Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Educación Médica

versión impresa ISSN 1575-1813

Educ. méd. vol.6 no.3 jul./sep. 2003

Conferencia magistral

Miércoles 22 de octubre - 19,30h

Aula Pittaluga

Linking Appraisal of On-the-Job Professional

Competencies with Education

Miriam Friedman Ben-David and David Snadden, Dundee, Escocia.

Work Funded by the Scottish Council for Postgraduate Medical and Dental Education (SCPMDE)

Over the years Pre Registration House Officers (PRHOs) expressed dissatisfaction with the level of supervision, teaching and feedback they receive from their consultant supervisor (Paice et al 1997). Extensive work was done to define appropriate tasks for the pre-registration year (Stewart et al 1999), however the optimal delivery of education for the tasks identified still needs to be resolved. This situation seems to be further amplified by the workload problems within the NHS, the move to a consultant led service in the context of insufficient consultant numbers and the NEW Deal; the reduction in junior doctors hours, leading to the introduction of partial and full shifts. Within these constraints the consultant supervisors are faced with the impossible task of appraising PRHOs for their readiness to be fully registered at the end of their PRHO training. Consequently the PRHOs' education as well as their appraisal is being re-examined as a subject for national reform if seen in the wider context of change in medical education in UK. These changes address appraisal and re-validation for the whole of the medical profession in which the PRHO year may be seen as significant training period leading to the initial validation of doctors as independent practitioners. Once the PRHO is fully registered, he/she is qualified as doctors until their next validation, which in most cases occurs a few years later.

The lack of standardisation of appraisal methods, the absence of direct observations of PRHO performance in most programmes and undefined expected outcomes are only few of the current problems that may lead to awarding full registration to incompetent PRHOs.

Salter (1995) compared the education of pre-registration house officers in the UK with the US residency system. He concluded that the self-education of junior doctors should be maximised and posts analogous to the US "Chief Resident" could be considered including significant investment in all aspects of learning and feedback. Models of pre-registration house officers training in General Practice provide insight into valuable educational experiences such as individual training programmes, where PRHOs assume responsibilities for own patients, and having time set aside for learning. (Williams, 2001). In other countries, evaluation studies are performed to evaluate Interns mastery of important competencies. In Norway, Interns were surveyed to determine the degree of acquisition of potentially life-saving skills (Falck and Brattebo,1997). Only half of the Interns were found to acquire the skills. In Australia, differences in Interns performance due to gender, undergraduate curricula, and school of origin were investigated using a 13 competence dimension evaluation form (Rolfe et al, 1995, Rolfe et al, 1998, Pearson et al, 1998). However, these are all isolated examples of approaches to PRHO appraisal that should be considered within the global needs of the local health system.

This paper describes a PRHO appraisal model developed in Scotland, which incorporates professional and personal growth of the young doctors. The model identifies early problems with PRHO performance; it utilises a wide range of appraisal input. Appraisal results are translated into educational sessions, which enforce contact time with clinical tutors. A portfolio approach is employed to provide evidence, enhance PRHO progress and inform the appraisal system.

In 1999, the Scottish Council for Postgraduate Medical and Dental Education (SCPMDE), initiated a national research study to pave the way for a long awaited educational reform in PRHO training in Scotland. Curriculum changes as well as innovative approaches to PRHO appraisal comprised the main components of this nation-wide project. The four Postgraduate regional offices in Scotland are collaborating on the various aspects of the projects' research activities.

Background

In August 1998, standard documentation for PRHO performance appraisal was introduced in the form of a Record of Progress and Assessment booklet. The current Scottish system of Record of Progress and Assessment signifies the first step in the desired direction of standardising the PRHO appraisal forms, the introduction of uniformed national requirements for PRHOs for obtaining full registration and the enforcement of face to face periodical appraisal sessions of PRHOs and their educational consultant. However, the need to define the key competencies to be achieved in the PRHO year, the dissatisfaction with the box ticking exercise in completing the forms as well as the problems in securing the appraisal sessions are only a few of the concerns regarding the Record of Progress and Assessment. There was also a general feeling that the current system does not identify adequately the incompetent PRHO, and the trail of documentation is not sufficient to stop incompetent Junior Doctors from obtaining full registration.

The PRHO Appraisal Model

The aim of this study was to develop a comprehensive systematic and standardised National PRHO appraisal system, which will outline the competencies and behaviours to be appraised as well as develop progression benchmarks and link appraisal to education.

The initial data gathering of the appraisal project concentrated on four main areas:

1. Identify the current problems in PRHO appraisal

2. Explore the key competencies to be appraised

3. Identify progression benchmarks, which highlight PRHO professional and personal growth

4. Develop an appraisal model linked to PRHOs' "on the job" education

Methods

Focus Groups

During the period Nov 1999-2001, focus Groups were conducted with PRHOs (4 sessions), Educational consultants (2 sessions), Specialist Registrars (2 sessions), Nurses (2 sessions), SHOs (2 sessions); in the North Eastern and Eastern region in Scotland. Focus group members were encouraged to discuss what works and what does not work in the current PRHO appraisal system.

The Scottish Doctor 12 Learning Outcomes based on the university of Dundee Medical School model (Harden, 1999) was presented to focus group members as a framework to stimulate the group discussion. Group members were probed to indicate critical behaviours, which separate the competent PRHO from the incompetent. The question of who knows the PRHO was explored in depth. Group members were asked to reflect on behaviours they felt the PRHOs are showing progress during their year of training. Qualitative analysis generated information on the above study areas.

Interviews

The Educational Development Unit at the CENTRE FOR Medical Education in Dundee, a unit of SCPMDE, currently coordinates a national consensus study for the development of learning outcomes for the PRHO year. One of the methods employed in this study was an interview with 40 randomly selected PRHOs - 10 from each of the four Scottish regions. The semi-structured interviews were designed to elicit new information relative to the 12 undergraduate learning outcomes incorporating the Junior Doctors' perception. A qualitative analysis using ethnographic software generated information regarding PRHOs' important competencies, thus transforming the learning outcome model from undergraduate to the postgraduate PRHO year. PRHO narratives described the new PRHO competence behaviours under each of the 12 outcomes. The PRHOs narratives included examples of progress or improvement in skills, over the year of PRHO training. It should be noted that PRHOs were not asked during the interviews to reflect on progress, but rather information about progress was available as PRHOs reflected on their experiences.

Results

Three sets of data were obtained from the Focus Groups and the Interviews combined:

a) Current Problems:

The following lists highlights of the current problems identified:

1. Lack of behavioural definitions and manifestation of clinical competencies

2. No early detection of poor performers

3. No adequate objective documentation which withstands litigation

4. No sufficient tools to separate the incompetent PRHOs from the competent PRHO.

5. Educational system does not target professional and personal growth.

6. No opportunities for feedback and tailored interventions.

7. Role of educational supervisor is not well defined.

8. The need to identify educational support to meet the challenge of PRHO training.

b) Key competencies to be appraised

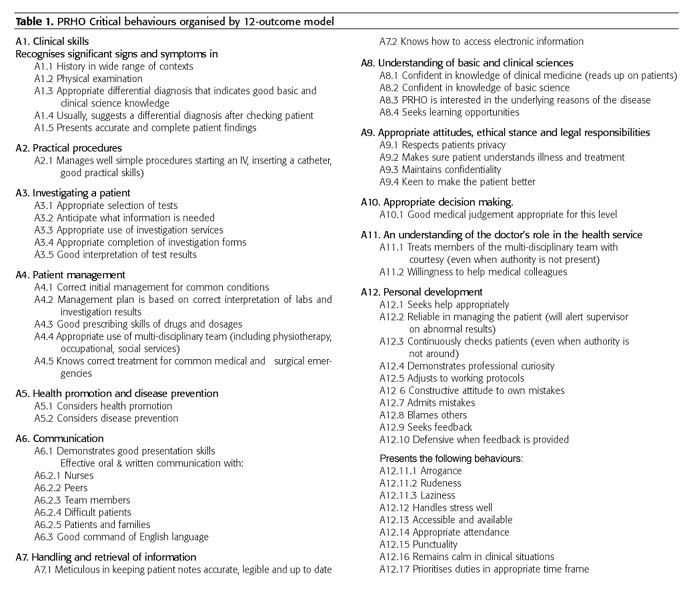

Grouped under the 12 Learning Outcomes, a list of 52 key appraisal behaviours were identified (Table 1), which focus group members regarded as critical for separating the competent PRHOs from the incompetent.

c) Progression Benchmarks

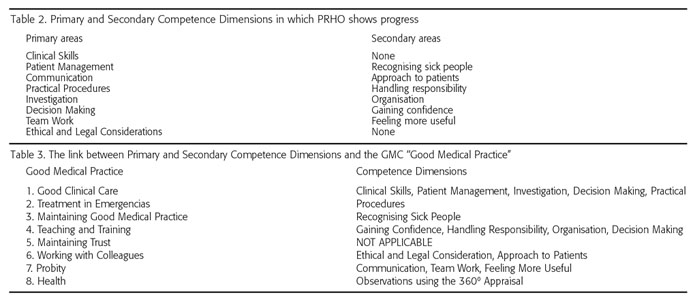

Eight primary competence dimensions and 6 associated secondary dimensions were identified as areas in which professional and personal progress is evident (Table 2). Each primary and secondary dimension included a set of benchmark behaviours, which describes the scope of progression over the PRHO year.

Table 3 demonstrates the link between the Primary and Secondary Competence Dimensions identified in the PRHO year for appraisal purposes and the dimensions presented in the GMC "Good Medical Practice". The more advanced the Postgraduate training, the closer the link to the GMC "Good Medical Practice". For example, during the PRHO year, less emphasis is given to PRHOs' skills in teaching. Probity as well as Working with Colleagues are in early developmental phase.

The PRHO Appraisal Model

The proposed appraisal model responds to the study findings incorporating the key elements of appraisal and education. In the first six months, upon entering the first post, all PRHOs are appraised by employing a 52 item 360º evaluation form. The forms are completed by a Nurse, SHO, Specialist Registrar and a Consultant. The 360º evaluation marks are entered into a computerised database. The computer generates a summary of results from all four appraisers per PRHO. A computer diagnostic profile summarises competencies and behaviours, which were flagged. Flagging behaviour implies a mark of 5 or lower on a 1-9 point scale. PRHOs who obtained satisfactory 360º appraisal with minimal flagging will proceed to a regular track; those who obtained a flagged profile will proceed to a diagnostic track.

The primary and secondary competence dimensions summarised in the diagnostic profile constitute the "menu" for selecting a 20-minute educational session for the regular and the diagnostic tracks. The Educational sessions follow a portfolio format in which the PRHO prepares evidence in writing with relation to a selected competence dimension. A consultant or registrar review the evidence with the PRHO according to a template and discuss the progression benchmarks assigned to this session, which are used as evaluation for the session. At the end of the educational session, the appraiser fills up the evaluation form for this session and both appraiser and appraisee sign the form. Recommendations are made by the appraiser for future work or remediation. In each subsequent educational session previous recommendation are examined. In the first 6 months, a regular track PRHO attends 3 core educational sessions. However, PRHOs with a flagged diagnostic profile will attend additional educational sessions according to the competence dimensions identified as deficient.

At the end of the first 6 months, based on the PRHO's documentation, the Postgraduate Dean will approve PRHO continuation of the programme or as pending further review. It is possible that a PRHO who started a regular track will be identified during the educational sessions as needing diagnostic sessions and vice versa. During the subsequent 6 months, the same process will be repeated.

Upon completion of the PRHO year, the documentation trail will supply ample evidence to the Postgraduate Dean, as to whether the PRHO should proceed to full-registration or is not fit for practice.

The regular track documentation trail will include two 360º diagnostic profiles and six evaluations of Educational Sessions. The Diagnostic track documentation will include the above information plus evaluations from the additional Diagnostic educational sessions.

Since February 2001, 2 pre-pilot studies were conducted in 5 hospitals in Scotland in which the 360º Instrument was administered and educational sessions were observed. Future pilot studies are planned if the PRHO appraisal model will be implemented in Scotland.

Summary

The proposed PRHO appraisal system links appraisal to education. Multiple appraisers' inputs ensure a global picture of PRHO performance. PRHOs are appraised using on-the-job authentic behaviours. Expected outcomes are communicated to PRHOs on entry and diagnostic reports are associated with those outcomes. Consequently PRHOs obtain early feedback on potential problems as well as on adequate performance. A portfolio approach (Friedman, 2001, Snadden, 1999) further links education and appraisal. PRHOs present evidence of achieving expected outcomes by using examples "in context". They discuss their work, reflect on their own interpretation, The appraisers use the evidence to identify the progression level on which the PRHO operates. Progression benchmarks assist both PRHO and appraiser to discuss their current level of performance. The appraiser may initiate all other forms of follow up as long as they are documented. PRHOs who participated in an educational session made the following remarks:

"It is the first time I felt like I am treated as a true professional."

"The educational sessions enforce protected time and the educational load is distributed among a number of clinical tutors. The PRHO is responsible to co-ordinate the required sessions and to ensure that at the end of 6 and 12 months of the program, their personal PRHO file contains all required documentation for proceeding to full registration."

References

1. Falck G. and Brattebo G., Skills of Pre-registration House Officers: gender differences reported in Norway. Medical Education, 31, 1997 [ Links ]

2. Friedman Ben-David M., Davis M.H., Harden R.M., Howie P.W., Ker J., Pippard M.J., Portfolios as a method of student assessment, AMEE Guide No. 24, 2001 [ Links ]

3. Harden R.M., Crosby J.R., Davis M.H., Friedman Ben-David M. Outcome-based Education from competency to meta-competency: a model for specification of learning outcomes, Medical Teacher, Vol. 21, No.6, 1999 [ Links ]

4. Paice E., Moss F., West G., Grant G., Association of Use of a Log Book and Experience as a Pre-registration House Officer: Interview Survey, BMJ, January, 1997 [ Links ]

5. Pearson S., Rolfe I.E., Henry R.L., The Relationship between assessment measures at Newcastle Medical School (Australia) and performance ratings during internship, Medical Education, 1998 [ Links ]

6. Rolfe I.E., Andren J.M., Pearson S., Hensley M.J., Gordon J.J, Clinical Competence of Interns, Medical Education, 1995 [ Links ]

7. Rolfe I.E., Pearson S., Fardell S.D., Kay F.J., Monitoring the Performance of Junior Doctors in the First Two Years of Postgraduate Training, Education for Health, Vol. 11, No.2, 1998 [ Links ]

8. Salter R., The US Residency Programme - Lessons for pre-registration house officer education in the UK?, Postgraduate Medical Journal, Vol 71 (835), 1995 [ Links ]

9. Snadden D. Portfolios - attempting to measure the unmeasureable? Medical Education 1999;33478-9 [ Links ]

10. Stewart J., O'Halloran C., Harrigan P., Spencer J.A., Barton J.R., Singleton S.J., Identifying appropriate tasks for the pre-registration year: modified Delphi technique. BMJ, July 1999 [ Links ]

11. Williams C., Cantillon P., Cochrane M., The clinical and educational experiences of pre-Registration house officers in general practice, Medical Education, Vol. 35(8), 2001 [ Links ]