INTRODUCTION

Condylar fractures account for more than a third of all mandibular fractures1. They are frequently associated to other mandibular fractures, most frequently those located in the parasymphysis and symphysis. Different classification systems have been described and used in the literature; however, they are frequently divided in: head (diacapitular) fractures, neck fractures and subcondylar fractures.

The management of condylar fractures is highly controversial and depends on the level of fracture and displacement. There are two major treatment modalities: closed treatment and open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF)2. Closed treatment is more prone to suboptimal results in determined cases, particularly deviation with mouth opening, loss of height at the mandibular rami and malocclusion, alongside with a blind immobilization of the bone segments for a prolonged time, which can have implications in the dynamics of the temporomandibular joint and the risk of arthrosis3. Nonetheless, closed treatment can also be an acceptable option in cases where no displacement nor angulation is present.

Classically, Zide and Kent's criteria for open reduction of condylar fractures have been applied4. Later, Schneider et al. settled clearer indications for ORIF in their article and recommended ORIF in fractures with an angulation higher than 10° and a shortening of more than 2 mm5. Superior functional and aesthetical results can be achieved with ORIF if correctly indicated6,7). Occlusal and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders are reduced significantly with ORIF when correctly indicated: 23 % after closed treatment vs. 9 % after surgical treatment8.

ORIF has classically been performed through different approaches: the preauricular approach, the rhitidectomy approach and the retromandibular approach. All these approaches have proven to be useful but are not exempt of risks: salivary fistula, damage to the branches of the facial nerve and visible and unesthetic scars9.

In the last decades, the endoscopic management of low condylar fractures arose as a new treatment modality with promising results, avoiding unsightly scars and lowering the risk of facial nerve damage, avoiding the most feared complications associated to ORIF. However, endoscopic repair of condylar fractures has not routinely been used: training and specific equipment are required.

In this article we retrospectively analyzed patients with subcondylar fractures treated by an endoscopic-assisted transoral approach (EA-ORIF) in our department. We describe and discuss results and complications for this group of patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

From January 2015 to January 2019 a total of 11 patients with subcondylar fractures who had been treated via EA-ORIF were consecutively selected. Preoperative CT and radiographies were taken for all patients, following our standard protocol. Both unilateral and bilateral fractures were included. Patients with associated mandibular fractures and other facial fractures were also included. Demographic data for this group was recorded. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of our Hospital (CEIm).

Patients suitable for open surgery were evaluated for endoscopic-assisted compliance. Patients who presented with fractures with more than 45° of medial deviation, fractures with more than 5 mm of overlap, high condylar fractures, patients with open fractures, patients with panfacial fractures, patients who could not undergo a long operating time and patients with a history of fracture longer than 14 days were discarded for undergoing endoscopic methods. Fractures that did not satisfy these criteria were treated via an open approach and were not included in this study.

A postoperative orthopantomography was taken on the first postoperative day and follow up was performed at 1 week postoperatively, 4 weeks, 3 months and 6 months. Follow up included an orthopantomography at 3 and 6 months to evaluate reduction and bone healing. Patients were evaluated for pain, maximum interincisal opening and the presence of deviation, TMJ clicking, lateral extrusion and malocclusion. Also, shortening of the mandibular rami was evaluated clinically and in radiographs.

Surgery was performed by the same senior surgeon, trained in endoscopic approaches and arthroscopy of the temporomandibular joint. We used a 4 mm 30° endoscope. Surgery was performed under general anesthesia and nasotracheal intubation. An intraoral incision was placed over the external oblique line in a standard fashion and an optical subperiosteal cavity was created. Then, the 30° endoscope was inserted and the fractures were inspected. Reduction was then accomplished by manipulating the teeth or distracting the mandible downwards in the angle region. Once adequately reduced the premorbid occlusion was stablished and intermaxillary fixation with screws and wires was performed. Then, fixation was performed assisted by a right-angle screwdriver/drill (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Osteosynthesis was performed using different plating methods: 2 linear 2.0 4-hole miniplates, trapezoidal plates and delta plates.

Figure 1. Once adequate reduction of the fracture is achieved, the plate is fixated using a right-angled screwdriver.

After surgery, patients were instructed in oral hygiene and a soft diet was indicated for 4 weeks. Intermaxillary fixation with elastic bands was applied for one week, and then patients initiated physiotherapy and exercises.

For all patients, number and type of plates were recorded. Results in terms of mouth opening and complications were registered and compared.

RESULTS

A total of 11 patients were included: 2 women (18.18 %) and 9 men (81.82 %). The median age for these patients was 41 years. Only 1 patient (9.09 %), patient number 5, presented with a bilateral subcondylar fracture, and EA-ORIF was decided in one of the fractures, whilst the other fracture, which was non-displaced, was treated via closed treatment with IMF and a soft diet. The remaining 10 patients (90.91 %) had unilateral fractures. The most common etiology was interpersonal violence (6 patients, 63.63 %) and traffic accidents (3 patients, 27.27 %). A total of 5 patients (45.45 %) presented with accompanying mandibular fractures, being the parasymphysis the most common location.

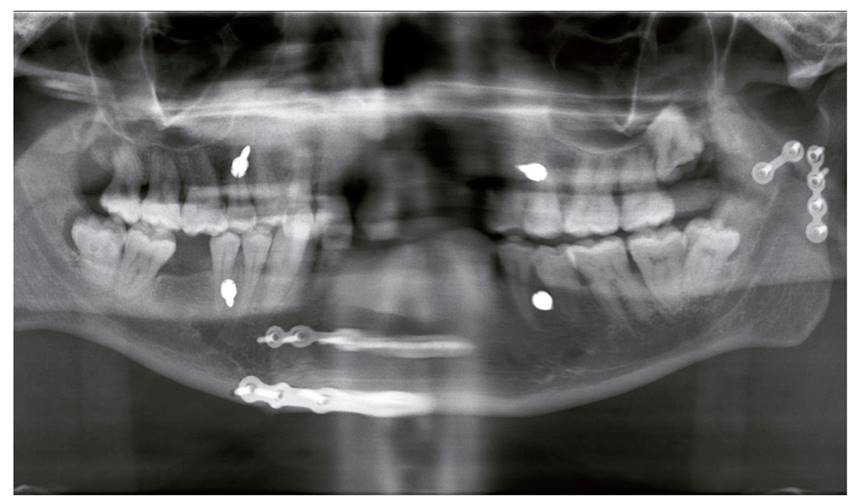

Most patients received a 2 linear plate osteosynthesis (5 patients) (Figure 3) or a delta plate (Figure 4) (4 patients). Two patients (18.18 %) received a trapezoidal plate.

Figure 3. A postoperative radiograph showing a left subcondylar fracture treated with 2 linear plates via EA-ORIF.

Complications are presented in Table 1 for all patients. One patient (9.09 %), patient number 1, suffered transient damage to the marginal and frontal branches of the facial nerve, which resolved uneventfully within 6 months. No cases of salivary fistula or sialocele were found in this study. Also, no complications related to the surgical wound or scarring were found.

Regarding hardware complications, two of these patients, patients number 3 and 6, (18.18 %) had their plates removed. The first patient, patient number 3, was treated with a trapezoidal plate and had it removed one month postoperatively due to infection at the fracture site. The patient required antibiotic treatment for 1 week (amoxiciline-clavulanic acid 875/125 mg) and the plate was removed. The patient was treated conservatively with a soft diet. The second patient with hardware complications, patient number 6, had been treated with 2 linear 2.0 mm plates and both were removed one year later due to complaints and pain at the surgical site. Nonetheless, no signs of infection or pseudoarthrosis were observed. He did not show misalignment on postoperative radiographs and neither did he refer malocclusion or TMJ symptoms. The remaining nine patients had no complications associated to the hardware.

Mean mouth opening at one week postoperatively was 31.8 mm with a standard deviation (SD) of 2.75. At three months postoperatively, it increased to 35.6 mm with a SD of 1.50. At the 6-month follow-up, the mean mouth opening was 37.8 with a SD of 1.12 (Figure 5). This meant an increase of 18,86 % at the longest follow-up.

Figure 5. Mouth opening at 1 week postoperatively, 3 months postoperatively and 6 months postoperatively.

Mild deviation with mouth opening was noted in all patients at the end of first postoperative week. This is a common finding during the first days after surgical treatment of subcondylar fractures. By 3 months postoperatively, only two patients (18,18 %), patients 8 and 11, presented with persistent deviation with mouth opening that persisted at the longest follow-up. No TMJ symptoms were reported for these patients regarding clicking and blocking. All patients received intermaxillary fixation (IMF) and elastics for one week postoperatively. Only one patient (9,09 %), patient 10, reported malocclusion after this period and was treated with further IMF for 3 weeks. None of the 11 patients had the endoscopic approach converted to open surgery. No intraoperative complications were reported either.

DISCUSSION

The treatment of condylar fractures has been an arduous topic of debate and has significantly changed in the last century. They can be managed both via conservative treatment or by open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF)10,11. Traditionally, the majority of condylar process fractures have been managed with closed techniques, typically with maxillomandibular fixation and elastics12. However, no anatomical reduction can be accomplished, and worse functional and aesthetic results were described and soon ORIF became the gold standard technique in cases of angulation or displacement. Restoring the adequate anatomy of the condyle and enabling immediate normal function are the main advantages of the ORIF approach13.

So far there is a lack of consensus and an endless debate regarding the management of subcondylar fractures13. In general, absolute indications for ORIF of condylar fractures include displacement into the middle cranial fossa, failure to obtain dental occlusion via closed reduction, lateral extracapsular displacement of the condyle, presence of a foreign body, or an open fracture with potential for fibrosis 14.

Different surgical approaches exist for ORIF15, however they carry a risk of facial nerve damage, salivary fistula, sialocele, scarring, etc. Later, the intraoral approach for subcondylar fractures was described, with the aim to avoid the aforementioned complications associated to ORIF. The first case series of condylar fractures managed via an intraoral approach were reported by Lee et al. in 199816,17, who used this approach assisted by a transbucal trocar. Schon18 stated that intraoral approaches are better suited for condylar fractures with lateral over-ride and undisplaced or minimally displaced fractures.

In 1998, Jacobovicz19 et al. described the endoscopic assisted approach to condylar fractures with the aim to reduce complications and combine the best of both closed and open treatment8,20. The current literature states that with this approach, risk of facial nerve injury is significantly reduced as well as scarring, since this procedure is performed through an intraoral incision, showing advantages over both open and closed treatments. However, it is technically demanding and requires training and specific equipment. It should not be indicated in all condylar fractures and shall not be considered in cases with medial override, high condylar neck fractures and large angulation, panfacial fractures and open fractures. Also, some authors report worse reduction of the fracture due to the difficulties in handling and the reduced surgical field, with higher rates of hardware failure and nonunion.

Lee et al. reported a large series of subcondylar fractures treated via endoscopic-assisted approach, treating a total of 22 fractures with overall good functional and aesthetic results16. Later17, they would report their experience with 40 fractures treated endoscopically. In this latter article, they reported one case of transient facial paralysis and 3 cases of hardware fracture, with a median maximum mouth opening of 43 mm at 8 weeks postoperatively, reporting good occlusion and good alignment. Nogami et al.21) studied 30 patients treated either via an extraoral retromandibular approach or an intraoral endoscopic approach using right-angled instruments. In the ORIF group, 7 patients had transient facial paralysis, while no cases of facial paralysis were found in the EA ORIF group. TMJ symptoms were similar for both groups, however, median mouth opening 1 month postoperatively was higher in the open approach compared to the endoscopic approach (35.7 mm vs. 28.4 mm), with comparable results at 6 months postoperatively.

Creo et al.3) reported their experience in the endoscopic-assisted management of condylar fractures in 26 patients. They reported adequate alignment in 80.8 % of fractures, with a mean maximum interincisal opening (MIO) of 35 mm at 4 weeks postoperatively. In our study, we did not report MIO at one month, but at 3 months it was 35.6 mm. They found good occlusion and no cases of mandibular height loss nor open bite, similarly to our results. However, they found no cases of facial paralysis or hardware failure were described in their article. In our study we found one case of transient facial nerve damage (9.09 %) and two cases of hardware removal (18.18 %). They described one case with persistent lateral deviation and one case of surgical site infection that required drainage, but the hardware was not removed. In our study we found two patients with persistent lateral deviation at 3 months postoperatively (18.18 %). They concluded that the intraoral endoscopic-assisted approach in condylar fractures is a safe, reproducible and efficient technique in most extracapsular fractures and insist on including this technique in the armamentarium of the maxillofacial surgeon.

Frenkel et al.13 also analyzed their results in the treatment of condylar fractures via an endoscopic-assisted approach in 12 patients. Mean time for EA-ORIF in their report was 180 minutes, achieving stable occlusion in all patients and a significant improvement in maximum mouth opening (45 mm) 6 months postoperatively.

Goizueta et al.9) reported their experience in 53 patients (55 fractures) treated of condylar fractures via EA-ORIF. Mean surgical time was 184.5 min (85-465), quite similar to that of Frenkel et al 13. They found overall satisfactory radiological reduction in 92 % of the fractures, similar to our results (90.9 %). A total of ten patients presented with intraoperative or postoperative complications (18.8 %). Three patients presented with temporal paralysis of the frontal branch (5.6 %), two patients required myorelaxant treatment and five patients required occlusal adjustments. Four patients (7.5 %) were reoperated.

Existing literature on EA-ORIF of subcondylar fractures suggest that this modality has comparable functional results in terms of MIO and masticatory and joint function. Furthermore, the risk of complications such as facial nerve damage, salivary gland fistula, sialocele and unsightly scars are significantly reduced. Despite, the main drawbacks of EA-ORIF include its steep learning curve and the need for special equipment and training. Another alleged drawback of this technique is the extended operating time, which has been reported to decrease with surgeon's experience. Frenkel13 et al. found a significant decrease in operating time after the 5th operation.

In our study, most patients received a 2 linear plate osteosynthesis 45.45 % and 36.36 % received a delta plate. Both types of osteosynthesis are acceptable in the treatment of subcondylar fractures. Generally, we would decide between one or another depending on the space available for plate placement and the fracture line: if difficulties are found for the placement of two plates, then a 3D type of plate such as the delta plate would be preferred. This is one of the main disadvantages of EA-ORIF, since many surgeons would feel reluctant to this approach due to the limited surgical and visual field, as well as the difficulties in handling the instruments and positioning the plates and screws.

We found two cases (18.18 %) where the plates were removed. This is an elevated percentage and a comparative study between ORIF and EA-ORIF regarding hardware removal rates would be interesting. A possible explanation is that the approach for EA-ORIF was performed via an intraoral approach, and this may lead to higher rates of infection and contamination of the plate. However, it should be considered that the number of patients is limited, and a broader series is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Mild deviation with mouth opening was noted in all patients at the end of first postoperative week. This is a common finding in the first days after treatment of subcondylar fractures. By 3 months postoperatively 18.18 % of patients presented with persistent deviation with mouth opening that persisted at the longest follow-up, which is a reported complication in subcondylar fractures. However, these patients were satisfied with the results and this deviation did not interfere with jaw function. On the other hand, no TMJ symptoms such as clicking, or blocking were reported by these patients at the longest follow up. We believe that physiotherapy and early jaw exercises are of utmost importance to avoid future TMJ problems in these patients. Only one patient presented with malocclusion that required IMF for a longer period of time, with good results. No signs of malocclusion were found for the rest of patients.

We found 1 case of transient facial paralysis in our study group (9.09 %) which resolved satisfactorily within 6 months. This complication has been reported by other authors9,17 and it is believed that is provoked by the distension of tissues created in the optical cavity for handling and manipulation of instruments. No cases of salivary fistula or sialocele were found in this study, similarly to previous publications3,9,21. Also, no complications related to the surgical wound or scarring were found.

We report similar MIO improvement to previous authors3,21, being 31.8 mm at one week after surgery and increasing to 35.6 mm by 3 months and 37.8 by 6 moths postoperatively with a mean increase of 18.86 % at the longest follow-up.

Regarding limitations to this study, the number of patients is small and limited and could be increased, so these results should be considered cautiously. The main drawback of EA-ORIF is the difficulty that resides in the technique and surgical field, which is limited. Therefore, we think that for future publications, mean surgery time should be recorded and analyzed, similar to other publications 9,1.

Also, this study lacks control group, and therefore a proper comparison to ORIF could not be made. We believe that a prospective comparative study with an open approach (ORIF) cohort could be interesting in order to compare functional outcomes and complications for both groups as well as total operative time for further conclusions.

CONCLUSION

Transient damage to the facial nerve is diminished but not completely avoided with EA-ORIF, as we found one patient who presented with transient damage to the facial nerve. We report no complications related to the parotid gland or scarring were found. Also, we found two cases of hardware removal (18.18 % of patients). We believe further studies to compare this rate and other complications to the ORIF approach are needed. For the rest of patients, no hardware complications or signs of malocclusion were found. No TMJ complications were reported as well at the longest follow-up.

EA-ORIF is a safe and acceptable alternative to ORIF in subcondylar fractures. However, adequate equipment and intensive training is required for proper management and optimal results, as well as proper patient selection.