Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.102 no.2 Madrid feb. 2010

Whipple's disease in Spain: a clinical review of 91 patients diagnosed between 1947 and 2001

Enfermedad de Whipple en España. Revisión clínica de 91 pacientes diagnosticados durante 1947-2001

E. Ojeda1, A. Cosme2*, J. Lapaza1, J. Torrado3†, I. Arruabarrena1 and L. Alzate2

1Department of Internal Medicine. Donostia Hospital. San Sebastián, Guipúzcoa. Spain. Departments of 2Digestive Diseases and 3Pathological Anatomy. Donostia Hospital. *CIBEREHD. University of the Basque Country. San Sebastián, Guipúzcoa. Spain.

ABSTRACT

Background: to determine the epidemiological, clinical, diagnostic and therapeutic characteristics of Whipple's disease in Spain.

Patients and method: cases of Whipple's disease reported in the Spanish literature between 1947 and 2001 which meet histological or PCR criteria are reviewed.

Results: 91 cases were included, 87.5% of which were male. The maximum incidence was between 40 and 60 years of age (68%). There was no family clustering or susceptibility by profession or surroundings. The most common symptoms and signs were: weight loss (80%), diarrhoea (63%), adenopathies (35%), skin problems (32%), abdominal pain (27%), fever (23%), joint problems (20%) and neurological problems (16%). Arthralgias, diarrhoea and fever were noted prior to diagnosis in 58, 18 and 13% of patients, respectively. Diagnosis was histological in all cases except two, which were diagnosed by PCR. Intestinal biopsy was positive in 94%. Adenopathic biopsies (mesenteric or peripheral) were suggestive in 13% of cases, and treatment was effective in 89%. There were nine relapses, four of which were neurological, although all occurred before the introduction of cotrimoxazole.

Conclusions: Whipple's disease is not uncommon, although it requires a high degree of suspicion to be diagnosed in the absence of digestive symptoms. The most common and most sensitive diagnostic method is duodenal biopsy. PCR is beginning to be introduced to confirm the diagnosis and as a therapeutic control. Initial antibiotic treatment with drugs that cross the blood-brain barrier, such as cotrimoxazole and ceftriaxone, is key to achieving a cure and avoiding relapses.

Key words: Whipple's disease. Clinical review. Spanish series (91 cases).

RESUMEN

Fundamento: conocer las características epidemiológicas, clínicas, diagnósticas y terapéuticas de la enfermedad de Whipple en España.

Pacientes y método: se revisan los casos de enfermedad de Whipple de la literatura española que cumplen criterios histológicos o de PCR desde 1947 hasta 2001.

Resultados: se incluyeron 91 casos. El 87,5% eran hombres. La incidencia máxima fue entre los 40 y 60 años de edad (68%). No hubo agregación familiar ni preferencia por profesión o entorno ambiental. Los síntomas y signos más habituales fueron: adelgazamiento (80%), diarrea (63%), adenopatías (35%), cutáneos (32%), dolor abdominal (27%), fiebre (23%), articulares (20%) y neurológicos (16%). Artralgias, diarrea y fiebre se referían previamente al diagnóstico en el 58, 18 y 13% de los enfermos, respectivamente. El diagnóstico fue histológico en todos salvo en dos que se diagnosticaron por PCR. La biopsia intestinal fue positiva en el 94%. Las biopsias de adenopatías (mesentéricas o periféricas) fueron orientadoras en un 13%. El tratamiento fue eficaz en el 89%. Hubo 9 recidivas, 4 neurológicas, estas antes de la introducción del cotrimoxazol.

Conclusiones: la enfermedad de Whipple no es tan infrecuente. Se precisa un alto índice de sospecha para diagnosticarla en ausencia de síntomas digestivos. El método diagnóstico más empleado y más sensible es la biopsia duodenal. Se empieza a introducir la técnica de PCR para confirmar el diagnóstico y como control terapéutico. El tratamiento antibiótico inicial con antibióticos que pasan la barrera hematoencefálica como cotrimoxazol y ceftriaxona es determinante para la curación de los pacientes y evitar las recidivas.

Palabras clave: Enfermedad de Whipple. Revisión clínica. Serie española (91 casos).

Introduction

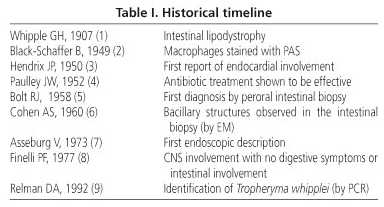

Whipple's disease (WD) is a chronic infection whose causative agent, Tropheryma whipplei, was identified in 1992. This disease affects the digestive tract, joints, lymph nodes, skin, heart, lungs, nervous system, eyes, liver, kidneys, haematopoietic system and other organs. George Hoyt Whipple described the first case of this disease in a 36-year-old medical missionary recently returned from Turkey who was admitted to Johns Hopkins hospital in 1907 (1). The patient was suffering from arthritis, weight-loss, low-grade fever and diarrhoea. The autopsy showed important involvement of the intestine and mesenteric nodes. Whipple termed this disease "intestinal lipodystrophy" as he considered that it was likely to be the result of a lipid metabolic disorder in light of the numerous fat deposits found in the intestinal lamina propria and mesenteric adenopathies. The most relevant discoveries concerning this disease are listed chronologically in table I (2-9). Between 1908 and 1949, 15 patients with symptoms consistent with WD were collected. In 1986, Dobbins (10) compiled 617 cases from the medical literature and a further 79 cases by correspondence. Of a total of 696 patients, 246 were from the USA, 114 from Germany and 91 from France. The total number of cases published in the last 100 years does not reach 2000.

In 1947, Oliver Pascual reported the first case of WD in Spain in the May-June issue of the Spanish Journal of Diseases of the Digestive Apparatus and Nutrition (11). This case involved a 34-year-old woman who had been suffering from weight loss, intermittent diarrhoea and abdominal pain for over 20 years. An anatomopathological study of the abdominal nodes through laparotomy confirmed the diagnosis, with mesenteric node lesions resulting from lipophagic granulomatosis. More than 100 cases have been reported in Spain to date.

Patients and method

A search for WD in the Spanish medical literature was performed for the period 1947 to December 2001 (11-84) using the MEDLINE database (Whipple's disease), conference and meeting proceedings and the Doyma database. Those patients who met histological or PCR criteria were included. Histology-positive was defined as: a greater or lesser degree of villous atrophy, infiltration of the lamina propria by mononuclear cells, and the presence of macrophages with vacuoles filled with fat and PAS-positive diastase-resistant granules. Rod-shaped bacillary intracellular structures observed by EM. Compatible histology: non-caseating granulomas, other pathologies ruled out, and response to antibiotics. These patients' clinical and epidemiological characteristics were analysed and four of our own patients who attended in the period 1994-2000 but whose cases were reported subsequently were included (12).

Results

The case material between the 1940s and 1970s is very limited (15 patients in 30 years), whereas since then, and up to the end of 2001, 72 cases (83% of the total) were published at an average of two or three a year (Fig. 1). Clinical data were obtained for 89 patients. Two of these were taken from specialised journals which only reported biopsy and endoscopic data. The treatment was clearly specified in 75 cases, five were not treated, as they had died, and no treatment was specified in a further 11 cases. The distribution by Autonomous Community is shown in figure 2. Seventy seven of patients were male (87.5%) and 11 female (12.5%); no sex was specified for three cases. The age extremes were 23 and 79 years, with a maximum incidence between the ages of 40 and 69 years (68% of the total). No age was reported in five cases, and there were no family cases.

The most frequent pre-diagnostic symptoms, defined as those present for more than three months before visiting the doctor, are listed in table II. Joint problems are the most common (52 cases), with 27 (56%) of these cases involving oligoarticular arthralgies, followed by mono- or oligoarticular arthralgies/arthritis (15 cases, 30%), polyarthritis (7 cases, 14%) and polyarthralgies (3 cases, 6%), one of which was migratory. The longest time interval between appearance of the symptoms and diagnosis was 20 years in one case of polyarthralgy, followed by six years in one case of polyarthritis. A majority were intervals of three to four years for monoarticular arthralgies/arthritis. Initial diagnoses were: palindromic rheumatism, gout, psoriatic arthritis, seronegative polyarthritis, and, in one case, HLA-B27-positive arthritis.

Chronic diarrhoea syndrome was present in 16 cases, although the time to progression was not specified. Abdominal pain was mentioned in 10 cases, with six of these involving diffuse pain, one localised epigastric pain and three recurring dyspeptic pain. Fever occurred prior to admission in 12 cases, with four of these cases being relapsing. The longest time interval from relapsing fever to diagnosis was 10 years, followed by a further three cases of seven, six and one year, respectively. One case was diagnosed several years previously as granulomatous dermatitis consistent with sarcoidosis, and another as leukocytosis with persistent anaemia. Three cases mentioned previous cardiac arrhythmia but in only one of these cases was first-degree AV block with bradycardia, presenting as syncope, specified.

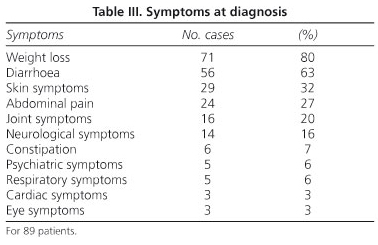

The symptoms at diagnosis are listed in table III. The most common are weight loss (80%) and diarrhoea (63%), which reached the stage of cachexia in six cases. The diarrhoea was accompanied by blood, either in the form of melena or haematochezia, in six cases. Cutaneous symptoms are next 29 cases, 32%, particularly hyperpigmentation (22 cases), on occasion together with scleroatrophic skin, which in a majority of cases is associated with severe malabsorption. There were five cases of purpura, one subcutaneous nodule and one macular rash. Three of the purpura cases appeared to be related to vitamin K-dependent factor deficiency, whereas the other two had vasculitis, which was leukocytoclastic in one case and allergic in the other. The histology of the case with the subcutaneous nodule in the forearm showed this nodule to be "rheumatoid".

Abdominal pain was mentioned upon admission by 24 patients (27%), a majority as abdominal distension. This was associated with diarrhoea in 17 cases (18%). When this pain was localised, in seven cases it was described as epigastric, in one as digestive fullness, in one in the left hypochondrium, another on the left flank, and two in the mesogastrium. Other digestive symptoms included constipation in six cases and vomiting in three. Digestive symptoms were absent in 15 patients (17%). The joint symptoms present at diagnosis included peripheral asymmetric polyarthralgia (7 cases), with one case of arthromyalgia. A further six patients had monoarticular arthritis, usually in the knees and ankles and occasionally in the hands. Two cases had acropachy and one was diagnosed of synovitis.

The most frequent neurological symptom was a greater or lesser degree of consciousness disorder, most often loss of space-time awareness and the ability to concentrate (8 cases). Memory loss was reported in three cases, with dementia in one and ataxia in four more. A restricted ability of vertical gaze compatible with supranuclear ophthalmoplegia was present in three cases, with loss of strength and lower limb pain in four cases and dysarthria in a further two. Hemiparesia was present in one case, lymphocytic meningitis in another, cephalea in one other and facial myoclonus with tonic mandibular contractions in yet another. Two patients presented nystagmus. Neurological symptoms were the reason for admission in four cases, in two these were non-exclusive protagonists, and in a further two WD was limited to the nervous system. Other symptoms were the reason for admission in 10 cases and relapse modality in four. Psychiatric alterations consisted of apathy alternating with irritability in two cases and depressive syndrome in a further two. Insomnia was mentioned as clinically relevant in one case. Three patients had dyspnea due to heart failure, and two due to pleuropulmonary involvement. Dry cough was present as a key and persistent clinical symptom in three cases. Ocular symptoms such as blurred vision and eye pain were present in three cases.

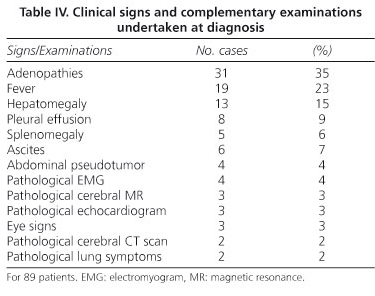

The signs visible at diagnosis and the complementary pathological examinations are listed in table IV. A large number of patients (31) had adenopathies, which were peripheral, palpable, cervical and/or axillary in 16 cases, non-palpable in 15 cases, abdominal (mesenteric, paraaortic or mesenteric-caval) in 14 cases, hilar in one case, and mediastinalc/abdominal in another case. Fever was persistent, equal to or higher than 38 ºC, relapsing in four cases and low-grade in five. Two of the five patients with splenomegaly also had hepatomegaly. Pleural effusion was bilateral in six cases, unilateral in two, and massive in one. Pericardial effusion was small in three cases and huge in another. A further case was found during autopsy. Six patients presented with ascites. E. coli was isolated from the ascitic fluid of one of these patients. Ocular signs were one case of papilledema (patient with no neurological symptoms), one with anterior uveitis, and one with recurring conjunctivitis. Chest X-rays showed a bilateral interstitial pulmonary pattern in one case, and dense patchy regions in the right lung in another. EMG showed peripheral sensory-motor polyneuropathy in two cases, and myopathy in two more patients. Two echocardiograms showed slight pericardial involvement and one was compatible with cardiomyopathy. Brain CT scans were interpreted as showing multistroke encephalopathy in one case and cortical-subcortical atrophy with marked hydrocephaly in another. Three brain MRI scans were performed, one of which showed cortical-subcortical atrophy, another predominantly subcortical cerebral atrophy with lacunae indicative of an old sub-occlusive pathology in the subcortical white matter, and the other hyperdense regions in T2 in both temporal lobes.

Laboratory data reported at diagnosis are limited and of little use. The most common are those related to malabsorption (hypoproteinaemia and anaemia, usually with sideropenia). Increased sedimentation rate was noted in only four cases, hypergammaglobulinaemia in two (polyclonal in one), and an increase in IgA and IgM in another. Hypogammaglobulinaemia was only noted in one case. One patient presented alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, another was HLAB27-positive and another hepatitis B antigen-positive.

The diagnostic methods used are listed in table V. Diagnosis was histological in 89 cases and PCR-based in two. The most common diagnostic technique used was intestinal biopsy, particularly jejunal until 1980, with a peroral capsule. After 1990, biopsies were mainly taken from the second portion of the duodenum by gastroscopy due to its ease of use and greater efficacy. Biopsies were taken from both sites in four cases. Of all 86 intestinal biopsies, the sample was normal in the presence of disease in five cases, two were diagnosed by PCR, one during autopsy with disease limited to the brain, one with CNS WD diagnosed by brain biopsy and another upon study of the spleen after splenectomy; all were confirmed by EM. Intestinal biopsy was also performed to confirm biopsy findings from other sites (three retroperitoneal or mesenteric adenopathy biopsies and four peripheral adenopathy biopsies, indicative of post-lymphographic WD compatible with sarcoidosis and chronic non-specific inflammation, respectively). A liver biopsy was performed along with an intestinal biopsy during laparotomy in three cases. One of these showed histiocytic granulomas, another indicated "granulomatous hepatitis", and the other active chronic hepatitis with hepatitis B surface antigen. The gastric biopsy performed along with duodenal biopsy in four cases was suggestive of WD in two of them, with one of the others indicating chronic atrophic gastritis and the other being normal. A subsequent colon biopsy has also been used to confirm the diagnosis from duodenal biopsy. Sarcoidal granulomas were found in five cases, one in the oesophagus, another in a supraclavicular adenopathy, another one in the skin several years before and two in liver biopsies. Only one of these had been diagnosed previously as sarcoidosis.

Electron microscopy was performed in 26 cases. Brain biopsy was performed using the stereotactic technique. Laparotomy was used to obtain biopsy samples in four cases, and autopsy permitted a diagnosis in two. In one of these WD was limited to the brain, whereas in the other the oesophagus, intestine, lungs, liver, spleen, bone marrow and heart were also affected.

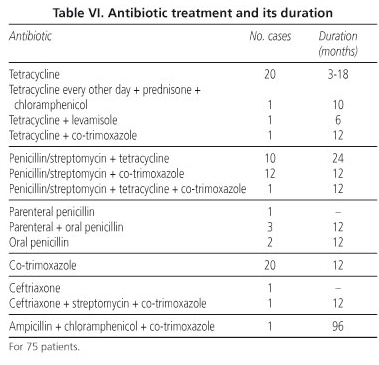

The treatment is listed in table VI. This initially involved tetracyclines at a dose of 1 g/day, except for two patients who received 2 g/day and one who received an alternate regimen for a period of between three months (followed by oral cotrimoxazole) and one year. Penicillin at a dose of 1,200,000 U/day and streptomycin at 1 g/day for two weeks, followed by tetracyclines for a period of between six months and one year, was started in 1978. Co-trimoxazole treatment (800/160 every 12 hours) was introduced in 1987. In the majority of cases this was given after the initial penicillin/streptomycin treatment, although more recently it is given as a monotherapy from the outset. The initial improvement is similar with any of the above regimens and can first be seen after the first six or seven days up to around two to three weeks, with clinical cure being achieved in two to three months. Length of treatment was reported in 64 cases, lasting for a year or more in 49 of them. The longest treatments were eight, six and three years, the former two due to neurological problems and the third due to persistent abdominal pain. Control biopsies were performed in 35 cases (11 jejunal and 24 duodenal). A jejunal biopsy was performed up to 1980 at between one and six months after treatment onset in the event of persistent, although less intense, histological image and clinical improvement. Duodenal biopsy was still pathological when performed within the first six months in 10 cases (41%) and between six months and one year in six (25%). Histiocytic isolates persisted at four years in one case. An EM study was performed in six cases and PCR controls in two.

Long-term follow-up is only mentioned in 38 cases: in one up to 9.5 years, in three up to eight, one up to seven and 33 up to a year and a half. Nine relapses have been reported, four involving the CNS (one at three months, one at 10 months, one after one year and another after two), and three involving recurring intestinal symptoms: one of these suffered three relapses at 14, 28 and 40 months, and another two relapses at 24 and 36 months, all of which were digestive. The other relapse had the appearance of multiple subcutaneous nodules at three months. The treatment regimen followed by most relapses was tetracycline as single antibiotic (five of the nine), which was fatal). Co-trimoxazole was related to two relapses, one digestive and one cutaneous (Table VII). The other relapse occurred due to therapy discontinuation.

Discussion

The analysis of incidence by Autonomous Community shows the highest incidence in Andalusia, followed by Madrid, Catalonia and the Basque Country. However, as similar trends are not found in neighbouring communities, this is more likely to reflect the interest by certain hospitals in pursuing this diagnosis rather than a geographic susceptibility to the disease.

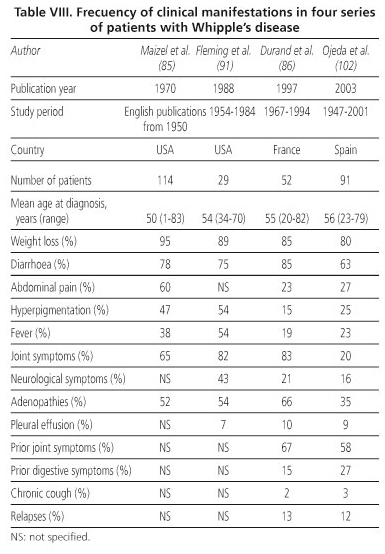

The most characteristic symptoms of WD in this series are: weight loss, diarrhoea, hyperpigmentation, abdominal pain and fever, in that order (85,86). Onset with diarrhoea is not, however, as common in the Spanish series as in another two series in the literature (Table VIII). The series described by Durand et al. (86) and that described herein are similar in terms of abdominal pain, hyperpigmentation and fever. The "driest" cases, in other words those with no digestive symptoms or even constipation, are also found in this series, which means they require a higher degree of suspicion of this disease. Diffuse abdominal pain appears to be related to distension and inflammation of the jejunal loops, except for patients with ascites. Pain in the left hypochondrium was mentioned by a patient with hepatosplenomegaly, possibly due to distension of the spleen's capsule. The two cases involving the mesogastrium were probably due to distension of the intestinal loops as the mesenteric adenopathies were very small. As the adenopathies were smaller than one centimetre, they were also unlikely to be responsible for the other case of abdominal pain, which showed radiological signs of intestinal subocclusion. The abdominal pseudotumor appears to be related to an increase in mesenteric adenopathies.

Adenopathies were found in over one third of patients and were also very common (52%) in the series by Maizel et al. (85) Peripheral adenopathies facilitate histological studies which, although only a guide, can rule out other processes and allow a differential diagnosis to be established. This, however, does not remove the need for a duodenal biopsy and/or PCR study of the sample to confirm WD. If nodal symptoms are abdominal, the patients in this and the other series were biopsied by laparotomy for suspected lymphoma. However, in published WD cases with primary nodal involvement, the symptoms indicative of this disease described in the clinical history and preceding conditions should have suggested a duodenal biopsy, thus avoiding the need for laparotomy (87). Fever was not present as an isolated symptom in any case at diagnosis, although in some cases it was the only symptom for many years previously, with the longest period being 10 years, followed by others of seven, six and one year.

Regarding neurological symptoms, only one patient exhibited the classic triad of dementia, ophthalmoplegia and myoclonus. This patient also had a symptom considered to be pathognomonic, namely oculomasticatory myoclonia. Macrophage infiltrates in the CNS are usually located in the periependymal region and the subcortical white matter, with a good clinical-radiological correlation (88). Vascular involvement, with arteritis and thrombosis, is much less common. In contrast to the other two series (85,86), the number of patients in this series with joint symptoms at diagnosis was not high, although it was high as a preceding condition. All such cases were peripheral arthropathies; none were axial. The delay in diagnosis, upon taking into account these previous joint symptoms, was around four years.

The irritative cough presented by one of the cases, which persisted for two months, is not common, although Whipple described such a symptom in his first patient. This symptom has been reported to occur in up to 50% of a series of 15 patients (89), although larger studies make no mention of it. Thus, only one of the 52 patients in Durand et al.'s series (86) had chronic cough as a preceding condition. The possible causes of this symptom include pleural effusion (72% of patients with chronic cough were found to have pleural effusion at autopsy) or pulmonary infiltration -lung biopsy suggested the diagnosis, which was subsequently confirmed, in cases with severe chronic cough and absence of gastrointestinal symptoms (90).

There were several cases of dyspnea due to heart failure with cardiomyopathy, ischaemic cardiopathy or vascular involvement which may be secondary to WD in the Spanish study. There was no case of endocarditis. Initial heart failure is uncommon and could be due to the involvement of any of the heart's three layers or coronary arteries. Endocarditis is found in up to 30% of WD cases (91), a figure which rises to around 50% in post-mortem studies. The pericardium was found to be affected during autopsy, in the absence of symptoms, to an even greater extent than the pleura (up to 79%). This is due to adhesive constrictive pericarditis. Myocardial involvement is suspected on the basis of changes in the ECG and echocardiographic results compatible with cardiomyopathy (92), some of which can be reversed with antibiotic treatment. In these cases, a lack of digestive symptoms means that diagnosis is very difficult unless faced with a cardiac relapse in a patient already diagnosed with WD. The diagnosis is normally reached by studying a valve which has been replaced or, more rarely, by endomyocardial biopsy due to suspected myocarditis (93).

The diagnosis of this disease is still based on a histological study of the small intestine, particularly the duodenal mucosa. Digestive symptoms upon admission suggest a need for a jejunal or duodenal biopsy, which allows a correct diagnosis to be reached more rapidly. The differential diagnosis most often proposed when faced with a combination of digestive and constitutional symptoms is either abdominal neoplasia or lymphoma, therefore a biopsy is performed relatively rapidly. Additional hyperpigmentation is also indicative of malabsorption and also suggests an initial intestinal study. When fever is present along with toxic or constitutional syndrome, it is not unusual to start the protocol for a fever of unknown origin once infection has been ruled out. Diagnosis can be made by only examining the histologic samples of digestive mucosa under an optical microscope without need for confirmation by identifying bacillary shapes under electron microscope or PCR -Dobbins (10)-. The sensitivity of this test when findings are those defined as characteristic, irrespective of whether the biopsy sample is jejunal or duodenal, is 94%. The sensitivity for a gastric biopsy is lower and that for a rectal or colonic biopsy much lower as a large number of normal people can present histiocytes in the lamina propria of the mucosa at these sites; it could even be due to a histiocytic colitis. Confirmation by electron microscopy with duodenal biopsy, or by PCR, is required in such cases. Specificity, which is high to start with, increases to 100% if electron microscopy or PCR results are positive.

The finding of appropriate histological characteristics in the jejunal or duodenal biopsy only leads to a differential diagnosis in this situation when "pseudo-Whipple" is suspected in HIV patients. This disease is caused by Mycobacterium avium and can easily be ruled out, particularly if the patient has a history of HIV exposure.

Histoplasmosis, malacoplakia and Waldenström's ma-cro-globulinaemia would be suggested by specific epidemiological, clinical, biochemical and immunological data. If the histological results from the biopsy of the small intestine show non-caseating or sarcoidal granulomas, a differential diagnosis should be performed with intestinal tuberculosis and sarcoidosis. In this case it should be found at other, more typical sites, and if this is not the case, the diagnosis should be checked periodically as sarcoidosis can be diagnosed several years before WD. The bacillus has been identified by PCR in the cerebrospinal fluid (94), synovial fluid and/or tissue (95), pleural fluid (96), vitreous humour (97), peripheral blood mononuclear cells (96), and in faeces (98). Its value is, however, only confirmatory or for control of the disease, not diagnostic.

Treatment should involve an antibiotic which passes easily across the blood-brain barrier, such as: intravenous ceftriaxone (2 g day) for 15 days, followed by oral sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (800/600) every 12 h, or oral cefixime (400 mg a day) up to one year (99), or sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (800/160), first parenterally for two weeks and then orally for up to at least a year. Other antibiotics such as rifampicin and chloramphenicol have proven useful in allergics, for example, to betalactams and sulfamides. Immunotherapy with gamma interferon has been used in cases refractory to antibiotic treatment (100,101).

Histological studies show no relation to clinical symptoms, and in many cases the lesions persist for more than a year, although bacillary formations are not observed by electron microscopy. An increase in CD58 levels could be useful for defining disease activity and length of treatment, although this is still just a hypothesis. PCR is a good control method, and an immunofluorescence-based antibody assay could be so in the future. However, the most reasonable approach thus far in the absence of a specific biochemical marker for activity is to maintain treatment while histological findings persist. An endoscopic duodenal biopsy should therefore be taken annually for the first five years after diagnosis, along with PCR if possible. If there is no intestinal involvement, the test which led to the diagnosis should be repeated, together with an electron microscopic or PCR study. Treatment should never last less than one year, and should be at least two years in cases with neurological or cardiac involvement. Follow-up should last for at least 10 years.

Relapses should be treated in the same way as the initial disease. Outcomes were good in the current series except for one patient who died from neurological relapse. Relapse frequency was 12% (102), similar to that reported by Durand et al. (86) (13%) and much lower than that reported in the English literature (35%) (103), probably due to the fact that the latter data were obtained when cotrimoxazole was not used as widely as it is now.

References

1. Whipple GH. A hitherto undescribed disease characterized anatomically by deposits of fat and fatty acids in the intestinal and mesenteric lymphatic tissues. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp 1907; 18: 382-91. [ Links ]

2. Black-Schaffer B. Tinctorial demostration of glycoprotein in Whipple's disease. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1949; 72: 225-7. [ Links ]

3. Hendrix JP, Black-Schaffer B, Withers RW, Handler P. Whipple's intestinal lipodystrophy: report of 4 cases. Arch Inter Med 1950; 85: 91-131. [ Links ]

4. Paulley JW. A case of Whipple's disease (intestinal lipodystrophy). Gastroenterology 1952; 22: 128-33. [ Links ]

5. Bolt RJ, Pollard HM, Standaert L. Transoral-bowel biopsy as an aid in the diagnosis of malabsorption states. N Engl J Med 1958; 259: 32-4. [ Links ]

6. Cohen AS, Schimmel EM, Holt PR, Isselbacher KJ. Ultrastructural abnormalities in Whipple's disease. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1960; 105: 411-4. [ Links ]

7. Asseburg V, Kienecker B, Manitz G. Melaena bei M. Whipple. Z Gastroenterologie 1973; 11: 547-9. [ Links ]

8. Finelli PF, McEntee WJ, Lessel S, Morgan TF, Copetto J. Whipple's disease with predominantly neuroophtalmic manifestations. Ann Neurol 1977; 1: 247-52. [ Links ]

9. Relman DA, Schmidt TM, MacDermott RP, Falkow S. Identification of the uncultured bacillus of Whipple's disease. N Engl J Med 1992; 327: 293-301. [ Links ]

10. Dobbins WO III. Whipple's disease. Springfield (IL): Charles C Thomas; 1987. [ Links ]

11. Oliver Pascual E, Galan J, Oliver Pascual A, Castillo E. Un caso de lipodistrofia intestinal con lesiones ganglionares mesentéricas de granulomatosis lipofágica (enfermedad de Whipple). Rev Esp Ap Dig y Nutr 1947; 6: 213-26. [ Links ]

12. Ojeda E, Cosme A, Lapaza J, Torrado J, Arruabarrena I, Alzate L. Manifestaciones infrecuentes de la enfermedad de Whipple. Estudio de cuatro casos. Gac Med Bilbao 2005; 102: 75-9. [ Links ]

13. Bergareche J. Enfermedad de Whipple. Rev Esp Ap Dig y Nutr 1947; 6: 234-40. [ Links ]

14. Jiménez Díaz C, G Mógena H, Valle A, Oliva H, Navarro Y. Estudio clínico, histológico y ultramicroscópico de un caso de enfermedad de Whipple antes y después del tratamiento con aureomicina. Rev Clin Esp 1964; 92: 229-42. [ Links ]

15. García-Conde Gómez F, Llombart Bosch A, García-Conde Bru FJ, Aparisi Quesada L, Peydro Olaya A, Palao Esteve SJ. Enfermedad de Whipple: clínica, morfología y ultraestructura de un caso. Rev Esp Enf Ap Dig 1970; 30: 373-404. [ Links ]

16. Oliva Adámiz H, González Campos C, Navarro Berástegui V, González Mogena H. Enfermedad de Whipple: hallazgos microscópicos, ópticos y electrónicos en dos enfermos controlados durante uno y ocho años. Bol Fund Jiménez Díaz 1971; 3: 373-86. [ Links ]

17. Vázquez Rodríguez JJ, Segura A, Silva Pozo J, López Serrano C, Villamor J. Enfermedad de Whipple y papiledema. Rev Clin Esp 1971; 123: 381-8. [ Links ]

18. Pérez Carnero A, Miño Fugarolas G, Gutiérrez Molina M, Muro J. Enfermedad de Whipple. Un nuevo caso. Rev Esp Enf Ap Dig 1972; 37: 777-90. [ Links ]

19. Rodrigo Sáez L, Alonso González JL, Riesgo Miranda MA, Arribas Vizan A, Herrero Zapatero A, Arribas Castrillo JM. Rev Esp Enf Ap Dig 1976; 47: 359-72. [ Links ]

20. Domínguez Macías A, Fernández Pascual J, Pérez Gómez B, González del Castillo J, Cabello Otero A. Nuevos aspectos clínico-morfológicos de la enfermedad de Whipple. Rev Clin Esp 1976; 143: 253-64. [ Links ]

21. Gil Lita R, Almenar Royo V, Brotons Brotons B, Reinoso JG, Grimactav JL. Contribución endoscópica al diagnóstico de la enfermedad de Whipple. Rev Esp Enf Ap Dig 1978; 54: 607-18. [ Links ]

22. López Lagunas I, Escribano Sevillano D, Rodrigo Sáez L, García J, Arroyo de la Fuente F, Mosquera JA. Presentaciones atípicas de la enfermedad de Whipple. Med Clin (Barc) 1978; 70: 379-83. [ Links ]

23. Pajares JM, Zaforas M, García Grávalos R, Gómez C, Torralba J. Lipodistrofia intestinal (enfermedad de Whipple). Aspectos evolutivos y terapéuticos en un caso seguido durante siete años. Gastroenterol Hepatol 1979; 2: 86-91. [ Links ]

24. Sánchez Alcalá B, Marfil Lizana JM, Montero García M, Bermúdez García JM, Peña Angulo JF, Linares Solano J. Enfermedad de Whipple. Estudio clínico, inmunológico, histológico y ultraestructural de un nuevo caso. Gastroenterol Hepatol 1979; 2: 82-5. [ Links ]

25. Muñoz M, Rodríguez JL, Varela JI, Franquet T, Conchillo F. Métodos endoscópicos y biópsicos sencillos para el estudio diagnóstico y evolutivo de la enfermedad de Whipple. 1ª Jornada Nacional de Endoscopia Digestiva (Asociación Española de Endoscopia Digestiva). Casos FLASH. Barcelona; 1979; 51-5. [ Links ]

26. Solís Herruzo JA, González Sanz-Agero P, Garzón Martín A, Navas Palacios JJ. Enfermedad de Whipple. Aspectos clínicos, endoscópicos y ultraestructurales de un nuevo caso. Gastroenterol Hepatol 1980; 3: 236-40. [ Links ]

27. Cabarcos A, Neira F, Muñoz A, Sellarés R, Zabalza R, Damiano A. Enfermedad de Whipple. Presentación de un nuevo caso y análisis de los 16 publicados en nuestro país. Rev Clin Esp 1982; 167: 169-73. [ Links ]

28. Martín Herrera L, Díaz García F, Moreno Gallego M. Utilidad de la duodenoscopia en el diagnóstico de la enfermedad de Whipple. Gastroenterol Hepatol 1982; 5: 205-8. [ Links ]

29. Zozaya JM, Muñoz M, Sánchez L, Ruiz R, Pardo J, Conchillo F. Utilidad de la endoscopia en el diagnóstico de la enfermedad de Whipple. A propósito de dos nuevos casos, sin clínica de diarrea. V Jornada Nacional de Endoscopia Digestiva. Santander; 1983; 89-95. [ Links ]

30. Rigau J, Piqué JM, Rives A, Navarro S, Bonet J. Forma de presentación anómala de la enfermedad de Whipple. Gastroenterol Hepatol 1983; 6: 480-83. [ Links ]

31. Condomines J, Rives A. Varón de 42 años con fiebre, pérdida de peso y malabsorción. Med Clin (Barc) 1985; 85: 846-54. [ Links ]

32. Rodríguez S, García F, López JM, Basterra G, Zabaleta S, Merino A. Correlación de los hallazgos endoscópicos e histológicos en la enfermedad de Whipple. Rev Esp Enf Ap Dig 1985; 67(Supl. 1): 50-1. [ Links ]

33. Casellas F, Lirola JL, Vargas V. Síndrome tóxico y enfermedad de Whipple. Med Clin (Barc) 1986; 86: 480-1. [ Links ]

34. Obrador A, Gaya J. A propósito de dos casos de enfermedad de Whipple. Diagnóstico diferencial del duodeno blanco. Rev Esp Enf Ap Dig 1986; 69(Supl. 1): 88-9. [ Links ]

35. Carballo C, Diéguez P, Murias E, Pérez E, Lado F, Rodríguez L. Enfermedad de Whipple asociada a depósitos hepáticos de alfa-1-antitripsina (fenotipo PiMS) y melenas. Rev Esp Enf Apar Dig 1986; 70: 443-7. [ Links ]

36. Garza F, González P, Suárez JM, Mora P, Castro F, Muro J. Un nuevo caso de enfermedad de Whipple con afección gástrica y de intestino delgado. Rev Esp Enferm Apar Dig 1986; 69: 577-82. [ Links ]

37. Garza E, González P, Suárez JM, Mora P, Muro J, Santamaría P. Estudio comparativo de cuatro casos de enfermedad de Whipple diagnosticados en nuestro hospital. An Med Interna (Madrid) 1987; 4: 38-43. [ Links ]

38. Sala M, Colomer J, Cruceta A, Drudis T. Diagnóstico de la enfermedad de Whipple por fibrogastroscopia y biopsia duodenal. Med Clin (Barc) 1987; 89: 348. [ Links ]

39. Mateo JM, De Fuentes L, Rivero N, Ruiz JM. Enfermedad de Whipple. Revisión a propósito de un caso. Rev Esp Enf Apar Dig 1987; 71: 529-33. [ Links ]

40. Mur Villacampa M. Presentación inusual de la enfermedad de Whipple. Rev Esp Enferm Apar Dig 1987; 72: 183. [ Links ]

41. Pascual D, Sola R, Padrol C, Altadilla A, Prats A. Enfermedad de Whipple. Presentación atípica y diagnóstico endoscópico. Asociación Española de Endoscopia Digestiva. IX Jornada Nacional de Endoscopia Digestiva. Sevilla; 1987; 47-50. [ Links ]

42. Fábrega E, Condomines J, Sainz S, Vila M, Such J, Roca M. Diagnóstico por biopsia e imagen endoscópica sugestiva de enfermedad de Whipple. Asociación Española de Endoscopia Digestiva. IX Jornada Nacional de Endoscopia Digestiva. Sevilla; 1987; 71-4. [ Links ]

43. Arcos R, García MD, Collantes E, Angulo R, Cisnal A, Martínez FG. Manifestaciones osteoarticulares de la enfermedad de Whipple: a propósito de tres casos. Rev Esp Reumatol 1987; 14: 94-6. [ Links ]

44. Ojeda E, Redondo J, Lapaza J, Ruiz I, Alzate LF. Enfermedad de Whipple: manifestaciones neurológicas y revisión de los casos publicados en la literatura nacional. Rev Clin Esp 1988; 183: 365-7. [ Links ]

45. Ruiz Montes F, Puig Ganau T, Reñé Espinet JM, Rubio Caballero M. Enfermedad de Whipple: revisión de la literatura española, comparación con la literatura internacional y aportación de un nuevo caso. Rev Esp Enf Apar Dig 1988; 74: 679-85. [ Links ]

46. Colomer J, Miguel JM, Sala M, Drudis T. Utilidad de la endoscopia en el diagnóstico y evolución de un caso de enfermedad de Whipple. Asociación Española de Endoscopia Digestiva. X Jornada Nacional de Endoscopia Digestiva. Toledo; 1988; 55-8. [ Links ]

47. Domínguez F, Saus C, Boixeda D, Fernández C, Gil LA, Meroño E. Enfermedad de Whipple: aspectos endoscópicos y utilidad de la biopsia endoscópica en el diagnóstico y seguimiento. Gastroenterol Hepatol 1989; 12: 33-5. [ Links ]

48. Conde García FJ, Larraona Moreno JL, Vicioso Recio L, Suárez Lozano I. Granulomas hepáticos en el curso de una enfermedad de Whipple. Gastroenterol Hepatol 1989; 12: 129-32. [ Links ]

49. Yañez J, Vázquez JL, Suárez F, Alonso P, Durana J, Gómez M. Enfermedad de Whipple con remisión de imágenes endoscópicas e histológicas tras tratamiento. Asociación Española de Endoscopia Digestiva. XI Jornada Nacional de Endoscopia Digestiva. Granada; 1989; 183-8. [ Links ]

50. Carballo Fernández C, Murias Taboada E, Cutrin Prieto C, Pérez Becerra E, Lado Lado F, Rodríguez López I. Enfermedad de Whipple y esplenomegalia con biopsias intestinales negativas. Rev Esp Enf Apar Dig 1989; 75: 397-400. [ Links ]

51. Gratacós J, Del Olmo A, Peris P, Muñoz-Gómez J. Enfermedad de Whipple. Diagnóstico temprano a través de la patología articular. Med Clin (Barc) 1990; 94: 396-7. [ Links ]

52. Gea F, Rábago L, Martín L, Eroles G, Paniagua C, Montiel P. Enfermedad de Whipple. Diagnóstico endoscópico. Asociación Española de Endoscopia Digestiva. XII Jornada Nacional de Endoscopia Digestiva. Reus; 1990; 85-8. [ Links ]

53. Pérez Sola A, González Martín JA, Razquin J, Calderón Rodríguez J, Peiro Callizo ME, Martínez Montiel MP. Enfermedad de Whipple: un nuevo caso. Aspectos videoendoscópicos evolutivos. Asociación Española de Endoscopia Digestiva. XII Jornada Nacional de Endoscopia Digestiva. Reus; 1990; 91-5. [ Links ]

54. Cardellach F, Moragas A. Fiebre, erupción cutánea, artralgias y uveítis en un varón de 50 años. Med Clin (Barc) 1991; 96: 549-57. [ Links ]

55. Antón Botella F, Yangüela Terroba JM, Simón Marco MA, Ruiz Valverde A, Olagaray Ibáñez JL. Enfermedad de Whipple con afectación gástrica y duodenal. Un nuevo caso. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 1991; 79: 143-6. [ Links ]

56. Hidalgo Rojas L, Fernández de la Puebla Jiménez RA, Villanueva Marcos JL, Montero Pérez-Baquero, M. Enfermedad de Whipple manifestada como síndrome tóxico y adenopatías abdominales. Med Clin (Barc) 1991; 96: 788. [ Links ]

57. Lanzas MG, Acha V, Burusco MJ, Tiberio G. Síndrome tóxico y mialgias como manifestación de una enfermedad de Whipple. An Med Interna (Madrid) 1991; 8: 625-6. [ Links ]

58. Antón Aranda E, Sacristán Torroba B, Martín Cabane J. Valor de la fibrogastroscopia y biopsia en el diagnóstico y control evolutivo de la enfermedad de Whipple. An Med Interna (Madrid) 1991; 8: 366. [ Links ]

59. Díaz Lobato S, González Ruiz JM, Granado S, Bolado PR, García Talavera I, Pino JM. Sarcoidois y enfermedad de Whipple: ¿asociación o relación? Rev Clin Esp 1992; 190: 184-6. [ Links ]

60. Prada JIR, Balado MG, Alonso P, Yánez J, Suárez P, de Castro ML. Coloración vital en la enfermedad de Whipple. Revisión del cuadro clínico después del tratamiento con TMP-SMX durante tres meses. Asociación Española de Endoscopia Digestiva. XIV Jornada Nacional de Endoscopia Digestiva. Burgos; 1992; 229-35. [ Links ]

61. De la Peña J, De las Heras G, Martín Ramos L, López Arias MJ, Casafont F, San Miguel G. Diagnóstico endoscópico de la enfermedad de Whipple. XV Jornada Nacional de la Asociación Española de Endoscopia Digestiva. Libro de resúmenes. Cádiz; 1993; 30-1. [ Links ]

62. Sola Alberich R, Martínez Araque MJ, Pascual Torres D, Alonso Villaverde C. Granulomas periféricos seudosarcoidóticos: una manifestación de la enfermedad de Whipple. Med Clin (Barc) 1993; 101: 79. [ Links ]

63. Pallarés Manrique H, García Montes JM, Sánchez-Gey Venegas S, Pellicer Bautista F, Herrerías Gutiérrez JM. Síndrome constitucional y alteración del ritmo intestinal. Rev Clin Esp 1994; 104: 370-1. [ Links ]

64. Cruz Díaz M, Pitti Reyes S, Comas Serrano V, Rodríguez Torres J, Toledo Trujillo F. Enfermedad de Whipple. A propósito de un caso. Radiología 1994; 36: 394-6. [ Links ]

65. Ortiz Cansado A, Márquez Velásquez L, Maciá Botejara E, Marín Antúnez A, Cordero Torres R, Solana Lara M. Varón con demencia de aparición brusca asociada a diarrea de larga evolución, como manifestaciones de la enfermedad de Whipple. Gastroenterol Hepatol 1995; 18: 369-71. [ Links ]

66. Vigueras I, Mora A, Jordán A, Bonilla F. Insuficiencia cardiaca como manifestación inicial de la enfermedad de Whipple. Med Clin (Barc) 1995; 105: 158. [ Links ]

67. Gisbert JP, Martín Scapa MA, Álvarez Baleriola I, Moreida Vicente V, Hernández Ranz F. Diarrea, síndrome constitucional y artralgias. Rev Clin Esp 1995; 195: 657-8. [ Links ]

68. Guilera M, Rodríguez de Castro E, Solé J, Rezola J, Benet JM, Matos M. Seudotumor abdominal y enfermedad de Whipple. Gastroenterol Hepatol 1996; 19: 247-9. [ Links ]

69. Jiménez Palop M, Blázquez García MT, Manso Garzón C, Corteguera Coro M, Carbonero Díaz P. Artritis intermitente de larga evolución, como presentación de enfermedad de Whipple. Rev Esp Reumatol 1996; 23: 276-8. [ Links ]

70. Gómez de la Torre R, Claros González II, López Muñiz C, Velasco Álvarez A. Enfermedad de Whipple. Diagnóstico temprano a través de patología articular e hiperpigmentación. An Med Interna (Madrid) 1998; 15: 33-5. [ Links ]

71. García Castaño J, Del Toro Cevera J, Gómez Antúnez M, Farfán Sedano AI. Un nuevo caso de enfermedad de Whipple. An Med Interna (Madrid) 1998; 15: 509. [ Links ]

72. Lizarralde E, Martínez P, Tobalina I, Capel AL, Miguel F. Enfermedad de Whipple y anemia ferropénica. Gaceta Médica de Bilbao 1998; 95: 22-3. [ Links ]

73. Burguera M, Ibáñez MT, Bonal JA, Martí-Viaño JL, Cuesta A, Andrades E. Diagnóstico de enfermedad de Whipple en un enfermo ingresado en reanimación con sospecha de shock hipovolémico. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim 1999; 46: 47-8. [ Links ]

74. Zapatero Gaviria A, Ruiz Galiana J, Bilbao Garay J, Villanueva Sánchez J. Varón de 60 años con síndrome constitucional, dolor abdominal e insuficiencia cardiaca (sesión clínica cerrada). Rev Clin Esp 1999; 199: 310-20. [ Links ]

75. García JA, Martínez-Berganza A, Boldova R, Marín A, Laclaustra M, de los Mártires I. Hemorragia digestiva baja y enfermedad de Whipple: a propósito de un caso. An Med Interna (Madrid) 1999; 16 (Supl. 1): 91. [ Links ]

76. González MA, Gómez D, Madruga JI, Fernández F, Solera JC, Martín F. Enfermedad de Whipple. An Med Interna (Madrid) 1999; 16 (Supl. 1): 92. [ Links ]

77. Cadenas F, Sánchez-Lombraña, JL, Pérez R, Lomo FJ, Madrigal Rubiales, B, Vivas S, et al. Leucocitosis persistente como debut de la enfermedad de Whipple con desarrollo de cáncer gástrico en el seguimiento. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 1999; 91: 785-8. [ Links ]

78. Espinosa MD, Gila A, Medina T, Alché F, Muñoz J, García A, et al. Enfermedad de Whipple de presentación inusual. XXX Reunión de la Sociedad Andaluza de Patología Digestiva. Revista Andaluza de Patología Digestiva 1999; 22 (número extraordinario): 121-2(s). [ Links ]

79. Baixauli A, Boluda J, Raussell N, Tamarit JJ, Pavón MA, Calvo J, et al. Un nuevo caso de enfermedad de Whipple. Revista de la Sociedad Valenciana de Patología Digestiva, 4. 1999; 18: 165-9. [ Links ]

80. Rego MI, Suñol M, Malet A. Conferencia clínico-patológica MIR. Med Clin 2000; 114: 784-9. [ Links ]

81. Herrero M, Jiménez-Mejías ME, Alberca R, Luque-Baronac R, Pichardo C, Bernabeu M. Síndrome febril de larga evolución y demencia. Enf Infec Microbiol Clin 2000; 18: 187-8. [ Links ]

82. Reyes Martínez C, Reina Campos FR, García Fernández FJ, Jiménez Macías FM, Giráldez Gallego JA, Lucero Pizones C, et al. Enfermedad de Whipple: análisis de los casos diagnosticados en nuestro hospital en los últimos 20 años. XXXI Reunión de la Sociedad Andaluza de la Patología Digestiva. Revista Andaluza de Patología Digestiva 2001; 24 (número extraordinario): 28(s). [ Links ]

83. Hernández Echevarria L, Tejada J, Fernández F, Vadillo ML, Cabezas B, Ares A, et al. Enfermedad de Whipple. En busca del tratamiento ideal. LIII Reunión de la Sociedad Española de Neurología. Póster. Neurología 10. 2001; 16: 501-619. [ Links ]

84. Tarroch X, Vives P, More J, Salas A. XXVI Reunión Nacional del Grupo Español de Dermopatología. Bilbao. Actas Dermo-sifiliográficas. 2001; 92(Supl. 2): 187-212. [ Links ]

85. Maizel H, Ruffin JM, Dobbins WO. Whipple's disease: a review of 19 patients from one hospital and a review of the literature since 1950. Medicine (Baltimore) 1970; 49: 175-205. [ Links ]

86. Durand DV, Lecomte C, Cathebras P, Rousset H, Godeau P, and the SNFMI Research Group on Whipple's disease: Whipple's disease. Clinical review of 52 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 1977; 76: 170-84. [ Links ]

87. Alkan S, Beals TH, Schintzer B. Primary diagnosis of Whipple disease manifesting as lymphadenopathy. Am J Clin Pathol 2001; 116: 898-904. [ Links ]

88. Alba D, Molina F, Vázquez JJ. Manifestaciones neurológicas de la enfermedad de Whipple. An Med Inter (Madrid) 1995; 12: 508-12. [ Links ]

89. Enzinger FM, Helwing EB. Whipple's disease. A review of the literature and report of fifteen patients. Virchows Arch Pathol Anat 1963; 336: 238-69. [ Links ]

90. Winberg CD, Rose ME, Rappaport H. Whipple's disease of the lung. Am J Med 1978; 65: 873-80. [ Links ]

91. Fleming JL, Wiesner RH, Shorter RG. Whipple's disease: clinical, biochemical and histopathologic features and assessment of treatment in 29 patients. Mayo Clin Proc 1988; 68: 539-51. [ Links ]

92. De Takats PG, De Takats DI, Iqbal TH, Watson RD, Sheppard MN, Cooper BT. Symptomatic cardiomyophaty as a presentation in Whipple's disease. Postgrad Med J 1995; 71: 236-9. [ Links ]

93. Silvestry FE, Kim B, Pollack BJ, Haimowitz JE, Murray RK, Furth EE, et al. Cardiac Whipple disease: identification of Whipple bacillus by electron microscopy in the myocardium of a patient before death. Ann Intern Med 1997; 126: 214-6. [ Links ]

94. Cohen L, Berthet K, Cauga C, Thivarts S, Pierrot-Deseilligny C. Polymerase chain reaction of cerebrospinal fluid to diagnose Whipple's disease (letter). Lancet 1996; 347:329. [ Links ]

95. O'Duffy J.D, Griffing WL, Li CY, Abdelmalek MF, Persing PH. Whipple's arthritis. Direct detection of Tropheryma whipplei in synovial fluid and tissue. Arthritis Rheum 1999; 42: 812-7. [ Links ]

96. Muller C, Stain C, Burghuber O. Tropheryma whipplei in peritoneal blood mononuclear cells and cells of pleural et fussion. Lancet 1993; 341: 701. [ Links ]

97. Rickman LS, Freeman WR, Green WR, Feldman ST, Sullivan J, Russack V, et al. Brief report: uveitis caused by Tropheryma whipplei (Whipple's bacillus). N Engl J Med 1995; 332: 363. [ Links ]

98. Gross M, Jung C, Zoller WG. Detection of Tropheryma whipplei DNA (Whipple's disease) in faeces. Ital J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1999; 31: 70-2. [ Links ]

99. Gilbert DN, Moellering RC, Sande MA. Guía de terapéutica antimicrobiana Sanford. Versión Española de la Edición, 2001. [ Links ]

100. Marth T, Neurath M, Cuccherini BA, Strober W. Defects of monocyte interleukin-12 production and humoral immunity in Whipple's disease. Gastroenterology 1997; 113: 442-8. [ Links ]

101. Schneider T, Stallmach A, von Herbay A, Marth T, Strober W, Seitz M. Treatment of refractory Whipple disease with Interferon-gamma. Annal Intern Med 1998; 129: 875-7. [ Links ]

102. Ojeda E, Cosme A, Lapaza J, Torrado J, Arruabarrena I, Alzate L. Whipple's disease in Spain: clinical review of 91 cases (abstract). Eur J Intern Med 2003; 14(Supl. 1): 46. [ Links ]

103. Keinath RD, Merrell DE, Vliestra E, Dobbins WO. Antibiotics treatment and relapse in Whipple's disease. Long-term follow-up of 88 patients. Gastroenterology 1985; 88: 1867-73. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Ángel Cosme Jiménez.

Servicio de Aparato Digestivo.

Hospital Donostia. Paseo Doctor Beguiristain,

s/n. 20014 San Sebastián, Guipúzcoa. Spain.

e-mail: acosme@chdo.osakidetza.net

Received: 06-05-09.

Accepted: 14-05-09.

texto en

texto en