INTRODUCTION

Less than 3 % of malignant oral and maxillary lesions are metastases. Primary infraclavicular solid tumours that most commonly spread to head & neck are from epithelial strain and lung or breast origin. Most frequently affected regions are the attached gingiva in regard to oral soft tissues, and the mandible in the molar area in regard to bones. Typical reasons for consultation are an exophytic nodule or mass, with bleeding tendency, inflammation, pain or sensory disturbance1,2.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Our work centre is a tertiary level hospital, which covers about a 385.000 population area in relation to Oral & Maxillofacial public assistance. Every patient with a malignant tumour diagnosis in our department is included in a clinical session of our own and a multidisciplinary one. A complete review of the session records is performed, from January 2003 to December 2018. This study is retrospective of a standard diagnosis and treatment praxis, so institutional review board approval was exempt. 21 cases of metastatic lesions located in soft tissue of the mouth and/or maxillary bones are found. Excluding criteria are: less than 18-year-old; metastases located in the skin, salivary glands, other craniofacial bones and exclusive cervical lymph-node affectation; lymphoproliferative disorders; and not-known origin.

Epidemiologic data, general potentially carcinogenic and personal health records (PHR), first-degree relative oncologic processes, current disease, neoplasm strain and origin, treatment and follow-up data are collected.

In relation to toxic habits, tobacco abuse is considered in three levels: less or equal than 5 pack-years (+), between more than 5 and less or equal than 15 pack-years (++), and more than 15 pack-years (+++). In similar way, alcohol use is codified in other three levels: less or equal than 2 alcohol units/day (+), between more than 2 and less or equal than 8 units/day (++), and more than 9 units/day (+++). In relation to PHR, usual cardiovascular risk factors are considered (hypertension, type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia). Cardiologic records include arrhythmias, ischemic heart disease, valvulopathies and other miocardiopathies. Pulmonary records cover chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, obstructive sleep apnoea, lung infection sequels (basically tuberculosis) and other fibrous lung disorders. Gastrointestinal records include oesophageal reflux disease, peptic ulcer, diverticles, benign adenomas, and infectious, alcoholic or autoimmune hepatic diseases. Endocrine records cover goitre and other thyroid affections, osteoporosis and other metabolic bone conditions. Genitourinary records include hyperuricemia, chronic renal failure and other nephropathies, endometriosis and ovary cysts. Even other general background data could be collected, it was not considered for the present study to not overburden it with irrelevant information.

Furthermore, any treatment which involves osteonecrosis as an adverse effect was specifically collected.

A retrospective descriptive analysis of frequencies is carried out with the Microsoft Excel(r) 2007 software.

RESULTS

There are 17 unreported cases while case number 11, 12, 13 and 20 have been published before as case-reports3,4. 12 patients are males and 9 females, with mean age of 62.9 years-old, 52-82 range. All of them are white-caucasians. In relation to PHR, 19.0 % of the patients have a potentially carcinogenic occupational exposure, every one of them from lung origin. 52.4 % refer some kind of tobacco abuse, 61.9 % alcohol use and no one other substance abuse. 9.5 % have some drug-related allergy reported. One or more cardiovascular risk factor are known in 57.1 %, cardiologic records in 19.0 %, pulmonary in 28.6 %, gastrointestinal in 19.0 %, endocrine in 19.0 % and genitourinary in 14.3 %. 9.5 % suffered other malignant tumour different from the current one, and 23.8 % have a first-degree relative with a neoplasm. 33.3 % patients, due to oncologic process, have received treatment with bisphosphonates or other osteonecrosis-related drugs, or received craniofacial radiotherapy (Table 1).

The metastasis is the malignancy debut in 7 patients. It corresponds to infirmity progression in 14, only 2 of them without previous stage IV, with range of 1-252 months from the first oncologic diagnosis. The reason of consultation is a mass in 66.7 %, nodule 14.2 %, temporo-mandibular joint dysfunction 4.8 % and scheduled examination finding (periostitis in computed tomography and high uptake in scintigraphy) 9.5 %. Localization is soft tissue in 8 patients and the maxilla, the mandible or both in 13 (Figure 1). 81.0 % neoplasms are from epithelial lineage, 9.5 % melanoma and 9.5 % sarcoma. 23.8 % of the tumours originated in the lung, 23.8 % breast, 23.8 % kidney, 9.5 % skin, 9.5 % soft parts, 4.8 % prostate and 4.8 thyroid (Figure 2). Oncogene studies, available in 4 patients, reveal 2 ERRB2 positive cases, both of them from breast origin. All of the patients have at some point of the evolution metastases in other localizations, highlighting bones (66.7 %) and lungs (56.3 %), excluding the primary ones of these regions (Table 2).

The maxillofacial metastasis treatment is surgery in 14.3 %, radiotherapy 38.1 %, chemo-/immune-/biological therapy in 47.6 % and just symptomatic treatment in 28.6 %, which coincides with those patients who die before less than 5 months after the metastasis diagnosis. Follow-up ranges from 1 to 124 months. 17 patients die, 2 of the living have stable infirmity, 1 is in progression and 1 has no evidence of disease. Taking in account those patients who still are alive, the main survival is 23.0 months (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Metastasis is the main cause of morbidity and mortality in most oncologic patients. Almost any malignant tumour could disseminate to the head and neck. Most common primary sites differ between genders and geographic area, mainly between Eastern and Western series. This fact may reflect differences in the prevalence of primary tumours and indirectly oncologic risk factors, genetics and lifestyles. Most reported cases in the literature are from United States of America, inserting an important geographic bias5,6.

A literature review of recent similar single/double institution case-series as ours is performed, with more than 15 cases and a 10-year period minimum (Table 3) 5,7,8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18-19. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are very heterogeneous. Two series only focus in one region7,15. Several of them consider other maxillofacial regions for metastasis target, such as the parotid gland, head & neck skin and cervical lymph-nodes, apart from oral soft tissues and jaws. We reported metastases from solid tumours including melanocytic origin, while other studies include lymphoproliferative disorders and not-known primary cancer localization neither histology. Men are more prevalent than women in all the series except one from Brazil14. Mean age is between the 5th and 7th decades, but oral metastases could develop at any age. Some studies consider for their analysis children versus adults, because of radically different lineage, origin and better prognosis in the first ones17. Most common tissue lineage of solid tumours is epithelial, carcinomas or and adenocarcinomas, in all the series. Regarding the metastasis source, it is lung or breast in Western countries while it stands out lung or liver in the Eastern ones. Except ours and other one from France15, mean survival of solid tumours is equal or less than 16 months in all the series. One of the main differences of our study from all the others is the inclusion of detailed background of the patients.

Tumour cells have unique heterogeneous and plasticity properties due to innate and acquired accumulated mutations. Before a metastatic lesion is established, sequential steps happen, known as the invasion-metastasis cascade. They are: penetration through the extracellular matrix (ECM) from the primary tumour, intravasation into the vessels, circulation until settlement in the microvasculature target organ, extravasation, invasion of the underlying EMC, and angiogenesis processes. Highly perfused organs, such as the lung capillary network, are usual locations where circulating tumour cells could be passively trapped. Inflammatory microenviroment could help to engraft and proliferate. Bone marrow with its stromal cells, chemokines, integrins and other pro-growing molecules, is also a favourable target for metastasis. Bone remodelling, by OPG/RANK/RANKL pathways and by osteoclasts and osteoblasts cells, is corrupted, developing a mix of osteolytic, usually predominant, and osteoblastic elements in metastatic lesions1,2,7,20.

Many cases of soft tissues and bone craniomaxillofacial metastasis happen in patients with widespread disease, probably result of secondary spread from other metastasis, especially located in the lungs. Other proposed theories, especially in cases where the head & neck metastases is the first indication of occult malignancy, are that circulating tumour cells bypass the lung circulation through the valveless vertebral venous plexux. Furthermore, because of the tumour cells plasticity, they could spread through arteriovenous shunts1,3.

Jawbones are slightly more common affected than soft-tissues. The mandible in molar area, premolar and the angle/ramus are the most frequent localizations. Pathogenesis is not clear, but there are a haematopoietic marrow remainder located in the posterior part of the mandible in adults1,4. In relation to soft tissues, the attached gingiva and tongue are common affected sites, considering the chronic inflammation a co-factor in the attraction of metastatic cells1,20).

Main clinical differential diagnosis of metastatic lesions is with primary oral squamous cell carcinoma, benign tumours and reactive lesions such as pyogenic granuloma or gigantic epulis. They typically present as big masses with local inflammation which could infiltrate, even ulcerate skin; and they have bleeding tendency, especially of renal and hepatic origin. Occasionally, symptoms are a bit confusing such us TMJ dysfunction or numbness, known as numb chin syndrome, and the diagnosis is delayed because of deviated attention to minor stomatognathic processes. Incidental finding of asymptomatic lesions in scheduled x-ray explorations is a possibility too1,3,16,21.

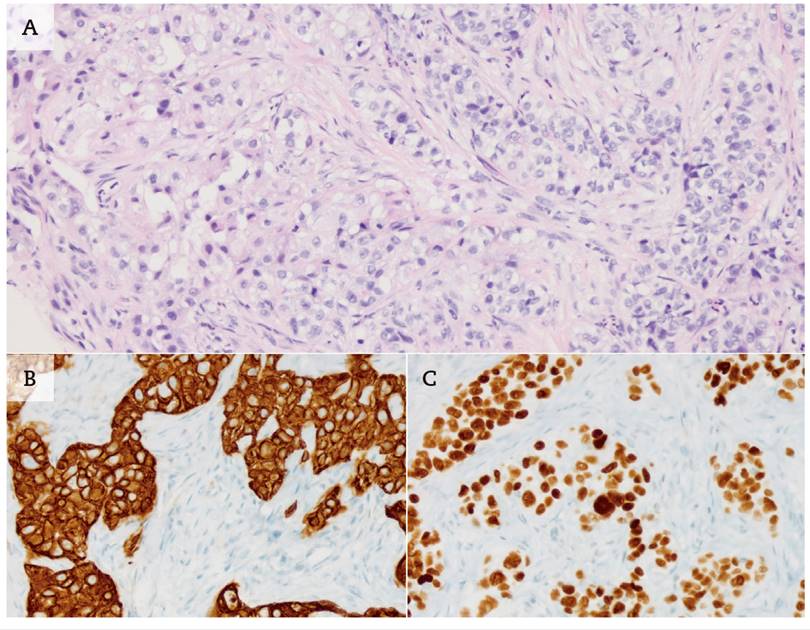

Histological malignancy morphology is not definitive of metastasis, especially complex in low differentiated salivary gland tumours. The basic inmunohistochemical (IHC) panel usually include carcinoma (keratins, p53), melanoma (S-100), sarcoma (vimentin) and lymphoma (CD45) markers (Figure 3). Even with additional IHC and molecular techniques to discern the origin, sometimes the primary site remains obscure1. Intraoral located malignant melanoma lesions are sometimes very troublesome to discern the primary site, which could even present spontaneous regression22.

Figure 3. Case 2. Lung adenocarcinoma metastasis. Fibrous connective tissue extensively infiltrated by atypical cell solid nests. Pallid eosinophilic and slightly vacuolated cytoplasm, irregular nuclei with vesiculated chromatin and prominent nucleoli. A) 200x Hematoxilin & Eosin. B) 400x CK7+. C) 400x TTF-1+.

The typical radiological appearance of metastatic lesions is a huge infiltrating, and destructive lesion, with poorly defined margins, central necrosis, and contrast enhancement (Figure 4). However, no pathognomonic image exists and any possibility is available. Bone lesion patrons tend to be osteolytic but also small osteoblastic areas could be appreciated in most of them6,23. It could be difficult to differentiate from osteonecrosis, inasmuch as a lot of patients have radiotherapy or associated drugs uptake (biphosphonates, RANKL inhibitors, VEGF inhibitors) background. This situation is more troublesome in cases without soft tissue mass. Given high suspicion and repeatedly negative biopsies, or region of difficult access such as TMJ, positron emission topographies could help to discern in favour of metastasis, as long as osteonecrosis is not in the active infection phase (Figure 5). In addition, the evolution and non-response to osteonecrosis treatment protocols will define the situation24,25.

Figure 4. Case 21. Thyroid follicular carcinoma metastasis. Solid litic expansive lesion involving the right mandible ramus and condyle. A) Pantomography. B) Computed tomography axial slice. C). Iodine-131 scintigraphy frontal view.

Figure 5. Case 14. Renal cromophobe carcinoma metastases. A-C) Fluordeoxiglucose-18 positron emission tomography. Rigth mandibule ramus periosteum inflammation, especially pronounced in the vestibular cortical, with high uptake (6.6 SUVmax). D) Computed tomography 9 months later. Progression to a mixed osteolitic and osteoblastic lesion.

Management of head & neck metastatic tumours should be multidisciplinary and individualized to each patient. Main parameters of therapy are general health condition, type and localization of the primary tumour and metastasis. Surgery, radiotherapy and systemic treatment are possible, being the palliative care the need of the hour result of the poor overall prognosis. Average survival rate in craniomaxillofacial dissemination is less than 1 year in most large case-series1,2,6,8.

CONCLUSIONS

Craniomaxillofacial metastases are usually late complications of advanced neoplasm with multiple visceral or axial skeleton lesions. In some occasions they could be the tumour debut. Most common localizations are in the mandible body and attached gingival. Most frequent strain of solid tumours is epithelial, and origin is lung, breast or liver in recent series, slightly variable depending on the geographical source and sex stratification. Multidisciplinary management could benefit the patient status and lead to more favourable outcomes, in terms of quality of life and function. There are exceptional cases of long-term survival.