Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.105 no.2 Madrid feb. 2013

https://dx.doi.org/10.4321/S1130-01082013000200005

Factors related to length of hospital admission in mild interstitial acute pancreatitis

Factores relacionados con la duración de la estancia hospitalaria en pancreatitis aguda intersticial

María Francisco, Fátima Valentín, Joaquín Cubiella and Javier Fernández-Seara

Department of Gastroenterology. Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Ourense. Ourense, Spain

This article has been presented to the following congresses: Semana de Enfermedades Digestivas. Seville (Spain), 11-14 June 2011, 19th United European Gastroenterology Week (Spain). Stockholm, 22-26 October 2011 and XV Reunión de la Asociación Española de Gastroenterología. Madrid 21-23 marzo de 2012.

ABSTRACT

Objectives: to describe the clinical practice and the factors associated with length of hospital stay in mild acute pancreatitis.

Methods: we present a retrospective observational study that includes a series of patients admitted to our hospital between January 2007 and December 2009 due to mild acute pancreatitis. Baseline data, treatments and examinations were collected. Variables associated with the length of hospital were determined using a Cox proportional hazards model.

Results: 232 patients were included (median age 74.3 years, bedside index for severity in acute pancreatitis score 1, comorbidity Charlson score 1, 52.6 % male). 75.9 % were admitted to the gastroenterology department. Oral diet was reintroduced at 3 (0-11) days and 28 patients (12 %) were intolerant to oral re-feeding. Abdominal ultrasound, a magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, endoscopic ultrasound, a computed tomographic scan, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography were performed in 92.2, 34.5, 9.5, 28.4 and 14.7 % of admissions, respectively. The length of hospital stay was 8 (1-31) days. The variables independently associated with length of admission were: Charlson index ≥ 2 (hazard ratio-HR-1.4, 95 % confidence interval-CI- 1.06-1.84; p: 0.017), admission in gastroenterology department (HR 0.67, 95 % CI 0.49 to 0.93; p: 0.016), fasting period ≥ 3 days (HR 1.37, 95 % CI 1.05-1.78; p: 0.02), intolerance to oral re-feeding (HR 1.8, 95 % CI 1.17-2.77; p: 0.007), performance of computed tomographic scan (HR 2.05, 95 % CI 1.49-2.82; p < 0.001), magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (HR 1.87, 95 % CI 1.42-2.49; p < 0.001) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (HR 2.23, 95 % CI 1.51-3.3; p < 0.001).

Conclusions: the variables associated with length of hospital stay were comorbidity, department in charge, fasting period, food intolerance and complementary explorations.

Key words: Pancreatitis. Physician's practice patterns. Patient admission.

Introduction

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is an acute inflammatory process of the pancreas with variable systemic and peripancreatic tissues involvement (1,2). AP is classified as mild if is associated with minimal or no organ dysfunction and has a good evolution, or severe if it develops organ failure, local complications (necrosis, abscess or pseudocyst) or both (1,2). Fortunately, 80 % of AP have a mild course (3). Clinical practice guidelines and expert recommendations published in recent years have attempted to determine the optimal characteristics of care, treatment and examinations to perform in AP (2-6).

AP is a frequent reason for hospital admission. Number of admissions varies between 3 and 5 cases per 10,000 inhabitants-year (7) with 226,000 patients admitted to hospital in U.S. annually. The global cost is 5,400 million $, the cost per admission is 24,000 $, and the cost per admission-day is 1,670 $ (8). Several economic studies have evaluated factors associated with hospitalization costs. The admission cost have been related to length of hospital stay, AP severity, age, comorbidity, requirement of surgical treatments, antibiotics, enteral nutrition and intensive care unit admission (8,9).

Although mild AP is the most frequent evolution of AP and mortality risk is minimal (3,4,6), there is little information on clinical practice, length of hospitalization and which factors are associated. This information is relevant to determine cost-effectiveness in clinical practice in mild cases, since length of hospital stay is one of the main factors related to hospitalization costs. For this reason, we conducted a study to determine clinical practice in our area as well as the factors associated with length of hospital stay in mild AP.

Patients and methods

Study design

We conducted an observational, descriptive, retrospective, cross-sectional study based on the review of the clinical documentation and clinical history databases at our hospital. We reviewed the clinical records of patients with a diagnosis of AP at discharge between January 2008 and December 2009. Our study was initially designed to analyze the frequency of intolerance to re-feeding in mild AP, the method of treating such intolerance and related factors in a consecutive series of patients (10). Therefore, this study is a secondary analysis of the included data.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Each patient's first episode of mild interstitial AP in the study period was included. AP was defined as any episode that met two or more of the following criteria: Epigastric abdominal pain suggestive of AP, elevation of serum amylase to a level greater than three times the upper limit of normal and compatible diagnostic imaging technique. The following were excluded from the study: Any patient who presented with multiorganic systemic failure in the first 48 hours or developed pancreatic necrosis during follow-up (1,3,6), inhospital AP, recurrent AP, death during admission, age under 18 years, any patient transferred from another hospital and any patient whose reason for admission did not correspond to AP.

Dependent variable

The main dependent variable was the length of hospital admission defined as number of hospitalization days.

Study variables

Demographic variables (age and sex) and comorbidity using the Charlson comorbidity index (11) were recorded for each patient. Specific co-morbidities were not evaluated. The following data were collected on admission: length of symptoms before admission (based on clinical records); clinical variables (blood pressure, heart beat rate and temperature); analytical data (serum amylase, glucose, aspartate aminotransferase, creatinine, urea and total serum calcium, hematocrit and leukocyte counts); and presence of pleural effusion. The bedside index for severity in acute pancreatitis (BISAP) was determined on admission (12).

We registered the department in charge of the patient and the treatment administered during the first 48 hours: volume of intravenous hydration administered, analgesia and antiemetics. The amount of opiate derivatives administered was quantified using scales of equivalence among the respective opiates in milligrams of morphine chloride (mg pentazocine x 0.100, meperidine x 0.134). Other analgesics, such as paracetamol, metamizole and scopolamine butylbromide, were also registered. We also collected fasting period, oral re-feeding mode and intolerance to it. The attending physician in the emergency department determined the department in charge. On the other hand, clinical decision about re-feeding was based on improvement in or disappearance of AP-related symptoms, i.e., absence of pain, presence of peristalsis, and disappearance of vomiting. Intolerance to oral diet was defined as the appearance of pain, nausea or vomiting associated with reintroduction of diet, as previously described (10).

Finally, we also recorded data on any complementary examinations conducted, such as abdominal ultrasound, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS), computed tomography (CT) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), including the most relevant findings, e.g., lithiasis, choledocholithiasis, presence of peripancreatic collections and CT severity index (13). Complementary examinations were performed according to clinical judgment, i.e ERCP was performed when a common bile duct obstruction was suspected. AP etiology was determined on the basis of clinical assessment.

Statistical analysis

The data were entered into a database. Initially, we made a descriptive analysis of the study variables with qualitative variables being expressed as absolute numbers and percentages, and quantitative variables as median and its range. A univariate analysis was performed (t-test in the cuantitative variables and Chi-square test in the qualitative variables) to detect if there were differences between patients according to the department in charge. To determine variables related with length of admission, all quantitative variables were transformed into qualitative variables using mean as cut-off value. A survival analysis with Kaplan-Meier method was performed. Variables were compared with Log-Rank test to determine differences in length of hospital stay. Finally, all statistically significant variables were included in a Cox multivariate proportional risks model (stepwise forward) after excluding collinearity among variables included in the final model. The association with length of hospitalization was expressed as hazard ratios (HR) with 95 % confidence intervals (CI). In all cases, differences with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical calculations were performed using the SPSS statistical software, version 15.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago IL).

Ethical aspects

The study was approved by the Galician Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Code 2010/142) under decision dated 27-04-2010. Patients' clinical histories were accessed for study purposes in accordance with the research protocols available in our hospital's clinical documentation department.

Finally, we used the STROBE checklist for cross sectional studies to design the study and to write this original article (14).

Results

Descriptive analysis

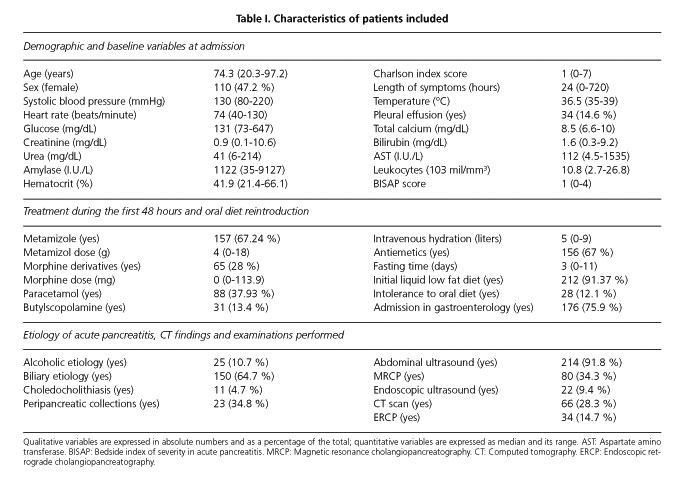

During the inclusion period, 252 patients were admitted in our hospital on 303 occasions and were discharged with the diagnoses of AP. Seventy one episodes in 51 patients were excluded for the following reasons: AP relapse (51), severe AP (11), in-hospital AP (2), death (16) and other diagnosis (2). Finally, 232 patients were included in the study. The Charlson comorbidity index score was: 0 points-77 patients, 1 point-75, 2 points-42, 3 points-22, 4 points-10 and ≥ 5 points-6. BISAP score was 0 points-54 patients, 1 points-89, 2 points-66, 3 points-20 and 4 points-3. Description of patients' hemodynamic constants and analytical determinations on admission and length of symptoms before admission are described in table I.

One hundred and seventy six (75.9 %) patients were admitted to the gastroenterology department; the remaining patients were admitted to the internal medicine department (40) and surgery department (16). With respect to the treatment during the first 48 hours, the median amount of intravenous hydration administered was 5,000 (0-9,000) milliliters. In 156 (67 %) patients, antiemetic treatment was administered (119 on demand, 37 scheduled). With respect to analgesics, 157 (67.24 %) patients received metamizole, 65 (28 %) were given some morphine derivative, 88 (37.93 %) required paracetamol, and 31 received butylscopolamine (13.4 %). Diet was reintroduced at 3 (0-11) days (Fig. 1). Feeding was initiated with a low-fat liquid diet in most patients (91 %) and with a solid diet in 21 (9 %). At 1 (0-14) day, 28 (12 %) patients developed intolerance to oral diet. The treatments given in the first two days, as well as the dose of metamizole and opioids administered are shown in table I.

AP was catalogued as lithiasic in 150 (64.7 %), alcoholic in 25 (10.7 %), related to other causes in 13 (5.6 %) and idiopathic in 44 (18.9 %) cases. Choledocholithiasis was detected in 11 patients and was treated by endoscopic extraction. The tests performed were abdominal ultrasound in 214 (91.8 %), MRCP in 80 (34.3 %), CT scan in 66 (28.3 %), EUS in 22 (9.4 %) and ERCP in 34 (14.7 %) patients. CT severity index was A-18, B-4, C-20, D-8 and E-15, with peripancreatic collections detected in 34.84% of patients evaluated with CT. Data on etiology and examinations performed are listed in table I.

Regarding to the department in charge, no differences in the variables at admission or AP etiology were found in the univariate analysis. Instead, we found differences between gastroenterology and other departments in the volume of fluid administered in the first 48 hours (5.4 ± 1.1 liters, 4.7 ± 1.3 litros, p < 0.001), in the frequency of progressive re-feeding (93.8 %, 82.1 %, p = 0.01), performance of abdominal ultrasound (94.3 %, 85.7 %, p = 0.04), EUS (12.5%, 0 %, p = 0.03) or CT (24.4 %, 41.1 %, p: 0.001).

Length of hospital admission and factors associated

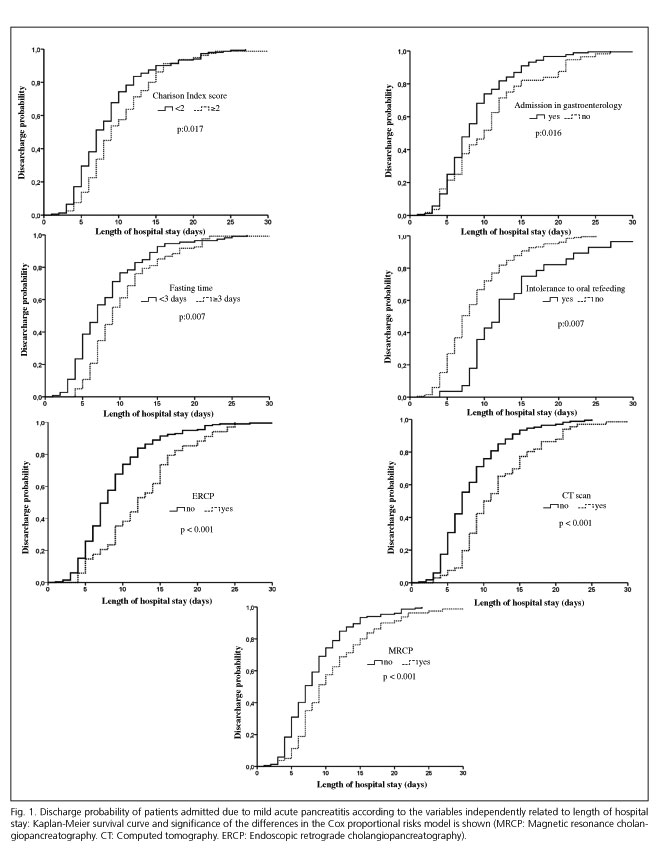

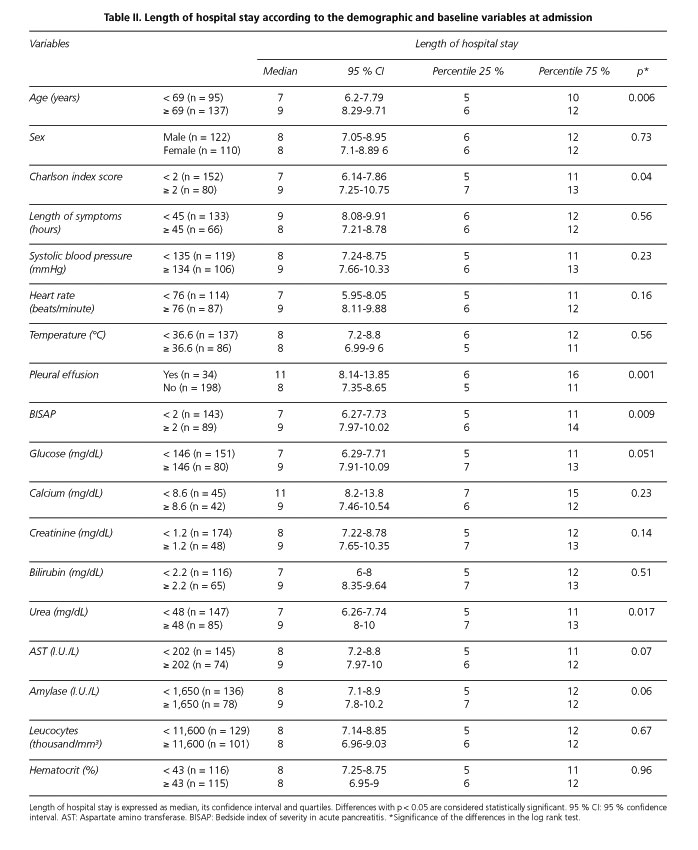

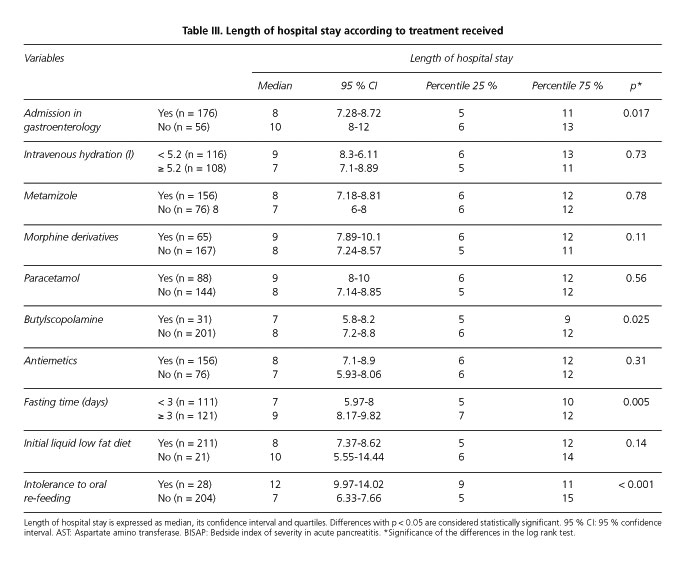

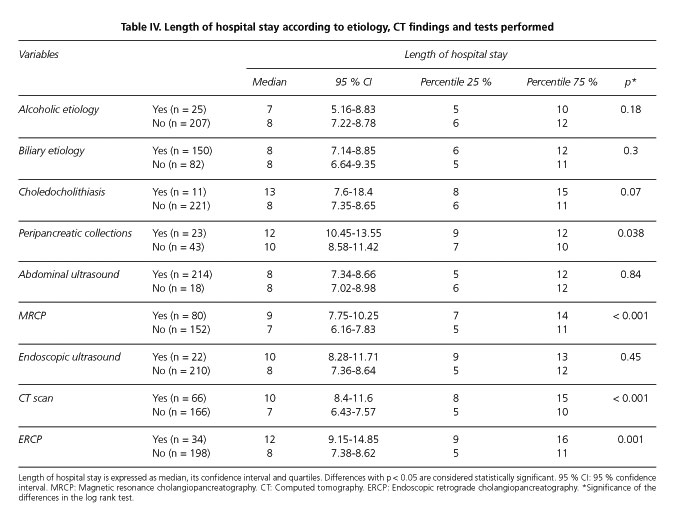

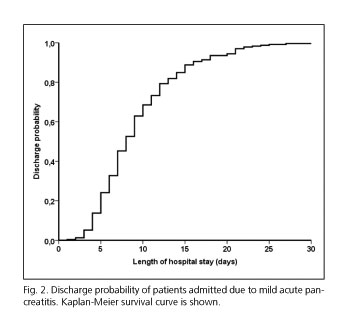

Median time of hospitalization was 8 (1-31) days (Fig. 1). In Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, variables associated with a prolonged length of hospital stay were age ≥ 69 years (p: 0.006), Charlson comorbidity score ≥ 2 (p: 0.04), pleural effusion (p: 0.001), BISAP scale score ≥ 2 (p: 0.009), blood urea ≥ 48 mg/dl (p: 0.017), fasting time ≥ 3 days (p: 0.005), intolerance to oral re-feeding (p < 0.001) and conducting additional explorations: CT scan (p < 0.001), MRCP (p < 0.001) and ERCP (p: 0.001). On the other hand, admission to gastroenterology department (p: 0.017) and butylscopolamine treatment (p: 0.025) were related to a decrease in hospital length of admission as it can be observed in tables II, III y IV

After entering these variables in a Cox proportional hazards model, the factors independently associated with the length of hospital admission were Charlson index score ≥ 2 (HR 1.4, 95 % CI 1.06-1.84), admission to gastroenterology department (HR 0.67, 95 % CI 0.49 to 0.93), fasting time ≥ 3 days (HR 1.37, 95 % CI 1.05-1.78), intolerance to oral re-feeding (HR 1.8, 95 % CI 1.17-2.77), conducting CT scan (HR 2.05, 95 % CI 1.49-2.82), MRCP (HR 1.87, 95 % CI 1.42-2.49) and ERCP (HR 2.23, 95 % CI 1.51-3.3). No collinearity was found among the variables included in the final model. Figure 2 shows the survival curves according to the variables independently associated with the length of hospital admission.

Discussion

Our study has determined that a prolonged period of hospital admission is associated with the department in charge of the patient, severe comorbidity, fasting time, intolerance to oral re-feeding and the additional examinations required. We have also described what treatments the patients received in the first two days as well as the tests performed during hospitalization.

Clinical practice guidelines and expert consensus available aim to make recommendations on diagnosis, management and treatment based on available evidence. In AP, the level of evidence is low with a small number of randomized trials (3). The recommendations have focused especially on the diagnosis, prevention and treatment of complications associated with AP (2-6). So, information on the optimal treatment and management in mild episodes of AP (type of analgesia, mode and timing of oral re-feeding, hydration volume, complementary tests and criteria to discharge) is limited. As an example, there is a great variability in length of hospital admission in terms of geographical area and type of hospital (7,15). So, while AP mean hospital length of stay is between 5.3 and 6.1 days in U.S. (16), mild AP hospital stay is between 17.5 and 18.1 days in Japan (15). Our study has described clinical practice in mild AP in our area. This information is necessary to develop strategies to improve cost-effectiveness management in a disease with a nearly universal recovery without sequelae. Thus, we need more evidence on the optimal treatment (timing of oral re-feeding, intravenous hydration, analgesia) and management (complementary examinations required, early discharge) of mild AP.

Our study has several strengths. It is based on a review of medical records of AP consecutive admissions at our institution over a period of two years. We were able to certify whether the diagnosis contained in the administrative databases corresponded to the clinical diagnostic criteria (1). Most of the studies that have analyzed AP length of hospital admission are based in the International Classification of Diseases codes as a method to identify AP, too. However, these studies did not have access to clinical data (7-9). For this reason, we were able to analyze not only the demographic variables available in administrative databases, but also the effect of prognostic scales, treatments applied and tests performed on length of hospital stay. As previously mentioned, we restricted our analysis to mild AP as long as most of the episodes are self-limited and length of hospitalization is independently associated with the severity of the episode, admission in intensive care and surgical treatment (15).

Our study has identified those factors are associated with a prolonged hospital stay. Previous studies have determined that severe comorbidity is associated with increasing mortality in AP (15,16), but not with an increased length of hospitalization (15). Moreover, we have determined that admission to gastroenterology department led to a reduction of 2 days in the median time of admission. Although no data are available on the effect of the department in charge of the patient during admission, this difference may be related to the development of specific protocols based on the implementation of clinical guidelines and on continuing education. In fact, it is known that, length of hospital stay is shorter (7,15,16), and mortality risk as well as the likelihood of requiring invasive procedures (ERCP, surgical treatment) is lower in hospitals with higher volume of AP admissions (7,16). Nevertheless, no information is available on the AP volume and the length of hospital stay in mild AP. It is noteworthy that Singla et al. (16), defined an AP high volume admission hospital as a hospital with more than 118 admissions-year due to AP. In our center, we identified 303 AP admissions in a two year period.

Finally, we have confirmed the relationship between intolerance to re-feeding, fasting time and a longer hospital stay already documented in previous studies (17-19). The timing and mode of oral re-feeding in mild pancreatitis is not clearly defined. In retrospective series, intolerance to the oral re-feeding is a variable phenomenon: 12-24.6%. In these studies, the appearance of intolerance was associated with an increased hospital stay, but not with a worse outcome (10,17-19). However, recently published randomized studies have evaluated different modes of re-feeding in mild AP. They compared re-feeding with liquid, soft or complete diets when symptoms disappeared. These studies found no differences in terms of intolerance to re-feeding (20-22). On the other hand, a small randomized study comparing immediate re-feeding in the moment of admission against oral re-feeding when symptoms disappear, detected no differences in terms of intolerance or complications (23). These studies have only detected a shorter length of hospital admission in patients treated with full or immediate oral re-feeding (21-23).

We have also determined an association between the need for performing complementary tests with a longer length of hospital stay. This relationship has two implications. First, it is necessary to develop clinical pathways to define what examinations are required and when to perform them. On the other hand, this relationship may be related to a persistent clinical course of mild AP. Recently a new subgroup of AP, named moderately severe AP, has been described and validated. This subgroup has been characterized by the presence of local complications without systemic complications and is associated with a longer hospitalization and a greater need for interventions than mild AP (24).

The main limitation of our study is that it is a single-center study. We cannot rule out that some of the factors associated with length of hospitalization may be related to specific clinical practices performed in our center. However, it is noteworthy that our length of admission falls within the ranges previously described (15,16). Furthermore, clinical practice in mild AP meets the criteria set out in the experts recommendations available in our area (2-6). Besides, our study is based on the retrospective analysis of clinical records. In this sense, we could not consistently evaluate several variables at admission that may be related with severity of AP as well as length of hospital stay: APACHE score, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, Balthazar score, C-reactive protein. In fact, these findings should be validated in the context of a prospective multicenter study to evaluate also the economic aspects associated with the treatment of mild AP.

Another limitation of our study lies on the statistical analysis. Our aim was to describe which variables were related to the length of hospital stay. We did not try to design a predictive model. For this reason, we decided to transform quantitative into qualitative variables to facilitate the interpretation of the results. Although we could have determined the optimal cut-off point on the basis of receiver operating characteristic curves and the Youden index, instead of mean value, this approach would generate a greater difficulty in the results interpretation.

In conclusion, our study has described the clinical practice in mild AP, length of hospital admission and the factors associated with it. These data should be used to establish cost-effective guidelines in the diagnosis and treatment of mild AP.

Acknowledgments

To Fiona Chapman and Cristina Rosón Calvo for their help in the correction of the manuscript.

References

1. Bradley E. A clinically based classification system for acute pancreatitis. Summary of the international Symposium on Acute Pancreatitis. Arch Surg 1993;128:586-90. [ Links ]

2. Working Party of the British Society of Gastroenterology; Association of Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland; Pancreatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland; Association of Upper GI Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland. UK guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Gut 2005;54:1-9. [ Links ]

3. Forsmark CE, Baillie J. AGA Institute technical review on acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2007;132:2022-44. [ Links ]

4. Banks PA, Freeman ML. Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:2379-400. [ Links ]

5. Takada T, Kawarada Y, Hirata K, Mayumi T, Yoshida M, Sekimoto M, et al. JPN Guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis: cutting-edge information. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2006;13:2-6. [ Links ]

6. Navarro S, Amador J, Arguello K, Ayuso C, Boadas J, de las Heras G, et al. Recommendations of the Spanish Biliopancreatic Club for the treatment of acute pancreatitis. Consensus development conference. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;31:366-87. [ Links ]

7. Singla A, Simons J, Li Y, Csikesz NG, Ng SC, Tseng JF, et al. Admission volume determines outcome for patients with acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2009;137:1995-2001. [ Links ]

8. Fagenholz PJ, Fernández-del Castillo C, Harris NS, Pelletier AJ, Camargo CA. Direct medical costs of acute pancreatitis hospitalizations in the United States. Pancreas 2007;35:302-7. [ Links ]

9. Murata A, Matsuda S, Mayumi T, Okamoto K, Kuwabara K, Ichimiya Y, et al. Multivariate analysis of factors influencing medical costs of acute pancreatitis hospitalizations based on a national administrative database. Dig Liver Dis 2012;44:143-8. [ Links ]

10. Francisco M, Valentín F, Cubiella J, Alves MT, García MJ, Fernández T, et al. Factors associated with intolerance after re-feeding in mild acute pancreatitis. Pancreas 2012;41:1325-30. [ Links ]

11. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373-83. [ Links ]

12. Wu BU, Johannes RS, Sun X, Tabak Y, Conwell DL, Banks PA. The early prediction of mortality in acute pancreatitis: a large population-based study. Gut 2008;57:1698-703. [ Links ]

13. Balthazar E, Robinson D, Megibow A, Ranson J. Acute pancreatitis: value of CT in establishing prognosis. Radiology 1990;174:331-6. [ Links ]

14. Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61: 344-9. [ Links ]

15. Murata A, Matsuda S, Mayumi T, Yokoe M, Kuwabara K, Ichimiya Y, et al. Effect of hospital volume on clinical outcome in patients with acute pancreatitis, based on a national administrative database. Pancreas 2011;40:1018-23. [ Links ]

16. Singla A, Csikesz NG, Simons JP, Li YF, Ng SC, Tseng JF, et al. National hospital volume in acute pancreatitis: analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample 1998-2006. HPB (Oxford) 2009;11:391-7. [ Links ]

17. Chebli JMF, Gaburri PD, De Souza AFM, Junior EVM, Gaburri AK, Felga GEG, et al. Oral re-feeding in patients with mild acute pancreatitis: prevalence and risk factors of relapsing abdominal pain. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005;20:1385-9. [ Links ]

18. Lévy P, Heresbach D, Pariente E, Boruchowicz A, Delcenserie R, Millat B, et al. Frequency and risk factors of recurrent pain during re-feeding in patients with acute pancreatitis: a multivariate multicentre prospective study of 116 patients. Gut 1997;40:262-6. [ Links ]

19. Petrov MS, Van Santvoort HC, Besselink MGH, Cirkel GA, Brink MA, Gooszen HG. Oral re-feeding after onset of acute pancreatitis: a review of literature. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:2079-84. [ Links ]

20. Jacobson BC, Vander Vliet MB, Hughes MD, Maurer R, McManus K, Banks PA. A prospective, randomized trial of clear liquids vs. low-fat solid diet as the initial meal in mild acute pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;5:946-51. [ Links ]

21. Sathiaraj E, Murthy S, Mansard MJ, Rao G V, Mahukar S, Reddy DN. Clinical trial: Oral feeding with a soft diet compared with clear liquid diet as initial meal in mild acute pancreatitis. Alim Phar Ther 2008;28:777-81. [ Links ]

22. Moraes JM, Felga GE, Chebli LA, Franco MB, Gomes CA, Gaburri PD, et al. A full solid diet as the initial meal in mild acute pancreatitis - is safe and result in a shorter length of hospitalization. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:517-22. [ Links ]

23. Eckerwall GE, Tingstedt BB, Bergenzaun PE, Andersson RG. Immediate oral feeding in patients with mild acute pancreatitis is safe and may accelerate recovery -A randomized clinical study. Clin Nut 2007;26:758-63. [ Links ]

24. Talukdar R, Clemens M, Vege SS. Moderately severe acute pancreatitis. Pancreas 2012;41:306-9. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Joaquín Cubiella

Department of Gastroenterology

Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Ourense

C/ Ramón Puga, 52-54

32005 Ourense, Spain

e-mail:

joaquin.cubiella.fernandez@sergas.es

Received: 19-11-2012

Accepted: 20-02-2013