PYD Interventions: Targeting Identity Formation Processes

Initial evidence of the effectiveness of positive youth development (PYD) programs in promoting positive change in concepts and constructs related to positive identity has led to an interest in developing, implementing, and evaluating interventions that specifically target core components of identity formation in adolescents as a strategy for promoting positive outcomes and preventing negative outcomes. The potential utility of interventions that target identity formation has also been discussed extensively within the identity literature (Archer, 1994; Erikson & Erikson, 1957; Hernandez, Montgomery, & Kurtines, 2006; Kurtines et al., 2008; Montgomery, Hernandez, & Ferrer-Wreder, 2008; Montgomery et al., 2008).

As Ferrer-Wreder, Montgomery, and Lorente (2003) point out, the literature on identity formation has a potential contribution to make to efforts to promote positive development and prevent problematic outcomes, in part because it offers guidance for the effort to identify and investigate the component processes of identity formation. Montgomery et al. (2008) suggest that the inclusion of variables tapping key identity processes and outcomes, such as identity cohesion, style, distress, and turning points, in psychosocial intervention research would make these interventions for youth more effective and potent, in part because this type of research would add to knowledge about for whom interventions work and why they work.

Within the identity literature, two core identity processes have been discussed extensively: identity exploration and identity commitment (Marcia, 1966, 1980, 1988). Elaborating upon Erikson’s writing, Marcia (1966) described behavioral markers of the processes by which an adolescent consolidates a coherent sense of identity. Adolescents face the challenge of first exploring multiple possible identity alternatives in order to make decisions about life choices and then choosing one or more of the multiple possible identity alternatives and following through with them (Grotevant, 1987; Marcia, 1980, 1988; Schwartz, 2001). According to this formulation, identity exploration is the search for a revised and updated sense of self, and identity commitment is the adherence to a particular course of action characterized by a self-selected specific set of goals, values, and beliefs (Marcia, 1988; Schwartz, 2001).

As Bosma and Kunnen (2001) point out, a number of theoretical perspectives on identity development (e.g., Adams & Marshall, 1996; Breakwell, 1988; Grotevant, 1987; Kerpelman, Pittman, & Lamke, 1997; Kroger, 1997) have sought to extend and refine Marcia’s (1966) conceptualization of identity commitment and identity exploration by emphasizing the transaction between the individual and the environment. According to Bosma and Kunnen (2001), conflict or mismatch between existing identity commitments and information from an individual’s environment represents the “starting point” for the identity process, a conceptualization that is consistent with the view of adolescence as a developmental period with immense personal and contextual change, including biological, cognitive, and social changes. Whereas the conflict between existing identity commitments and the environment has been described as the “starting point” for the identity process (Bosma & Kunnen, 2001), identity exploration has been described as the “work” of the identity process (Grotevant, 1987) and includes both cognitively focused and emotion focused components (Schwartz, 2002; Soenens, Berzonsky, Vansteenskiste, Beyers, & Goosens, 2005). Marcia’s conceptualization of identity exploration maps directly onto Erikson’s description of the identity crisis, and the terms are usually used interchangeably (Adams et al., 2001; Kidwell, Dunham, Bacho, Pastorino, & Portes, 1995; Waterman, 1999).

Self-Construction and Self-Discovery in Adolescence

According to Erikson (1963), the ascendant psychosocial task of adolescence is the integration of the roles, skills, and identifications youth have learned in childhood with the expectations of the adult world into a coherent sense of identity. The search for this sense of identity is characterized by the crisis between the ego syntonic tendency toward identity synthesis, a self-constructed dynamic organization of drives, abilities, beliefs, and individual history, and the ego dystonic tendency toward identity confusion, the lack of such an organization. Crisis is thought to be prompted by either an identity deficit, in which the adolescent encounters circumstances in which he or she lacks enough of a sense of identity to make important life decisions, or an identity conflict, in which the adolescent experiences circumstances that bring to light the incompatibility of two or more aspects of his or her identity. Both syntonic and dystonic elements are necessary in the positive development of the adolescent as the dialectic tension between them represents a time of increased vulnerability and potential for development (Erikson, 1968, 1985). As such, the identity crisis, also known as identity exploration (Adams et al., 2001; Waterman, 1999), is considered a normal and healthy developmental challenge during adolescence that involves processes necessary for finding, assessing, and establishing identity commitments.

Self-Construction: The Identity Style Model

Within the identity exploration literature, a significant body of work has drawn upon the constructivist tradition in asserting that the individual is an intentional agent who participates in the construction of his or her world. The individual is depicted in the role of a scientist, proactively making identity-related choices by forming and testing hypotheses in a cognitive, rational, and dispassionate manner (Berman, Schwartz, Kurtines, & Berman, 2001; Berzonsky, 1989; Grotevant, 1987). Identity theories in this vein have emphasized abilities and orientations (Grotevant, 1987), cognitive problem-solving competence (Berman et al., 2001), and cognitive processing styles (Berzonsky, 1989).

Berzonsky’s (1989) constructivist approach to identity formation emphasizes the cognitive processing orientations with which a person forms and maintains an identity. Drawing on the work of Kelly (1955), Berzonsky (1993) proposed that people are self-theorists in that they create a conceptual structure that helps them make sense of their experience. There are three types of self-theorists: (1) the scientific information-oriented, (2) the dogmatic normative-oriented, and (3) the ad hoc diffuse/avoidant-oriented. When applied to the psychosocial task of identity formation, these orientations toward self-construction are termed identity styles. The informational orientation is characterized by the seeking out and utilizing of self-relevant information when making decisions related to identity (Berzonsky, 1993), while the normative orientation is characterized by conformation to the expectations of others or of reference groups. The diffuse avoidant identity style is often distinguished by avoidance of identity-related problems.

Most individuals have the ability to use all three identity orientations by late adolescence (Berzonsky, 1990). Though not necessarily more advanced than normative style, the informational style has been associated with several indices of positive psychosocial adjustment in adolescence, including: openness to ideas and experience and the need to exert cognitive effort (Berzonsky, 1990); active, problem-focused coping strategies and social support seeking (Berzonsky & Sullivan, 1992); and self-reflective tendencies, salience of personal identity content, and openness to feelings and fantasies (Berzonsky & Sullivan, 1992). Adolescents who score higher on measures of informational style tend to come from authoritative homes (Berzonsky, 2004), have well-defined educational plans, and have high levels of both conscientiousness and goal-directedness (Berzonsky & Kuk, 2000). Though evidence suggests that while both normative and informational styles are generally more adaptive than diffuse avoidant style, the informational style is more adaptive than the normative style in situations in which youths must assume personal responsibility for academic priorities and monitor their own activities and progress (Berzonsky & Kuk, 2000).

Self-Discovery: Feelings of Personal Expressiveness

Within the identity literature, a body of work is emerging in the humanist tradition, resonant with the rapidly growing interest in positive psychology (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000), to emphasize the consideration of personal strengths and creative potentials. The individual is depicted as becoming or growing toward the fulfillment of his or her potential. Theories in this vein have asserted the importance of self-actualization (Maslow, 1968), flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990), and feelings of personal expressiveness (Waterman, 1990). Flow is an affective state characterized by a balance between the challenge at hand and the skills one brings to it (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990), while self-actualization refers to fulfilling one’s potentials and living up to one’s ideals on a consistent basis (Maslow, 1968). Personal expressiveness emphasizes the subjective experience associated with engaging in identity-related activities (Waterman, 2005) and the self-discovery process (Waterman, 1984).

Personal expressiveness is considered the second of these successively more integrated levels of affective processing, more integrated than the experience of flow and less integrated than self-actualization (Schwartz, 2002, 2006; Waterman, 1990). Feelings of personal expressiveness are defined as the positive, subjective state characterized by the deep satisfaction that accompanies engagement in activities or goals that utilize one’s unique potentials and that are hypothesized to represent one’s basic purpose in living (Waterman, 1993). While performing activities that evoke feelings of personal expressiveness, individuals experience (a) an unusually intense involvement, (b) a special fit or meshing with the activities, (c) a feeling of intensely being alive, (d) a feeling of completeness or fulfillment, (e) an impression that this is what one was meant to do, and (f) a feeling that this is who one really is (Waterman, 2005).

Existing research suggests that feelings of personal expressiveness are associated with many positive life outcomes (Csikszentmihalyi, 1975, 1990; Waterman, 1993, 2004). Participation in personally expressive activities is related to higher levels of intrinsic motivation to accomplish life tasks (Waterman, 2005), as well as higher scores on measures of perceived competence and self-realization values and importance. Evidence suggests a strong association between personal expressiveness and self-determination (Waterman et al., 2003). Recent studies conducted with high school students have also found evidence of the association between personal expressiveness and several indices of positive psychosocial adjustment in adolescence. Feelings of personal expressiveness, in combination with flow and goal-directed behavior, have been found to be significantly associated with higher levels of adolescent-reported psychological well-being and lower levels of adolescent reported problem behavior (Palen & Coatsworth, 2007). While there appear to be gender differences in the types of activities that males and females find personally expressive (socializing, instrumental, and literary activities for females and sports/physical activities for males), reported levels of personal expressiveness within those activities have been found to be similar across gender (Sharp, Coatsworth, Darling, Cumsille, & Ranieri, 2007). Research also suggests that there are more similarities in feelings of personal expressiveness across countries and cultures than differences (Coatsworth et al., 2005; Sharp et al., 2007).

Self-Construction and Self-Discovery in Positive Youth Development

Because adolescents must begin to choose and commit to the goals, roles, and beliefs about the world that give life direction and purpose as well as coherence and integration (Erikson, 1968), models of identity development that integrate the self-construction and self-discovery processes underlying identity exploration may be of particular utility in psychosocial interventions, such as the PYD, that focus on self-construction and self-discovery among adolescents. Previous positive youth development research has recognized the potential of models integrating self-construction and self-discovery processes to guide the development, implementation, and evaluation of psychosocial developmental interventions with adolescents exposed to risks associated with living in low-income urban community contexts (Albrecht, 2007).

Evaluating the Formation of a Self-Structure: Relational Data Analysis of Life Goals

It is important to note that the construction of this self-structure has many measureable dimensions (e.g., identity exploration and commitment, identity style), any of which may potentially be measured and evaluated with quantitative strategies for analyzing linear, additive change. However, a strictly quantitative approach cannot capture changes in the meaning and significance of critical experiential components of an individual’s sense of self and identity because these changes are subjective in nature and characterized by an increasingly complex (i.e., integrated) structural organization with emergent new properties. A quantitative approach is not capable of the detection of qualitative change that involves the emergence of new content domains or new structural organizations outside empirically or theoretically pre-selected content domains because fixed response quantitative measures are by design not capable of collecting and capturing data outside of their pre-specified content domains. On the other hand, as discussed previously, free-response qualitative measures are capable of capturing the emergence of new content domains or new structural organizations.

While previous studies have evaluated the effect of the CLP intervention on change in identity processes (e.g., Albrecht, 2007; Eichas et al., 2010) or change in subjective sense of self and identity through the examination of narrative expressions of meaning and significance (e.g., Arango, Kurtines, Montgomery, & Ritchie, 2008; Kortsch, Kurtines, & Montgomery, 2008), and intervention change in identity processes as mediators of intervention change in sense of self and identity and sense of self and identity (Eichas et al., 2010), no studies, to date, have incorporated both quantitative measures of identity processes and multiple qualitative assessments of subjective sense of self and identity. The current study sought to contribute to the evaluation of Eichas et al., (2010) outcome mediation model (OMC) and, toward that end, had two main research aims.

The first aim of this study was to investigate CLP intervention effectiveness in promoting positive change in self-constructive and self-discovery identity exploration processes and level of identity resolution in a psychosocial intervention and effects on behavioral outcomes. The second aim was to investigate examined intervention change in identity processes as mediators of intervention change in subjective (qualitative) sense of self and identity.

This study furthered the evaluation of the OMC by identifying which core identity processes (i.e., cognitive identity exploration, identity commitment, and emotion focused identity evaluation) serve as mediators of effects of participation in the CLP on change in sense of self and identity and behavioral outcomes.

Conceptual and Theoretical Analyses: Identification of Properties

The short-term outcome study reported here was conducted as part of the evaluation of the Changing Lives Program (CLP) participatory transformative intervention approach in promoting both positive change in sense of self and identity among troubled adolescent youth. The CLP was implemented by the Miami Youth Development Project as a PYD psychosocial program targeting multi-problem youth in alternative high schools in the Miami Dade County Public Schools (M-DCPS), the fourth largest school system in the United States. The CLP is a long-standing community engaged, gender, and ethnic inclusive PYD psychosocial intervention. The CLP specifically targets these youths because students who come to alternative schools are on a negative life course pathway and at risk for multiple negative developmental outcomes and/or engaged in multiple problem behaviors.

The CLP provides an on-site (in school) psychosocial intervention in all of the M-DCPS voluntary alternative high schools. The primary intervention goal is to create contexts that empower troubled adolescents in ways the promote the development of a positive identity and, as described next, also result in positive change in problem outcomes, thereby changing their “negative” life pathways into positive ones.

Youth in alternative high schools are at increased risk for multiple problem behaviors (Grunbaum et al., 2000; Windle, 2003). Although the effects of treatment and prevention interventions on problem behaviors have been widely researched, evidence for PYD intervention effects (direct or cascading) on problematic outcomes is scant or nonexistent (Schwartz et al., 2007). The literature that has begun to emerge has largely focused on the potential direct effects of PYD programs in reducing internalizing problem behaviors (e.g., depression, anxiety, etc.) (McWhinnie, Abela, Hilmy, & Ferrer, 2008). There has been little research on the mediational processes by which these PYD effects may occur.

A main conceptual focus of the ongoing program of developmental intervention research on the Changing Lives Program (CLP) intervention has been on the theory informed selection of mediators and positive outcome variables, as well as a broad and representative array of problem outcome variables for evaluating CLP outcomes. The CLP uses a participatory transformative intervention process to target the formation of a positive sense of self and identity among multi-problem youth attending alternative high schools. Thus, this study used quantitative and qualitative indices of positive identity development drawn from the literature on self and identity.

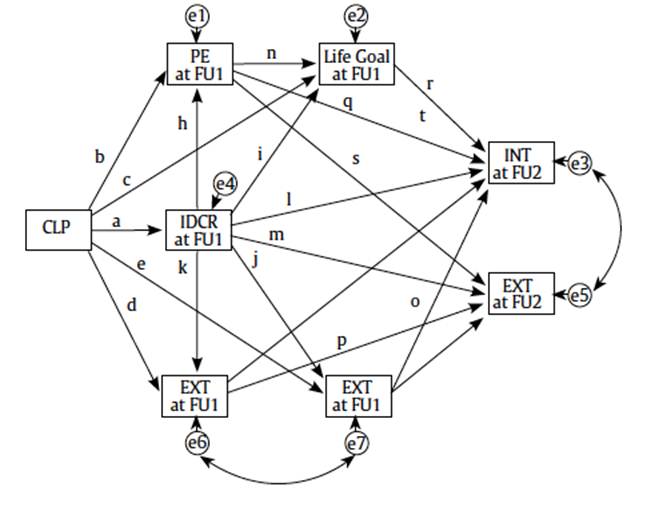

Figure 1 visually depicts the basic conceptualized pathways of intervention change, including (1) direct effects on positive identity outcomes, (2) direct effects on problem behavior outcomes, (3) indirect effects on positive identity and problem behavior outcomes mediated by hypothesized identity formation processes, and (4) indirect effects on problem behavior outcomes mediated by positive identity outcomes, that is, cascading positive change that spills over across positive and problem outcomes.

Hypothesized Pathways of Intervention Change: Direct, Mediated, and Cascade Effects

Figure 2 visually presents the Outcome Mediation Cascade (OMC) evaluation model used to investigate intervention effects (including measures of both positive and problem outcomes). Measured variables were selected to operationalize the conceptual model described above (see Measures section for a description of the measures).

Method

Participants

Participants for this study were drawn from the Changing Lives Program. In addition to a core family of measures (group administered self-report, individually administered open ended, and semi-structured interview measures, etc.), a core of specialty measures associated with specific evaluation projects (such as this study) were utilized. The sample for this study was comprised of 259 White/Non-Hispanic, African-American, and Hispanic adolescents. Due to under-representation, the 21 White/Non-Hispanic individuals were not included in the sample. Analyses were conducted with 238 African-American and Hispanic adolescents aged 14-18 who had completed the intervention, 98 of whom participated in a two-semester non-intervention (non-random) comparison control condition. The sample consisted of 137 females (87 African American, 50 Hispanic) and 101 males (52 African American, 49 Hispanic). With regard to the socio-economic characteristics of the sample, 38% of annual family incomes were below $21,000, while 17% were over $41,000. Seventy-four percent of the participants had at least one parent who completed high school, 50% had two parents who completed high school, and 31% had at least one parent who completed a bachelor’s degree.

Procedure

Intervention procedure. Following the Youth Development Project’s established procedures, each intervention group was led by an intervention team that consisted of one group facilitator, one co-facilitator, and one or two group assistants. All groups shared this structure and format. All group facilitators and co-facilitators were graduate level students enrolled in either a doctoral or a master’s level program. Group assistants were undergraduate psychology students who had been trained in the administration of the measures and in participant tracking procedures.

The group facilitators and co-facilitators served as counselors and used the CLP’s intervention strategy, a participatory transformative approach (Montgomery et al., 2008). The intervention groups met for approximately 45 minutes to 1 hour every week for approximately 8 to 12 weeks in either the fall or spring semester.

Assessment procedure. The students were assessed by undergraduate psychology students serving as research trainees. Their training took place at the beginning of each semester and included instruction concerning confidentiality issues, assessment administration, dress code, high school regulations, interviewing strategies, and role-playing of interviews. Assessments were conducted at three times during the school year on school grounds and during school hours. Assessments took place the week preceding the commencement of the semester sessions and the week after the end of each semester’s sessions.

Measures

Psychosocial mediator: Identity conflict resolution. The Erikson Psycho-Social Stage Index (EPSI; Rosenthal, Gurney, & Moore, 1981) is a 72-item self-report measure that includes six subscales, each consisting of 12 items indicating how well respondents have resolved conflicts indicative of Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development. This study used the identity conflict resolution subscale (IDCR). Items on this subscale utilize key words and statements from Erikson’s characterizations of the identity synthesis versus identity confusion stage. Sample items included “I know what kind of person I am.” Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (almost never true) to 5 (almost always true) with half of the items representing resolution of the identity crisis, and half representing identity confusion. Items representing identity confusion were reverse-coded prior to analysis. Thus, mean scores for the IDCR subscale yield an index of degree of resolution, with high scores indicating higher levels of resolution. Rosenthal et al. (1981) reported a correlation coefficient of .56 between the identity conflict resolution subscale of the EPSI and the identity subscale of Greenberger, Knerr, Knerr, and Brown (1974) Psychosocial Maturity Inventory (PSM), Form D. Alpha coefficients of .74 have been reported in an adolescent sample (Ferrer-Wreder, Palchuk, Poyrazli, Small, & Domitrovich, 2008) and in a large youth sample ranging across middle school through college (Montgomery, 2005). In this study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was .77.

Positive outcome: Feelings of personal expressiveness. The Personally Expressive Activities Questionnaire (PEAQ; Waterman, 1995) is a 14-item self-report measure that includes three subscales indicating feelings of personal expressiveness, hedonic enjoyment, and flow challenge. This study used the feelings of personal expressiveness subscale (PE) as a measure of differential intervention outcome in the positive domain. The PEAQ has been adapted for use in the evaluation of CLP such that questions refer to activities associated with the long-term life goals of the respondents. Thus, the PE subscale indicates the degree to which respondents feel that the pursuit of life goals is personally satisfying and expressive of their unique potentials. The PE subscale consists of six items, the scores of which are averaged to generate a subscale score. Sample items included “When I do these activities, I feel like it’s what I was meant to do.” Items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) (Waterman, 1995). Waterman (2004) found significant correlations between PE scores and identity status and identity style, providing evidence of concurrent validity. Waterman (2005) reported an alpha reliability coefficient of .77 for the PE subscale; in this study it was .91.

Positive outcome: Personally expressive life goals. The Personally Expressive Activities Questionnaire - Qualitative Extension (PEAQ-QE) (Rinaldi et al., 2012) adds an open-ended response component to the PEAQ to provide a method for eliciting the narrative/linguistic expressions of meaning and significance of participants’ most important life goals. Specifically, participants were asked to identify up to three life goals and then to identify their most important life goal. They were then asked to provide an open-ended description of its meaning and significance. More specifically, participants were asked “What does this life goal mean to you?” and “Why is this significant or important to you? How significant or important is this to you?” The meaning and significance questions were then followed by three neutral probes (e.g., “Can you say more about that?”, “Is there anything else?”) to request secondary elaboration when necessary.

Analysis of inter-coder agreement for level 1 subcategories indicated agreement of 96% and a Fleiss’ kappa of .84, suggesting almost perfect agreement (correcting for chance). The Personally Expressive category had two nested subcategories: Personally Expressive through Others and Personally Expressive through Self. The Non-Personally Expressive category had three nested subcategories: Prove to Others, Self-Satisfying, Benefit of Others; and two mixed nested subcategories: Mixed Prove to Others/Self Satisfying and Mixed Self Satisfying/Benefit of Others. Analysis of inter-coder agreement for level 2 subcategories indicated agreement of 86% and a Fleiss’ kappa of .69, suggesting substantial agreement (correcting for chance). Analyses of the full model used level 1 subcategories, that is, personally expressive versus non-personally expressive life goals (Life Goal).

Problem outcomes: Internalizing and externalizing problem behaviors. The Behavior Problem Index (BPI; Peterson & Zill, 1986) was used to assess internalizing and externalizing problem behaviors. The 32 items of the BPI were taken from the Achenbach Behavior Problems Checklist (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1981), a more extensive measure that is widely used with children and adolescents. The BPI items were included in the Panel Study of Income Dynamics - Child Development Supplement II (PSID-CDS II; Mainieri, 2006), a national survey of children and adolescents, to describe a number of behavior problem areas over the past 3 months, which are scored for Internalizing (INT) and Externalizing (EXT) problem behaviors. Mainieri (2006) reported Cronbach’s alphas of .86 for EXT and .83 for INT in the PSID-CDS II sample. Cronbach’s alphas for the present sample were .81 and .85 for the EXT and INT, respectively.

Moderators of outcome (gender and ethnicity). Background Information Form (BIF) is a record of demographic information completed by all participants in the YDP program. It provided the data used in analyses of gender and ethnicity (Hispanic/Latino, African American, Non-Hispanic White, Bi-ethnic, and Other) as exogenous moderators.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

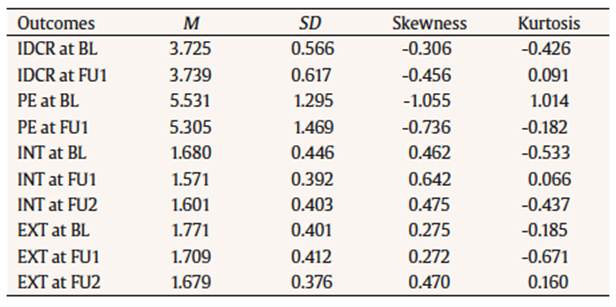

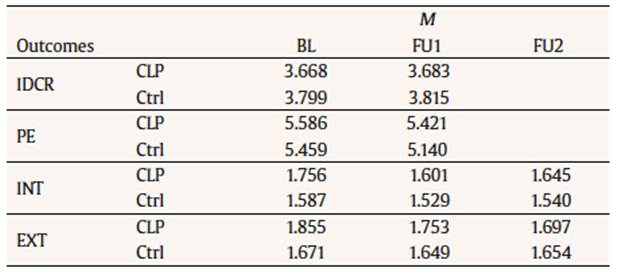

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis for the continuous outcome variables at Baseline (BL), Follow-up 1 (FU1), and Follow-up 2 (FU2). These include the subscales of the Personally Expressive Activities Questionnaire (PEAQ): Personal Expressiveness (PE); the Erikson Psycho-Social Stage Index (EPSI): Identity Conflict Resolution (IDCR); and the Behavior Problem Index (BPI): Internalizing (INT) and Externalizing (EXT) problem behaviors.

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics for Continuous Outcome Variables

Note. IDCR = Identity Conflict Resolution; BL = Baseline; FU1 = Follow-up 1; PE = Personal Expressiveness; INT = Internalizing; EXT = Externalizing; FU2 = Follow-up.

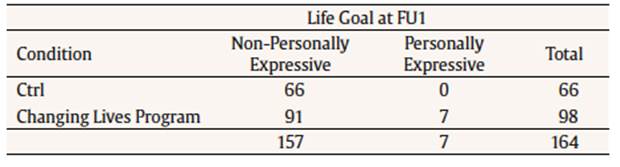

Table 2 presents the number and proportion of responses assigned to level 1 and level 2 subcategories of the Life Goal variable. Baseline evaluation indicated that 92% of descriptions of participants’ most important life goals had the non-personally expressive property and, more specifically, that the majority of responses (75%) had the self-satisfying property. This proportion was similar for both males and females and for both Hispanic and African American participants (ranging from 75% to 76% within each subgroup), as well as among age subgroups (ranging from 71% to 83%) The variation in proportions by age was not significant (x2 = 1.515, df = 4, p = .82).

Outliers, Missing Data, and Non-Normality

Prior to the study’s main analysis, data for the continuous variables were evaluated for outliers and normality. Outliers were evaluated by examining leverage statistics for each individual; an outlier was defined as an individual with a leverage score four times greater than the mean leverage. No outliers were found. Kurtosis and skewness were within acceptable ranges (see Table 1).

Main Analyses

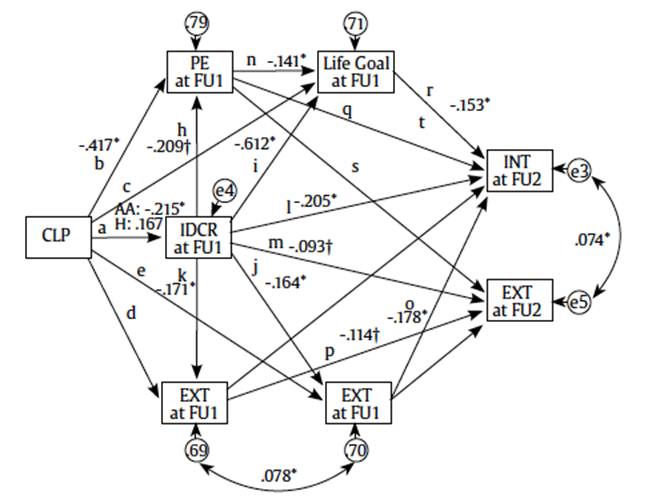

Model 1 (Figure 1), the hypothesized Outcome Mediation Cascade (OMC) model, was evaluated using a Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) approach for modeling hypothesized causal pathways of intervention change. Model specification was guided by Figure 2. Figure 3 and Tables 3 and 5 present the results (outcome, moderation, and mediation) for Model 1, including relations between the hypothesized mediator (IDCR), the two positive identity outcome variables (PE and Life Goal), and the two problem behavior outcome variables (INT and EXT) for the full sample.

Table 3 Summary of Major Path Analyses for Mediator and Positive Outcomes

Note. Standardized coefficients shown in parentheses. CLP = Changing Lives Program; E = Ethnicity; IDCR = Identity Conflict Resolution; PE = Personal Expressiveness.

Table 4 Mean Change in Continuous Outcomes

Note. Means are not adjusted for covariates. IDCR = Identity Conflict Resolution; CLP = Changing Lives Program; PE = Personal Expressiveness; INT = Internalizing; EXT = Externalizing

Interaction effects for the moderated relationships were tested using product terms (Jaccard & Turrisi, 2003). Two-valued dummy variables for two exogenous interpersonal contextual covariates, Gender (G) and Ethnicity (E), were included in the analysis of outcome as measured at pretest, as were all possible interaction terms (i.e., CLP*G, CLP*E, G*E, CLP*G*E), with CLP designated as the focal independent variable. Non-significant interactions were dropped from the final model, leaving one significant interaction term (CLP*E). To reduce clutter and improve visual clarity, the model in Figure 3 excludes the paths associated with E and CLP*E; however, the simple main effects are included in the model. Participants’ age and scores of outcomes at BL were included as covariates.

The fit of Model 1 was evaluated with Mplus 5.0 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998-2007) using the sample covariance matrix as input and a robust weighted least squares solution. The model is statistically overidentified. Data analysis used the robust WLSMV estimator available in Mplus in order to adjust the parameter estimates, standard errors, and fit indices for the categorical nature of the Life Goal variable. Computation of standard errors and the chi-square test of model fit took into account non-independence of observations due to cluster sampling, specifically to account for possible counseling group clustering effects.

Cases with incomplete covariate data were not included in the model analysis, resulting in a data set of 212 cases. These data were assessed for missingness and appear to meet the specified criteria. Although a high percentage of data for the FU2 evaluation was missing (42% missing for INT and EXT at FU2 and 9% or less missing data for FU1 variables), Little’s MCAR test was found to be non-significant (x2 = 26.980, df = 24, p = .31). In addition, dummy variables were created for missing data and correlated with gender, ethnicity, age, and school location, as well as all other variables included in the model. Missing data were not strongly correlated (all correlations were less than .17) with any of these variables.

Following recommendations of Bollen and Long (1993), a variety of global fit indices were used, including indices of absolute fit, indices of relative fit, and indices of fit with a penalty function for lack of parsimony. First, the chi-square and its probability value (p-value) were examined.

The overall chi square test of model fit of Model 1 was statistically non-significant, x2(7) = 6.991, p = .43. The RMSEA was .00, WRMR was .459, and the CFI was 1.00. Thus, fit indices were consistent with good model fit. The model in Figure 3 presents statistically significant paths in bold, while Tables 3 and 5 present the parameter estimates for the major analyses.

Hypothesized Direct and Moderated Intervention Effects

Following the logic of Rausch, Maxwell, and Kelly (2003), the scores of the baseline measures (PE, IDCR, Life Goal, INT, EXT) were used for the analysis of covariance of a quasi-experimental outcome design with two waves of assessment (BL, FU1) to evaluate whether participation in the CLP was associated with change in IDCR, PE, Life Goal, INT, and EXT relative to the comparison control condition. Specifically, CLP was defined as a two-valued dummy variable (scored 1 or 0) for the two intervention conditions (CLP vs. comparison control). By design, difference in this variable was hypothesized to be related to differential outcome (change in IDCR, PE, Life Goal, INT, EXT) at FU1 (IDCR, PE, Life Goal, INT, EXT) controlling for BL (IDCR, PE, Life Goal, INT, EXT). The hypothesized differences were evaluated using covariate-adjusted change in which the measure of the outcome at BL and the outcome at the FU1 are strategically used as covariates to define different features of change (Rausch et al., 2003).

As can be seen from Figure 3 and Table 3, the pattern of findings provided evidence of a significant relationship between CLP and change in PE (path b; b = .417, p < .01, 95% CI = 0.145 to 0.689). Exa- mination of group means indicates that PE scores for the intervention group decreased less than PE scores for the comparison control group (see Table 4 for mean change). For Life Goal, a personally expressive life goal (i.e., life goals with the personally expressive property) versus a non-personally expressive life goal (i.e., life goals without the personally expressive property) was also represented by a two-valued dummy variable (scored 1 = assignment to the Personally Expressive subcategory, 0 = assignment to the Non-personally Expressive subcategory). Results indicated that the direct relationship between CLP and change in Life Goal (path c) was not significant. As can be seen from Figure 3 and Table 5, the pattern of findings also did not provide evidence of significant relationships between CLP and changes in the untargeted problem outcome variables (INT and EXT; paths d and e).

Hypothesized Mediation of Positive Outcomes

Hypothesized mediation (see Figure 2) was evaluated with the joint significance test (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002) by significance of the paths associated with the causal chains between distal variables and change in hypothesized mediating variables (including positive outcomes hypothesized to mediate change in problem outcomes) and, in turn, the association between change in mediating variables and change in outcome variables. In addition, the baseline measures of the hypothesized mediators were modeled as covariates for the outcomes variables (and thus held constant) in order to model the relationship between change in mediators and change in outcomes. All hypothesized mediated relationships were modeled in this manner; these paths were not included in Figure 3 to improve visual clarity.

CLP had a statistically significant relationship with change in IDCR, the hypothesized mediator. Specifically, the path coefficient for the relationship between CLP and change in IDCR was statistically significant, but the relationship was moderated by E, indicating a moderated specificity of effect. The 2-way CLP x E interaction term had a statistically significant coefficient when predicting change in IDCR (b = .368, p < .01, 95% CI = 0.102 to 0.633), indicating that intervention change in IDCR differed between ethnic groups. Among Hispanic participants, the path coefficient for the relationship between CLP and change in IDCR was not significant (path a; b = .167, p = .15, 95% CI = -0.060 to 0.394). Among African American participants, the path coefficient was significant (path a; b = -.215, p < .001, 95% CI = -0.309 to -0.120), indicating that the intervention group decreased in IDCR relative to the comparison control group.

Findings provided support for IDCR as a plausible moderated mediator of the relationship between CLP and change in PE and between CLP and qualitative change in Life Goal. Findings indicated that BL to FU1 change in IDCR was marginally significantly associated with contemporaneous change in PE (path h; b = .209, p < .08, 95% CI = -0.022 to 0.440). The confidence interval for the indirect effect of the CLP*E product term was computed using the PRODCLIN program (MacKinnon, Fritz, Williams, & Lockwood, 2007) and provided further support for moderated mediation (product = .077, Sobel SE = .052, 95% CI = -0.324 to -0.026).

The relationship between IDCR and Life Goal was modeled using the latent response formulation for categorical outcomes as implemented in Mplus 5.0 with the WLSMV estimator (Muthen & Muthen, 1998-2007). The probit regression coefficients generated by the analysis were interpreted in terms of probability units (i.e., probits) and reflect the relationship between a one unit change in a mediator and the probability that Life Goal = 1 (see Agresti, 2007). This approach models the observed categorical response variable as the realization of a latent continuous response variable. Specifically, the observed ordinal value changes when a probit threshold is exceeded on the latent continuous variable (Muthen & Muthen, 1998-2007). In the case of the dichotomous Life Goal variable, there is a single probit threshold for the latent continuous variable such that Life Goal = 1 (Personally Expressive) when this threshold is exceeded and Life Goal = 0 (Non-personally Expressive) when the threshold is not exceeded. Findings indicated that change in IDCR was significantly associated with the probit of contemporaneous change in Life Goal (path i; b = -.612, p < .01, 95% CI = -1.009 to -0.214). The indirect effect of CLP*E was significant (product = -.225, Sobel SE = .112, 95% CI = -0.579 to -0.058). The relationship between PE and Life Goal was modeled in the same manner; change in PE was significantly associated with the probit of contemporaneous change in Life Goal (path n; b = .141, p = .01, 95% CI = 0.033 to 0.249).

Hypothesized Mediation of Problem Outcomes

Findings provided support for IDCR as a moderated mediator of the relationship between CLP and changes in INT and EXT. Findings indicated that BL to FU1 change in IDCR was significantly associated with contemporaneous change in INT (path j; b = -.164, p < .001, 95% CI = -0.238 to -0.090) and EXT (path k; b = -.171, p < .001, 95% CI = -0.236 to -0.105). In addition, BL to FU1 change in IDCR was significantly associated with change in INT at FU2 (path l; b = -.205, p = .001, 95% CI = -0.328 to -0.083), and the indirect effect of CLP*E was significant (product = -.075, Sobel SE = .036, 95% CI = -0.180 to -0.018). Change in IDCR was marginally significantly associated with change in EXT at FU2 (path m; b= -.093, p < .06, 95% CI = -0.187 to 0.002), and the indirect effect CLP*E was significant (product = -.034, Sobel SE = .022, 95% CI = -0.135 to -0.013).

Hypothesized Cascade Effects

With regard to hypothesized cascade effects, that is, intervention effects in untargeted problem outcomes mediated by change in targeted positive outcomes, analyses provided support for three plausible causal chains that represent intervention cascade effects mediated by qualitative change in life goals. The findings provided support for Life Goal as a mediator of the relationship between CLP and INT as part of the pathways CLP -> IDCR -> Life Goal -> INT (paths a, i, r), CLP -> PE -> Life Goal -> INT (paths b, n, r), and CLP -> IDCR -> PE -> Life Goal -> INT (paths a, h, n, r). Specifically, change in Life Goal was significantly related to change in INT (path r; b = -.153, p = .001, 95% CI = -0.241 to -0.066).

Qualitative Change in Life Goal: Fine-grained Analyses

Due to the large proportion (75%) of participants with a self-satisfying life goal at baseline, finer-grained analyses of the relationship between CLP and Life Goal at FU1 (path c) were pursued. Limited information tests of conditional independence for CLP and Life Goal at FU1 indicated that this relationship was not significant for participants with a non-personally expressive life goal at BL, x2(1) = .487, p = .49; p = .56, Fisher’s exact test, 95% CI = 0.397 to 7.253, or for those with a personally expressive life goal at BL (p = 1.00, Fisher’s exact test, 95% CI = 0.092 to 10.881).

However, CLP was significantly associated with Life Goal at FU1 among participants with a self-satisfying life goal at BL, x2(1) = 4.925, p = .03; p = .04, Fisher’s exact test, 95% CI = 1.001 to ∞). As indexed by a fourfold point correlation coefficient, the strength of the relationship was .218. This reflects primarily that, among participants with a self-satisfying life goal at BL, CLP participants’ responses at FU1 were more likely to have the personally expressive property than expected and that comparison control participants’ responses at FU1 were less likely to have the personally expressive property than expected (see Table 6). Of the 66 comparison control group participants with a self-satisfying life goal at BL, zero described life goals at FU1 with the personally expressive property. Of the 98 CLP participants with a self-satisfying life goal at BL, seven described life goals at FU1 with the personally expressive property.

Discussion

This paper contributes to the evaluation of the theoretical and empirical utility of integrating developmental and intervention science in the service of promoting positive youth development (PYD). Rooted in concepts and constructs drawn from applied developmental science (Lerner, Fisher, & Weinberg, 2000), the aims of developmental intervention science include the development and evaluation of evidence-based intervention strategies that draw on developmental and intervention science in promoting positive development and in reducing problem behaviors. Using this approach, a study was conducted to evaluate the hypothesized cascade effects of a PYD psychosocial intervention that specifically targeted positive identity development in at-risk adolescents. The investigation used an Outcome Mediation Cascade (OMC) model that expanded the outcome mediation model described in the treatment literature (Silverman, Kurtines, Jaccard, & Pina, 2009) by adding features of the developmental cascade model described in the developmental psychopathology literature (Cicchetti & Cohen, 2006; Masten et al., 2005). Intervention developmental cascades were conceptualized as intervention gains in positive outcomes that “spill over” to generate reductions in problem outcomes. These analyses contributed to advancing our knowledge (both theoretical and empirical) of how interventions work.

Does It Work? Positive and Problem Outcomes

With respect to hypothesized positive and problem outcomes, the evaluation of the OMC model’s fit to the data yielded results that were promising at many different levels. The findings provided empirical support for the hypothesis that participation in the intervention has significant effects on both of the study’s positive outcome variables. First, the evaluation of the CLP indicated that participation in the intervention was associated with a differential change consistent with the hypothesized aims of the intervention in participants’ feelings of personal expressiveness, a measure of a core emotion-focused component of positive identity, relative to comparison control group participants. Feelings of personal expressiveness (PE) reflect the degree of fit between the pursuit of life goals and participants’ unique potentials.

Second, the full information investigation of the OMC evaluation model did not provide evidence of a direct intervention effect on the probability of a personally expressive life goal, a marker of an increasingly integrated and complex self-structure. Limited information tests of conditional independence among participants with a personally expressive life goal at BL and among participants with a non-personally expressive life goal at BL also did not provide evidence of a direct intervention effect. However, a finer-grained limited information test of conditional independence, focusing specifically on differential intervention effect on the presence/absence of a personally expressive life goal at FU1 among participants with a self-satisfying life goal at BL (a group that included the majority, 75%, of the sample) did provide evidence for a direct differential effect between the intervention condition and the control. Thus, although both of the intervention and comparison control conditions had zero personally expressive life goals at BL (because BL designations were held constant, i.e., all self-satisfying life goals are non-personally expressive), seven of 98 CLP participants had a personally expressive life goal at FU1 while the 66 comparison control group participants still had zero personally expressive life goals at FU1. In addition, full information investigation of the OMC model indicated that an increase in feelings of personal expressiveness was associated with an increase in the probability of a personally expressive life goal.

With respect to intervention effects on problem outcomes, the results did not provide evidence of direct intervention effects on untargeted internalizing or externalizing problem behaviors. The findings, however, did suggest several mediated and cascading causal pathways through which the intervention had an effect on problem outcomes, described below. In addition, results suggested that internalizing and externalizing problem behaviors were linked over time. A BL to FU1 increase in externalizing problem behaviors predicted a FU1 to FU2 increase in internalizing problem behaviors, and a BL to FU1 increase in internalizing problem behaviors predicted a FU1 to FU2 decrease in externalizing problem behaviors.

How Does It Work? Mediation of Positive and Problem Outcomes

The pattern of results of this study’s mediation analyses yielded some interesting and suggestive potential answers to the theoretical question of how the intervention works to promote change in positive and problem outcomes. Engagement in identity crisis was conceptualized as a mediator of change in both positive and problem outcomes among adolescents in the early stages of the identity process. A measure of the resolution of conflicts indicative of the identity crisis was used to assess change in this hypothesized mediator; a decrease in identity conflict resolution was conceptualized to reflect increased identity processing as a prelude to identity exploration.

The pattern of results provided support for the hypothesis that identity conflict resolution mediates intervention effects on positive and problem outcomes. Specifically, results indicated that participation in the CLP was associated with a BL to FU1 decrease in identity conflict resolution among African American participants, relative to the comparison control group, but not among Hispanic participants. Results further indicated that BL to FU1 change in identity conflict resolution was associated with BL to FU1 change in feelings of personal expressiveness, the probability of a personally expressive life goal, and internalizing and externalizing problem behaviors. In addition, BL to FU1 change in identify conflict resolution was associated with FU1 to FU2 change in internalizing and externalizing problem behaviors. Thus, the findings provided support for identity conflict resolution as a moderated mediator of contemporaneous changes in feelings of personal expressiveness (CLP -> IDCR -> PE; path a, h), the probability of a personally expressive life goal (CLP -> IDCR -> Life Goal; path a, i), internalizing problem behaviors (CLP -> IDCR -> INT; path a, j) and externalizing problem behaviors (CLP -> IDCR -> EXT; path a, k) and progressive changes in internalizing problem behaviors (CLP -> IDCR -> INT; path a, l) and externalizing problem behaviors (CLP -> IDCR -> EXT; path a, m).

In the context of our working hypothesis that both PYD and prevention perspectives “work” by promoting positive change in person context relations (Schwartz et al., 2007), the finding that change in identity conflict resolution mediated all of this study’s positive and problem outcomes is particularly intriguing. The possibility that changes in psychosocial dimensions indicate changes in the person context relations targeted by PYD and prevention interventions is in line with Theokas et al.’s (2005) findings highlighting the lack of pure discrimination between positive identity and connections with social contexts, as well as Erikson’s (1963) description of identity as an inward and outward sense of continuity and sameness. However, the conclusions that can be drawn from the current findings are limited. Future research should consider pursuing this issue, for example, by investigating person context relations that result in identity conflict or identity deficit, because this line of inquiry has the potential to refine current knowledge of effective intentional person context intervention processes.

Does Positive Cascading Change Reduce Problem Behaviors? Intervention Developmental Cascades

This study operationalized the concept of an intervention developmental cascade as the statistical mediation of the relationship between participation in the CLP intervention and differential change in problem behavior outcomes (internalizing and externalizing) by differential change in positive identity outcomes (feelings of personal expressiveness and the probability of a personally expressive life goal). The analyses identified several causal pathways through which change in feelings of personal expressiveness and the presence/absence of a personally expressive life goal mediated the effects of the intervention on progressive change in internalizing problem behaviors.

Findings provided support for significant differential quantitative change in feelings of personal expressiveness and theoretically meaningful qualitative (categorical) change in participants’ most important life goals as mediators of progressive change in internalizing problem behaviors through several causal pathways. The qualitative change in participants’ life goals from non-personally expressive to personally expressive from BL to FU1 was associated with a decrease in internalizing problem behaviors from FU1 to FU2. Thus, findings provided support for change in feelings of personal expressiveness and qualitative change in participants’ life goals as mediators of progressive change in problem behaviors via the following pathways: CLP -> PE -> Life Goal -> INT (path b, n, r), CLP -> IDCR -> PE -> Life Goal -> INT (path a, h, n, r), and CLP -> IDCR -> Life Goal -> INT (path a, i, r).

These findings make an initial contribution to closing the gap in our knowledge of the relationship between intervention change in positive outcomes and intervention change in problem outcomes. They provided preliminary evidence consistent with the hypothesis that in addition to having an effect on targeted positive outcomes, PYD interventions are likely to have progressive cascading effects on untargeted problem outcomes, that is, mediated intervention effects on problem outcomes that operate through effects on positive outcomes. The pattern of findings was also consistent with the hypothesis that the causal effects that are generated for both positive and problem outcomes are likely to follow complex pathways that interact in multifaceted ways with moderator and mediator variables rather than solely flowing directly from intervention to positive outcomes.

Directions for Future Research: Refining the OMC Evaluation Model

The findings raise a number of questions regarding the relationship between intervention change in positive outcomes and intervention change in problematic outcomes. For example, the finding that an increase in identity conflict predicted increases in problem behaviors and an increase in the probability of positive qualitative change in life goals suggests a seemingly straightforward question: should PYD psychosocial interventions seek to promote identity exploration even if the identity conflict that prompts exploration predicts problem behaviors in the short-term? As noted, identity exploration (or crisis) has been described as the “work” of the identity process (Grotevant, 1987) and has been consistently found to co-occur with problematic outcomes (Kidwell et al., 1995; Luyckx, Goossens, & Soenes, 2006; Schwartz, Mason, Pantin, & Szapocznik, 2008).

The findings from this study do not offer a satisfying answer to the question. However, the findings suggest that integrating the analysis of quantitative data with the analysis of qualitative data expanded the range of possible answers beyond the rather narrow conceptualization of identity exploration as either maladaptive or adaptive. These findings instead invite speculation about the personal meaning and significance of the identity choices faced by the adolescent, or even of behaviors researchers describe as internalizing and externalizing problems.

Limitations and Future Directions

Missing Data and Participant Attrition

At the time of this study, research regarding participant attrition in the CLP is unavailable, though attrition is known to be considerable. The alternative high schools from which the sample was drawn do not record their own attrition data (Albrecht, 2007); however, Miami-Dade County Public Schools (M-DCPS) reports county-wide graduation rates of approximately 59% and an official drop-out rate of 4.5%. On-time graduation rates are reported at 45.3% (Toppo, 2006). None of these figures account for students who are not officially withdrawn. Because little specific information is available regarding these students, it is possible that selection effects are potentially biasing results. Future CLP research should begin to address this issue.

The missing data found in the analyses may be due to the nature of the population the intervention targets, i.e., a population composed of multi-problem adolescents in alternative high schools, many of whom are coming of age in disempowering contexts. This population faces risk factors that contribute to poor attendance among other psychosocial problems that result in highly variable school/class attendance and high attrition rates. However, participant attrition is one source of missing data among many potential sources of missing data. A better understanding of the role that attrition plays in generating observed missing data patterns, as well as a more nuanced understanding of the factors underlying participant attrition, will allow future researchers to proactively model missing data mechanisms. A number of sources (e.g., Collins, Schafer, & Kam, 2001; Graham, 2009; Little, 1995) have suggested modeling auxiliary variables useful in predicting missing values, and Mplus (Muthen & Muthen, 1998-2007) includes a feature for doing so. Future studies may need to model these auxiliary variables in order to investigate the potential effects of attrition in psychosocial interventions that target identity.

Mediated Moderation or Moderated Mediation?

One possible refinement to the investigation of the OMC evaluation model is to undertake a more comprehensive analysis of moderation of intervention cascade effects by relevant contextual factors. The moderation analyses conducted by this study represent an initial attempt to identify relevant contextual moderators of intervention effects. The finding that a number of the cascade pathways identified by the analyses were moderated by ethnicity suggests the need for further research regarding the nature of this moderation. One question for future research is whether this moderation is better conceptualized as mediated moderation or as moderated mediation.

As a number of researchers (e.g., Edwards & Lambert, 2007; Iacobucci, 2008; Muller, Judd, & Yzerbcyt, 2005) have pointed out, there is overlap in the strategies for evaluating mediated moderation and moderated mediation. Mediated moderation refers to an interaction between an independent variable and a moderator variable that has an effect on a mediator variable that, in turn, has an effect on an outcome variable. Thus, the effect of the interaction between CLP and ethnicity on identity conflict resolution and the effects of identity conflict resolution on the probability of a personally expressive life goal, internalizing problem behaviors, and externalizing problem behaviors may all reflect mediated moderation. On the other hand, the effect of the interaction between CLP and ethnicity on identity conflict resolution and the effects of identity conflict resolution on the probability of a personally expressive life goal, internalizing problem behaviors, and externalizing problem behaviors could reflect moderated mediation because in this scenario mediated moderation and moderated mediation are analytically equivalent.

With respect to the analytic goals of an investigation of hypothesized intervention developmental cascade effects, the most pertinent research question appears to be whether or not the hypothesized cascading dynamic depends upon potential contextual moderators (such as ethnicity), i.e., a question of moderated mediation. This study, however, did not examine moderation of the effect of identity conflict resolution on the probability of a personally expressive life goal, internalizing problem behaviors, and externalizing problem behaviors.

Future research regarding moderation of intervention cascade effects should draw on Edwards and Lambert’s (2007) model to investigate contextual moderation by examining second stage moderation (moderation of the relationship between the mediator/positive outcome and the outcome/problem behavior) in addition to direct effect moderation (moderation of the relationship between participation in the intervention and the outcome/problem behavior) and first stage moderation (moderation of the relationship between participation in the intervention and the mediator/positive outcome).

What do Problem Behaviors Mean to the Adolescent?

While refinement of the analyses has the potential to enhance the present findings, perhaps more clarity may be gained by refining the research questions themselves. Among the potential new research questions raised by this study is whether the use of qualitative methods designed to capture the structural organization of the subjective meaning and significance of internalizing and externalizing behaviors would contribute to the evolution of more empirically supported theory informed models of both short and long-term developmental change (identity).

Siegel and Scovill (2000) argue that problem behaviors are viewed most productively in their double aspect, or as a double symptom, with a positive aspect that reflects adolescents’ attempts to find an appropriate pathway to satisfy their developmental needs and accomplish developmental tasks successfully. While the negative aspect of problem behaviors is well documented, the hypothesized positive aspect has less often been the object of investigation. Similar to Luyckx et al.’s (2008) identification of adaptive and maladaptive identity exploration, this argument appears to reflect the recognition of subjectively meaningful qualitative differences in problematic behaviors. As Siegal and Scovill point out, different behaviors have different meanings for different adolescents. Moreover, “Adolescents, like adults do things for a reason. Behaviors that adults label ‘dysfunctional’ or ‘inappropriate’ may be the same behaviors that help the adolescent survive in his environment” (p. 785). Siegal and Scovill cite extant research that has suggested that the perceived benefits of these behaviors play a central role in the behaviors.

An examination of theoretically meaningful qualitative structural organizational change in the subjective meaning and significance of internalizing and externalizing behaviors requires the collection of new data. The instrument for collecting this type of data may resemble the qualitative extension of the Personally Expressive Activities Questionnaire used in this study.

Study Design

Although the findings of this study indicate contemporaneous effects on positive identity via identity distress, the limitations of this study’s design may have masked the possibility of even greater delayed or lagged effects. Specifically, the development of a positive sense of self and identity is likely to continue well after participation in the CLP. Inclusion of future time points may reveal greater intervention effects (i.e., direct effects) on the development of a positive sense of self and identity. Additionally, a note of caution should be taken in regards to the generalizability of these findings. The current study was conducted at several alternative high schools in Miami that unlike more traditional educational institutions, is predominantly a school that focuses on at-risk populations. Moreover, it is important to note that the study took place with a diverse student population that may face cultural identity issues. For these adolescents who may be faced with deciding how to adapt their cultural identities and maintain a personal identity, identity-focused interventions may be more effective and imperative. Future studies should also examine the effectiveness of the CLP in encouraging cultural identity development.

Statistical Power and Sample Size Considerations

To determine an appropriate sample size, structural equation modeling requires that in addition to statistical power, issues of the stability of the covariance matrix and the use of asymptotic theory be taken into account. In terms of power, it is difficult to evaluate the power associated with specific path coefficients in complex SEM models because of the large number of assumptions about population parameters that must be made. In the case of this study, with a sample of 212 used for the full information analyses, there was an effect on the statistical power available for analyses of the full model, especially with respect to analyses of dichotomous outcomes that require large sample sizes to capture the relationship, if any, between the independent and dependent variables, thereby increasing the likelihood of the occurrence of type II errors, i.e., the inability to detect small effects. Limited information strategies were used to further probe these relations; however, these strategies are problematic in that they do not use all available information from the hypothesized model. Future studies may want to include larger sample sizes.

Practical Implications: A Ready at Hand Intervention

Efforts to identify effective positive development strategies are ongoing; however, the current study has important implications. Recent studies have highlighted the development of a positive sense of self and identity as a potential intervention target, capable of facilitating mental health and reducing or preventing various negative psychosocial outcomes (i.e., internalizing symptoms, externalizing problems, and health risk behaviors). The CLP, demonstrates the need for interventions to target identity as a main intervention goal, and moreover works as an easily transportable and ready at hand program that can be used at any institution for fostering positive development. The pattern of findings revealed in this study provides support for the model explored in the investigation of the CLP. These findings suggest that identity focused psychosocial interventions can provide opportunities for minority youth growing up in disempowering community contexts to discover their personal potentials and create their own solutions to life challenges. Providing opportunities for marginalized youth to expand and enhance the aspects of their lives that are meaningful to them can empower these youths to define for themselves the direction of their own positive development (Eichas, Montgomery, Meca, & Kurtines, 2017).

Conclusions

This study represents the first evaluation of hypothesized intervention cascade effects. A main contribution of this study was to provide empirical evidence for intervention developmental cascades, specifically effects on positive identity outcomes that “spill over” to generate change in problem behaviors. This cascading dynamic was investigated by analyzing mediation of intervention effects on problem behaviors by positive identity outcomes. The intervention had significant effects on both positive identity outcomes, and both positive identity outcomes mediated intervention effects on problem behaviors. In addition, change in the hypothesized mediator was a significant mediator of change in all positive and problem outcomes. The relationship between the intervention and change in the mediator was moderated by ethnicity. Future research is needed to evaluate moderation of intervention developmental cascades.

A second contribution of this study was to demonstrate an integrated analysis of quantitative dimensional change and qualitative structural organizational change using structural equation modeling techniques. Previous studies (Arango et al., 2008; Kortsch et al., 2008; Kurtines, Montgomery, Arango, & Kortsch, 2004) have used small samples to investigate qualitative intervention change in the narrative/linguistic expressions of the subjective experience of self and identity. However, the present study was the first to conduct a quantitative and qualitative evaluation model then use a path model and to test the fit of the data. This approach allowed the simultaneous modeling of multiple pathways of intervention change, including direct, mediated, and moderated effects, as well as cascade effects. The analysis used a continuous latent response formulation as implemented in Mplus (Muthen & Muthen, 1998-2007) to model categorical outcomes within an SEM framework.

A third contribution of the study was to test specific hypothesized relationships (direct, mediated, moderated) among theoretically meaningful qualitative structural organizational change in the subjective meaning and significance of participants’ most important life goals, quantitative dimensional positive and problematic outcomes, and participation in the CLP. Findings suggested (1) that an increase in identity conflict resolution was associated with a decreased probability of a personally expressive life goal; (2) that an increase in feelings of personal expressiveness generated by life goal pursuit was associated with an increased probability of a personally expressive life goal; (3) that the change from a non-personally expressive life goal to a personally expressive life goal was associated with a progressive decrease in internalizing problem behaviors; and (4) that participation in the CLP was associated with change from a non-personally expressive life goal to a personally expressive life goal among participants with a self-satisfying life goal at baseline evaluation.

The pattern of these findings likely reflects the complex and contingent nature of the systematic, successive, and adaptive developmental processes involved in constructing and re-constructing a positive sense of self and identity during initial stages of formation. The pattern of these findings further highlights the need for an expanded toolbox of the models and methods, particularly those capable of richly reflecting rather than reducing the life course experiences of youth and rendering explicit and intelligible the theoretical meaning of these experiences. This study represents an initial attempt to contribute to the array of tools available in developmental intervention research and to identify potential directions for future use and further refinement of these tools.