Introduction

Child-to-parent violence (CPV) is defined as any act performed by a child towards his/her parents with the intention of causing physical, psychological, emotional, or financial damage or losing and gaining power and control over them (Cottrell, 2003; Martínez Pastor, 2017; Stewart, Wilkes, Jackson, & Mannix, 2006). This type of violence is shaped mainly by two dimensions: physical violence (e.g., pushing, hitting, slapping) and psychological violence (e.g., insulting, shouting, intimidating) (Beckmann, Bergmann, Fischer, & Mößle, 2017; Lyons, Bell, Fréchette, & Romano, 2015).

Most studies have focused on family processes such as family communication (Cava, Buelga, & Musitu, 2014), family functioning (Ortega-Barón, Buelga, & Cava, 2016) and, in particular, parenting styles (Gámez-Guadix & Calvete, 2012; Ibabe & Bentler, 2016; Ibabe & Jaureguizar, 2011; Moral-Arroyo, Martínez-Ferrer, Suárez-Relinque, Ávila-Guerrero, & Vera-Jiménez, 2015). Parenting styles refer to forms or educational strategies that parents use to build values, beliefs, attitudes, and norms of behavior appropriate to the society in which their children live (Estévez, Jiménez, & Cava, 2016; Fuentes, García, Gracia, & Alarcon, 2015).

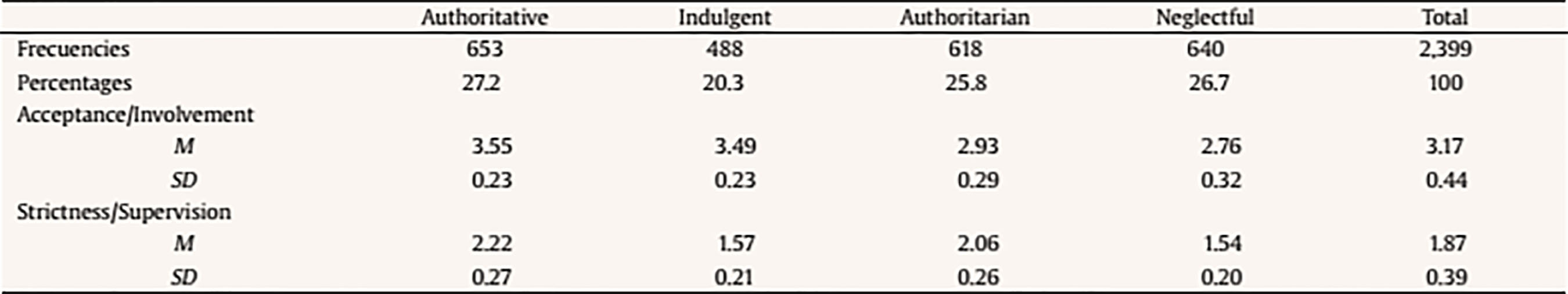

In the present study, Musitu and García’s typologies of parenting styles are used, based on two orthogonal dimensions: demandingness and responsiveness (Musitu & García, 2001). Demandingness refers to the extent to which parents supervise and take control; responsiveness refers to the extent to which parents show their children warmth and acceptance, give them support, and use reasoning in their parent-child relationships (Martínez & García, 2007). Most research has labelled these dimensions as involvement/acceptance and strictness/supervision. Based on these axes, four parenting styles are represented: authoritarian (high strictness/supervision and low acceptance/involvement), authoritative (high strictness/supervision and acceptance/involvement), indulgent (low strictness/supervision and high acceptance/involvement), and neglectful (low strictness/supervision and low acceptance/involvement).

Regarding the relationships between parenting styles and CPV, it has been observed in some studies that the authoritarian style is closely related to CPV, probably because parents exercise a high degree of control over their children and can even reach the point of using physical punishment (Gámez-Guadix, Almendros, Carrobles, & Muñoz, 2012; Sánchez-Meca et al. 2016). However, in other studies it has been pointed out that the neglectful style is also related to a higher CPV, due to the lack of control and supervision, and also of affection (Cerezo & Ato, 2010; Gámez-Guadix, Jaureguizar, Almendros, & Carrobles, 2012; Suárez, Rodríguez, & Rodrigo, 2016). These differences have been attributed to cultural factors (Ibabe & Bentler, 2016) and structural factors, such as sex and age (Musitu & García, 2001).

Also, it has been found that CPV is associated with variables of psychosocial adjustment (Calvete, Orue, Gámez-Guadix, del Hoyo-Bilbao, & de Arroyabe, 2015; Moral-Arroyo, Varela-Garay, Suárez-Relinque, & Musitu, 2015; Sanchez-Meca et al., 2016). However, there are few studies in which the role of parenting styles is taken into account in these dimensions. In the present study, the relationships between CPV and parental socialization styles with psychosocial adjustment indicators such as alexithymia, problematic use of social networking sites (PUSNS) and attitude towards institutional authority are examined.

The term alexithymia is used to describe disturbance in affect regulation characterized by a difficulty in identifying and verbalizing differentiated feelings, a way of thinking which focuses primarily on the actual aspects of external circumstances rather than subjective experiences and by a limited fantasy life (Kooiman et al., 2004). It has been found that alexithymia plays an important role in the links between inadequate parenting and adjustment problems (Taylor & Bagby, 2012; Van der Velde et al., 2013), such as the expression of violent behavior (Wachs & Wright, 2018) and, in particular, dating violence (Moral de la Rubia & Ramos-Basurto, 2015), cyberbullying and cybervictimization (Aricak & Ozbay, 2016), and CPV (Lozano-Martínez, Estévez, & Carballo-Crespo, 2013). However, there are few studies in which implications of parenting styles in alexithymia, especially in community samples, are examined. In this area, it has been pointed out that the degree of alexithymia was negatively associated with the degree to which positive feelings were expressed in the family (Kench & Irwin, 2000) and positively associated with a general measure of pathological family interactions (Lumley, Mader, Gramzow, & Papineau, 1996). In this sense, lack of affection by both parents is associated with the degree of alexithymia (Taylor, Bagby, & Parker, 1999). It seems reasonable to assume that alexithymia is not only associated with inadequate parenting styles, but also with CPV.

One of the dimensions that have been studied in the present work is PUSNS, defined as an excessive concern with connecting to these interaction spaces dedicating such a large amount of time that other areas such as social activities, studies/work, interpersonal relationships, psychological health, and well-being are affected (Andreassen & Pallesen, 2014). PUSNS usually affects populations who are vulnerable because of their age, such as adolescents (Pallanti, Bernardi, & Quercioli, 2006; Puerta-Cortes & Carbonell, 2014). This high level usage of social networking sites can be attributed to the fact that these virtual spaces constitute a scenario away from the supervision of parents or other figures of formal authority (Andreassen, 2015; Mazzoni & Iannone, 2014).

A growing body of research also supports the relationship of PUSNS with psychosocial adjustment indicators such as depression (Özdemir, Kuzucu, & Ak, 2014), loneliness (Caplan, 2007; Gámez-Guadix, Villa-George, & Calvete, 2012), self-control (Caplan, 2010; Montag, Jurkiewicz, & Reuter, 2010), and alexithymia (Schimmenti et al., 2017). Also, it has been related to anger, hostility, and impulsivity (Aymerich, Musitu, & Palmero, 2018; Balkan & Adalier, 2011; Carli et al., 2012; Echeburúa et al., 2009), peer violence (Martínez-Ferrer, Moreno, & Musitu, 2018; Martínez-Ferrer & Moreno-Ruiz, 2017), bullying (Arnaiz, Cerezo, Giménez, & Maquiló, 2016), cyberbullying (Giménez-Gualdo, Maquilón-Sánchez, & Arnaiz- Sánchez, 2015), cybervictimization, and dating violence (Blanco Ruiz, 2014; Martín Montilla, Pazos Gómez, Montilla Coronado, & Romero Oliva, 2016). However, so far, no research has analyzed the association between PUSNS and CPV.

On the other hand, parenting styles have also a significant effect on children’s use of the Internet and social networking sites (Özgür, 2016; Valcke, Schellens, Van Keer, & Gerarts, 2007). The Internet is a medium over which parents often have very little control, few rules for use, with minimal parental supervision, mostly due to their own lack of knowledge of the Internet. In fact, many online activities are carried out alone, in an anonymous context (Leung & Lee, 2012). One of the main effects of PUSNS in the family is the isolation of adolescents from their family and social environment, which is expressed by a decrease in communication with family members and a reduction of their social circle. However, regarding relations with parenting styles, the results are inconclusive. Research suggests that parenting styles characterized by high strictness/supervision (authoritative and authoritarian) decrease the likelihood of being addicted to the Internet (Cheung, Yue, & Wong, 2015; Mesch, 2009). However, styles characterized by high involvement/acceptance, which often use parental mediation, do not seem to be related to the problematic use of Internet and social networking sites in adolescence (Leung & Lee, 2012).

Another dimension scarcely explored in the field of CPV is the attitude toward institutional authority. However, recent studies have indicated that adolescents’ attitude towards authority figures, such as teachers and parents, is related to the involvement in violent behavior among peers (Abiétar-López, Navas-Saurin, Marhuenda-Fluixá, & Salvà-Mut, 2017; Musitu, Estévez, & Emler, 2007; Romero-Abrio, Martinez-Ferrer, Sanchez-Sosa, & Musitu, in press; Varela-Garay, Ávila, & Martínez- Ferrer, 2013), with cyberbullying (Carrascosa, Cava, & Buelga, 2015) and with delinquency (Estévez, Emler, Cava, & Inglés, 2014; Tarry & Emler, 2007). However, no research has explored the relationship betweeen CPV and attitude towards authority, despite the fact that parents represent the main figures of informal authority for the adolescent.

Finally, in relation to CPV and gender, this type of violence is predominant in boys (Aroca-Montolío, Lorenzo-Moledo, & Miró-Pérez, 2014). However, when the type of violent behavior is considered, boys use physical violence to a greater extent towards their parents, while girls engage in psychological, verbal, or emotional violence (Gámez Guadix et al., 2012; Martínez Pastor, 2017; Rico, Rosado, & Cantón-Cortés, 2017). Regarding, alexithymia, boys are likely to show more difficulties in identifying and interpreting emotions (Levant, Hall, Williams, & Hasan, 2009). As for gender differences in PUSNS, this is still little explored. Some studies have shown that girls use social networking sites more than boys (Andreassen, 2015; Griffiths, Kuss, & Demetrovics, 2014; Ryan, Chester, Reece, & Xenos, 2014), whereas boys tend to spend more time than girls playing video games or visiting web pages (Watters, Keefer, Kloosterman, Summerfeldt, & Parker, 2013).

Drawing from the above, the main objective of the present study is to analyze the relationships between CPV and parenting styles and examining their link with the following psychosocial adjustment indicators: alexithymia, PUSNS, and attitude towards institutional authority. It is expected that:

H1: Alexithymia, PUSNS, and attitude towards institutional authority are related to higher CPV.

H2: Indulgent and authoritative parent styles are related to lower CPV as compared to neglectful and authoritarian styles.

H3: Relationships between CPV, parenting styles, alexithymia, PUSNS, and attitude towards institutional authority will be different for boys and girls.

Method

Participants

The population of reference for this study consisted of secondary and high school students of western Andalusia (Spain), constituted by the provinces of Huelva, Sevilla, Cádiz, and Córdoba. The selection of the participants was carried out via a stratified randomized cluster sampling. The sampling units were: geographical area (province) and school (public and semi-public secondary and high schools). The sample size – with a sampling error of ± 2%, a confidence level of 95%, and p = q = .50 – was estimated at 2,399 students (50.2% boys and 49.8% girls) aged 12 to 18 years (M = 14.63, SD = 1.91), from 19 schools, of which 12 are state owned and 7 are private/subsidized. The analysis of mean differences based on the location of the school and its public or private status in the study’s target variables were not significant and, therefore, these variables were not included in the subsequent analyses. Missing values were handled using the regression imputation method (Graham, 2009). Following the criteria provided by Hair, Hult, Ringle, and Sarstedt (2016), atypical values were those whose standardized scores had an absolute value above 4. For multivariate detection, Mahalanobis distance was computed. A multivariate outlier is identified if the associated probability at a Mahalanobis distance is 0.001 or less (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007).

Instruments

Problematic Use of Social Networking Sites Scale (Martínez-Ferrer et al., 2018). It consists of 13 items that, with a response range of 1 (never) to 4 (always), measures the problematic use of SNS (e.g., “I need to be connected to my social networks continuously”). Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .84.

Child-to-Parent Violence Scale. The Spanish adaptation of the Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2, children to parents version) was used (Straus & Douglas, 2004, adapted by Gámez-Guadix, Straus, Carrobles, Muñoz-Rivas, & Almendros, 2010). This Likert-type scale consists of two subscales of 6 items, violence towards the mother and violence towards the father (e.g., “I hit or have hit my parents with something that could hurt them”), with 7 response options (0 = never, 6 = more than 20 times). The scale offers a global index of CPV and scores on two factors: physical violence and verbal violence. Cronbach’s alpha for the full scale was .71., for the subscale of violence toward the mother it was .70, and .75 (physical violence) and .71 (verbal violence) and for the subscale of violence toward the father it was .75, and .85 (physical violence) and .70 (verbal violence).

Parenting Styles Scale (ESPA29; Musitu & García, 2001). The scale consisted of 29 relevant situations in children’s daily life and possible parental responses. These assessments allow for obtaining general measures of acceptance/implication and severity/imposition of father and mother (e.g., “If I obey the things she/he sends me...”). Based on the scores on both axes – acceptance/involvement and strictness/imposition – families were classified into four types of parenting styles: authoritative, indulgent, authoritarian, and neglectful. The consistency for the global scale was .97. In the factors separated by mother and by father, the internal consistency was as follows: affection .94 for both, indifference .92 for both, dialogue .93 for both, apathy .84 and .82 respectively, verbal coercion 0.90 for both, physical coercion .90 and .91 respectively, and deprivation .91 and .92 respectively. The factorial structure of the scale has been confirmed in several cross-cultural studies (Martínez, García, Musitu, & Yubero, 2012).

Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) (Bagby, Parker, & Taylor, 1994; adapted by Moral de la Rubia & Retamales, 2000). For this study we used the “difficulty in identifying and expressing emotions” factor. The internal consistency for this factor was .84.

Attitudes towards the Institutional Authority in Adolescents Scale (AAI-A) (Cava, Estévez, Buelga, & Musitu, 2013). It consists of 10 items, with four options for responses (1 = no agreement, 4 = total agreement) that measure two factors: positive attitude towards authority (e.g., “Teachers are fair when evaluating”) and positive attitude towards transgression of norms (e.g., “If you do not like a school rule, it’s best not to follow it”). Cronbach’s alpha was .90 and .92, respectively.

Procedure

First, we contacted the principals of the selected educational centres, explained the research project to them and asked for their agreement. After this initial contact, an informative seminar was addressed to teachers as well as members of the administration to explain the research objectives. Next, a letter describing the study was sent to parents, requesting them to indicate in writing whether they accepted their child’s participation in the study (only 1.5 % of the parents refused). Participants anonymously and voluntarily filled out the scales during regular classroom hours (45 min). Trained researchers administered the instruments to the adolescents during the school hours, assuring them that their participation in the study was voluntary and anonymous at all times. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki principles for research with human beings (World Medical Association. 2013).

Data Analysis

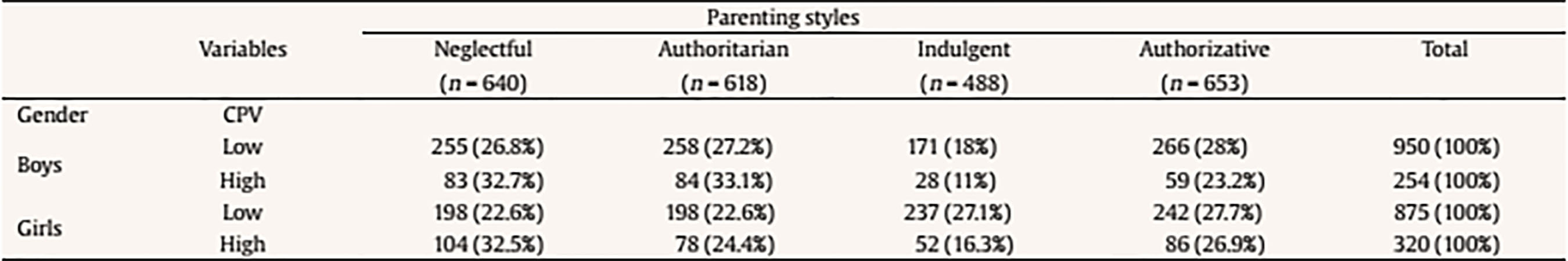

Firstly, a two-step cluster analysis was performed using the two CPV factors of father and mother (physical violence and verbal violence), in order to obtain the optimum number of clusters. Two clusters were obtained with a good fit: high and low CPV. Secondly, the k-means cluster analysis was carried out, a recommended procedure when the volume of data to be classified is large and the data categories are established a priori (Closas, Arriola, Kuc, Amarilla, & Jovanovich, 2013). Thirdly, a multivariate factorial design (MANOVA, 2 × 4× 2) was conducted with CPV (high and low), parenting styles (authoritative, indulgent, authoritarian, and neglectful), and gender (boy and girl) as fixed factors; and as dependent variables alexithymia (difficulty to identify and express emotions), attitudes towards authority (two factors) and PUSNS were used, to analyze possible interaction effects. The 25th SPSS edition was used.

Results

Descriptive Analysis

The distribution of adolescents according to parental styles, CPV, and gender can be seen in Table 1 and Table 2. The percentage of boys and girls was similar in the four parenting styles, depending on the CPV.

Multivariate Analysis

A MANOVA was carried out and significant differences were obtained in the main effects of CPV, Λ = .930, F(4, 1724) = 32.440, p <.001, η2p = .070; parenting styles, Λ = .961, F(12, 4561.567) = 5,770, p < .001, η2p = .013; and gender, Λ = .945, F(4, 1724) = 25.267, p < .001, η2p = .055. The effect size of η2p was between moderate and low.

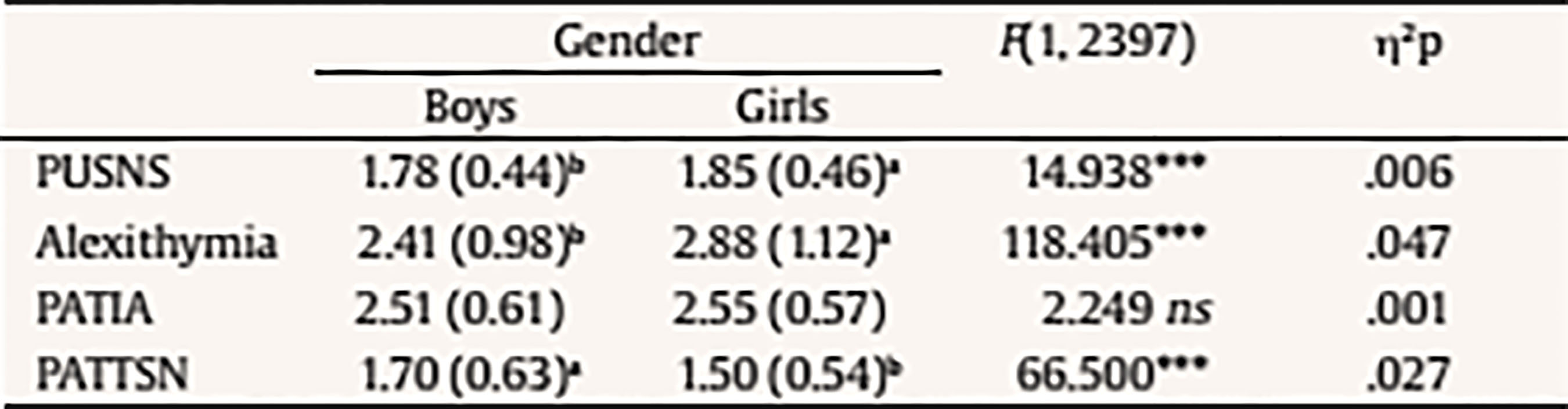

Regarding gender, ANOVA results showed significant differences in PUSNS, F(1, 2397) = 14.938, p <.001, η2p = .006; alexithymia, F(1, 2397) = 118.405, p <. 001, η2p = .047; and positive attitude towards the transgression of social norms, F(1, 2397) = 66.500, p <.001, η2p = .027. As shown in Table 3, girls scored higher than boys in PSUSNS and alexithymia, while girls scored higher in positive attitude toward transgression social norms.

Table 3 Means, Standard Deviation (SD), and ANOVA Results between Gender and PUSNS, Alexithymia, Positive Attitude towards Institutional Authority, and Positive Attitude towards Transgression of Social Norms

Note. α = .05; a > b; ns = non-significant; PUSNS = problematic use of social networking sites; CPV = child-to-parent violence; PATIA = positive attitude towards institutional authority; PATTSN = positive attitude towards transgression social norms. *p < .05, **p < .001.

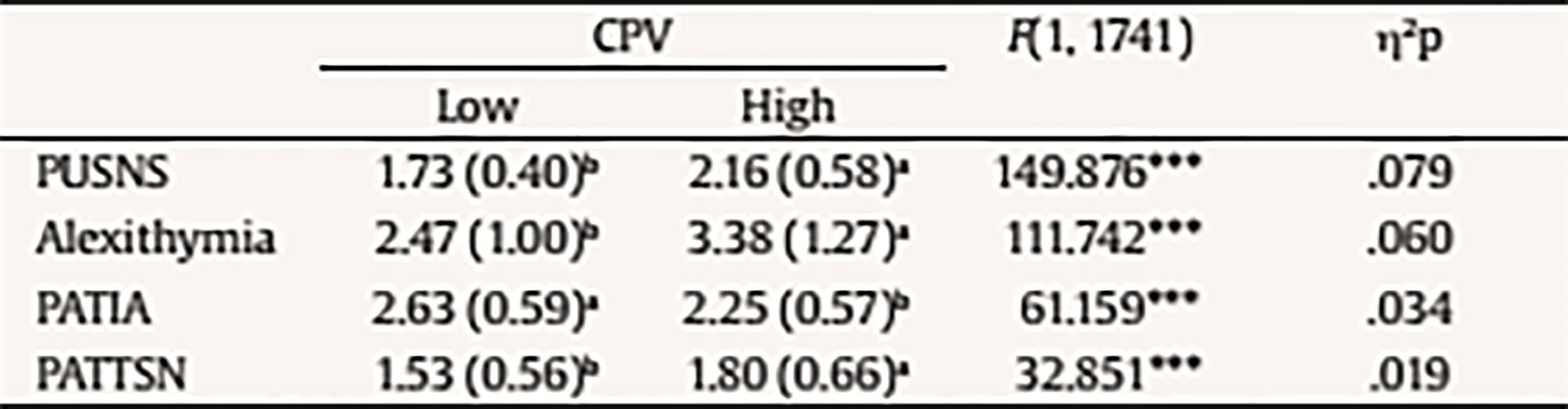

Regarding CPV, ANOVA results showed significant differences in PUSNS, F(1, 1741) = 149.876, p < .001, η2p = .079; alexithymia, F(1, 1741) = 111.742, p < . 001, η2p = .060; positive attitude toward institutional authority, F(1, 1741) = 61.159, p < .001, η2p = .034; and positive attitude towards the transgression of social norms, F(1, 1741) = 32.851, p < .001, η2p = .019 (see Table 4).

Table 4 Means, Standard Deviation (SD), and ANOVA Results between CPV and PUSNS, Alexithymia, Positive Attitude towards Institutional Authority, and Positive Attitude towards Transgression of Social Norms

Note. α = .05; a > b; PUSNS = problematic use of social networking sites; CPV = child-to-parent violence; PATIA = positive attitude towards institutional authority; PATTSN = positive attitude towards transgression social norms.*p < .05, ***p < .001.

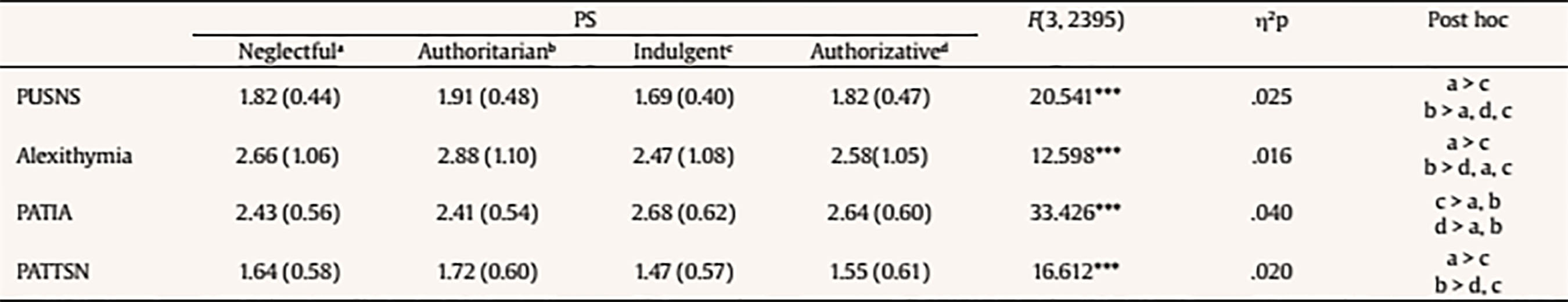

In the ANOVA regarding parenting styles, significant differences were obtained in PUSNS, F(3, 2395) = 20,541, p <.001, η2p = .025; alexithymia, F(3, 2395) = 12.598, p <.001, η2p = .016; positive attitude towards institutional authority, F(3, 2395) = 33,426, p <.001, η2p = .040; and positive attitude toward the transgression of social norms, F(3 , 2395) = 16.612, p <.001, η2p = .020. As shown in Table 5, the results obtained in the Bonferroni test (α = .05) showed that adolescents from families with an authoritarian style obtained the highest scores in PUSNS, alexithymia, and positive attitude towards the transgression of norms, whereas those with an indulgent parenting style obtained the highest scores in positive attitude toward authority. The effect size of η2p was low.

Table 5 Means, Standard Deviation (SD) and ANOVA Results between Parenting Styles and PUSNS, Alexithymia, Positive Attitude towards Institutional Authority, and Positive Attitude towards Transgression of Social Norms

Note. α = .05; a > b > c; ns = non significative; PS = parenting styles; PUSNS = problematic use of social networking sites; PATIA = positive attitude towards institutional authority; PATTSN = positive attitude towards transgression social norms. *p < .05, ***p < .001.

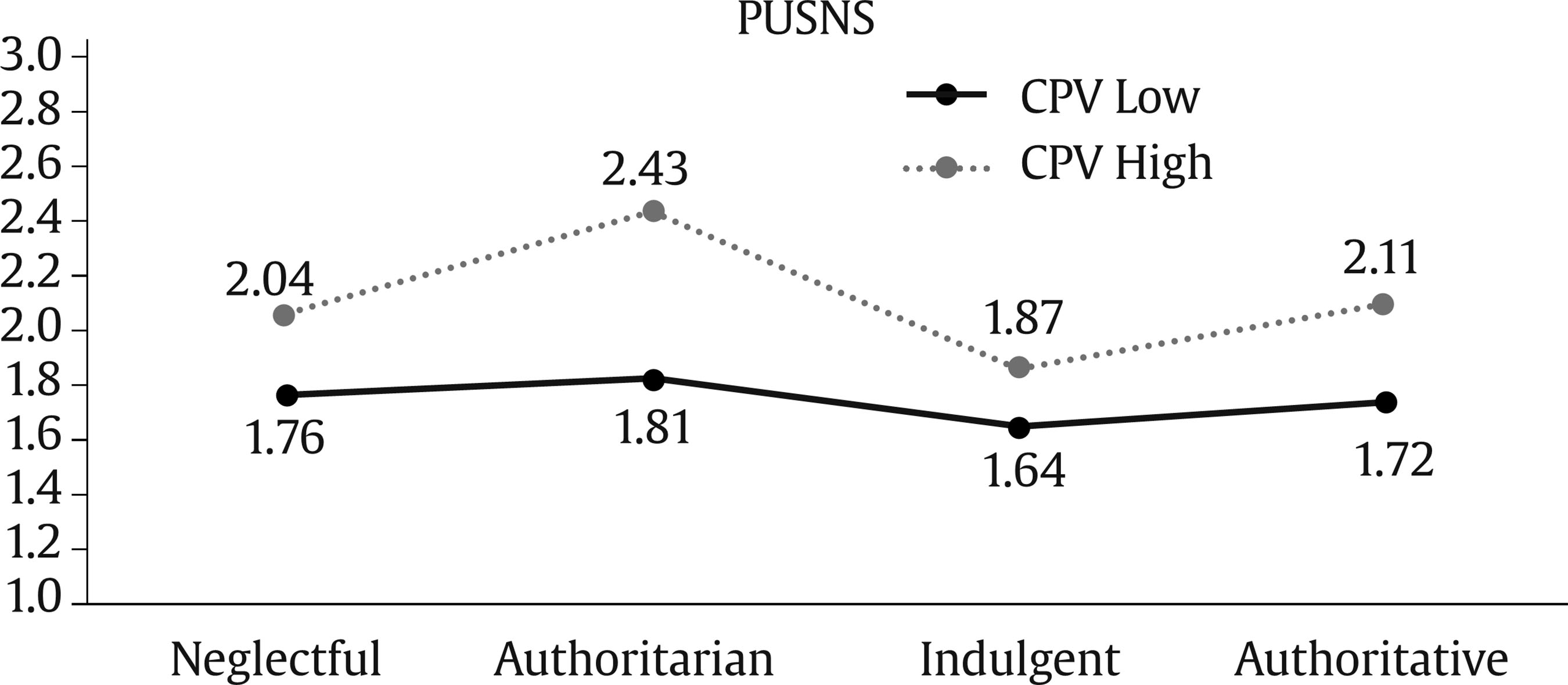

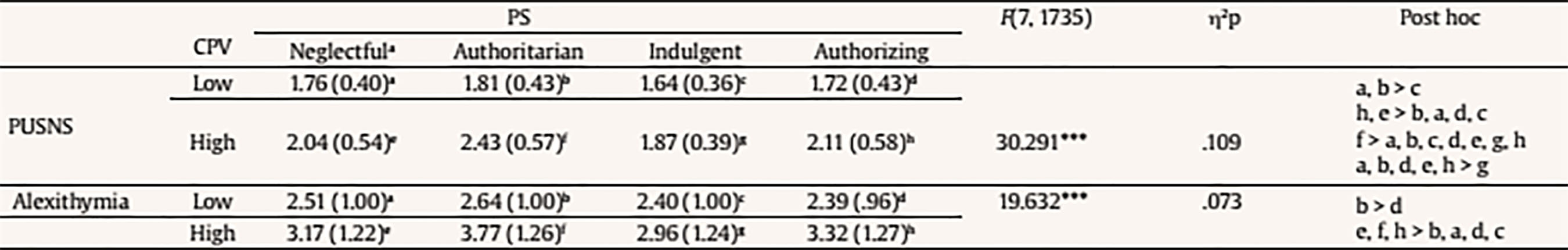

Univariate Analyses of Interaction Effects

Firstly, a statistically significant interaction effect was obtained between CPV, parenting styles, and PUSNS, F(7, 1735) = 30.291, p <.001, η2p = .109. The results of the post-hoc contrasts performed with the Bonferroni test (α = .05) (see Table 6 and Figure 1) indicated that adolescents from families with a predominant authoritarian style and high CPV showed the highest scores in PUSNS. In addition, neglectful and authoritative styles and styles high in CPV obtained higher scores in PUSNS than the four styles with low CPV. Finally, the indulgent style is the most functional, especially when the CPV is low. The effect size of η2p is moderate.

Table 6 Means, Standard Deviation (SD), and Results ANOVA between CPV, Parenting Styles, PUSNS, and Alexithymia

Note. α = .05; PS = parenting styles; PUSNS = problematic use of social networking sites; CPV = child-to-parent violence. ***p < .001.

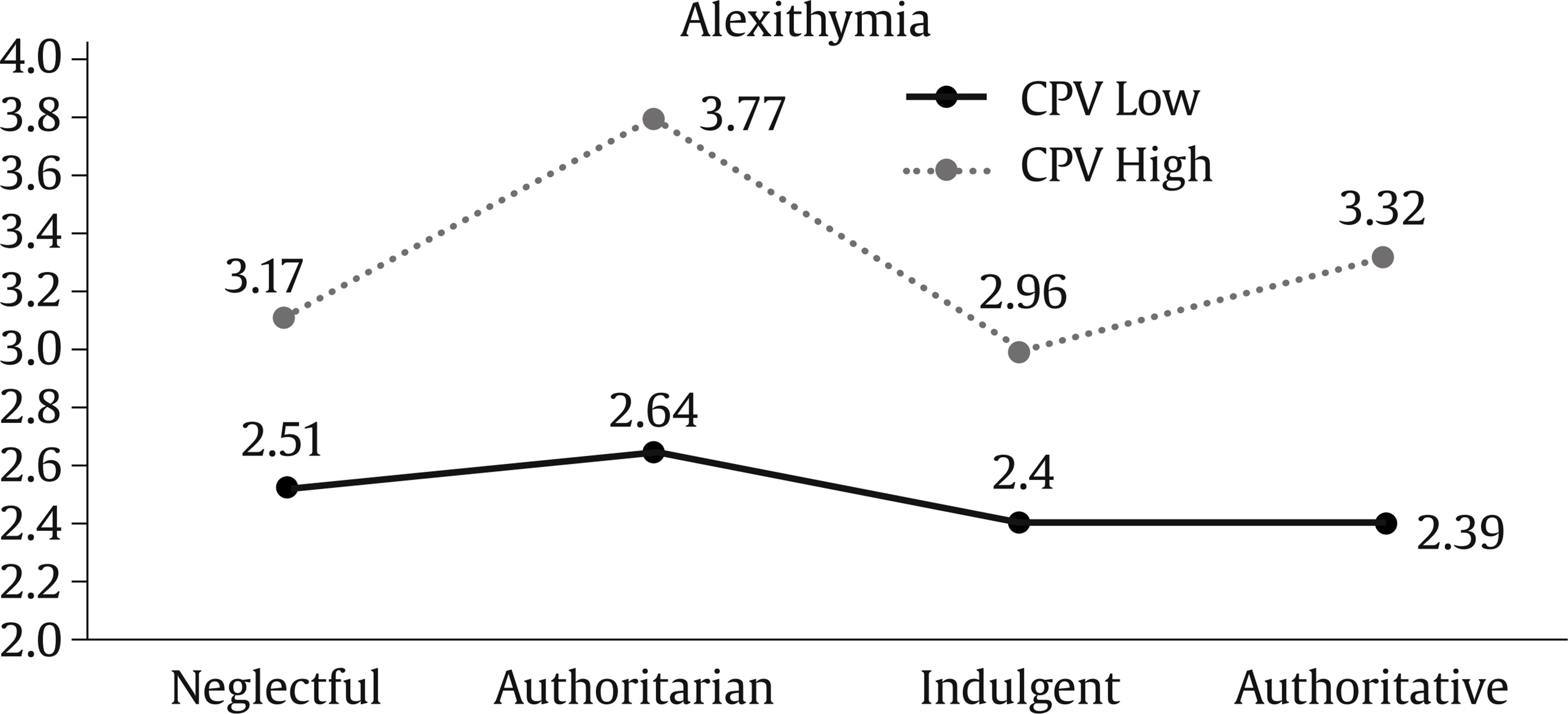

Secondly, a statistically significant interaction effect was obtained between CPV, parenting style and alexithymia, F(7, 1735) = 19.632, p <.001, η2p = .073. The results of post-hoc contrasts with Bonferroni test (α = .05) (see Table 6 and Figure 2) showed that when the CPV was high, the authoritarian, neglectful, and authoritative styles showed higher scores in alexithymia than the four styles with low CPV. Again, it was observed that the indulgent style was the most functional when CPV was low. The effect size of η2p was moderate.

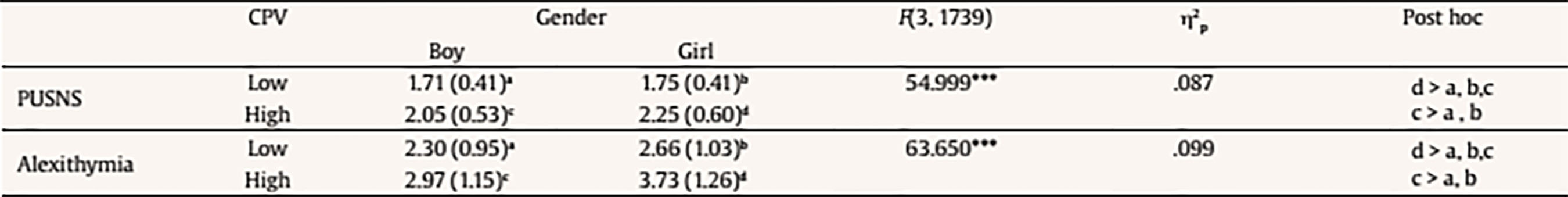

Thirdly, a statistically significant interaction effect between CPV, gender, and PUSNS was also obtained, F(3, 1739) = 54.999, p <.001, η2p = .087. As shown in the results (see Table 7 and Figure 3), when CPV was low, PUSNS was equivalent in boys and girls. However, when CPV was high, girls were the ones with the highest PUSNS. The effect size of η2p was moderate.

Table 7 Means, Standard Deviation (SD) and Results ANOVA between CPV, Gender, PUSNS, and Alexithymia

Note. α = .05; PUSNS = problematic use of social networking sites; CPV = child-to-parent violence. ***p < .001.

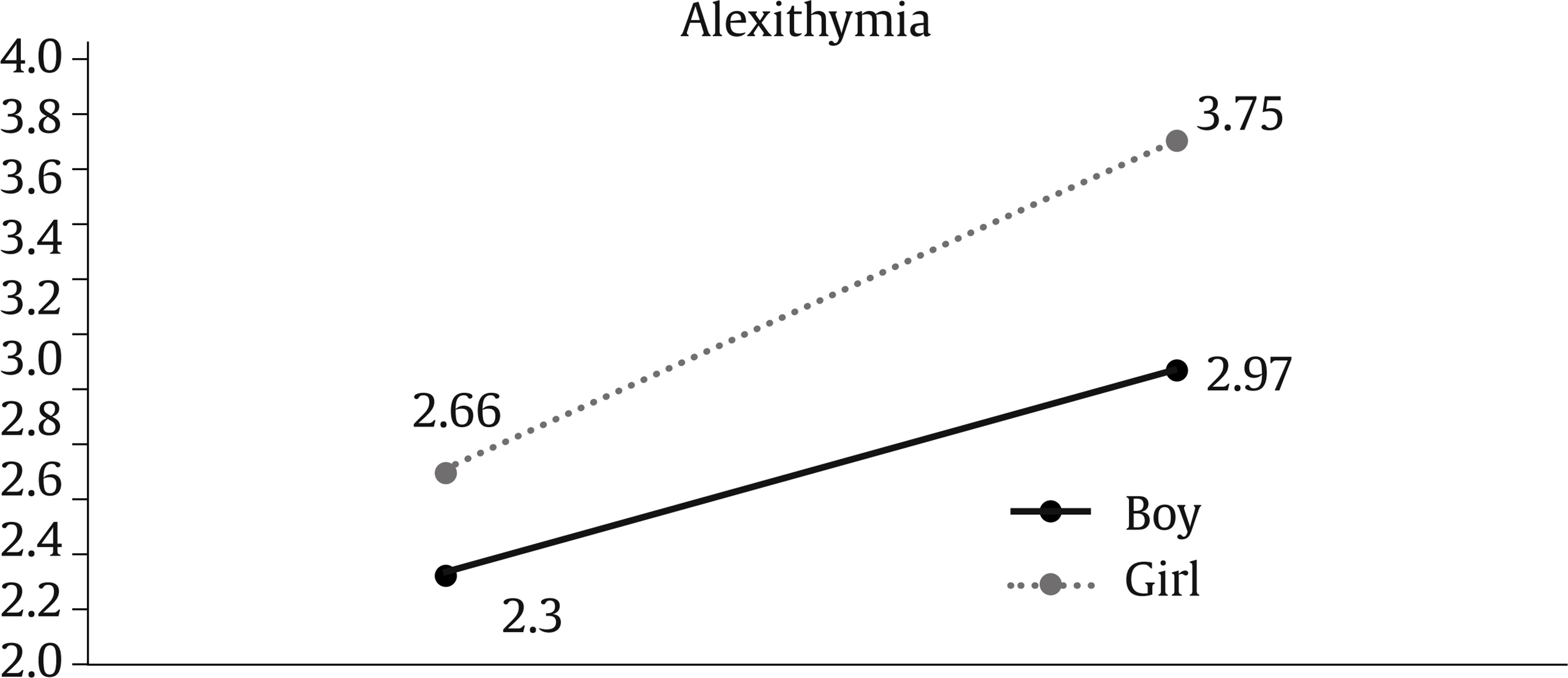

Finally, a statistically significant interaction effect was obtained between CPV, gender, and alexithymia, F(3, 1739) = 63,650, p <.001, η2p = .099 (see Table 7 and Figure 4). When CPV was high, the difficulty in identifying emotions in girls was greater than in boys with high and low CPV and in girls with low CPV. The effect size of η2p was moderate.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to analyze the relationships between CPV and parenting styles and their relationship with the following psychosocial adjustment indicators: alexithymia, PUSNS, and the attitude towards institutional authority. The results obtained show that CPV and parental socialization styles are significantly related to alexithymia, PUSNS, and attitude towards institutional authority.

Overall, the present findings confirm that adolescents with high CPV have a higher PUSNS, more difficulty in interpreting emotions, and a more positive attitude toward the transgression of social norms, supporting the first hypothesis. Our results now provide evidence that PUSNS is higher in adolescents involved in CPV. These findings are consistent with previous studies in which PUSNS was associated with a high involvement in several violent behaviors such as peer violence (Martínez-Ferrer et al., 2018), cyberbullying, and dating violence (Giménez-Gualdo et al., 2015).

In addition, adolescents with high CPV are more likely to show higher levels of alexithymia and attitude towards transgression of social norms. Previous studies have shown that adolescents with difficulties in identifying and verbalizing differentiated feelings tend to use violence as a conflict resolution strategy (Aricak & Ozbay, 2016; Garaigordobil, 2017). These findings have also been observed in a sample of male adults in which greater alexithymia also showed higher levels of physical violence (Garofalo, Velotti, & Zavattini, 2018). Regarding the attitude toward institutional authority, the adolescents most involved in CPV have a negative conception of authority figures – formal and informal – and a high perception of injustice. We consider that this result deserves further exploration due to its implications regarding CPV and its relationship with adolescent identity.

As far as parenting styles are concerned, as hypothesized, the indulgent style was the most functional one. Adolescents educated with an indulgent style reported a lower PUSNS, fewer difficulties in identifying emotions, a lower attitude toward the transgression of social norms, and a greater positive attitude toward institutional authority. By contrast, adolescents educated in authoritarian style scored higher in all these variables. These results are consistent with results obtained in other studies in which the relationship between parenting styles and psychosocial adjustment of children was examined (Fuentes et al., 2015; Martínez Pastor, 2017). Thus, the authoritarian style, characterized by high severity and strictness, was closely related to adolescents’ involvement in violent behaviors (Calvete, Orue, & Gámez-Guadix, 2013).

Of particular relevance is the interaction effect between CPV and parenting styles with PUSNS and alexithymia. More specifically, our findings indicated that the authoritarian style was related to a higher PUSNS, especially in adolescents with a high CPV. However, adolescents from families with a predominantly indulgent style reported the lowest levels of PUSNS. Furthermore, adolescents with high CPV and subject to an authoritative parenting style showed higher levels of PUSNS than adolescents with low CPV, regardless of parenting style. In relation to alexithymia, authoritarian, neglectful, and authoritative styles in adolescents with high CPV were associated with greater difficulties in identifying and expressing emotions. Otherwise, adolescents with low CPV, particularly those educated predominantly with an indulgent or authoritative style, are those who reported lower alexithymia.

Previous studies showed that the indulgent style is associated with a low CPV (Moral-Arroyo, Martínez-Ferrer et al., 2015) and with greater emotional stability (Fuentes et al., 2015; Rodrigo, 2016; Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, Martín-Quintana, & Cruz-Sosa, 2016). This suggests that the affective involvement of parents is associated with a better emotional and behavioral adjustment. On the other hand, the authoritarian style has been related to high levels of hostility and violence that, in turn, are related to PUSNS (Calvete et al., 2013; Martínez-Ferrer et al., 2018) and alexithymia (Aricak & Ozbay, 2016; Garofalo et al., 2018). A possible explanation could be that the authoritarian style is characterized by low affection and sensitivity of parents towards their children, as well as poor family communication lacking empathy. This potential lack of affection can also lead to greater difficulty in identifying and expressing emotions, feelings, and desires (Arranz et al., 2016; Fuentes et al., 2015; Gracia, Fuentes, & Garcia, 2010). Alexithymia is also closely related to poor control of impulses and anger (Arancibia & Behar, 2015; Grynberg, Luminet, Corneille, Grèzes, & Berthoz, 2010; Velotti et al., 2017), which, in turn, is linked to adolescents’ involvement in both CPV and PUSNS (Garofalo et al., 2018; Kolko, Kazdin, & Day, 1996; Palavecinos, Amérigo, Ulloa, & Muñoz, 2016). Our results highlight that the authoritative style is associated with higher levels of PUSNS and alexithymia, especially when adolescents are violent towards their parents. Future research could examine other underlying variables in these relationships, such as impulsivity and self-control.

Regarding gender, we hypothesized that relationships between CPV, parenting styles, alexithymia, PUSNS, and attitude towards institutional authority will be different for boys and girls. As expected, results showed that PUSNS scores were similar in boys and girls with low CPV. However, when CPV is high, girls score the highest levels of PUSNS. This is consistent with previous studies in which it is indicated that PUSNS is higher in girls (Kiraly et al., 2014; Martínez-Ferrer et al., 2018). With regard to alexithymia, it is observed that when CPV is high, the difficulty in identifying emotions in girls is greater than in boys, whereas when CPV is low, there are no differences in PUSNS according to gender. These results supported Levant et al.’s (2009) findings suggesting that girls involved in CPV show more alexithymia than boys, whereas in non-violent contexts boys show higher levels of alexithymia than girls.

Our results provide evidence that adolescents with high CPV have, in turn, problems with identifying and expressing their emotions, which could lead them to become more involved in Internet and social networking sites in order to build or improve interpersonal relationships and to regulate their affective states. However, boys use Internet and social networking sites more frequently to have greater self-confidence and self-efficacy (Schimmenti et al., 2017; Scimeca et al., 2014). Future studies can be conducted to explore these relationships.

Finally, the current study is not without limitations. The design of the present study was cross-sectional which did not allow establishing causal relationships between studied variables. Future studies can employ a longitudinal design to further test causality in this relationship. Another limitation is the use of adolescents’ self-reports. In future studies, both parent and adolescent perspectives should be taken into account. Furthermore, our study is based on a survey involving adolescents who were asked how often they had been involved in CPV. This can be considered a sensitive issue leading to possible biases. Despite these limitations, some practical implications are derived from the results of this study, especially relevant in the field of intervention and family education programs. Our findings highlight the potential problematic relationship of adolescents with the Internet and social networking sites, and its links to parenting styles and CPV. Educational programs aiming to strengthen the bond between adolescents and their parents as well as Internet and social networking sites good practices education should be taking into account as promising preventive strategies.