Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.106 no.2 Madrid feb. 2014

https://dx.doi.org/10.4321/S1130-01082014000200002

An economic analysis of inadequate prescription of antiulcer medications for in-hospital patients at a third level institution in Colombia

Análisis económico de la prescripción inadecuada de antiulcerosos en pacientes hospitalizados en institución de tercer nivel de Colombia

Jorge Enrique Machado-Alba1, Juan Daniel Castrillón-Spitia2, Manuel José Londoño-Builes2, Alejandra Fernández-Cardona2, Carlos Felipe Campo-Betancourth2, Sergio Andrés Ochoa-Orozco2, Luis Felipe Echeverri-Cataño2, Joaquín Octavio Ruiz-Villa2 and Andrés Gaviria-Mendoza2

1Pharmacology. Grupo de Investigación en Farmacoepidemiología y Farmacovigilancia. Universidad Tecnológica de Pereira-Audifarma S.A

2Health Sciences Faculty. Grupo de Investigación en Farmacoepidemiología y Farmacovigilancia. Universidad Tecnológica de Pereira-Audifarma S.A. Pereira, Colombia

Universidad Tecnológica de Pereira and Audifarma S.A for co-financing this work.

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The prescription and costs of antiulcer medications for in-hospital use have increased during recent years with reported inadequate use and underused.

Aim: To determine the patterns of prescription-indication and also perform an economic analysis of the overcost caused by the non-justified use of antiulcer medications in a third level hospital in Colombia.

Materials and methods: Cross-sectional study of prescription-indication of antiulcer medications for patients hospitalized in "Hospital Universitario San Jorge" of Pereira during July of 2012. Adequate or inadequate prescription of the first antiulcer medication prescribed was determined as well as for others prescribed during the hospital stay, supported by clinical practice guidelines from the Zaragoza I sector workgroup, clinical guidelines from the Australian Health Department, and finally the American College of Gastroenterology Criteria for stress ulcer prophylaxis. Daily defined dose per bed/day was used, as well as the cost for 100 beds/day and the cost of each bed/drug. A multivariate analysis was carried out using SPSS 21.0.

Results: 778 patients were analyzed, 435 men (55.9%) and 343 women, mean age 56.6 ± 20.1 years. The number of patients without justification for the prescription of the first antiulcer medication was 377 (48.5%), and during the whole in-hospital time it was 336 (43.2%). Ranitidine was the most used medication, in 438 patients (56.3%). The cost/month for poorly justified antiulcer medications was € 3,335.6. The annual estimated cost for inadequate prescriptions of antiulcer medications was € 16,770.0 per 100 beds.

Conclusion: A lower inadequate prescription rate of antiulcer medications was identified compared with other studies; however it was still high and is troubling because of the major costs that these inadequate prescriptions generates for the institution.

Key words: Antiulcer agents. Inappropriate prescribing. Economics pharmaceutical. Costs and cost analysis. Proton pump inhibitors. Histamine H2 antagonist. Hospitalization.

RESUMEN

Introducción: la prescripción y coste de antiulcerosos a nivel hospitalario se incrementaron en años recientes, reportándose usos inadecuados.

Objetivo: determinar los patrones de prescripción-indicación y el análisis económico del sobrecoste por uso injustificado de antiulcerosos en un hospital de tercer nivel de atención en Colombia.

Materiales y métodos: estudio de corte transversal, de prescripción-indicación de antiulcerosos en pacientes internados en el Hospital Universitario San Jorge de Pereira en julio 2012. Se determinaron: indicación adecuada o inadecuada del primer antiulceroso prescrito y del prescrito durante la hospitalización, apoyados en guías de práctica clínica del Grupo de Trabajo Sector Zaragoza I, del Departamento Gubernamental Australiano de la Salud y los criterios del Colegio Americano de Gastroenterología para profilaxis de úlceras de estrés. Se definió la dosis diaria definida por cama/día, se obtuvo el coste por 100 camas/día y costes de cada medicamento. Se hizo análisis multivariado mediante SPSS 21.0.

Resultados: se analizaron 778 pacientes, 435 hombres (55,9%) y 343 mujeres, edad promedio 56,6 ± 20,1 años. No tenían justificación para la prescripción del primer antiulceroso 377 pacientes (48,5%), ni durante toda la hospitalización 336 pacientes (43,2%). Ranitidina fue el más usado en 438 pacientes (56,3%). El coste/mes por antiulcerosos no indicados fue 3.335,62 €. El coste anual estimado por inadecuada prescripción de antiulcerosos fue 16.770,0 € por 100 camas.

Conclusión: se presentó una menor prescripción inadecuada de antiulcerosos en comparación con otros estudios, sin embargo sigue siendo alta y preocupante por los importantes costes en que incurre la institución para financiar medicamentos que no requieren los pacientes.

Palabras clave: Antiulcerosos. Prescripción inadecuada. Economía farmacéutica. Costos y análisis de costo. Inhibidores de la bomba de protones. Antagonistas de los receptores histamínicos H2. Hospitalización.

Introduction

The prescription of antiulcer medications and their costs both in the in-hospital and outpatient environment have increased during recent years. In England, the costs for antiulcer medications reached € 100,000,000 in 2006, with omeprazole as the most sold prescription. In the United States, esomeprazole sales alone surpassed € 4.5 billion in 2009, whereas the whole pharmacologic group constituted by the proton pump inhibitors was the third most sold group in the country (1-3).

In the inpatient environment, antiulcer medications use has been justified for stress ulcer prophylaxis and treatment, but few of the patients truly require the prescription (4-6). Additionally, they have been used for different indications from those recommended, as polymedication, with the exception of gastrolesive drugs, which present clearer indications for their prescription, including criteria such as age and risk factors for upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage, and are not simply used as mucosa protectors (5-7).

Furthermore, the increased risk of adverse reactions in patients with multiple medications must be considered when they also start receiving antiulcer medication; indeed PPI have been associated with atrophic gastritis, interstitial nephritis, osteoporosis, gynecomastia, arrhythmias, and pneumonia, among others, and H2 antagonists (AntiH2) have been associated with diarrhea, dizziness, headache, acid hyper secretion rebound effect, and arrhythmias, as well as hematologic and hepatic alterations. These drugs may also mask certain illnesses, and multiple studies in different countries all around the world have shown excess costs incurred by health systems as a consequence of inadequate use of antiulcer medications that it has reported up to 80% of the cases (4,11-15).

There have been no studies published in Colombia about the prescription and indication of antiulcer medications in the inpatient environment, and on the continent these kinds of studies are few in number. So it was decided to determine and evaluate the patterns of prescription-indication of these medications in a tertiary level hospital in a Colombian city and make an economic analysis of the excess cost that their unjustified use generates, in order to create educational measures for their management in patients and healthcare givers.

Patients and methods

A cross-sectional study of prescription indication in patients hospitalized in the Hospital Universitario San Jorge (HUSJ), in Pereira, to whom at least one antiulcer medication was prescribed between July 1st and 31st, 2012. The selected month was chosen randomly, avoiding January and December because those months show atypical behavior in the number of hospitalizations; the information was collected from the whole population, older than 18years old, of any gender, who received attention in the services of urgent care, observation, internal medicine, surgery, the intermediate care unit, intensive care unit, gynecology and obstetrics. The dispensation of the drugs was reported by the pharmacy of the hospital and the clinical records of the patients, with prior authorization by the hospital, were reviewed. A database of drug formulation was validated and reviewed by the authors to minimize, selection and information bias.

The main variables were the determination of adequate or inadequate first antiulcer treatment prescribed at the time of hospitalization and the same determination during the course of hospitalization. Switches or additions of antiulcer drugs in the same patient (route of administration or an additional antiulcer medication) were considered, and each was analyzed as a new antiulcer therapy.

Inappropriate prescription of antiulcer therapy was defined as outlined in Clinical Practice Guidelines for the use of PPI from the Zaragoza I workgroup and Clinical Practice Guidelines from the Australian Government Health Department (16,17). Their use in non-ulcer dyspepsia, peptic disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease, Helicobacter pylori eradication, Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome, Barrett's esophagus, histological diagnostic of gastritis, and when the patient use a gastrolesive drugs, were considered adequate indications for antiulcer medication therapy. Indication of stress ulcer prophylaxis according to the criteria of the American College of Gastroenterology (18) was added to the accepted indications. Other indications with weak evidence for use, such as esophageal varices, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with biopsy, personal history of gastritis without diagnostic confirmation and anemia without determining etiology were also accepted (16,17).

The study included socio-demographic variables (age, gender, affiliation with the Health System, city of provenance, origin of remission); clinical variables (main diagnosis, secondary diagnoses, length of hospital stay, confirmatory analytical test for peptic ulcer, upper gastrointestinal bleeding and acid-peptic disease) (16-18); and pharmacological variables (prescribed antiulcer medications, route of administration, duration, dosage, other medications, hospital service where antiulcer therapy started, higher complexity hospitalization service reached like critic care unit) including polypharmacy -minor (2 or 3 concomitant drugs), moderate (4-5) and major (≥ 6) (5).

For the economic analysis the defined daily dose per bed-day (DHD) was calculated, the reference price of each drug was taken and the cost per 100 bed-days was obtained. The average number of days that each patient received antiulcer medications and the costs of each drug were determined (market reference rate: € 1 per COP$ 2259.3 - July 2012).

The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Universidad Tecnológica de Pereira in the category of "research without risk," according to Resolution 8430/93 of Colombia's Ministry of Health and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data analysis was done using the statistical package SPSS-21.0 (IBM, USA) for Windows. Student's t test or ANOVA were used for comparisons of quantitative variables and χ2 for categorical variables. Bivariate analyses were conducted to establish statistical associations and logistic regression models were applied using inadequate antiulcer indication at admission and during hospitalization as dependent variables, and those that were significant in the bivariate analysis as independent variables. Statistical significance was predetermined to be p < 0.05.

Results

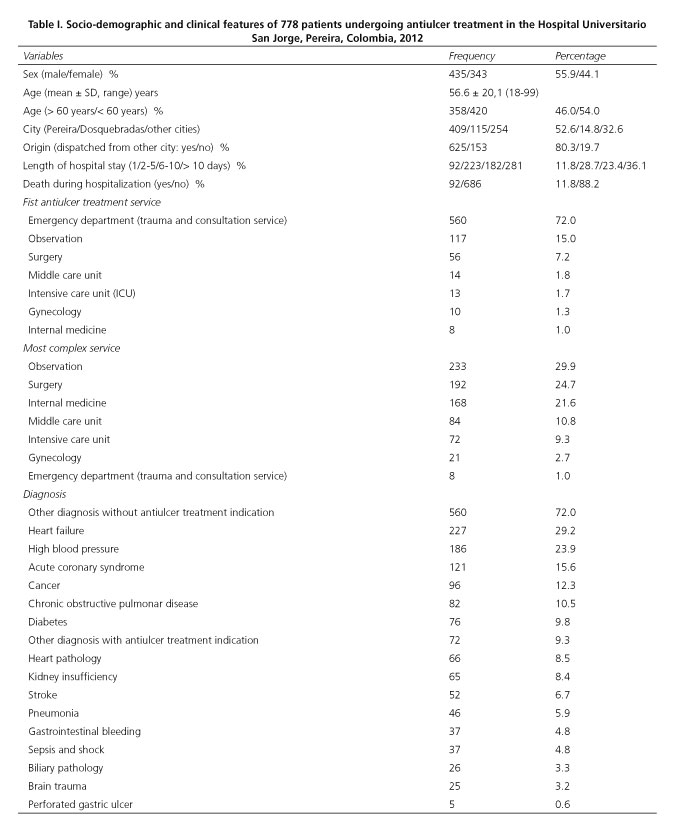

Of 853 inpatients 75 were discarded for having incomplete information, so the analysis was performed with 778patients. The socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of hospitalization of these patients can be seen in table I. There was a predominance of males, with an average hospital stay of 12.0 ± 15.7 days (range 1-200 days).

First antiulcer treatment

The most widely used antiulcer medication at the beginning of hospitalization was ranitidine in 438 patients (56.3%) followed by omeprazole in 332 cases (42.7%) and sucralfate in only 8 users (1.0%). No justification for the prescription of antiulcer treatments in 377 patients (48.5%) was found. The mean duration of the prescription was 8.7 ± 12.3 days (range: 0-131 days). Of these, 36.1% of patients (n = 281) received the antiulcer medication for more than ten days. Oral was the most frequent route of administration (n = 395, 50.8%).

The first antiulcer therapy was prescribed concomitantly with anticoagulants in 399 patients (51.3%), with antihypertensives in 397 cases (51.0%), and analgesics/antipyretics in 391 (50.2%), among other drugs. It was found that 42 patients (5.4%) concomitantly received another antiulcer medication. The frequency of use of antiulcer medications in patients with major polypharmacy was 419 cases (53.9%), followed by patients with minor polypharmacy in 202 cases (26.0%) and moderate in 157 (20.2%) patients.

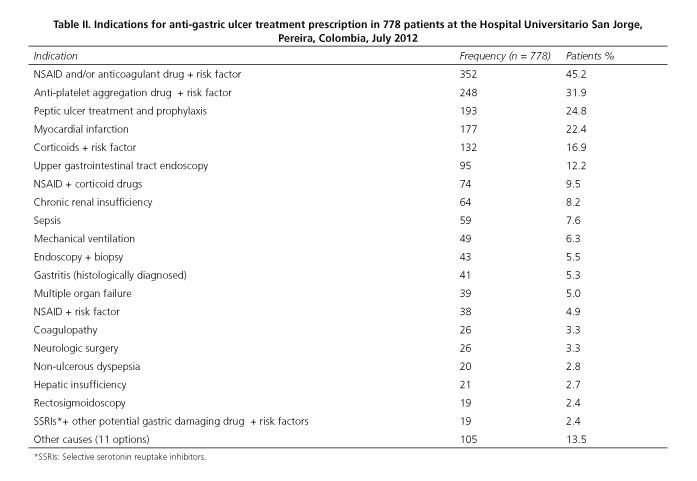

Indication-prescription of treatments with antiulcer medications

There were 554 patients (71.2%) who received only a single antiulcer therapy, but 224 (28.8% of cases) were given a new therapy with antiulcer medications at a different time in their hospitalization, 136 corresponding to omeprazole (60.7% of the patients), 73 to ranitidine (32.5%) and 15 to sucralfate (6.7%). Additionally, there were 74 patients (9.5% of total cases) whose antiulcer treatment was modified yet again during hospitalization, another 11 patients (1.4% of all cases) with a third modification, and finally 2 patients (0.2%) who either received 5 distinct antiulcer medications or with different routes of administration during hospitalization.

It was found that in 352 patients (45.2% of cases), the antiulcer medication was accompanied by the use of NSAIDs or anticoagulants with or without risk factors or in combination with other gastrolesive drugs. Furthermore, 248 patients (31.9%) were receiving anti-platelet agents. The antiulcer treatments were prescribed concomitantly with anticoagulants in 553 patients (71.0%), with antihypertensive drugs in 547 cases (70.3%), with analgesic-antipyretics in 498 (64.0%) and with opioids in 350 (45.0 %), among others. Table II shows the indications for which antiulcer treatment was initiated in patients.

Upon a search of all antiulcer medications during the course of hospitalization, the most prescribed was found to be ranitidine in 524 patients (67.3% of cases), followed by omeprazole in 491 patients (63.1%) and sucralfate in 39 patients (5.0%). It was determined that 336 (43.2%) of patients didn't have an appropriate indication during hospitalization. In addition, 95 patients (12.2%) received more than one antiulcer medication simultaneously.

Multivariate analysis

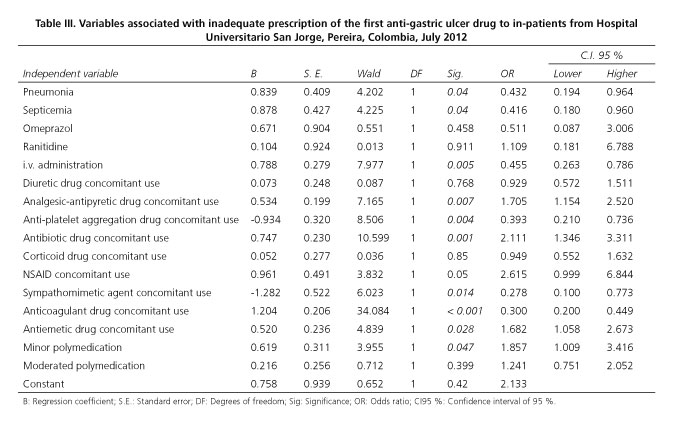

First antiulcer treatment

In a multivariate analysis of the misuse of initial antiulcer medications and the variables associated with statistically significant differences in the bivariate analysis, it was determined that giving the antiulcer medication concomitantly with an analgesic-antipyretic, other antibiotics different from beta-lactam, macrolides and tetracyclines, with antiemetics, or if the patient had minor polypharmacy, were all associated with a risk for improper prescription of antiulcer treatment. It was found that a diagnosis of pneumonia, sepsis, intravenous administration, anti-platelet agents, vasopressors and anticoagulants were all associated as protective factors for inappropriate prescription of antiulcer treatment (Table III).

Antiulcer treatment throughout hospitalization

A multivariate analysis between the inappropriate use of antiulcer medication during the course of hospitalization and the statistically significant variables in the bivariate analysis showed that concomitant administration of an analgesic was associated with an inappropriate prescription (Table IV). The intravenous route of administration, the use of anti-platelet or anticoagulant agents, or having a diagnosis of heart failure were associated as protective factors for inappropriate prescription of antiulcer medications.

Economic analysis

Oral omeprazole in 20 mg capsules was used at the rate of 11.0 DHD and the 40 mg injectable solution at 70 DHD, while 150 mg ranitidine tablets were used at 65.5 DHD and the injectable solution at 8.3 DHD.

The monthly cost for antiulcer treatments not indicated for all patients was € 3,335.6. The annual estimated cost for the improper prescription of antiulcer medications was € 16,770.0 DHD per 100 beds per day. Table V shows the economic analysis for each group of antiulcer medications according to their prescribed units, DHD and reference cost for each, as well as costs for oral and intravenous presentations.

Discussion

There was an inappropriate prescription in 48.5% of patients for the first antiulcer medication prescribed and in 43.2% of patients at the prescription throughout their entire hospitalization, accounting for an estimated unjustified annual cost of € 16,770 per 100 beds per day, establishing an association of risk with different variables for that inappropriate prescribing.

A significant unjustified use of antiulcer medications has been found, and variables and additional associated costs identified (19). Nardino et al. and various studies in countries like Saudi Arabia, the United States of America and Europe showed inadequate indications for antiulcer medications (PPI's and antiH2) that ranged between 40.0% and 73.0%, with variations in the health centers' care level and the populations studied. Other studies analyzed cases of stress ulcer prophylaxis, which showed 22.0% to 33.8% of prescriptions were inappropriate (20-26), or the unjustified formulation of antiulcer medication at the time of hospital discharge ranging from 24.0% to 69.0% (27,28), this being a new point of interest for future research. All these data on prescriptions are higher than those found in our population. Although most of these studies are old and based on evidence available at the time, the new scientific information on recommended use of antiulcer medications is one strength of this research regarding previous ones (20-28).

Additionally, indicators show there is a difficulty in retiring antiulcer prescriptions once initiated (29,30). In the United Kingdom, 51.0% of initial in-hospital prescriptions didn't have an adequate indication (30,31), a similar percentage to the one found in our work (48.5%); it was found that 5.3% of patients who initially received an unjustified antiulcer drug prescription subsequently had an indication during their hospitalization, while the remaining 43.2% still had no indication for their use.

The most prescribed drug was ranitidine, a finding that does not align with what can be found in the literature, where PPI's are on top (24,25,32,33). Nonetheless, we must mention that both oral and intravenous omeprazole were the antiulcer drugs with the highest accumulated cost in our study. It is also important to highlight the economic difference between oral and parenteral presentations, this difference representing an important point for intervention and one about which no literature can actually be found.

Guide implementation (such as the ones used in this work) has been shown to decrease drug prescriptions, inappropriate use and associated costs (34).

A study in the USA estimated annual savings of up to US$ 102,895 on patient care and US$ 11,333 on drug costs when stress-ulcer prophylaxis guides were use in an Intensive Care Unit (35), whilst a similar study in Canada demonstrated that daily drug costs were reduced from C$ 2.50/day to C$ 1.30/day by using these protocols (36). A study carried out by our research group showed that US$ 2,202,590 are wasted on unjustified PPI prescriptions in ambulatory care populations. These indicators allow comparisons among populations and hospitals, but are not described in the majority of studies (3).

Nardino et al. showed that university hospitals made more adequate antiulcer drug prescriptions, similar to the one in this study, when compared to other types of institution (20). We must mention that we included multiple diagnoses, procedures and treatments as an indication for antiulcer use; this might also have contributed to a reduced inappropriate use of antiulcer drugs in comparison to other studies (20-28).

Among this work's limitations it must be considered that this study does not allow analysis of the reasons for which health care professionals prescribed antiulcer drugs unless they made it obvious on the Medical History, so it cannot be assumed that the physicians formulated these drugs according to indications that were classified as reasonable.

To our knowledge this is the first study in Colombia and the region that analyzes the inappropriate prescription of antiulcer drugs, in this case hospital prescriptions, and is one of the few in the world to carry out an economic analysis of such behavior. The number of patients included (n = 778) greatly exceeds that of other described studies (24,26-28). New research should be carried out on antiulcer prescriptions after hospital discharge, and comparisons of adequate prescribing at university hospitals vs. non-academic hospitals, as well as evaluating the impact of implementing drug prescription guidelines (27,28,34,35). It is necessary to carry out more studies on the economic consequences of drug inadequate use, especially in the antiulcer group.

At our hospital (Hospital Universitario San Jorge) there was a lower rate of unjustified antiulcer drug prescriptions when comparing to other institutions; nonetheless, it is still high and alarming for the important costs incurred by the hospital to pay for medicines patients do not need; also, even though an initial prescription was unjustified, very few of the antiulcer drug therapies were suspended during the whole stay in the hospital.

The new information learned must be used to modify hospital prescription practices and implement changes/strategies that improve patient security and allow better and more economical use of resources. It is necessary that all related works determine economic indicators such as DHD and cost per 100 beds per day that will allow other researchers to make comparisons among different populations and hospitals. Some authors have proposed intervention measures for this problem, with the best results shown by adhesion to clinical practice guidelines and evidence-based protocols (7,37,38).

References

1. Cahir C, Fahey T, Tilson L, Teljeur C, Bennett K. Proton pump inhibitors: Potential cost reductions by applying prescribing guidelines. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:408. [ Links ]

2. Ajumobi AB, Vuong R, Ahaneku H. Analysis of nonformulary use of PPIs and excess drug cost in a Veterans Affairs population. J Manag Care Pharm 2012;18:63-7. [ Links ]

3. Sánchez-Cuén JA, Irineo-Cabrales AB, Bernal-Magaña G, Peraza-Garay FJ. Inadequate prescription of chronic consumption of proton pump inhibitors in a hospital in Mexico. Cross-sectional study. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2013;105:131-7. [ Links ]

4. Martín-Echevarría E, Pereira Juliá A, Torralba M, Arriola Pereda G, Martín Dávila P, Mateos J et al. Assessing the use of proton pump inhibitors in an internal medicine department. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2008;100:76-81. [ Links ]

5. Lin PC, Chang CH, Hsu PI, Tseng PL, Huang YB. The efficacy and safety of proton pump inhibitors vs. histamine-2 receptor antagonists for stress ulcer bleeding prophylaxis among critical care patients: A meta-analysis. Crit Care Med 2010;38:1197-205. [ Links ]

6. Gisbert JP, González L, Calvet X, Roqué M, Gabriel R, Pajares JM. Proton pump inhibitors versus H2-antagonists: A meta-analysis of their efficacy in treating bleeding peptic ulcer. Aliment PharmacolTher 2001;15:917-26. [ Links ]

7. Ponce J, Esplugues JV. Rationalizing the Use of PPIs: An Unresolved Matter. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2013;105:121-4. [ Links ]

8. Ibáñez A, Alcalá M, García J, Puche E. Drug-drug interactions in patients from an internal medicine service. Farm Hosp 2008;32:293-7. [ Links ]

9. Heidelbaugh JJ, Kim AH, Chang R, Walker PC. Overutilization of proton-pump inhibitors: What the clinician needs to know. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2012;5:219-32. [ Links ]

10. Parikh N, Howden CW. The safety of drugs used in acid-related disorders and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2010;39:529-42. [ Links ]

11. Ntaios G, Chatzinikolaou A, Kaiafa G, Savopoulos C, Hatzitolios A, Karamitsos D. Evaluation of use of proton pump inhibitors in Greece. Eur J Intern Med 2009;20:171-3. [ Links ]

12. Papis S. Análisis de la Relevancia Sanitaria y Económica en la Prescripción de Antiulcerosos del Grupo de los Prazoles. Acta Farm Bonaerense 2006;25:283-8. [ Links ]

13. Collazo M, Haedo W. Aplicación de la farmacoeconomía a los resultados de la medicación para la curación de las úlceras pépticas. Rev Cubana Farm 2000;34:175-80. [ Links ]

14. Machado-Alba J, Fernández A, Castrillón J, Campo C, Echeverri L, Gaviria A, et al. Prescribing patterns and economic costs of proton pump inhibitors in Colombia. Colomb Med 2013;44:13-8. [ Links ]

15. Soto-Álvarez. J. Estudios de farmacoeconomía: ¿por qué, cómo, cuándo y para qué? Medifam 2001;11:147-55. [ Links ]

16. Unidad Docente de Medicina Familiar y Comunitaria Sector Zaragoza I-Grupo de Trabajo Sector Zaragoza I. Guía De Práctica Clínica de Empleo de los Inhibidores de la Bomba de Protones en la Prevención de Gastropatías Secundarias a Fármacos 2012. (Consultado: Julio 2013) Disponible en: http://www.guiasalud.es/GPC/GPC_509_IBP_gastropatias_2rias_fcos_completa.pdf. [ Links ]

17. National Prescribing Service. Proton pump inhibitors in primary care. Prescribing Practice Review. (Consultado: Julio 2013) Disponible en: http://www.nps.org.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/23745/ppr34_PPIs_ulcer_0906.pdf. [ Links ]

18. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP Therapeutic Guidelines on Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis. ASHP Commission on Therapeutics and approved by the ASHP Board of Directors on November 1998. Am J Health Syst Pharm 1999;56:347-79. [ Links ]

19. Eid SM, Boueiz A, Paranji S, Mativo C, Landis R, Abougergi MS. Patterns and predictors of proton pump inhibitor overuse among academic and non-academic hospitalists. Intern Med 2010;49:2561-8. [ Links ]

20. Nardino RJ, Vender RJ, Herbert PN. Overuse of acid-suppressive therapy in hospitalized patients. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:3118-22. [ Links ]

21. Zink DA, Pohlman M, Barnes M, Cannon ME. Long-term use of acid suppression started inappropriately during hospitalization. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005;21:1203-9. [ Links ]

22. Mayet AY. Improper use of antisecretory drugs in a tertiary care teaching hospital: An observational study. Saudi J Gastroenterol 2007;13:124-8. [ Links ]

23. Gupta R, Garg P, Kottoor R, Munoz JC, Jamal MM, Lambiase LR, et al. Overuse of acid suppression therapy in hospitalized patients. South Med J 2010;103:207-11. [ Links ]

24. Sheikh-Taha M, Alaeddine S, Nassif J. Use of acid suppressive therapy in hospitalized non-critically ill patients. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2012;3:93-6. [ Links ]

25. Heidelbaugh JJ, Goldberg KL, Inadomi JM. Overutilization of proton pump inhibitors: A review of cost-effectiveness and risk. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104(Supl.2):S27-32. [ Links ]

26. Heidelbaugh JJ, Inadomi JM. Magnitude and economic impact of inappropriate use of stress ulcer prophylaxis in non-ICU hospitalized patients. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:2200-5. [ Links ]

27. Wohlt PD, Hansen LA, Fish JT. Inappropriate continuation of stress ulcer prophylactic therapy after discharge. Ann Pharmacother 2007;41:1611-6. [ Links ]

28. Thomas L, Culley EJ, Gladowski P, Goff V, Fong J, Marche SM. Longitudinal analysis of the costs associated with inpatient initiation and subsequent outpatient continuation of proton pump inhibitor therapy for stress ulcer prophylaxis in a large managed care organization. J Manag Care Pharm 2010;16:122-9. [ Links ]

29. Noguerado A, Rodríguez R, Zelaya P, Sánchez A, Antuña F, Lutz E, et al. Utilización de supresores de la secreción ácida en pacientes hospitalizados. An Med Interna 2002;19:557-60. [ Links ]

30. Ramirez E, LeiSH, Borobia AM, Piñana E, Fudio S, Muñoz R, et al. Overuse of PPIs in patients at admission, during treatment, and at discharge in a tertiary Spanish hospital. Curr Clin Pharmacol 2010;5:288-97. [ Links ]

31. McGowan B, Bennett K, Tilson L, Barry M. Cost effective prescribing of proton pump inhibitors (PPI's) in the GMS Scheme. Ir Med J 2005;98:78-80. [ Links ]

32. Pavlides M, Wilcock M, Murray I. PPI prescribing and dosage: can hospitals help primary care? Prescriber 2007;18:41-5. [ Links ]

33. Forgacs I, Loganayagam A. Overprescribing proton pump inhibitors. BMJ 2008;336:2-3. [ Links ]

34. Khalili H, Dashti-Khavidaki S, HosseinTalasaz AH, Tabeefar H, Hendoiee N. Descriptive analysis of a clinical pharmacy intervention to improve the appropriate use of stress ulcer prophylaxis in a hospital infectious disease ward. J Manag Care Pharm 2010;16:114-21. [ Links ]

35. Mostafa G, Sing RF, Matthews BD, Pratt BL, Norton HJ, Heniford BT. The economic benefit of practice guidelines for stress ulcer prophylaxis. Am Surg 2002;68:146-50. [ Links ]

36. Lampen-Smith A, Young J, O'Rourke MA, Balram A, Inns S. Blinded randomized controlled study of the effect of a discharge communication template on proton pump inhibitor prescribing. N Z Med J 2012;125:30-6. [ Links ]

37. Judd, WR, Davis GA, Winstead PS, Steinke DT, Clifford TM, Macaulay TE. Evaluation of continuation of stress ulcer prophylaxis at hospital discharge. Hosp Pharm 2009;44:888-93. [ Links ]

38. Westbrook JI, Duggan AE, McIntosh JH. Prescriptions for antiulcer drugs in Australia: Volume, trends, and costs. BMJ 2001;323:1338-9. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Jorge Enrique Machado-Alba

Health Sciences Faculty

Programa de Medicina

Universidad Tecnológica de Pereira

Paraje la Julita, Pereira, Risaralda, Colombia

AA: 97-Zip code: 660003

e-mail: machado@utp.edu.co

Received: 14-10-2013

Accepted: 09-01-2014

texto en

texto en