Introduction

Research has traditionally captured parenting styles using two dimensions: parental warmth and parental strictness (Darling & Steinberg, 1993; Smetana, 1995; Steinberg, 2005). The parental warmth dimension refers to the extent to which parents show their children care and acceptance, support them, and communicate with them (mirroring other traditional labels such as responsiveness, assurance, implication, or involvement). The parental strictness dimension reflects the extent to which parents impose standards for their children’s conduct (mirroring other traditional labels such as demandingness, domination, hostility, inflexibility, control, restriction, or parental firmness) (Darling & Steinberg, 1993; García & Gracia, 2009; Steinberg, 2005; Maccoby & Martin, 1983). Based on these two dimensions, four parenting styles have been identified: authoritative (warmth and strictness), authoritarian (strictness without warmth), indulgent (warmth without strictness), and neglectful (neither warmth nor strictness) (Darling & Steinberg, 1993; García & Gracia, 2009; Lamborn, Mounts, Steinberg, & Dornbusch, 1991; Maccoby & Martin, 1983; Smetana, 1995; Steinberg, 2005).

Numerous studies have repeatedly observed that authoritative parenting (warmth and strictness) represents the highest parent-child relationship quality, as it has been associated with optimum developmental outcomes for children and adolescents from middle-class European-American families (e.g., Baumrind, 1971; Lamborn et al., 1991; Steinberg, Lamborn, Darling, Mounts, & Dornbusch, 1994). The positive influence of this parenting style has been considered to expand even beyond adolescence, as some studies have associated authoritative parenting in childhood with positive functioning in late adulthood (e.g., Rothrauff, Cooney, & An, 2009; Stafford et al., 2015). From this perspective, warmth and strictness (which characterize the authoritative parenting style) are considered to be critical for the optimal development of children and adolescents (Baumrind, 1983; Kerr & Stattin, 2000; Lewis, 1981; Stattin & Kerr, 2000). Warmth would provide emotional support (acceptance, involvement, and support) and strictness would provide clear guidelines and behavioral limits to their children behavior (Baumrind, 1971; Steinberg, 2001). In fact, these and other studies conducted in countries with a variety of cultural values led Steinberg (2001) to consider that the benefits of authoritative parenting transcended the boundaries of ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and household composition (García & Gracia 2009).

Is the Optimum Parenting Style always Authoritative?

As García and Gracia (2009, 2014) noted, the available evidence does not support the idea that the optimum parenting style is always authoritative. A growing body of research is consistently questioning the view that an authoritative parenting style is always associated with positive developmental outcomes in children across all ethnicities, environments, and cultural contexts (Baumrind, 1972; Chao, 1994; Deater-Deckard, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1996; Dwairy & Achoui, 2006; García & Gracia, 2009, 2014; Gracia, Fuentes, García, & Lila, 2012; Lund & Scheffels, 2018; Martínez & García, 2007, 2008; Valente, Cogo-Moreira, & Sanchez, 2017; Wang & Phinney, 1998; White & Schnurr, 2012; Wolfradt, Hempel, & Miles, 2003). Different but related lines of argument have been suggested to explain the conflicting evidence questioning the universal optimal quality of the authoritative parenting style.

From the perspective of the Person-Environment Fit model, following the ideas of the ecology of human development (Bronfenbrenner, 1986), studies have suggested that people fit better and are more satisfied in environments that share their attitudes, values, and experiences. As poor ethnic minority families are more likely to live in dangerous communities, authoritarian parenting may not be as harmful, and it may even have some protective benefits in hazardous contexts (Furstenberg, Cook, Eccles, Elder, & Sameroff, 1999). For example, authoritarian child-rearing practices in African American communities are associated with caring, love, respect, protection, and the benefit of the child (e.g., Randolph, 1995). In an environment where the consequences of disobeying parental rules may be serious and harmful to the self and others, an authoritarian parenting style might even be as functional as other parenting styles (Clark, Yang, McClernon, & Fuemmeler, 2015; Deater-Deckard et al., 1996). Parenting and its consequences are also context-dependent, as they can be influenced by neighborhood characteristics and processes (Bowen, Bowen, & Cook, 2000; Brody et al., 2003; Gracia & Herrero, 2006; Gracia, López-Quílez, Marco & Lila, 2017; Gracia et al., 2012; Leventhal, & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Lila & Gracia, 2005; Simons et al., 2002).

The macro-social concepts of individualism and collectivism (vertical and horizontal) have also been called upon to explain differences observed in the association between parenting styles and children’s outcomes (e.g., Rudy & Grusec, 2001, 2006; Singelis, Triandis, Bhawuk, & Gelfand, 1995). On the one hand, studies in collectivist cultures, such as Asian and Arab societies, show that children understand the individual self as part of the family self. In these societies, relationships between generations are expected to be vertical and hierarchical, assuming strictness and imposition as a main part of parental responsibility. Strict authoritarian discipline is perceived as beneficial for the children, and its absence would be regarded as a lack of supervision and care (Dwairy & Achoui, 2006; Grusec, Rudy, & Martini, 1997).

On the other hand, studies carried out mainly in Spain and Brazil, suggest that in horizontal collectivist cultures the self is also conceptualized as part of a broad group (the family) but, unlike hierarchical cultures, the group is organized in an egalitarian way, rather than on a hierarchical basis (García & Gracia, 2009; Martínez & García, 2007, 2008; White & Schnurr, 2012). Horizontal collectivist cultures emphasize egalitarian relations, and more attention is placed on the use of affection, acceptance, and involvement in children’s socialization. Additionally, in these cultures, strictness and firm control in the socialization practices seem to be perceived in a negative way (García & Gracia, 2009; Gracia & Herrero, 2008; Martínez & García, 2007; Martínez, Murgui, García, & García, 2019; Rudy & Grusec, 2001). In this regard, emergent research conducted in these cultural contexts questions whether the parental strictness and imposition component of the authoritative parenting style is actually needed for optimal parenting, suggesting that an indulgent parenting style could be as optimum, or even more, than the authoritative parenting style (Calafat, García, Juan, Becoña, & Fernández-Hermida, 2014; García & Gracia, 2009; Lund & Scheffels, 2018; see García & Gracia, 2014; Pinquart & Kauser, 2018, for reviews).

Furthermore, recent evidence suggests that also in traditional vertical individualist societies (e.g., Great Britain) and horizontal individualist societies (e.g., Sweden), strictness practices do not seem to be effective, and high levels of reasoning, parental affection, acceptance, and involvement appear to be sufficient for an effective socialization (e.g., Calafat et al., 2014; García & Gracia, 2009; Lund & Scheffels, 2018). Without the authoritative component of high levels of strictness, also in these societies the indulgent parenting style would emerge as an optimal one. A study conducted with a large sample of adolescents from different European countries (Sweden, Slovenia, Czech Republic, UK, Spain, and Portugal) found that, regardless of the country, both the authoritative and the indulgent parenting style were equally protective against drug use. However, the indulgent parenting style performed better than the authoritative parenting style in terms of self-esteem and school performance, even in samples from two prototypical individualist countries in Northern Europe (e.g., UK and Sweden) (see Calafat et al., 2014; Lund & Scheffels, 2018). Furthermore, analyzing the influence of parenting beyond the adolescence, a recent study with samples from the UK found that high parental care was positively related to well-being, self-esteem, and social competence, regardless of the level of strictness, with a common short- and long- term pattern (from adolescence to early older age) (Stafford, Kuh, Gale, Mishra, & Richards, 2016). This emergent body of research suggest that the parental dimension key for optimal socialization outcomes is parental warmth, and that the parental strictness dimension of parenting appears not to be beneficial, but even harmful (García & Gracia, 2009; Grusec, Danyliuk, Kil, & O’Neill, 2017).

The Present Study

This study aims to examine the relationship between parenting styles and short- and long-term socialization outcomes among adolescents and older adults in Spain (Martínez & García, 2007, 2008; White & Schnurr, 2012). Two socialization outcomes will be analyzed: self-esteem and internalization of social values. Both outcomes are central objectives of parental socialization (Grusec & Goodnow, 1994). Self-esteem has been one of the traditional positive socialization outcomes analyzed in parenting studies (e.g., Rudy & Grusec, 2006) and is considered as a key indicator of personal adjustment and well-being (Klein, 2017; Meléndez-Moral, Fortuna-Terrero, Sales-Galán, & Mayordomo-Rodríguez, 2015; Musitu, Jimenez, Murgui, 2007; Riquelme, García, & Serra, 2018; Veiga, García, Reeve, Wentzel, & García, 2015). The internalization of social values is another important socialization outcome (Grusec et al., 2017; Grusec et al., 1997; Rudy & Grusec, 2001). Internalization of values, defined as “taking over the values and attitudes of society as one’s own so that socially acceptable behavior is motivated not by anticipation of external consequences but by intrinsic or internal factors” (Grusec & Goodnow, 1994, p. 4), has been established as a key indicator of successful socialization that fosters empathy and consideration for others, and is important for adult development (e.g., Baumrind, 1983; Darling & Steinberg, 1993; Fung, 2013; Hoffman, 1970; Lewis, 1981; Sortheix & Schwartz, 2017; Williams, Ciarrochi, & Heaven, 2015).

In this study we will also examine the link between parenting styles and short- and long-term socialization outcomes. Limited work has analyzed parenting influences on socialization outcomes beyond adolescence (Rothrauff et al., 2009; Stafford et al., 2015; Stafford et al., 2016). Moreover, the few studies available have used different outcomes for adolescents and for older people (Stafford et al., 2016), and they generally do not use a parenting styles approach, that needs to ensure first the orthogonality between the warmth and strictness dimensions (Stafford et al., 2015; Stafford et al., 2016). Furthermore, these studies do not ensure the comparability between samples from different generations (García, Gracia, & Zeleznova, 2013; García, Musitu, Riquelme, & Riquelme, 2011; Martínez, Cruise, García, & Murgui, 2017; Rothrauff et al., 2009; Stafford et al., 2015; Stafford et al., 2016), or between men and women (Martínez & García, 2007, 2008) through proper invariance analysis. Thus, in this study before examining the relationships between the four parenting styles and short- and long-term socialization outcomes (self-esteem and internalization of values) among adolescents and older adults, we will (1) examine the underlying orthogonality between the dimensions of warmth and strictness, as this is a core assumption to ensure the internal validity of the two-dimensional, four-style parenting models: authoritative, indulgent, authoritarian, and neglectful; and (2) we will conduct confirmatory factor analyses (CFA), to examine the factorial invariance of the warmth and strictness dimensions across age and gender groups. After the comparability across age and gender groups is ensured we aim to ascertain which parenting style is associated with better short- and long-term outcomes. Based on the above literature review we expect that high levels of parental warmth (present in both the authoritative and indulgent parenting styles) will be associated with better socialization outcomes (self-esteem and internalization of values) both in the short- (among adolescents) and long-term (among older adults).

Method

Participants

Participants were a sample of high school adolescent students (aged 12 to 17 years old) and a sample of older adults recruited from senior citizen centers (aged 60 to 75 years old) from a large metropolitan area in Spain with about one million inhabitants. A random selection of high schools and senior citizen centers was conducted from the complete list of high schools and senior citizen centers. If a school or senior citizen center declined to participate, another school or senior citizen center was randomly selected until completing the sample. This random sampling approach assures that every unit in the population (i.e., adolescents from high schools, and older adults from senior citizen centers) has the same probability of being selected (see Calafat et al., 2014; Fuentes, García, Gracia, & Lila, 2011; García & Gracia, 2010; Martínez, Fuentes, García, & Madrid, 2013). An a priori power analysis determined a minimum sample size of 1,104 observations to detect a power of .95 (α = .050, 1-β = .95) for a small-medium effect size (f = 0.125; estimated from ANOVAs of Lamborn et al., 1991) in a univariate F-test among four parenting style groups (Calafat et al., 2014; García & Gracia, 2009; Gracia, García, & Musitu, 1995; Pérez, Navarro, & Llobell, 1999).

The research protocol was approved by the research ethics committee of the Program for the Promotion of Scientific Research, Technological Development, and Innovation of the Valencian Community, which supported this research. To obtain the planned sample size, we contacted the directors of high schools and senior citizen centers, and they were invited to participate in the investigation (only a director of one senior citizen center chose not to participate). We required parental consent for adolescent participants and personal consent for older adult participants. Anonymity of responses was guaranteed for all participants. All participants in this study (96% response rate): (1) were Spanish, as were their parents and the four grandparents, (2) were adolescent students aged 12 to 17 years old or older adults aged 60 to 75 years old, (3) had received their parents’ approval if they were underage (i.e., adolescent participants), and (4) attended the designated classroom or room where the research was conducted. At the end of the sampling process, there were 1,098 participants, 571 adolescents, 323 girls (56.6%) and 248 boys from 7th through 12th grades and ranging in age from 12 to 17 (M = 15.14, SD = 1.9 years), and 527 older adults, 313 females (59.4%) and 214 males, ranging in age from 60 to 75 (M = 66.05, SD = 4.5 years).

Measures

Parenting styles. Warmth was measured using 13 items from the Warmth/Affection Scale for mothers (or primary female caregivers) (WAS; Ali, Khaleque, & Rohner, 2015). The WAS measures the extent to which adolescents perceive their mothers as loving, responsive, and involved (e.g., “Lets me know she loves me” and “Makes me feel proud when I do well”). For the older adults’ sample, items were adapted to measure to what degree they had perceived their mothers as loving, responsive, and involved during their adolescence (e.g., “Let me know that she loved me” and “Made me feel proud when I was doing well”). Cronbach’s alpha value for this scale was .935. Strictness was measured using 6 items from the Parental Control Scale for mothers (or primary female caregivers) (PCS; Calafat et al., 2014; García & Gracia, 2009; Rohner & Khaleque, 2003). The PCS measures the extent to which the adolescents perceive strict maternal control over their behavior (e.g., “Is always telling me how I should behave” and “Likes to tell me what to do all the time”). For the older adults’ sample, items were adapted again to measure to what degree they had perceived strict maternal control during their adolescence (e.g., “Was always telling me how to behave” and “Liked to tell me what to do all the time”). Cronbach’s alpha value for this scale was .859. On both parenting scales, adolescents and older adults rated all the items with the same 4-point scale (1 = almost never true, 4 = almost always true).

Four parenting styles (authoritative, indulgent, authoritarian, and neglectful) were defined by dichotomizing the sample on parental warmth and parental strictness and examining the two parenting variables simultaneously (Steinberg et al., 1994). Authoritative families were those who scored above the 50th percentile on both warmth and strictness, whereas neglectful families scored below the 50th percentile on both variables. Authoritarian families scored above the 50th percentile on strictness, but below the 50th percentile on warmth. Indulgent families scored above the 50th percentile on warmth, but below the 50th percentile on strictness.

Self-esteem. Self-esteem was measured with the multidimensional Self-concept Questionnaire Form 5 (AF5; García & Musitu, 1999) and with the Rosenberg’s (1965) Self-esteem Scale. The AF5 was designed to measure five self-esteem dimensions: academic (e.g., “I am a hard worker [good student]”), social (e.g., “I make friends easily”), emotional (e.g., reverse scored, “I am afraid of some things”), family (e.g., reverse scored, “I receive a lot of criticism at home”), and physical (e.g., “I take good care of my physical health”). The 30 items are answered on a 99-point scale, ranging from 1 = complete disagreement, to 99 = complete agreement. Both exploratory (García & Musitu, 1999) and confirmatory (García et al., 2013; García et al., 2011; Murgui, García, García, & García, 2012) factorial analyses confirmed the factor structure of the AF5 scales. Full factorial invariance across sex and age was confirmed, and no method effects were associated with negatively worded items (García et al., 2011). The AF5 has been validated in several languages (e.g., the English version, García et al., 2013), and the AF5 scales have been used in numerous studies to analyze self-esteem and other related constructs (e.g., Fuentes et al., 2011). Cronbach’s alphas for the AF5 subscales were: academic, .856, social, .754, emotional, .744, family, .786, and physical, .787. The scale by Rosenberg (1965) is a self-report measure of global self-esteem. It consists of 10 statements related to overall feelings of self-worth or self-acceptance (e.g., ‘I feel that I have a number of good qualities’). Items were measured on a 4-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha value for this scale was .841.

Internalization of social values. Self-transcendence and conservation values were measured with 27 items from the Schwartz (1992) Value Inventory (Martínez & García, 2007, 2008; Sortheix & Schwartz, 2017). Self-transcendence values included universalism (e.g., “wisdom [a mature understanding of life]”) and benevolence (e.g., “helpful [working for the welfare of others]”), and conservation values included tradition (e.g., “respect for tradition [protection of customs instituted for a long time]”), conformity (e.g., “respectful [showing consideration and honor]”), and security (e.g., “family security [taking care of loved ones]”). Participants rated all items with a 99-point rating scale coded from 1 (opposed to my values) to 99 (of supreme importance). Modifications were made to obtain a score index ranging from .1 to 9.99. Cronbach’s alphas for the subscales were: universalism, .822; benevolence, .750; security, .579; conformity, .710; and tradition, .563. These reliability indices were within the range of variation commonly observed for these value types (e.g., Martínez & García, 2007, 2008; Sortheix & Schwartz, 2017).

Plan of Analysis

We first compared the fit of the two-dimensional orthogonal theoretical model of socialization with two alternative models. First, we tested a one-factor model. This model represented a view of parenting as a one-dimensional construct. Second, we tested the correlated two-factor model. This model specified parenting as a two-dimensional construct where parental warmth and parental strictness are correlated. Third, we tested the theoretical orthogonal two-dimensional model. This model specified parenting as a two-dimensional construct, but as orthogonal (separate) dimensions that underlie parenting. These three alternative models were tested for both age groups (adolescents and older adults) and for both sexes (men and women). Finally, we compared four nested models for the age groups and sex samples. We conducted the following sequence of increasingly restrictive tests of invariance across samples: (a) unconstrained, without any restrictions across parameters, (b) factor pattern coefficients, (c) factor variances and covariances, and (d) equality of the error variances. Overall, chi-square tests of goodness-of-fit models are likely to be significant due to the oversensitivity of the chi-square statistic to the sample size (e.g., Bentler & Bonett, 1980; Cheung & Rensvold, 2002; García, Musitu, & Veiga, 2006). Therefore, other fit indexes were calculated: χ2/df, a score of 2.00-3.00 or lower is indicative of a good fit; root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA), values lower than .08 are considered acceptable; normed fit index and comparative fit index, NFI and CFI, whose values must exceed .90; and the information criterion of Akaike, AIC (Akaike information criterion), where the lowest value indicates the highest parsimony (Akaike, 1987) (see García et al., 2006; Gracia et al., 2018).

Finally, to analyze the influence of parenting styles on short- and long-term socialization outcomes, a three-way multifactorial (4 × 2 × 2) multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was applied to two sets of outcome variables (self-esteem and internalization of values) with parenting styles (authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful), age groups (adolescents vs. older adults), and sex (men vs. women) as independent variables. Follow-up univariate F tests were conducted for the outcome variables that had multivariate significant overall differences, and significant results on the univariate tests were followed up with Bonferroni comparisons of all possible pairs of means.

Results

Invariance across Age and Sex Groups

Fit indexes for the three alternative parenting models across age groups and sex are reported in Table 1. First, we constrained the data to test their consistency with the one-dimensional model. The results indicated that the statistics failed to meet the conventional standards, showing a poor fit (12-17 years old, RMSEA = .10, CFI = .88, AIC = 691; 60-75 years old, RMSEA = .11, CFI = .87, AIC = 802; men, RMSEA = .10, CFI = .86, AIC = 584; women, RMSEA = .10, CFI = .89, AIC = 768). Second, we constrained the data to test their consistency with the two-dimensional oblique model, obtaining a considerably better fit compared to the one-factor model (12-17 years old, RMSEA = .05, CFI = .97, AIC = 78; 60-75 years old, RMSEA = .05, CFI = .97, AIC = 33; men, RMSEA = .05, CFI = .97, AIC = 26; women, RMSEA = .04, CFI = .98, AIC = 32). Finally, we constrained the data to test their consistency with the theoretical parsimoniously orthogonal model, which did not yield an improved fit compared to the oblique model (12-17 years old, RMSEA = .05, CFI = .97, AIC = 81; 60-75 years old, RMSEA = .05, CFI = .97, AIC = 35; men, RMSEA = .05, CFI = .97, AIC = 25; women, RMSEA = .05, CFI = .98, AIC = 41). Overall, the results of the fit indexes across age and sex groups indicated that the theoretical orthogonal model was supported and resulted in an equal (oblique model) or better fit (one-factor) than the alternative models (one-factor and oblique model).

Table 1 Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Multi-sample Analysis of Invariance across Age and Sex

Note. Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square tests statistically significant (p <.01); df = degrees of freedom; RMSEA = root mean squared error of approximation; CFI = comparative fit index; AIC = Akaike information criterion (computed as χ2–2df).

Multi-group confirmatory factor analyses of invariance across age and sex groups are reported at the end of Table 1. The unconstrained parsimoniously orthogonal model indicated a good fit, suggesting a common factor structure across age groups and sex samples. Constraining the measurement weights yielded non-significant changes in fit across age groups, |ΔCFI| < .01, RMSEA = .038 overlaps with the previous 95% CI = .035-.042, and sex, |ΔCFI| < .01, RMSEA = .037 overlaps with the previous 95% CI = .034-.041, suggesting the invariance of the measurement weights across age groups and sex. Constraining structural covariances resulted in no changes in goodness-of-fit across age groups, |ΔCFI| < .01, RMSEA = .038 overlaps with the previous 95% CI = .035-.041, and sex, |ΔCFI| < .01, RMSEA = .037 overlaps with the previous 95% CI = .034-.041, indicating that structural covariances were invariant across age and sex groups. Constraining the error variances produced no significant changes in fit, |ΔCFI| < .01, RMSEA = .037 overlaps with the previous 95% CI = .035-.041, and sex, |ΔCFI| < .01, RMSEA = .037 overlaps with the previous 95% CI = .033-.040, suggesting no differences in error variances across age groups and sex. Overall, results of invariance tests across age and sex groups show that the theoretical orthogonal model operates in a similar way for adolescents and older adults, as well as for men and women.

Parenting Styles and Parental Dimensions

Participants (571 adolescents and 527 older adults) were classified into one of four groups (authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, or neglectful) (Table 2). The authoritative group had 256 participants (23.3%), with high warmth, M = 49.20, SD = 2.26, and high strictness, M = 19.53, SD = 2.44; the indulgent group had 299 participants (27.2%), with high warmth, M = 49.15, SD = 2.30, but low strictness, M = 12.02, SD = 2.72; the authoritarian group had 297 participants (27.0%), with low warmth, M = 36.37, SD = 6.62, but high strictness, M = 19.99, SD = 2.59; and the neglectful group had 246 participants (22.4%), with low warmth, M = 36.41, SD = 7.77, and low strictness, M = 12.48, SD = 2.62. No interactions were found when crossing age groups with parenting styles, χ2(3) = 3.67, p = .299, or when crossing sex with parenting styles, χ2(3) = 3.22, p = .359. Additionally, the two parenting dimensions measures, warmth and strictness, were modestly correlated, r = -.114, R2 = .01 (1%), p < .01. Although the 95% CI (.172, .055) did not include zero, the 95% CI proportion of variance (0.03, 0.00) did include zero. Overall, these results show that the measures of warmth and strictness were orthogonal and had an independent sex distribution per age group.

Multifactorial Multivariate Analysis of Variance

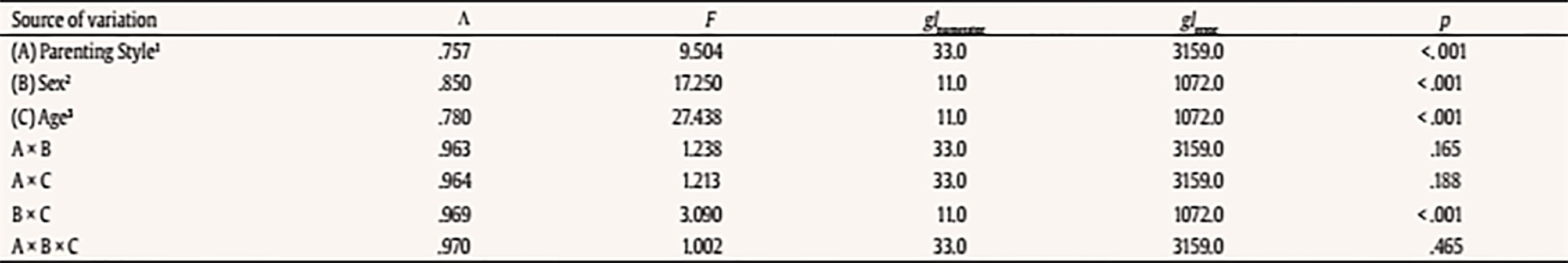

Main effects were found for parenting styles, Λ = .757, F(33.0, 3159.0) = 9.504, p < .001; sex, Λ = .850, F(11.0, 1072.0) = 17.250, p < .001; and age groups, Λ = .780, F(11.0, 1072.0) = 27.438, p < .001. Significant interaction effects were found for sex and age groups (Table 3), Λ = .969, F(11.0, 1072.0) = 3.090, p <.001.

Age and sex effects. With regard to measures of self-esteem (Table 4), adolescents scored higher on social and family self-esteem than older adults. Males also reported higher scores than females on emotional and global self-esteem. Interaction effects of sex and age were found on academic/professional self-esteem, F(1, 1082) = 6.68, p = .010, and physical self-esteem, F(1, 1082) = 7.84, p = .005 (Figure 1). On academic/professional self-esteem, older adults scored higher than adolescents, whereas only adolescent girls scored higher than adolescent boys. On physical self-esteem, although female scores were always the lowest, the decrease with age in males was greater than the decrease with age in females.

Table 4 Means and (Standard Deviations) of Parenting Style, Age Groups and Sex, and Main Univariate F Values for Outcomes Measures of Self-Esteem, and Internalization of Self-Transcendence and Conservation Values

Note. Bonferroni test α = .05;1 > 2 > 3 > 4.*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Figure 1 Means of Sex by Age for Academic/Professional Self-Esteem, Physical Self-Esteem, and Tradition Value.

Regarding the internalization of values, older adults reported the highest scores on benevolence, security, and conformity, and females had the highest scores on universalism, benevolence, security, and conformity. An interaction effect of sex and age was found on the tradition value, F(1, 1082) = 6.75, p = .010 (Figure 1). Older adults scored higher than adolescents, but only older female adults scored higher than older male adults.

Parenting styles and self-esteem. Adolescents and older adults with indulgent and authoritative parents reported higher academic/professional, physical, and global self-esteem than those from neglectful and authoritarian families (Table 4). Adolescents and older adults with indulgent parents reported greater social, emotional, and family self-esteem than their counterparts from authoritative, neglectful, and authoritarian families (see Table 4).

Parenting styles and internalization of values. Adolescents and older adults from indulgent and authoritative families gave higher priority to self-transcendence values (universalism and benevolence) and conservation values (security, conformity, and tradition) than those from authoritarian and neglectful homes, whereas those from neglectful and authoritarian families scored lower on all the internalization of values measures (see Table 4).

Discussion

This study analyzed the association between parenting styles and short- and long-term socialization outcomes using a two-dimensional four-typology model of parenting styles in a large sample of Spanish adolescents and older adults. The short- and long-term socialization outcomes analyzed were self-esteem (academic, social, emotional, family, physical, and global) and internalization of social values (self-transcendence and conservation values).

Regarding self-esteem, both adolescents and older adults from indulgent families reported equal or even higher self-esteem than those from authoritative households, whereas those from neglectful and authoritarian homes were consistently associated with the lowest levels of self-esteem. Regarding internalization of social values, adolescents and older adults raised in indulgent and authoritative families prioritized self-transcendence values (universalism and benevolence) and conservation values (security, conformity, and tradition) as compared to those from authoritarian and neglectful homes, whereas those from neglectful and authoritarian families showed lower scores on all internalization of social values measures. Thus, a main contribution of the present study, is to show that the link between parenting styles and socialization outcomes share a common short- and long- term pattern with respect to self-esteem and internalization of social values. Our results support the idea, suggested by earlier socialization researchers (e.g., Steinberg et al., 1994), that the benefits of an optimal parenting style are either maintained or increased over time (Rothrauff et al., 2009; Stafford et al., 2015; Stafford et al., 2016).

An important implication of this study is that the combination of high levels of parental warmth and involvement, and low levels of strictness and imposition (i.e., the indulgent parenting style) seems to be an optimum parenting strategy in the cultural context where the study was conducted, supporting previous research (Calafat et al., 2014; García & Gracia, 2009, 2010; Gracia et al., 2012; Martínez et al., 2019).

Results regarding the link between parenting styles that share high levels of warmth (i.e., indulgent and authoritative) and the internalization of social values have also interesting implications. The process of internalization of self-transcendence and conservation values involved socially-focused motivations that the findings of this study clearly associated with indulgent and authoritative parenting styles (Martínez & García, 2007, 2008; Sortheix & Schwartz, 2017), emphasizing the positive effects on others of fostering a child’s feelings of empathy and consideration for others (Baumrind, 1983; Hoffman, 1970; Lewis, 1981). However, authoritarian and neglectful parenting styles, both lacking the parenting component of warmth and involvement, appear to be linked with lack of empathy and no consideration for others’ feelings.

In contrast with research conducted in other cultural contexts, in the present study the indulgent parenting style was associated with the same level of self-esteem (academic/professional, physical, and global self-esteem) or even higher level of self-esteem (social, emotional, and family self-esteem) than the authoritative parenting style. This suggests that in the Spanish and other South European and Latin American countries (see García & Gracia, 2014, for a review) high strictness does not play a key role for optimal socialization outcomes, as it appears to be the case in other cultural contexts where a high level of strictness (shared by the authoritative and authoritarian parenting styles) has been associated with offspring’s adjustment and well-being (Clark et al., 2015; Darling & Steinberg, 1993; Deater-Deckard et., 1996; Furstenberg et al., 1999). For example, in contexts where the authoritative parenting style has been found to be optimal, high levels of strictness is as important as high levels of parental warmth to foster optimal socialization outcomes (Baumrind, 1971, 1983; Darling & Steinberg, 1993; Lamborn et al., 1991; Maccoby & Martin, 1983; Steinberg et al., 1994). The importance of the warmth dimension in our study has also implications for psychosocial interventions addressing parenting, as it is in line with family intervention programs highlighting the importance of positive parenting (e.g., Álvarez, Padilla, & Máiquez, 2016; Hidalgo, Jiménez, López-Verdugo, Lorence, & Sánchez, 2016; Martínez-González, Rodríguez-Ruiz, Álvarez-Blanco, & Becedóniz-Vázquez, 2016; Pedro, Altafim, & Linhares, 2017; Suárez, Rodríguez, & Rodrigo, 2016).

This paper also addressed important methodological gaps in the literature examining the link between parenting styles and short- and long-term socialization outcomes. Unlike previous studies (e.g., Martínez & García, 2007, 2008; Rothrauff et al., 2009; Stafford et al., 2015; Stafford et al., 2016), this study used multi-sample confirmatory factor analysis to ensure that the parenting style measures used were invariant across age groups (adolescents and older adults) and across men and women. In the present study, for both age and sex groups, the items underlie the same dimensions and had the same relative importance in the assigned factor for the four samples (i.e., adolescents, older adults, men, and women). Additionally, the two factors have an equivalent structure of variances and an equivalent relational pattern of covariances. Finally, results confirmed the strict assumption of equal error variances among the four samples for all the items of the questionnaire (e.g., García et al., 2013; García et al., 2011; Gracia et al., 2018). Also, and in contrast with previous research, our findings confirm the orthogonality of the two parenting dimensions: warmth and strictness (Kerr & Stattin, 2000; Martínez & García, 2007, 2008; Martínez et al., 2017, 2019; Stattin & Kerr, 2000; Steinberg et al., 1994). The results of the confirmatory factor analysis confirmed that the orthogonal two-factor model provided a superior fit to the data. In this regard, our results provided full support for the internal validity of the two-dimensional and four-style parenting model (see Lamborn et al., 1991).

Finally, this study has strengths and limitations. The use of the two-dimensional four-style model to assess parenting offers an approach to the ongoing debates by examining parenting styles in an ample context of different outcomes across different demographic variables, cultural contexts, and countries. Additionally, we tested the structural variance of the warmth and strictness measures of parenting across adolescence and late adulthood and in both sexes. As for the limitations, the current study was cross-sectional, which does not allow us to draw firm conclusions about directionality. However, we believe that the results obtained regarding the short- and long-term association between parenting styles, self-esteem, and social values advance the current knowledge in this field of study and provide insights to orientate parental education programs that aim to improve relationships with children and enhance their resources and quality of life.