Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Neurocirugía

versión impresa ISSN 1130-1473

Neurocirugía vol.20 no.1 feb. 2009

Hemorrhagic stroke with intraventricular extension in the setting of acute posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES): case report

Infarto hemorrágico con extensión intraventricular en el contexto de leucoencefalopatía aguda posterior reversible (LPR): descripción de un caso

J. Gasco*; L. Rangel-Castilla*; S. Clark**; B. Franklin; L. Satchithanandam*** and P. Salinas*

*Division of Neurological Surgery at University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas.

**Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine at Universityof Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas.

***Department of Radiology at University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas.

SUMMARY

We report the case of an eighteen year-old pregnant female with preeclampsia and florid signs and symptoms of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) in whom intracerebral hemorrhage was evidenced following delivery. Management included blood pressure control, external ventricular drainage and lumboperitoneal shunt. To our knowledge this is the first report of intracranial hemorrhage occurring concurrently with peripartum acute PRES. This case was successfully treated with good outcome upon conclusion of management, thus making awareness of this potentially fatal complication and its suggested management for successful outcome necessary for neurosurgeons, neurologists and intensivists alike.

Key words: Preeclampsia. PRES. Reversible encephalopathy. Intracranial hemorrhage. Intraventricular hemorrhage. External ventriculostomy drainage.

RESUMEN

Describimos el caso de una mujer embarazada de 18 años con preeclampsia y signos y síntomas floridos de leucoencefalopatía posterior reversible (LPR) en la que se evidenció la presencia de hemorragia cerebral tras el parto. El tratamiento de la enferma incluyó el control de la presión arterial, la utilización de drenaje ventricular externo y la colocación de una válvula lumboperitoneal. En nuestro conocimiento esta es la primera descripción en la literatura de la concurrencia de hemorragia intracraneal con la LPR. Este caso fue satisfactoriamente tratado con un buen resultado, haciendo que la sospecha y el conocimiento de esta posible fatal complicación y su correcto tratamiento sea importante para neurocirujanos, neurólogos e intensivistas.

Palabras clave: Preeclampsia. LPR. Encefalopatía reversible. Hemorragia intracraneal. Hemorragia intraventricular. Drenaje ventricular externo.

Introduction

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) describes a constellation of multiple clinico-radiological findings. The clinical spectrum includes typically headaches, seizures, altered mental status and visual complaints. PRES was first described in 1996 by Hinchey et at.7. In this landmark paper, 15 patients were described to have a reversible syndrome characterized by headache, altered mental status, seizures, and loss of vision associated with imaging findings compatible with predominantly posterior white matter disease (leukoencephalopathy).

The accompanying radiological findings, necessary for diagnosis, include areas of vasogenic edema predominantly in parietooccipital areas but other lobes5, deep white matter and infratentorial structures6 can be affected. In a case series of 76 patients recently reported by McKinney et al.9, the primary region of involvement was parietooccipital (98.7%), followed by posterior frontal (78.9%), temporal (68.4%) thalamus (30.3%), cerebellum (34.2%) brainstem (18.4%) and basal ganglia (11.8%).

Preeclampsia and eclampsia are well known causative factors of PRES and its associated neurological manifestations2, however, the presence of hemorrhagic events in the setting of PRES has been remotely described8,12.

We discuss a case of an 18-year-old pregnant female with preeclampsia who developed an intracerebral hemorrhage with intraventricular extension. Management required neurosurgical intervention including temporary external ventricular drainage and lumboperitoneal shunt. The association of preeclampsia, intracerebral hemorrhage and PRES is discussed and pertinent literature is reviewed.

Case report

An 18 year-old Hispanic female, G1P0 at 38 weeks and 2 days estimated gestational age by bedside sonogram, presented to the emergency room with a 24-hour history of progressively intense headaches followed by emesis decreased level of consciousness, visual ataxia and visual inattention. The patient had no prenatal care and had denied the pregnancy.

Her blood pressure values ranged 140-160/90-100 mmHg. Proteinuria was evidenced on catheterized specimen (300 mg/dL). Pertinent laboratory values were as follows: serum sodium 140 mmol/l (normal), potassium 3.3 mmol/l (low), creatinine 0.94 mg/dl (elevated for term pregnancy) and serum calcium 8.6 mg/dl (low-normal). Prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and platelet count were within normal limits.

The patient was transferred to the labor and delivery unit with a working diagnosis of preeclampsia and probable PRES, and received a 4 g intravenous loading dose of magnesium sulfate. The initial fetal heart tracing was non-reassuring with presence of variable decelerations In addition, the patient's cervical exam was 1 cm dilation with 50% effacement, thus making induction of labor unfavorable and decision was made to proceed with urgent cesarean section under spinal block with bupivacaine. After an uncomplicated and expeditious delivery the patient was transported for urgent neuroimaging.

At that time, the patient remained somnolent but was arousable, conversant, and able to follow commands. A non-contrasted computerized tomography (CT) of the head revealed an intraparenchymal hemorrhage measuring 3.8 x2.2 cm located at the level of the left caudate nucleus with intraventricular extension and 5 mm left-to-right midline shift. (Figure 1-A).

Figure 1-A. CT Head without contrast: hemorrhage in the left caudate

lobe along with intraventricular hemorrhage, surrounding edema,

and hydrocephalus. Occipital lobe hypodensities in the cortical/subcortical white matter are observed.

The neurosurgery service team was then consulted. At the time of neurosurgery evaluation, the patient's blood pressure was 200/100 mmHg. Glasgow coma score (GCS) was 8 E2V1M5. The patient's pupils were equally reactive (4 mm to 3 mm) with left gaze preference and right sided neglect. Patient was obtunded, only able to unilaterally localize to painful stimuli with the left arm. The decision to intubate and perform emergent ventriculostomy placement was made and a bedside right frontal catheter system (Codman, Raynham, MA) was placed in standard sterile conditions to a depth of 6 cm obtaining serosanguinous cerebrospinal fluid. Initial intracranial pressure was 8 mmHg. The draining system was placed at 0 cmH20 over the external auditory meatus obtaining 5-10 cc of CSF per hour (Figure 1-B).

Figure 1-B. CT Head without contrast (post-ventriculostomy): a new right

frontal ventriculostomy catheter traverses the right lateral ventricle.

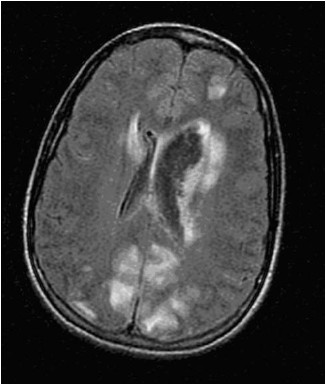

The patient remained intubated and under propofol infusion with hourly assessments. Four hours post-procedure, cognitive, vision, and motor functions were noted to be restored and separation from the ventilator was successful. A brain MRI was performed 12 hours after initial presentation showing increased T2/FLAIR signal in the pons, right cerebellar hemisphere, left thalamus and bilateral involvement of occipital and frontal lobes and deep white matter. MRA of the neck and brain showed no abnormalities. (Figure 2-A).

Figure 2-A. MRI brain axial FLAIR image (9002/2200/ 132)-increased foci of high signal

intensity affects the cortex and subcortical white matter of both occipital

lobes and to a lesser extent the left frontal lobe.

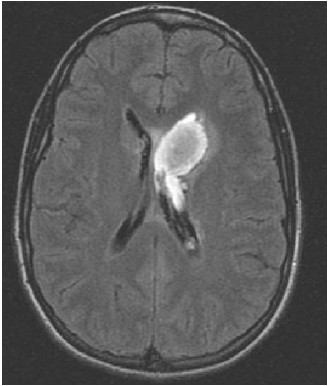

Initial blood pressure management included continuous nicardipine infusion titrated to obtain a MAP between 60 and 100mmHg. This was successfully transitioned to oral enalapril (20mg daily) and amlodipine (10mg daily) after 24 hours. In addition, the patient remained on magnesium sulfate for seizure prophylaxis from the time of initial presentation until 24 hours postpartum. The ventriculostomy catheter was removed four days after placement. Follow-up imaging 11 days after presentation revealed significant resolution of most lesions (Figure 2-B).

Figure 2-B: MRI brain-axial FLAIR image. (9002/2200/ 125): hospital day 12. Previously

seen foci of high signal intensity in the cortical/subcortical white matter of the occipital lobes are now resolved.

Of uncertain physiopathological significance, increased T2WI signal within the central pons and splenium of the corpus callosum were also noted. Both areas had previously exhibited increased signal intensity.

Due to persistent symptomatic headaches, two high-volume lumbar punctures were performed on postpartum days 8 and 11. Opening pressures were 43 and 41 cmH2O, draining 45 and 50cc respectively. Due to the presence of high cerebrospinal fluid pressure measurements, the decision to proceed with elective shunting procedure was made. The absence of increased ventricular size led us to choose a lumboperitoneal shunt system (Integra Heyer-Schulte, Plainsboro, NJ). The procedure was carried without complications and the patient was discharged home on postpartum day 13.

Discussion

The nature of hemorrhagic events in the setting of PRES and preeclampsia/eclampsia is unclear. Encephalopathy changes are thought to be related to cerebral dysautorregulation and increased cerebrovascular resistance. Oehm et al10, in a study with four patients with preeeclampsia and PRES found severe impairment of cerebral dynamic autoregulation by measurement of the resistance index with transcranial Doppler measurements. Previous reports showed no impairment of autoregulatory index measured by transcranial Doppler11 but the preeclampsia group studied was asymptomatic. Belfort et al. in a prospective observational perfusion-based study, concluded that high cerebral perfusion pressure is more common in women with severe preeclampsia than in women with mild preeclampsia1. It could be inferred that when symptoms occur in preeclampsia, the autoregulatory compensation mechanisms are impaired. It has been postulated that the lesser presence of sympathetic supply to the posterior circulation could be responsible for an increased susceptibility to losing autoregulatory compensation mechanisms, explaining the predominance of lesions in the occipital region3,4. Changes in the blood brain barrier as a consequence of dysautorregulation could therefore be responsible for the encephalopathy produced initially, and this disruption could potentially create a vulnerability and predisposition of the microcirculation to a hemorrhagic event.

The association of acute PRES and intracranial hemorrhage occurring simultaneously and requiring neurosurgical intervention to our knowledge has not been described. Only one previous report relating PRES and intracranial hemorrhage requiring neurosurgical intervention was identified in our literature search, but the hemorrhagic event was delayed after the initial onset of PRES for approximately two months. Other confounding factors such as heparin use and dyalisis for acute renal failure where equally involved8.

The patient reported, a 16 year-old male with chronic renal failure, developed acute PRES during a hypertensive crisis and two months following regression of the acute PRES-related symptoms, the patient developed a posterior fossa intracranial hemorrhage. Other factors such as the fact that the patient had been started in low-molecular weight heparin two weeks prior or was subject to hemodialysis, may have contributed to the hemorrhagic event. In this case the outcome was poor, and the patient unfortunately succumbed to the insult despite surgical evacuation of the hemorrhage. Some differences are therefore evidenced with our report. First, both the intracranial hemorrhage and PRES-related symptoms occurred within hours. Second, the location of the hemorrhage, in our case being supratentorial (left caudate nucleus), differs from the described cerebellar hemorrhage and adds more awareness to the potential influence of PRES in areas that are not supplied by the posterior circulation. Third, no drugs were identified in our screening and the patient did not receive heparin or was subject to hemodialysis. This in our opinion represents a true potential predisposition of patients with PRES to have hemorrhagic events with no other confounding factors.

We believe that our favorable outcome was influenced by rapid delivery, blood pressure control and immediate ventriculostomy placement once the intraventricular hemorrhage was identified. The significant headaches suffered by the patient along with high cerebrospinal fluid pressures, justified the decision to place a lumboperitoneal shunt to prevent symptomatic communicating hydrocephalus in the future. Three month follow up confirmed resolution of headaches completely.

In conclusion, PRES and its associated symptoms should be regarded as a potential cause of devastating neurological injury. Awareness for neurosurgeons and neurologist that acute hemorrhagic events requiring intervention may occur in the setting of acute PRES-related symptoms irrespective of the triggering factors, is of paramount importance. In such situation, prompt neurosurgical consultation and neuroimaging with computerized tomography is warranted. MRI should be performed once the patient's condition is stabilized.

References

1. Belfort, M.A., Grunewald, C., Saade, G.R., Varner, M., Nisell, H.: Preeclampsia may cause both overperfusion and underperfusion of the brain: a cerebral perfusion based model. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1999; 78: 586-591. [ Links ]

2. Belogolovkin, V., Levine, S.R., Fields, M.C., Stone, J.L.: Postpartum eclampsia complicated by reversible cerebral herniation. Obstet Gynecol 2006; 107: 442-445. [ Links ]

3. Casey, S.O., McKinney, A., Teksam, M., Liu, H., Truwit, C.L.: CT perfusion imaging in the management of posterior reversible encephalopathy. Neuroradiology 2004; 46: 272-276. [ Links ]

4. Chou. M.C., Lai, P.H., Yeh, L.R., et al.: Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: magnetic resonance imaging and diffusion-weighted imaging in 12 cases. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2004; 20: 381-388. [ Links ]

5. Covarrubias, D.J., Luetmer, P.H., Campeau, N.G.: Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: prognostic utility of quantitative diffusion-weighted MR images. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2002; 23: 1038-1048. [ Links ]

6. Hagemann, G., Ugur, T., Witte, O.W., Fitzek, C.: Recurrent posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES). J Hum Hypertens 2004; 18: 287-289. [ Links ]

7. Hinchey, J., Chaves, C., Appignani, B., Breen, J., Pao, L., Wang, A.: A reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome. N Engl J Med 1996; 334: 494-500. [ Links ]

8. Machinis, T.G., Fountas, K.N., Dimopoulos, V.G., Troup, E.C.: Spontaneous posterior fossa hemorrhage associated with low-molecular weight heparin in an adolescent recently diagnosed with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: case report and review of the literature. Childs Nerv Syst 2006; 22: 1487-1491. [ Links ]

9. McKinney, A.M., Short, J., Truwit, C.L., et al.: Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: incidence of atypical regions of involvement and imaging findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2007; 189: 904-912. [ Links ]

10. Oehm, E., Hetzel, A., Els, T., Berlis, A, et al.: Cerebral hemodynamics and autoregulation in reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome caused by pre-eclampsia. Cerebrovasc Dis 2006; 22: 204-208. [ Links ]

11. Sherman, R.W., Bowie, R.A., Henfrey, M.M., Mahajan, R.P., Bogod, D.: Cerebral haemodynamics in pregnancy and pre-eclampsia as assessed by transcranial Doppler ultrasonography. Br J Anaesth 2002; 89: 687-692. [ Links ]

12. Wartenberg, K.E., Parra, A.: CT and CT-perfusion findings of reversible leukoencephalopathy during triple-H therapy for symptomatic subarachnoid hemorrhage-related vasospasm. J Neuroimaging 2006; 16: 170-175. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Jaime Gasco,

MD. University of Texas Medical Branch.

Division of Neurological Surgery.

301 University Boulevard. Galveston, Texas 77555- 0517.

Recibido: 8-02-08.

Aceptado: 1-04-08