. Reparación con malla.

Introduction

The hiatal hernia can be classified into 3 groups; the sliding hiatal hernia or type I, the paraesophageal hiatal hernia or type II, and the mixed hernia or type III. This last type, depending on the content (bowel, oment, spleen...), could form a forth group in this classification (1).

Type I is by far the most frequent one, types II and III constituting less than 5% of all hiatal hernias. When there is a long evolution, the difference in pressure between the thoracic and the abdominal cavity, and the laxity of the phrenoesphageal membrane and the gastroesophageal attachment elements cause an increase in hernia volume. This may also be accompanied by a gastric slide and the eventual formation of a mesentericaxial gastric volvulus, the most frequent cause being a vascular pedicle fixation.

Traditionally, these hernias have been treated by toracotomy or laparotomy. However, the results of several series of operations have shown that not only is the laparoscopic approach more feasible and safe, but it also offers a wider therapeutic alternative with excellent short term results compared to open repairs (2,3). It has been shown that there is a high incidence of recurrence in groups controlled by barium transit, in laparoscopic repair too (4,5), whose surgical indication requires caution in asymptomatic hernia type III (6).

In this study, we offer our experience and the results obtained in the laparoscopic treatment of 39 mixed hernias, including post-operative radiological evaluations.

Material and methods

Between October 2001 and November 2007, we performed 175 laparoscopic fundoplications, 39 of which were mixed hernia corrections. Clinical information regarding complications or post-operative symptoms was obtained via personal interviews and quarterly following-ups.

We used a questionnaire, proposed by Shaw, on gastrointestinal symptoms (heartburn, retrosternal pain, dysphagia, pulmonary symptoms or bleeding) (7) and their severity -no symptoms (0), moderate but no medication (1), moderate with occasional medication (2), severe symptoms that need continuous treatment (3)-. Patients were clinically evaluated, before and after surgery, with the help of this questionnaire. Furthermore, by applying the Savary Miller classification, we practised an esophagoscopy in order to evaluate the degree of esophagitis. Whenever it was possible, pre-operative evaluation also included manometry and a 24-hour pH monitoring if symptoms or endoscopic findings were present.

Peristalsis was classified as normal when over 80% of peristaltic contractions of more than 30 mmHg were in the lower third of the esophagus, or low amplitude when over 80% of peristaltic contractions of less than 30 mmHg were in the same area. As part of the patients' follow-ups, a barium transit was performed a year after surgery.

Surgical technique

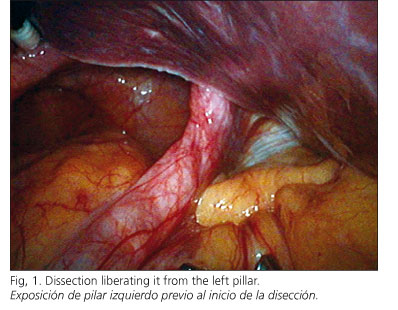

Patients were under general anesthesia and in the Lloyd-Davies position. Pneumoperitoneum was practiced (12 mmHg) with a Veres needle. Five operative laparoscopic ports were used; three of them 5 mm, for gastric traction, left hepatic lobe separation and the surgeon's left working hand. Hernia content reduction required a caudal maintained traction to avoid gastric reincorporation in the thoracic cavity until peritoneal adherences that fix the distal esophagus were completely liberated. We began the sack dissection liberating it from the left pillar (Fig. 1) and tractioning it to the right pillar, showing the esophagus body in the mediastinum until it was finally individualized with a ribbon that surrounded it to complete the retroesophagic dissection (Fig. 2). When the resulting peritoneal sack was redundant, we excised it to allow a good anchorage of the funduplication sutures.

For the dyaphragmatic closure, non-absorbable material was used. In the last 7 cases we used two types of mesh: PTFE dual mesh (WL Gore & Assoc®), and recently a colagen-poliester bilaminar mesh (Parietex composite®, Sofradim, Covidien®). In two of the cases, PTFE mesh was used, but at present we prefer Composite mesh because of its manageability and laxity that allows an easy anatomic adaptation, and comes presented in several pre-cut models (Fig. 3). In all cases, we have completed the operation using an anti-reflux technique.

Results

The 39 mixed hernias were divided into 37 type IIIs and 2 type IVs. Mixed hernias constituted 22.2% of all the hiatal hernias operated on in the given period. Regarding gender, 33 patients were women and 6 were men averaging 65 years old (35-78 years old). In the women's group, the average of 66 years old (47-75 years) was higher than in the men's group - 60 years old (35-78 years). Age range was between 35 and 78 years.

The most common pre-operative symptoms were retroesternal pain or epigastric oppression, dysphagia caused by solid food or anemia caused by chronic digestive bleeding. Heartburn was of little clinical relevance and was rare in this series (Table I).

The mixed hernia diagnosis was confirmed in all cases with a barium study. A mesentericaxial gastric volvulus was found in two patients. Endoscopy was done on 29 patients, of whom 11 had some degree of esophagitis: grade I; grade I: 6 patients, grade II: 5 patients and grade III: 1 patient.

Esophagus manometry was done on 22 patients to determine esophageal body motility and to programme the correct fundoplicature technique. A normal peristalsis or non-specific motor disorder was found in 19 patients, and a low amplitude peristalsis in 3 of them. Finally, 24-hour pH-metry was carried out in 21 cases, which confirmed the presence of gastroesophagic reflux in 4 of them.

Average surgical time was 125 min (70-240 min). The sack was removed in 19 patients, once the esophagus was completely liberated. Under calibration, dyaphragmatic pillar closure was done with no anterior closures in any of the cases. Mesh was needed in 7 patients because of pillar weakness. The anti-reflux technique used was the Nissen-Rossetti in 36 patients and the Toupet in 3 cases. No gastropexia or other fixation procedures were performed.

One patient needed open surgery because of an aortic wall lesion during the pillar suture. There was an aortic elongation near the left pillar, which was not noticed during the dissection. The injury occurred at the beginning of the pillar suture due to a direct puncture.

Two re-interventions were performed. One patient in the immediate post-operatorative period, who was initially diagnosed with cardiogenic shock due to an arrhythmogenic history, finally died of a multi-organ failure caused by an inadvertent intestinal perforation. Another re-intervention, which was performed 8 months after the initial operation, was a complicated gastric volvulus that required gastrectomy and the removal of the previously placed mesh, probably too small to cover the hiatus area.

The average period of hospitalization after surgery was 2.2 days. Except from four patients, all of them tolerated liquids 12 hours after their operations.

Oppression and retroesternal pain improved in all of the patients. Dysphagia, which usually appeared in the first post-operative month, improved subsequently, except in 3 cases that presented weak symptoms relating to solid food intake. No dilatation was needed.

A global relapse of 20.5% was observed after an average follow-up of 22.6 months (5.7-65.4 months). Radiological monitoring were carried out between 6 and 12 months after surgery revealing 4 relapses with no symptoms, as well as three patients who had a relapse with pyrosis that responded to a proton pump inhibitor (Table II).

Discussion

Laparoscopic correction of hiatal hernia is a safe and efficient alternative to traditional medical treatment (2,8). Although hiatal hernias are classified in 3 groups, some authors add a forth group related to hernia content (9).

Literature quantifies the frequency of mixed hiatal hernia in 5% of cases (10,11), but in our series it reached almost 23% of the cases. We believe, as other authors, that mixed hernias are the final stage of sliding hernias, and somehow indicate a delay in the diagnosis or the establishment of surgery.

Mixed hernias normally show gastric obstruction symptoms. As in other series, postprandial pain, retrosternal oppression and dysphagia are the most frequent, and can usually be ascribed to extrinsic compression of the stomach over the distal esophagus. The intermittent presentation of symptoms suggests a gastric rotation, due to the progressive laxity of anchoring structures, which in a long period will favour the appearance of complications. Although heartburn was not predominant, there were endoscopic findings of esophagitis in 30% of cases in our series. Depending on the realization of 24-hour pH-metry, this percentage varies between 19% by authors such as Myers and 67% by Gantert's series (12,13).

We consider ambulatory 24-hour monitoring an unnecessary examination for these hernias as in most of the cases it is informed as normal, and we associate fundoplication as part of the surgical correction. Manometric study, whenever feasible, will show the esophagic body peristalsis and establish the indication of partial fundoplication if there is a low amplitude peristalsis, whereas complete fundoplication normally associates with more frequent post-operative dysphagia (14-17). A symptomatic mixed hernia diagnosis is an indication of elective surgery for most authors. It prevents an emergency procedure due to an incarceration or strangulation. Consequently, this leads a morbidity and mortality close to 20%, determined by the age of the patients and their comorbidities (18-20).

Mixed hernia correction involved a greater, more complex risk of inter-operative complications. In our case, the aortic lesion related to an elongation. This complication has been previously described by Leggett (21).

Hernial sac resection, which used to arouse controversy (22,23), is nowadays considered to be an indispensable technical gesture (24,25). There is growing evidence pointing to reduced relapse in the mid term following placement of a mesh without increased complications (26-29). Granderath, among others, systematically recommends pillar closure using a mesh, considering that closure with simple sutures does not prevent the possibility of rupture and valve elevation. Although our use at the beginning of the series was limited due to the lack of consensus in literature, the technical complexity of its setting and the diversity of materials, we now believe that diafragmatic pillars showing tear or dilaceration during the simple suture should be strengthened with a mesh. There is no consensus on the appropriate type of mesh (27), so we have used two types, both double-sided designed for intraperitoneal placement, made with PTFE and polyester, being careful not to apply it to the esophagus. We currently use a polyester and hydolized collagen composite mesh because its features reduce the risk of a decubitus on neighbouring structures. Fixation was performed using nonresorbable suture, in some cases with helical sutures that were coated by applying a fibrin sealant (Tissucol®). The number of reported complications was low, but these may appear unusually late (27,30,31). To date, we have not had any complications relating to the interposition of the mesh or its fixations.

Although the use of an antireflux technique in the treatment of these large hernias is controversial (22,23), we always use it. We believe that it is justified on the basis that up to 18% of patients present pyrosis after a simple repair (32), and surgical dissection of the gastroesophageal union alters physiological anti-reflux mechanisms.

The quality of life has improved in most patients. This group also includes those taking proton-pump inhibitors, who needed surgery to relieve thoracic or epigastric pain, respiratory symptoms or dysphagia due to esophageal compression in the mediastinum (33).

The rate of recurrence probably depends on the follow-up duration and its definition. It could either be described as a disruption of the hiatal closure with fundoplication rising to the chest, or as the presence of asymptomatic hernial poles discovered with a barium transit. Our series presents a recurrence rate of 20.5%, although half of these cases were totally asymptomatic, thus over 85% of the patients reported outcome as good or very good in (33,34).

In conclusion, the use of laparoscopic surgery in the treatment of mixed hernias in not only more feasible and safe than open surgery, but it also reduces post-operative morbidity and hospitalization. A wide dissection of the gastroesophageal union and distal esophagus is needed, with a hernial sac resection. Hiatal reconstruction by placing a double-sided mesh must also be considered when diafragmatic pillars are not high-quality; there seems to be a consensus in which placement of a mesh decreases the relapse without increasing complications. The association of an anti-reflux technique (Nissen, Nissen-Rossetti or Toupet), seems to complete the technique offering a better alternative to these patients to avoid or to reduce the appearance of pyrosis.

References

1. Landrenau RJ, Del Pino M, Santos R. Management of paraesophageal hernias. Surg Clin N Am 2005; 85: 411-32. [ Links ]

2. Athanasakis H, Tzortzinis A, Tsiaoussis J, Vassilakis JS, Xynos E. Laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hernia. Endoscopy 2001; 51: 590-4. [ Links ]

3. Huntington TR. Short-term outcome of laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair. A case series of 58 consecutive patients. Surg Endosc 1997; 11: 894-8. [ Links ]

4. Hashemi M, Peters JH, DeMeester TR, Huprich JE, Queck M, Hagen JA, et al. Laparoscopic repair of large type III hiatal hernia: objective follow-up reveals high recurrence rate. J Am Coll Surg 2000; 190: 553-601. [ Links ]

5. Targarona EM, Bendaham G, Balague C, Garriga J, Trias M. Mallas en el hiato: una controversia no solucionada. Cir Esp 2004; 75(3): 105-16. [ Links ]

6. Stylopoulos N, Gazelle GS, Rattner DW. Paraesophageal hernias: operation or observation? Ann Surg 2002; 236(4): 492-501. [ Links ]

7. Shaw MJ, Talley NJ, Beebe TJ, Rockwood T, Carlsoson R, Adlis S, et al. Initial validation of a diagnostic questionnaire for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96: 52-7. [ Links ]

8. SAGES guidelines. Guidelines for surgical treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surg Endosc 1998; 12: 186-88. [ Links ]

9. Lal, DR, Pellegrini CA, Oelschlager BK. Laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hernia. Surg Clin N Am 2005; 85: 105-18. [ Links ]

10. Skinner DB, Belsey RH. Surgical management of esophageal reflux and hiatus hernia. Long-term results with 1030 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1967; 53: 33-54. [ Links ]

11. Sweet RH. Experience with 500 cases of hiatus hernia. J Thorac Surg 1962; 44: 145. [ Links ]

12. Myers G, Harms B, Starling J. Management of paraesophageal hernias with a selective approach to antireflux surgery. Am J Surg 1995; 170: 375-80. [ Links ]

13. Gantert WA, Patti MG, Arcerito M, Feo C, Stewart L, DePinto M, et al. Laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hiatal hernias. J Am Coll Surg 1998; 186: 428-32. [ Links ]

14. Catarci M, Gentileschi P, Papi C, Carrara A, Marrese R, Gaspari AL, et al. Evidence-based appraisal of antireflux fundoplication. Ann Surg 2004; 239: 325-37. [ Links ]

15. Watson DI, Jamieson GG, Lally C, Archer S, Bessell JR, Booth M, et al. Multicenter, prospective, double-blind, randomized trial of laparoscopic Nissen vs anterior 90º partial fundoplication. Arch Surg 2004; 139: 1160-7. [ Links ]

16. Pessaux P, Arnaud J-P, Ghavami B, Flament JB, Trebuchet G, Meyer C, et al. Laparoscopic antireflux surgery: comparative study of Nissen, Nissen-Rossetti, and Toupet fundoplication. Surg Endosc 2000; 14: 1024-7. [ Links ]

17. Herbella FAM, Tedesco P, Nipomnick I, Fisichella PM, Patti MG. Effect of partial and total laparoscopic fundoplication on esophageal body motility. Surg Endosc 2007; 21: 285-8. [ Links ]

18. Carter R, Brewer LA 3rd, Hinshaw DB. Acute gastric volvulus. A study of 25 cases. Am J Surg 1980; 140: 99-106. [ Links ]

19. Haas O, Rat P, Christophe M, Friedman S, Favre JP. Surgical results of intrathoracic gastric volvulus complicating hiatal hernia. Br J Surg 1990; 77: 1379-81. [ Links ]

20. Geha AS, Massad MG, Snow NJ, Baue AE. A 32-year experience in 100 patients with giant paraesophageal hernia: the case for abdominal approach and selective antireflux repair. Surgery 2000; 128: 623-30. [ Links ]

21. Leggett PL, Bissell CD, Churchman-Winn R. Aortic injury during laparoscopic fundoplication: an underreported complication. Surg Endosc 2002; 16(2): 362. [ Links ]

22. Kuster GG, Gilroy S. Laparoscopic technique for repair of paraesophageal hiatal hernias. J Laparoendosc Surg 1993; 3: 331-8. [ Links ]

23. Perdikis G, Hinder RA, Filipi CJ, Walenz T, McBride PJ, Smith SL, et al. Laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair. Arch Surg 1997; 132: 586-90. [ Links ]

24. Cuesta MA, vab der Poet DL, Klinkenberg-Knol EC. Laparoscopic treatment of large hiatal hernias. Semin Laparosc Surg 1999; 6: 213-23. [ Links ]

25. Vara Thorbeck C, Felices M, Toscazo R, Salvi M. Nuestra experiencia en el tratamiento de la hernia hiatal paraesofágica por vía laparoscópica. Cir Esp 2000; 68: 214-8. [ Links ]

26. Frantzides CT, Madan AK, Carlson MA, Stavropoulos GP. A prospective, randomized trial of laparoscopic polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) patch repair vs simple cruroplasty for large hiatal hernia. Arch Surg 2002; 137: 649-52. [ Links ]

27. Granderath FA, Carlson MA, Champion JK, Szold A, Basso N, Pointner R, et al. Prosthetic closure of the esophageal hiatus in large hiatal hernia repair and laparoscopic antireflux surgery. Surg Endosc 2006; 20: 367-79. [ Links ]

28. Objective follow-up after laparoscopic repair of large type III hiatal hernia. Assessment of safety and durability. World Surg 2007; 31: 2177-83. [ Links ]

29. Oelschlager BK, Pellegrini CA, Hunter J. Biologic prosthesis reduces recurrence after laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair. A multicenter, prospective, randomized trial. Ann Surg 2006; 244: 481-90. [ Links ]

30. Arendt T, Stuber E, Monig H. Dysphagia due to transmural migration of surgical material into the esophagus nine years after Nissen fundoplication. Gastrointest Endosc 2000; 51: 607-10. [ Links ]

31. Kemppainen E, Kiviluoto T. Fatal cardiac tamponade after emergency tensión-free repair of a large paraesophageal hernia. Surg Endosc 2000; 14: 593. [ Links ]

32. Granderath FA, Kamolz T, Schweiger UM, Pointner R. Laparoscopic refundoplication with prosthetic hiatal closure for recurrent hiatal hernia after primary failed antireflux surgery. Arch Surg 2003; 138: 902-7. [ Links ]

33. Novell J, Targarona EM, Vela S, Cerdán G, Bendahan G, Torrubia S, et al. Resultados a medio plazo y calidad de vida del tratamiento laparoscópico de la hernia de hiato paraesofágica. Cir Esp 2004; 76(6): 382-7. [ Links ]

34. Parameswaran R, Ali A, Velmurugan S, Adjepong SE, Sigurdsson A. Laparoscopic repair of large paraesophageal hiatus hernia: quality of lile and durability. Surg Endosc 2006; 20(8): 1221-4. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Alberto Pagán Pomar.

Servicio de Cirugía General. Hospital Universitario Son Dureta.

C/ Andrea Doria, 55. 07014 Palma Mallorca.

e-mail: ajpagan@telefonica.net

Received: 22-12-08.

Accepted: 15-01-09.

texto en

texto en