Work engagement reflects how involved people are in the tasks that they have to do as part of their jobs and is closely related to their job performance (Bakker et al., 2011; Bakker & Oerlemans, 2019; Laguna et al., 2017; Martínez et al., 2020). The concepts of employee engagement and work engagement have usually been used interchangeably (Guest, 2014); however, work engagement refers to an employee's relationship to their work at the individual level, whereas employee engagement is about the relationship between the employee and their organization (Salanova et al., 2005; Tisu et al., 2020). Most researchers consider work engagement to be the effective involvement and participation of people in their work, which produces a positive affect associated with the job and the workplace environment (Castellano et al., 2019; Maslach et al., 2001; Rothbard & Patil, 2012; Salanova & Llorens, 2008). Despite the widespread use of the term, work engagement does not have a single definition, nor a uniform conceptualization, and different approaches suggest differentiation of engagement as a trait, as a psychological state, or as a behavior (Macey & Schneider, 2008; Solomon & Sridevi, 2010).

Work engagement is an important factor in the management of organizations due to its influence on companies' efficiency and competitiveness, along with its links to higher levels of both individual and organizational performance (Barría-González et al., 2021; Halbesleben, 2010; Lesener et al., 2020; Martínez et al., 2020). Employees who are engaged within the organization have been shown to be more proactive, to encourage innovation, and to make efforts to improve the organization's results (Harter et al., 2002; Ruiz-Zorrilla et al., 2020). The higher levels of energy, responsibility, enthusiasm, and effective connection to the job associated with work engagement underscore why companies are interested in understanding the factors that determine it.

How engaged employees are with their work is determined by both personal characteristics and factors related to the organizational climate (García-Arroyo & Segovia, 2021). There is no unequivocal answer about the extent to which one predominates over the other, which is one of the main objectives of the present study. When workers develop and use their personal resources, they tend to exhibit greater work engagement (Airilia et al., 2014; Bhatti et al., 2018; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). Emotional intelligence demonstrates a positive effect on work engagement (Barreiro & Treglown, 2020; Brunetto et al., 2012; Extremera et al., 2018; Ravichandran et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2015), as does a positive affective experience in the workplace (Fisher, 2010; Martos Martínez et al., 2021; Salas-Vallina et al., 2017). Emotional intelligence and personal happiness may act as resources that allow employees to enthusiastically deal with the demands of work and encourage work engagement (Cohn et al., 2009). The connection between personality characteristics and work engagement has been widely studied (Bakker & Leiter, 2010; Lisbona et al., 2018). Personality traits can be measured at different levels of conceptual breadth (Soto & John, 2017). A broad character trait can summarize a large amount of behavioral information and predict a wide range of important criteria, whereas more restricted trait measures more accurately express a specific behavioral description and can predict criteria that are closely linked to that description (John et al., 2008; Postigo et al., 2021). This is why it is important to distinguish between studies focusing on broad, Big Five-type, personality traits and those which use more specific personality traits. Various studies have found positive relationships between work engagement and general personality traits (Bakker et al., 2012; Bhatti et al., 2018; Hau & Bing, 2018; Martos Martínez et al., 2021; Zaidi et al., 2013), with agreeableness being the trait with the weakest relationship to work engagement (Janssens et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2009). Other authors have used specific personality traits to examine the relationship with work engagement. Traits such as self-efficacy, proactivity, innovation, stress-tolerance, and optimism have been positively related to employees' work engagement (Bhatti et al., 2018; Contreras et al., 2020; Li et al., 2017; Lisbona et al., 2018; Perera et al., 2018; Ocampo-Álvarez et al., 2021).

With regard to the organizational attributes that affect work engagement, studies have found clear connections between both physical and organizational characteristics of a job (Saks, 2019; Xanthopoulou et al., 2007). Saks (2019) suggested that giving employees opportunities to put diverse skills into practice in an interesting, challenging job is likely to lead to high work engagement. Employees' perceptions and opinions about the psychosocial context and the specific characteristics of the organization they work for influence their behavior and affect work engagement (Bartram et al., 2002; Basinska & Rozkwitalska, 2020; DeCottis & Summers, 1987; Dessler, 2008; González-Verde et al., 2015; Quiñones et al., 2013; Tandler et al., 2020). The various facets that may comprise a good organizational climate, such as organizational trust, the absence of workplace tension, social support, remuneration, and job satisfaction, lead an employee to be engaged with their work (Barría-González et al., 2021).

In this context, the present study has two objectives. Firstly, it aims to assess the weight of personal characteristics and organizational attributes in predicting the levels of employees work engagement. Personal characteristics include both general and specific personality traits, emotional intelligence, and personal happiness. The organizational attributes cover workplace happiness and organizational climate. Secondly, given that previous research has shown that people's perceptions of the psychosocial context and the specific characteristics of the organization influence behavior and impact their engagement with their work (Barría-González et al., 2021; Hermosa-Rodríguez, 2018; Murphy & Reeves, 2019), the study aims to assess the possible moderating effect of work-context variables (happiness and organizational climate) on the personal variables that are most important in predicting work engagement.

Method

Participants

The final sample comprised 286 employees and 17 cases were removed for giving insufficiently rigorous answers according to the attentional control scale. The majority (83.5%) were Spanish nationals and 16.6% were from other Spanish-speaking countries. The mean age of the sample was 44.51 years old (SD = 8.76), with a range between 24 and 67. Just over half (55.2%) were women and 73.8% had university-level qualifications. Just under a quarter (23.8%) had higher level management jobs, 33.6% were middle managers, 24.5% were technical-level employees, and 18.1% were skilled workers.

Instruments

Work Engagement Scale (ESCOLA; Prieto-Díez et al., 2021).

ESCOLA is a scale with 10 items that evaluates work engagement. The responses are given on a Likert-type scale from 1 to 5, where 1 indicates complete disagreement and 5 indicates complete agreement. The scale has a reliability (α) coefficient of .92 and evidence of convergent validity (Prieto-Díez et al. 2021). The reliability in the present study was excellent: α = .92.

Battery for the Evaluation of Enterprising Personality (BEPE; Cuesta et al., 2018).

The BEPE is an 80-item questionnaire which evaluates eight dimensions of enterprising personality: self-efficacy, autonomy, innovation, internal locus of control, achievement motivation, optimism, stress-tolerance, and risk-taking (Cuesta et al., 2018; Muñiz et al., 2014; Postigo et al., 2020). The items use a Likert scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). The instrument exhibits a good fit to a bifactor model, with excellent reliability for the eight dimensions and the scale overall, and ? coefficients between .91 and .97 (Cuesta et al., 2018). In the present study, (α) coefficients were: enterprising personality = .97; self-efficacy = .91, autonomy = .83, innovation = .92, internal locus of control = .88, achievement motivation = .90, optimism = .92, stress-tolerance = .85, and risk-taking = .90.

Brief Organizational Climate Scale (CLIOR-S; Peña-Suárez et al., 2013)

The CLIOR-S is an instrument containing 15 items which assess the perceived organizational climate. The items use a Likert-type scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). The instrument has a reliability coefficient of .94 and a correlation of .86 with the longer version (Peña-Suárez et al., 2013). The reliability in the present study was excellent: α = .94.

Overall Personality Assessment Scale (OPERAS; Vigil-Colet et al., 2013).

OPERAS evaluates the five broad personality traits according to the Big Five model (extraversion, emotional stability, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and openness to experience; Costa & McCrae, 1992). There are 7 items for each dimension, using a Likert-type scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). The subscales present reliability (α) coefficients between .71 and .86, and the instrument has adequate evidence of convergent validity (Vigil-Colet et al., 2013). In the present study the (α) coefficients of reliability were: extraversion = .80, emotional stability = .76, conscientiousness = .67, agreeableness = .68, and openness to experience = .70.

Trait Meta-Mood Scale (TMMS-24; Fernández-Berrocal et al., 2004).

Emotional intelligence was assessed using the Spanish version of TMMS-24 (Extremera & Fernández-Berrocal, 2005; Fernández-Berrocal et al., 2004). This questionnaire has three dimensions: attention to emotion (8 items), which evaluates a person's tendency to observe and think about their own thoughts and emotional states; emotional clarity (8 items), which evaluates the extent to which people understand their own emotional states; and emotional repair (8 items), which evaluates people's perceptions of how they regulate their own feelings. The Spanish version exhibits reliability coefficients (α) above .85 for each of the subscales (Fernández-Berrocal et al., 2004). The items use a Likert scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). The (α) reliability in the present study was .83 for attention, .76 for clarity, and .86 for repair.

Happiness at Work Scale (Ramírez-García et al., 2019).

This scale, developed in Spain, has 11 items which use a Likert scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree). The instrument has two dimensions, the first covers factors related to the workplace (α = .91), while the second includes personal factors from the employee (α = .72). The reliability (α) in the present study was .91 for the first dimension and .75 for the second.

Attentional Control Scale

This is a scale with 10 Likert-type items with 5 response options each. The objective of this scale is to detect participants who answer without sufficient care and attention. The items are of the type "In this question, please select item four", and were interspersed randomly between the items of the various instruments. Participants who answered two or more questions incorrectly were eliminated from the study.

Procedure

Data collection took place online. Links to the questionnaire were disseminated through employee associations and professional social networks. Data collection took place between 3 April and 20 May 2020. Participants were informed that the study had nothing to do with the COVID-19 crisis or the lockdown, and responses should refer to the participants' normal working situations. The items from the instruments were randomly distributed. The questionnaire took an average of 40 minutes to complete. Participants received no kind of recompense for their participation. The anonymity of each participant was ensured and data confidentiality was maintained in strict accordance with data protection legislation (Ley Orgánica 3/2018, de 5 de diciembre, de Protección de Datos Personales y garantía de los derechos digitales).

Data Analysis

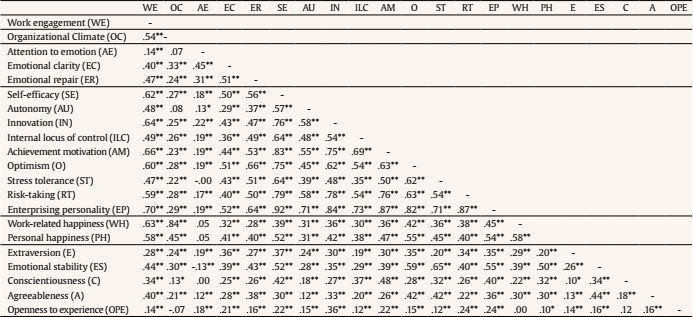

First, Pearson correlations were calculated between the variables used in the study: a) work engagement, b) the Big Five personality traits, c) eight specific traits of enterprising personality, d) three dimensions making up emotional intelligence, e) two happiness dimensions (personal and work-related), and f) organizational climate.

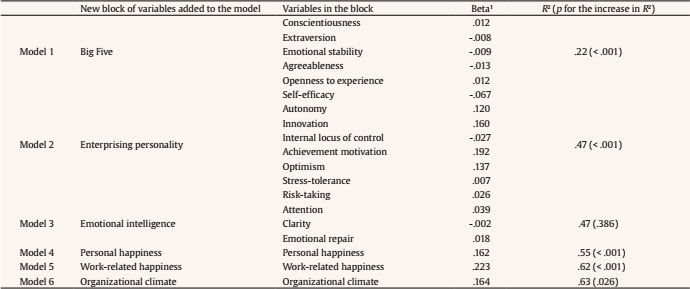

Secondly, a hierarchical linear regression was performed, using work engagement as the criterion variable, and adding a set of predictor variables at each step, from the variables measuring personal characteristics to variables focused on organizational attributes. Specifically, the variables were: a) The Big Five personality traits, b) eight specific dimensions of enterprising personality, c) three dimensions of emotional intelligence, d) personal happiness, e) work-related happiness, and f) organizational climate. The coefficient of determination (R2) was used to examine the percentage of variance explained.

Finally, the moderating capacity (e.g., Ato & Vallejo, 2011; Fatima et al., 2021) of organizational variables in the relationship between the personal variables and work engagement was assessed. The specific personal variables considered were those that were statistically significant in the final step of the previous hierarchical regression model and the organizational variable was the organizational climate. In addition, the moderating capacity of work-related happiness on the relationship between personal happiness and work engagement was also examined.

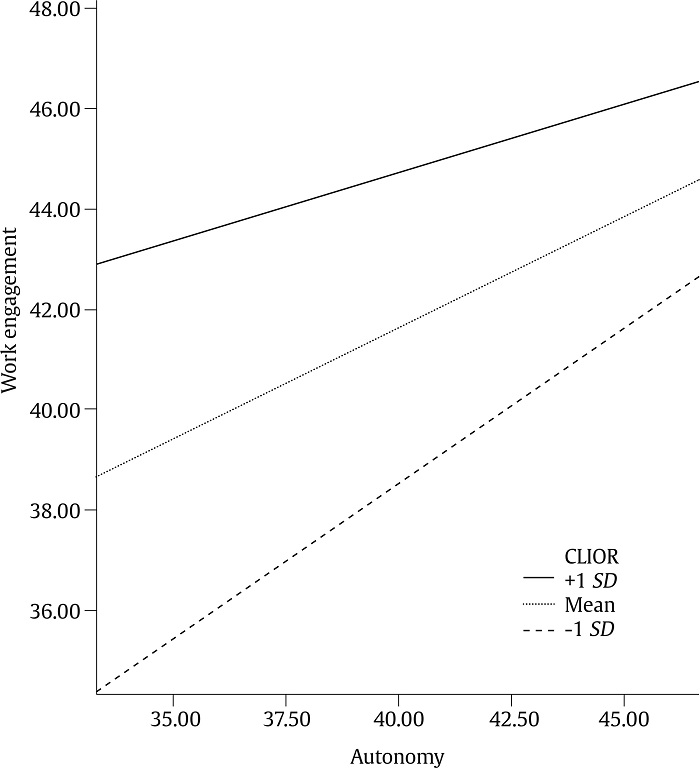

In each of the proposed regression models, organizational climate and work-related happiness had a moderating role in the relationship between the personal variable being examined and work engagement (Figure 1). Where the interaction was statistically significant, a simple slope analysis was performed between the predictor personal variable and work engagement at high (+1 SD), moderate (0 SD), and low (-1 SD) levels of the moderating organizational variable.

All analyses were performed using SPSS 24 (IBM Corp, 2016) and the PROCESS program (Hayes, 2017).

Figure 1. Representation of the Moderation of Organizational Variables on the Relationship between Personal Variables and Work Engagement.

Results

As Table 1 shows, the correlations between the predictor variables and work engagement were very strong, particularly for enterprising personality (r = .70). In the variables related to personal characteristics, work engagement as assessed via ESCOLA exhibited a positive correlation with all of the BEPE dimensions and strong correlations with: achievement motivation = .66, innovation .64, self-efficacy = .62, optimism = .60, and risk-taking = .59. The personal happiness dimension also demonstrated a correlation of .58 with work engagement. Weaker correlations were found with the Big Five personality traits and with the three emotional intelligence dimensions. In terms of organizational variables, there were strong correlations between engagement and organizational climate (r = .54) and work-related happiness (r = .63).

Hierarchical linear regression was performed to examine the relationships between work engagement and the predictor variables as a whole. Table 2 shows the variables added to the model in each step, along with the increase in the coefficient of determination (R2) produced by the addition of the set of variables in that step. The Big Five traits explained 22% of work engagement, a value that rose to 47% when the eight specific traits of enterprising personality were added, with innovation being the only significant variable in the second step (p < .001). On adding the three variables making up emotional intelligence (step three), the increase in explaining work engagement was not significant. There was a notable increase in explaining work engagement on the addition of personal and work-related happiness variables (steps four and five). In the final model (step six), organizational climate was added, which produced a significant increase in the explanation of work engagement. The variables which were ultimately statistically significant in the explanation of employees' work engagement were achievement motivation and personal happiness (as personal variables), and work-related happiness and perceived organizational climate (as work-related variables). The final standardized regression equation (model 6) for predicting work engagement is given in Table 2 in the column which shows beta for each of the variables.

Table 2. Hierarchical Linear Regression Model for Predicting Work Engagement

Note1Beta for each variable corresponds to the definitive model (model 6).

Once the predictive power of each block of variables on work engagement had been analyzed, the moderating effect of the organizational variables on the relationship between personal variables and work engagement was examined, specifically, innovation, autonomy, and achievement motivation were the most important variables in predicting work engagement. Therefore, we examined whether the organizational climate moderated the relationship of each of these variables with work engagement. In each model, organizational climate was used as a moderating variable and work engagement as a dependent variable. In the first model, the predictor variable was innovation. There were statistically significant results for the coefficients of innovation (β = .736, CI 95% [.330, 1.141], p < .001) and organizational climate (β = .365, CI 95% [.049, .682], p < .001), but not for the interaction (β = -.004, CI 95% [-.011, .003], p = .275). The model explained 52.4% of the variance in work engagement. The second model used achievement motivation as the predictor variable. There were statistically significant results for the coefficients of achievement motivation (β = .610, CI 95% [.184, .1.04], p = .005), but not for organizational climate (β = .210, CI 95% [-.135, .554], p = .232), or for the interaction (β = -.001, CI 95% [-.008, .007], p = .917). The model explained 53.3% of the variance. Finally, the third model used autonomy as the predictor variable. In this model both autonomy (β = 1.18, CI 95% [.634, 1.729], p < .001) and organizational climate (β = .796, CI 95% [.397, 1.195], p < .001) were statistically significant, with the interaction also being significant (β = -.014, CI 95% [-.023, -.004], p < .001), indicating the moderating role of organizational climate on the relationship between autonomy and work engagement, explaining 49.3% of the variance. A simple slope analysis was then performed from this model between the personal predictor variable and work engagement at high (+1 SD), moderate (0 SD), and low (-1 SD) levels of the moderating organizational variable (Figure 2). The chart shows how the relationship between autonomy and work engagement is moderated by the organizational climate. There is a stronger relationship when the organizational climate is low (-1 SD), and as the organizational climate improves, the relationship between autonomy and work engagement weakens (+1 SD).

Note. CLIOR = organizational climate; +1 SD = one standard deviation above the mean; -1 SD = one standard deviation below the mean.

Figure 2. Model of Moderation of Organizational Climate on the Relationship between Autonomy and Work Engagement

In addition, given the importance demonstrated by happiness, both at the personal and organizational level, a model was specified in which work-related happiness moderated the relationship between personal happiness and work engagement. There were statistically significant results for the coefficients of personal happiness (β = .83, CI 95% [.414, 1.26], p < .001) and work-related happiness (β = .515, CI 95% [.237, .792]; p < .001), but not for the interaction (β = -.009, CI 95% [-.020, .001], p < .001); the model explained 46.5% of the variance.

Discussion

Interest in work engagement in the business world has led to the need to document the relationships with other positive variables linked to job performance. Work engagement is a very important variable in the organizational sphere (Bakker et al., 2011; Bakker & Oerlemans, 2019; Laguna et al., 2017; Martínez et al., 2020) and it depends on personal and contextual factors (e.g., García-Arroyo & Segovia, 2021; Saks, 2019; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). The aim of the present study was to examine the influence of personal resources (general and specific personality traits, emotional intelligence, and personal happiness) and contextual resources (work-related happiness and organizational climate) on employees' engagement with their work. The study has shown that, on the one hand, both personal and work-related resources have some kind of impact and are predictors of work engagement, with the balance tipped towards the personal factors (Bakker et al., 2011; Bakker & Oerlemans, 2019; Laguna et al., 2017; Lisbona et al., 2018; Martos Martínez et al., 2021) and, on the other hand, that organizational components play a moderating role between certain personal variables and a person's engagement (Quiñones et al., 2013; Southwick et al., 2019).

The results show that the Big Five-type general personality traits had some predictive capacity over work engagement (Bakker et al., 2012; Bhatti et al., 2018; Hau & Bing, 2018; Martos Martínez et al., 2021; Zaidi et al., 2013), although that capacity improved notably when specific traits of enterprising personality were also used. These results are consistent with previous studies (Leutner et al., 2014; Postigo et al., 2021; Rauch & Frese, 2007) that showed how the evaluation of more specific behaviors more accurately expressed a specific behavioral description and could predict criteria that were closely linked to that description (John et al., 2008; Soto & John, 2017). This indicates, then, that people who are more autonomous and more innovative (see Cuesta et al., 2018), with certain tendencies towards intra-entrepreneurialism (Mumford et al., 2021), tend to be more committed to their work and make more efforts to improve organizational results (Harter et al., 2002; Ruiz-Zorrilla et al., 2020).

In contrast, despite the fact that emotional intelligence has been shown to be related to work engagement (Brunetto et al., 2012; Extremera et al., 2018; Ravichandran et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2015), its influence seems to vanish when employees' personality traits are considered. This may be because variables such as stress-tolerance and optimism are closely related to emotional intelligence (e.g., emotional repair-optimism, r = .66; emotional repair-stress-tolerance, r = .51), meaning that the relationship between work engagement and emotional intelligence may be explained by people's levels of psychological empowerment (Alotaibi et al., 2020; Gong et al., 2020). Happiness demonstrated the expected results. Ramírez-García et al. (2019) considered two factors related to worker happiness, one which included a worker's personal factors, and the other which was about aspects of work environment. Personal happiness slightly increased the prediction of work engagement, because there are certain aspects related to happiness and wellbeing that are not only explained by personality and which lead the employee to be engaged with their work (Fisher, 2010; Martos-Martínez et al., 2021; Salas-Vallina et al., 2017).

Both work-related happiness and organizational climate improved the prediction of employees' work engagement, increasing the variance explained from 55 to 63%. This finding, in line with other studies (Barría-González et al., 2021; Bartram et al., 2002; Basinska & Rozkwitalska, 2020; DeCottis & Summers, 1987; González-Verde et al., 2015) underscores the importance of organizational aspects (over and above personal resources) such as the absence of workplace tension, organizational trust, and social support when motivating workers.

Given the importance of these two (organizational and personal) components when attempting to explain a person's engagement with their job, the moderating role of the organizational components in the relationship between personal variables and work engagement was examined. The organizational climate exhibited a moderating role in the relationship between people's autonomy and their work engagement. People for whom there was a low-scoring organizational climate demonstrated stronger positive relationships between their autonomy and their work engagement than people who perceived better organizational climates. People's autonomy seems to play an important role in their work engagement, although its influence is weaker if work environment is perceived as excellent (Barría-González et., 2021; Gorostiaga et al., 2022; Murphy & Reeves, 2019; Yagil & Oren, 2021).

Various studies have indicated how important it is for work engagement to give workers a certain amount of control over their work, giving them autonomy and the ability to make decisions about tasks and encouraging them to develop their own capabilities (De la Rosa & Jex, 2010; García-Alba et al., 2021, 2022; Karasek, 1979). This suggests important implications for professional practice, where organizations must consider both the levels of autonomy they offer their staff about how they do their jobs and certain organizational aspects that should be addressed when designing strategies aimed at strengthening work engagement.

The conclusions of this study are clear and, as in almost every case, both personal and contextual resources are important. A person with an ambitious perception of themselves when they do things, who works hard, who is responsible and who puts forward new ideas and suggestions, who works autonomously and independently, and who has high tolerance to adversity is someone who will engage with their work. However, if this person finds themselves in a hostile, unstimulating work environment, this engagement may be weakened by the organizational climate, in which they may perform worse, or even give up altogether if the opportunity arises (Henares-Montiel et al., 2021; Sora et al., 2021; Southwick et al., 2019).

The present study has some limitations. As it deals with a sample of employees from various companies, the organizational climate variables provide heterogeneous information of the perception of climate in the different work contexts of each participant. In addition, it would be interesting to analyze the results of the study considering variables such as the organizational hierarchy that employees are part of.