Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.106 no.6 Madrid jun. 2014

ORIGINAL PAPERS

Lactose tolerance test shortened to 30 minutes: An exploratory study of its feasibility and impact

Test de tolerancia a la lactosa reducido a 30 minutos: un estudio exploratorio de su factibilidad e impacto

José Luis Domínguez-Jiménez1, Antonio Fernández-Suárez2, Sara Ruiz-Tajuelos1, Juan Jesús Puente-Gutiérrez1 and Antonio Cerezo-Ruiz3

1Department of Digestive Diseases and 2Biotechnology Area. Hospital Alto Guadalquivir de Andújar. Jaén, Spain.

3Hospital Alta Resolución Sierra Segura, Alcaudete y Puente Genil. Jaén, Spain

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Lactose malabsorption (LM) is a very common condition with a high prevalence in our setting. Lactose tolerance test (LTT) is a basic, affordable test for diagnosis that requires no complex technology. It has been recently shown that this test can be shortened to 3 measurements (baseline, 30 min, 60 min) with no impact on final results. The purpose of our study was to assess the feasibility and benefits of LTT simplification and shortening to 30 min, as well as the financial impact entailed.

Material and methods: A multicenter, observational study of consecutive patients undergoing LTT for LM suspicion. Patients received 50 g of lactose following a fasting period of 12 h, and had blood collected from a vein at all 3 time points for the measurement of blood glucose (mg/dl). Differences between the shortened and complete test forms were analyzed using McNemar's test. A comparison of blood glucose levels between patients with normal and abnormal results was performed using Student's T-test for independent mean values. Consistency was assessed using the kappa index. A p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results: A total of 270 patients (69.6% females) were included, with a mean age of 39.9 ± 16 years. LTT was abnormal for 151 patients (55.9%). We observed no statistically significant differences in baseline blood glucose levels between patients with normal and abnormal LTT results (p = 0.13); however, as was to be expected, such differences were obvious for the remaining time points (p < 0.01). Deleting blood glucose measurements at 60 minutes only led to overdiagnose LM (false positive results) in 6 patients (2.22 %), with a kappa index of 0.95 (95% CI: 0.92-0.99) (p < 0.001) versus the complete test. Suppressing measurements at 60 min would have saved at least € 7,726.

Conclusion: The shortening of LTT to only 2 measurements (baseline and 30-min) hardly leads to any differences in final results, and would entail savings in time, materials, and personnel.

Key words: Malabsorption syndromes. Lactose. Lactose tolerante test. Lactose intolerance.

RESUMEN

Introducción: la malabsorción a la lactosa (ML) es una patología muy frecuente con alta prevalencia en nuestro medio. El test de tolerancia a la lactosa (TTL) es una prueba básica y económica que permite su diagnóstico sin precisar tecnología compleja. Recientemente se ha demostrado que este test puede reducirse a 3 determinaciones (basal, 30 y 60 min) sin afectar al resultado final. El propósito de nuestro estudio fue el valorar la factibilidad y ventajas de poder acortar y simplificar el TTL a 30 min, así como el impacto económico que conllevaría.

Material y métodos: estudio multicéntrico y observacional de pacientes consecutivos a los que se les realiza un TTL ante la sospecha de ML. Los enfermos reciben 50 g de lactosa tras 12 h de ayuno y se les realiza extracción de sangre venosa en los 3 tiempos para la medición de la glucemia (mg/dl). La diferencia entre el test reducido y el completo se analizaron con el test de McNemar. La comparación de los niveles de glucemia entre los pacientes con test normal y patológico fue realizada usando el test t-Student para comparación de medias independientes. La concordancia fue evaluada con el índice Kappa. Se consideró p < 0,05 como estadísticamente significativo.

Resultados: se incluyeron 270 pacientes (69,6 % mujeres) con edad media de 39,9 ± 16 años. El TTL fue patológico en 151 casos (55,9 %). No observamos diferencias estadísticamente significativas entre las glucemias basales de los pacientes con TTL normal o patológico (p = 0,13), sin embargo, como cabía esperar, estas diferencias fueron evidentes en los demás tiempos (p < 0,01). La eliminación de la determinación de glucemia a los 60 min tan solo sobrevaloró el diagnóstico de ML (falsos positivos) en 6 enfermos (2,22 %), con índice kappa de 0,95 (IC 95 %: 0,92-0,99) (p < 0.001) respecto al test completo. Si se hubiera suprimido la determinación de los 60 min, se podría haber ahorrado al menos 7.726 euros.

Conclusión: el reducir el TTL a 2 determinaciones (basal y 30 min) no implica apenas cambios en el resultado final del test, sin embargo conllevaría un ahorro de tiempo, material y personal.

Palabras clave: Síndromes de malabsorción. Lactosa. Prueba de tolerancia a la lactosa. Intolerancia a la lactosa.

Introduction

Lactose malabsorption (LM) is a very common condition; its frequency varies according to population ethnics, with a low prevalence in Northern European countries (< 5 %) as compared to Southern European (70-80 %) and Southeast Asian ones (approaching 100 %) (1,2).

Most common clinical symptoms include abdominal pain, diarrhea, bloating, flatulence, and vomiting following the ingestion of milk or milk-containing products (3). However, this sugar's malabsorption does not always translate into lactose intolerance (LI); in fact, only between one third and half of patients with LM are also lactose intolerants (1).

Different approaches are available for the diagnosis of LM, from lactase activity measurement in jejunal biopsy to absorption tests (lactose overload), through malabsorption studies (lactose hydrogen breath test, LHBT) and fecal analysis (fecal pH) (4). A novel method was recently developed for the diagnosis of lactose malabsorption -the gaxilose test- with promising results (5,6).

A lactose tolerance test (LTT) is a basic test of widespread use in county hospitals, high-resolution hospitals, and health centers because of its low cost and lack of complex infrastructure requirements. It consists of blood glucose measurements at different times following the ingestion of 50 g of lactose (baseline, 30, 60, 120 minutes). Drawbacks include potential symptoms (pain, diarrhea, flatulence, vomiting), its relatively invasive nature (multiple blood draws), and a prolonged duration (120 minutes) (7).

In the last few years industrial countries have pointed out a long-standing issue, namely the progressively increasing limitation of resources allotted for health care. Knowing which options -among all those available- will be more efficient (will yield better clinical results with lower associated costs) is important, and will result in greater therapy benefits with a lower cost (8).

Studies have been recently published showing that measurements at 120 min contribute nothing to LTT results, hence testing may be shortened to 60 min (9,10). We have seen that LTT may be further shortened with no significant changes in its results. This would entail reduced costs and time. The main goal of our study was to assess the feasibility and benefits of a simplified LTT shortened to 30 min, as well as its associated financial impact.

Material and methods

Subjects

A multicenter, observational, cross-sectional study in a series of consecutive patients -from November 2011 to September 2012- with ≤ 16 years of age who underwent an oral lactose overload test for clinically suspected lactose intolerance (abdominal symptoms after exposure to dairy products or, when such association is unknown, presence of dysmotility, diarrhea or vomiting). Patients from the Andalusian Agencia Sanitaria Alto Guadalquivir (ASAG) hospitals in Andújar, Montilla, Sierra de Segura, Alcaudete, Alcalá la Real, and Puente Genil were included. Agencia Sanitaria covers a population of 253,000 inhabitants. Exclusion criteria included a history of celiac disease, hyperthyroidism/hypothyroidism, active inflammatory bowel disease, recent antibiotic/probiotic therapy (< 30 days), recent use of proton pump inhibitors/prokinetic agents (< 7 days), major abdominal surgery, drinking < 60 g alcohol a day, and diabetes mellitus (DM). Patients were withdrawn from the study if newly diagnosed with any of these conditions during the study.

All patients gave their consent before any exams were performed.

Design

Patients received a predefined lactose-free diet (LFD) for 7 days. Then they underwent LTT after being administered 50 g/250 mL lactose (Lactonaranja®, Bioanalitica SL, Spain) under fasting conditions, with blood draws from a vein at baseline, 30, and 60 min to measure blood glucose levels (mg/dL) using a Cobas® 8000 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). LTT 60 was defined as testing for all three time points, and LTT 30 was defined as testing with no measurements at 60 min. The test was deemed abnormal (malabsorption) when glucose levels increased ≤ 20 mg/mL from baseline at any time point, this being the most widely accepted cut-off. Reproducibility was not affected by test shortening as the measurement protocol remains unchanged.

Lab measurements also included CBC, immunoglobulin A, anti-transglutaminase IgA antibodies, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) in order to identify potential exclusion criteria.

Financial analysis

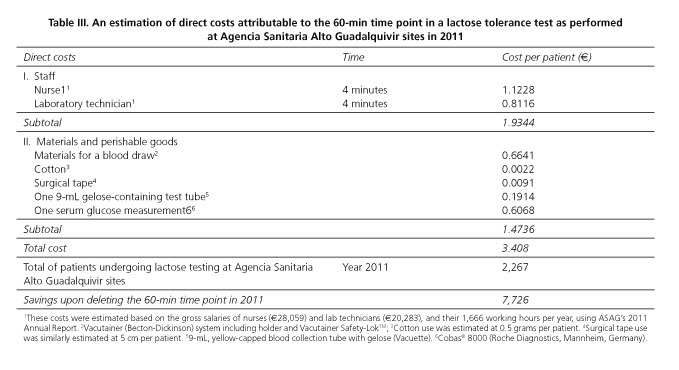

The direct costs of an additional blood draw were estimated including both perishable materials (needles, vacuum systems, chemistry tubes, cotton swabs, surgical tape) and staff (nurses and lab technicians). Indirect costs derived from patient's lost time or in connection with false positive or false negative results -which prompt unnecessary additional testing (false positives) or repeat testing for symptom persistence in the absence of preventive actions (false negatives)- were not included.

Statistical method

Sample size was obtained using the GRANMO 7.12 software (IMIM Hospital del Mar, Barcelona, Spain); endorsing an alpha risk of 0.05 and a beta risk of 0.2 in a bilateral contrast, 205 subjects are required to detect a difference equal to or greater than 0.1 units, assuming a proportion of 0.45 in the reference group. A rate of 5 % losses to follow-up was estimated. Differences between LTT 60 and LTT 30 were analyzed using McNemar's test for two paired proportions. Agreement degree between LTT 60 and LTT 30 was measured using the kappa index and related 95 % confidence intervals. Differences in blood glucose level between patients with abnormal and normal test results were established using Student's T-test for independent means. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The statistical analysis was carried out with the SPSS 16.0® software (SPSS, Inc., USA).

Results

A total of 277 patients were enrolled in the study, and seven of these were excluded because of their meeting exclusion criteria (5 with type 2 DM, 1 with hypothyroidism, and 1 with adult celiac disease). All patients were Caucasians with a mean age of 39 ± 16 years; 69.6 % were women.

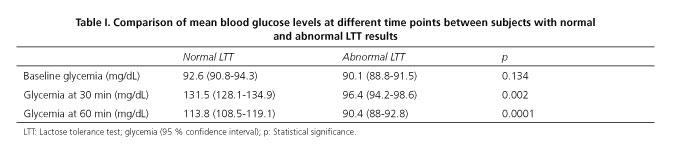

In all, 151 patients (55.9 %) had an abnormal LTT. Study-prompting symptoms included abdominal pain (65.6 %), bloating (50.4 %), diarrhea (50.4 %), vomiting (10.4 %), and stomach rumble (21.5 %). No statistically significant differences in baseline glycemia were spotted between patients with normal and abnormal LTT results, but such differences were seen (as expected) at different time points (Table I).

Test result interpretation was changed for 6 patients (2.22 %) (McNemar's test: p = 0.03) when the 60-min time point was deleted. Table II illustrates diagnostic differences between LTT 30 and LTT 60, with their related agreement degree.

Table III shows an estimation of direct costs for a single time point measurement (60 min) in ASAG sites. During 2011, a total of 2,267 LTTs were carried out in ASAG sites; deletion of the 60-min time point during LTT procedures would have yielded savings of € 7,726, approximately, in direct costs.

Discussion

Several methods exist for the diagnosis of lactose malabsorption (LM). The measurement of lactase activity in jejunal biopsies has been proposed as gold standard (11). However, this is a much too aggressive test for the study of a mild condition, with results that may be influenced by irregular lactase activity distribution along the small bowel mucosa (1). Lactose hydrogen breath test (LHBT) represents the most commonly used indirect method for the diagnosis of LM as it is a non-invasive, reliable, inexpensive option (12). Sensitivity is very good (77.5 % on average) and specificity is excellent (97.6 % on average) (13). However, in addition to requiring 240 minutes for completion, false negatives are possible given the inability of the intestinal flora to release H2 following the ingestion of non-absorbable carbohydrates or recently administered antibiotics, as well as false positives because of bacterial overgrowth. Shortened LHBTs (only 180 min) have been validated for the screening of lactose malabsorption when high-dose lactose is used for overload (14). Of late, a genetic test is available based on the detection of DNA polymorphism C/T-13910, whose C/C variant presents a strong correlation with poor lactase activity; however, drawbacks include a high cost and the lack of clinical information provided by lactose exposure (15).

Although LHBT is the most widespread approach, and the one supported with the highest number of literature references, many hospitals and outpatient clinics lack the necessary equipment, hence they are still using LTT on an ongoing basis. This is a minimally invasive test requiring 120 minutes for completion, with a sensitivity of 75 % and a specificity of 96 % in the adult (17). False negative results occur in patients with diabetes, bacterial overgrowth, and delayed gastric emptying. Two studies were recently reported, which show how suppressing measurements at 120 min has no impact whatsoever on test results (9,10); it is for this reason that our sites opted to implement an LTT variant shortened to 60 min.

In our results we saw that excluding glycemia measurements at 60 minutes results in a proportion of identified cases that remains virtually unchanged as compared to the complete procedure (only 2.22 % of false positives), with very high agreement and consistency levels (kappa index). Such data are comparable to those from the study by van Rossum HH et al. (10) in a Dutch population, with a false positive rate of 3 %. Furthermore, in various studies in India, the diagnostic efficacy of LTT 30, as measured with capillary samples, is very high when genetic testing is used as the gold standard (S 96.6 %, Sp 88.6 %, PPV 96.6 %, NPV 94.8 %) (16-17), and higher when 50 g rather than 25 g of lactose are used (18).

Financial assessments in the health setting are aimed at comparing the impact of an intervention on the health status of affected individuals versus its repercussions on resource use. A clear economical benefit has been shown to result from boiling down traditional LTT (120 min) to shortened LTT (60 min) (9). Deleting another time point in LTT hardly involves any changes in terms of patient health since clinical outcomes are similar to those obtained when using full-length LTT, and more sensitive, specific tests may also be run for doubtful diagnoses.

Among study limitations the fact that LTT 30 was not compared to the gold standard should be highlighted, as it implies that this technique could not be validated for the diagnosis of lactose malabsorption with an estimation of diagnostic effectiveness. Regarding our analysis of direct costs as related to the deletion of one glycemic time point, our estimations are highly simplified, and indirect costs were not calculated given their complexity. Therefore, other potentially intervening factors were overlooked, including those derived from additional unnecessary testing (false positives) or repeat testing for symptom persistence in the absence of preventive actions (false negatives), patient's lost time, etc.

Future, well-structured studies comparing LTT 30 with the gold standard (jejunal biopsy) or other highly sensitive, highly specific validated techniques (e.g., gaxilose test) are needed to validate its diagnostic efficacy for lactose malabsorption.

A shortened LTT obviously benefits patients with one less draw and reduced waiting time; it similarly benefits the health system by saving up on time, personnel, and materials. Also, while the goal of the present study was not to compare LTT 30 versus other diagnostic methods, the fact that the time required for test completion would be one eighth of the standard LHBT length (240 minutes) must be underscored. Moreover, in contrast to genetic testing and lactase activity in duodenal biopsies, LTT provides patients with lactose overloads, which may result in valuable clinical information. Therefore, based on the above data, LTT 30 has some economic advantages over LTT 60, and their diagnostic consistency is high.

References

1. Usai-Satta P, Scarpa M, Oppia F, Cabras F. Lactose malabsorption and intolerance: what should be the best clinical management? World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2012;3:29-33. [ Links ]

2. Rao DR, Bello H, Warren AP, Brown GE. Prevalence of lactose maldigestion. Influence and interaction of age, race and sex. Dig Dis Sci 1994;39:1519-24. [ Links ]

3. Suarez FL, Savaiano DA, Levitt MD. A comparison of symptoms after the consumption of milk or lactose-hydrolyzed milk by people with self-reported severe lactose intolerance. N Engl J Med 1995;333:1-4. [ Links ]

4. Johnson AO, Semenya JG, Buchowski MS, Enwonwu CO, Scrimshaw NS. Correlation of lactose maldigestion, lactose intolerance, and milk intolerance. Am J Clin Nutr 1993;57:399-401. [ Links ]

5. Hermida C, Guerra P, Martínez-Costa OH, Sánchez V, Sánchez JJ, Solera J, et al. Phase I and phase IB clinical trials for the noninvasive evaluation of intestinal lactase with 4-galactosylxylose (Gaxilose). J Clin Gastroenterol 2013;47:501-8. [ Links ]

6. Aragón JJ, Hermida C, Martínez-Costa OH, Sánchez V, Martín I, Sánchez JJ, et al. noninvasive diagnosis of hypolactasia with 4-galactosylxylose: a multicentre, open-label, phase iib-iii nonrandomized trial. J Clin Gastroenterol 2014;48:29-36. [ Links ]

7. Shaw A, Davies G. Lactose intolerance: Problems in diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Gastroenterol 1999;28:208-16. [ Links ]

8. Sacristán JA, Soto J, Reviriego J, Galende I. Pharmacoeconomics: The calculation of efficiency. Med Clin 1994;103:143-9. [ Links ]

9. Domínguez-Jiménez JL, Fernández-Suárez A. Can we shorten the lactose tolerance test? Eur J Clin Nutr 2014;68:106-8. [ Links ]

10. van Rossum HH, van Rossum AP, van Geenen EJ, Castel AD. The one hour lactose tolerance test. Clin Chem Lab Med 2013;51:201-3. [ Links ]

11. Newcomer AD, McGill DB, Thomas PJ, Hofmann AF. Prospective comparison of indirect methods for detecting lactase deficiency. N Eng J Med 1975;293:1232-6. [ Links ]

12. Hermans M, Brummer R, Ruijgers A, Stockbrügger R. The relationship between lactose tolerance test results and symptoms of lactose intolerance. Am J Gastroenterol 1997;92:981-4. [ Links ]

13. Gasbarrini A, Corazza GR, Gasbarrini G, Montalto M, Di Stefano M, Basilisco G, et al. Methodology and indications of H2-breath testing in gastrointestinal diseases: the Rome Consensus Conference. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;29(Supl. 1):1-49. [ Links ]

14. Casellas F, Malagelada JR. Applicability of short hydrogen breath test for screening of lactose malabsorption. Dig Dis Sci 2003;48:1333-8. [ Links ]

15. Schirru E, Corona V, Usai-Satta P, Scarpa M, Oppia F, Loriga F, et al. Genetic testing improves the diagnosis of adult type hypolactasia in the Mediterranean population of Sardinia. Eur J Clin Nutr 2007;61:1220-5. [ Links ]

16. Babu J, Kumar S, Babu P, Prasad JH, Ghoshal UC. Frequency of lactose malabsorption among healthy southern and northern Indian populations by genetic analysis and lactose hydrogen breath and tolerance tests. An J Clin Nutr 2010;91:140-6. [ Links ]

17. Gupta D, Ghoshal UC, Misra A, Misra A, Choudhuri G, Singh K. Lactose intolerance in patients with irritable bowel syndrome from northern India: A case-control study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;22:2261-5. [ Links ]

18. Ghoshal UC, Kumar S, Misra A, Mittal B. Lactose malabsorption diagnosed by 50g dose is inferior to assess clinical intolerance and to predict response to milk withdrawal than 25g dose in an endemic area. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;28:1462-8. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

José Luis Domínguez Jiménez.

Department of Digestive Diseases.

Hospital Alto Guadalquivir.

Avda. Blas Infante, s/n.

23740 Andújar, Jaén. Spain

e-mail: jldominguezjim@hotmail.com

Received: 28-03-2014

Accepted: 07-07-2014

texto en

texto en