INTRODUCTION

Coaches have a key role in sports settings because of the relevance of their work to the performance of teams. Within the context of professional sports, coaches are constantly pressed by athletes and their relatives, managers, fans and the media, which renders them vulnerable to workplace stress (Knight & Hawoord, 2009; Olusoga, Butt, Hays & Maynard, 2009). Outside the elite context, coaches are under the same pressure (Frey, 2007).

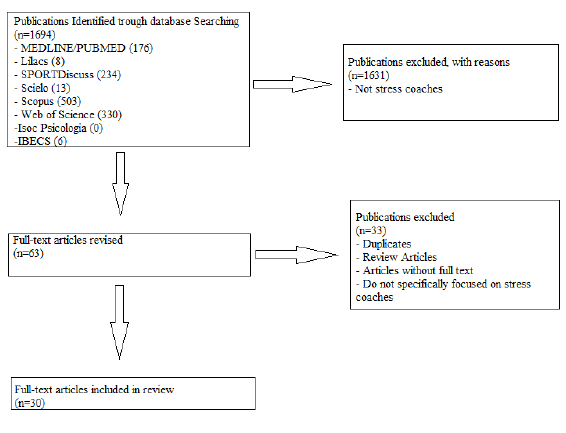

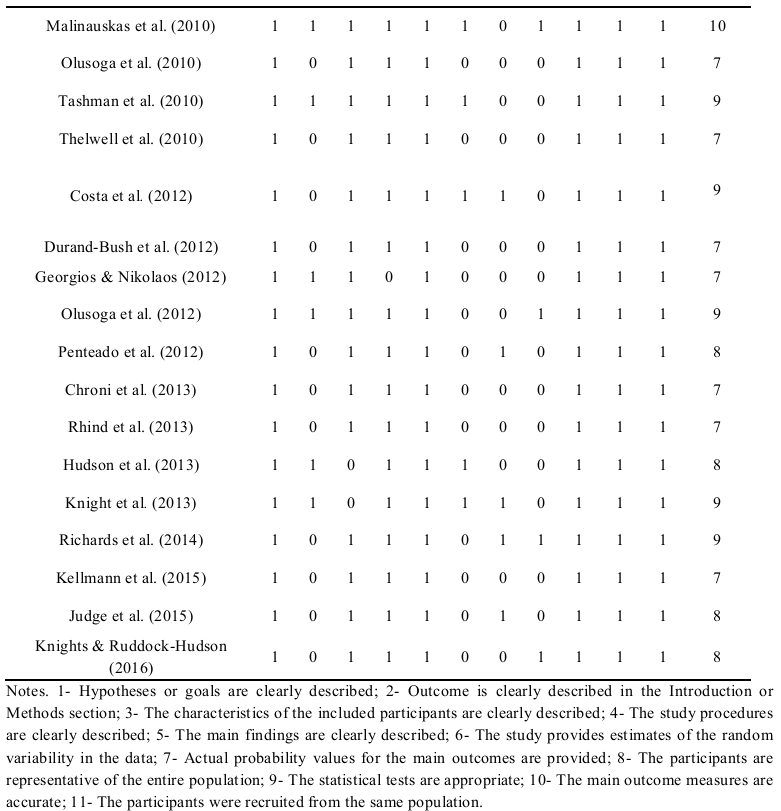

The literature about stress in sports settings indicates that greater attention has been paid to athletes' responses to stress than coaches' responses to stress (Fletcher & Scott, 2010; Frey, 2007). The scarcity of studies on coaches' stress may be explained by a lack of instruments scientifically validated for this purpose (Costa, Ferreira, Penna, Samulski & Moraes, 2012a; Goodger, Gorely, Lavallee & Harwood, 2007) and by difficulties accessing such professionals during training sessions and competitions, particularly in high-performance sports (Costa, Gomes, Andrade & Samulski, 2012b; Olusoga et al., 2009). Another relevant factor is the sports managers' lack of information on the deleterious effects of stress on athletes and clubs managed by stressed coaches. Although athletes are periodically subjected to health assessments, managers do not manifest a similar concern for coaches (Drezner et al., 2013; Harmon, Asif, Klossner & Drezner, 2011). As a rule, the latter are subjected to medical check-ups at the time they are hired or leave the job or when they exhibit a health problem at work. To summarize, sports institutions rely on coaches to care for their physical and mental health by themselves. Figure 1, Table 1

RESULTS

Table 2 summarises the main information regarding the 30 articles selected for this systematic review.

Overview of the studies

The results of the review are stratified into three different aspects: (I) methodology that covers the methodological profile of the study, that is, qualitative, quantitative or mixed; (II) a competitive profile of the coaches analysed that refers to the level of the evaluated coaches, elite or non-elite; and (III) sources of stress among sports coaches that verifies whether the stress is of psychological, physiological or psychophysiological origin.

Methodological approach

According to the results, 86.8% of the analysed studies used qualitative methods (Chroni et al., 2013; Costa et al., 2012a; Dias, Cruz & Fonseca, 2010; Drake & Hebert, 2002; Durand-Bush, Collins & Mcneill, 2012; Frey, 2007; Georgios & Nikolaos, 2012; Hendrix et al., 2000; Kelley, Eklund & Ritter-Taylor, 1999; Kellmann & Kallus, 1994; Kellmann et al., 2015; Judge et al., 2015; Knight & Harwood, 2009; Knight, Reade, Selzer & Rodgers, 2013; Levi, Nicholls, Marchant & Polman, 2009; Knigths & Ruddock-Hudson, 2016; Malinauskas, Malinauskiene & Dunciene, 2010; Olusoga et al., 2009; Olusoga et al., 2010; Olusoga, Maynard, Hays & Butt, 2012; Penteado et al., 2012; Rhind, Scott & Fletcher, 2013; Richards, Templin, Levesque-Bristol & Blankenship, 2014; Tashman et al., 2010; Thelwell et al., 2008; Thelwell et al., 2010), only 6.6% of the analysed studies used a quantitative methodological approach (Kugler et al., 1996; Loupos et al., 2005) and 6.6% used quantitative and qualitative methods concomitantly in the assessment of stress among sports coaches (Hudson et al., 2013; Loupos et al., 2004).

With regard to the quantitative methods, the measurement of physiological markers was the primary approach used to assess stress among sports coaches. Salivary cortisol, immunoglobulin A (Kugler et al., 1996; Loupos et al., 2004), plasma fibrinogen, tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) antigen (Loupos et al., 2005) and alpha-amylase (Hudson et al., 2013) were the most commonly used physiological markers. The results of the quantitative studies showed that the levels of all the investigated physiological markers of stress were significantly elevated during competitions compared with the resting state (Hudson et al., 2013; Kugler et al., 1996; Loupos et al., 2005).

Competitive profile of the analysed coaches

To classify the level of competition of the sample following Thelwell et al. (2008), the coaches who trained

professional athletes were categorised as elite coaches, whereas those who worked in amateur sports, high schools or universities and within junior categories were classified as non-elite coaches.

The results regarding the level of competition of the coaches analysed in this review showed that 43.3% of the sample corresponded to elite coaches (Dias et al., 2010; Kellmann, Altfeld and Mallett, 2015; Knigths & Ruddock-Hudson, 2016; Kugler et al., 1996; Levy et al., 2009; Loupos et al., 2005; Olusoga et al., 2009; Olusoga et al., 2010; Olusoga et al., 2012; Penteado et al., 2012; Rhind et al., 2013; Thelwell et al., 2008; Thelwell et al., 2010), another 33.3% corresponded to non-elite coaches (Drake and Hebert, 2002; Frey, 2007; Hendrix et al., 2000; Hudson et al., 2013; Kelley et al., 1999; Knight & Harwoord, 2009; Knight et al., 2013; Malinauskas et al., 2010; Richards et al., 2014; Tashman et al., 2010), and 23.4% of the studies included both elite and non-elite coaches (Chroni et al., 2013; Costa et al., 2012a; Durand-Busch et al., 2012; Georgios & Nikolaos, 2012; Judge et al., 2015; Kellmann & Kallus, 1994; Loupos et al., 2004).

Sources of stress among sports coaches

The results indicated that the coaches were affected by organisational

stressors such as social isolation (e.g., Levy et al., 2009; Olusoga et al., 2009), poor training facilities (e.g., Knight et al., 2013; Thelwell et al., 2010), the need to manage conflict (e.g., Chroni et al., 2013; Rhind et al., 2013) and interference of the athletes' relatives during training sessions and competitions (Drake & Hebert, 2002; Durand-Bush et al., 2012). With regard to performance stressors, the coaches mentioned the following: concern with their performance (e.g., Olusoga et al., 2010; Thelwell et al., 2010) and the athletes' performance (e.g., Dias et al., 2010; Frey, 2007, Thelwell et al., 2008), pressure from the media and the managers (e.g., Chroni et al., 2013; Olusoga et al., 2009), concern for the athletes' injuries (e.g., Olusoga et al., 2009; Rhind et al., 2013) and concern over the results of competitions (e.g., Hudson et al., 2013; Kugler et al., 1996).

DISCUSSION

The goal of the present study was to conduct a systematic review of stress in coaches. The results revealed that the majority of the analysed studies used qualitative methods, thus agreeing with the findings of Hudson et al., (2013). Goellner et al. (2010) observed that in addition to

being easy to apply, qualitative methods do not involve invasive procedures that might deter volunteers from participating. Such features might help explain the predominance of qualitative methods in the assessment of stress among sports coaches because these types of methods commonly use semi-structured interviews and questionnaires.

Conversely, only 6.9% of the reviewed studies used quantitative methods to assess stress among sports coaches. Physiological parameters such as salivary cortisol, immunoglobulin A, plasma fibrinogen and the tPA antigen were used for quantitative assessments of stress. Kugler et al. (1996) considered such physiological markers to be relevant instruments to assess stress because cardiovascular diseases may be associated with physiological stress responses (Stalnikowicz & Tsafrir, 2002). However, the financial costs and the procedures involved in sample collection, which are sometimes invasive, may explain the infrequent use of the aforementioned markers for the quantitative assessment of stress among sports coaches. In addition, because very little is known regarding the sensitivity of those markers in assessing stress at work among sports coaches, additional studies using physiological parameters are required to consolidate those findings. Finally, because of the small number of studies on the physiological aspects of stress among sports coaches, the results of the measurements have not yet been normalised, which hinders the comparison among coaches from different sports and levels of competition.

Only 6.9% of the studies used qualitative and quantitative methods concomitantly. Because both approaches exhibit particular advantages and disadvantages, their concomitant use is an attempt to better understand the complex process of the assessment of stress among sports coaches. In addition, according to Loupos et al. (2004), because stress is a multifactorial variable, to evaluate it more accurately, it is necessary to analyse other variables, such as anxiety.

For coaches at the competitive level, this systematic review identified that these professionals are involved with the independent labour stress that occurs at the competitive level. The results of this study indicate that coaches of both elite and non-elite athletes are affected by various sources of stress although a larger number of investigations are conducted with elite coaches. The results indicated that the sources of stress differ based on the competitive level on which the coach is working. Non-elite coaches, for example, experience different stressors than do elite trainers, such as the influences of and friction with the families of athletes in training and competitions (e.g., Durand-Bush et al., 2012; Knight & Harwood, 2009). Conversely, non-elite coaches are less affected by stress from the economic and commercial pressures of sport, the media, and leaders of the fans, who are more present in elite sports environments (Chroni et al., 2013; Rhind et al., 2013). In summary, the characteristics and types of sources of stress are directly related to the uniqueness of the environment in which a trainer is inserted because certain stress factors are quite specific to certain contexts. Understanding the particularities of the coach's work environment becomes important because it will facilitate the development specific programmes for stress management, which will benefit the health and performance of coaches.

Olusoga et al. (2009) highlighted the need to enlarge the scope of stress assessment among elite coaches to improve knowledge of the consequences of stress among professionals working in high-performance sport. However, interviewing or subjecting elite coaches to scientific studies to assess components related to their professional performance is a difficult task for researchers because of the limited time availability and limited interest of such professionals in subjecting themselves to

evaluations and scientific research procedures. In short, coaches are not aware of the relevance of this type of study to the development of their professional careers and their sport. As a rule, sports coaches view assessments as threats and criticism of their behaviour in the workplace rather than as useful tools that may contribute to their professional and personal growth.

With regard to the sources of stress, the present systematic review observed that coaches are exposed to both performance and organisational stressors. One of the primary performance stressors was the coaches' concern with the athletes' performance in training and competition settings, which they experience on a daily basis. The concern for their athletes' performance is justified because the coaches believe that the odds of keeping their jobs depend on the athletes' performance during training and competitions and on their own ability to motivate the athletes to learn and improve their performance (Gould, Greenleaf, Guinan & Chung, 2002). Thelwell et al. (2008) identified other performance stressors, including athletes' injuries, inadequate preparation, the technical level of opponents and competitions. Such performance stressors have a multifactorial

nature and are often interrelated and manifested in the course of the coaches' work, resulting in increased stress levels at work. Some researchers consider that some performance-related aspects cannot be fully controlled by coaches, such as injuries resulting from contact with an opponent, referees' mistakes, or the quality of the opponents (Chroni et al., 2013; Frey, 2007; Olusoga et al., 2009; Rhind et al., 2013). To be able to tolerate such adverse conditions, Thelwell et al. (2010) indicated that coaches ought to develop satisfactory coping and stress control strategies so that they can focus exclusively on the sources of stress that they can affect and control.

One further performance stressor detected in the present study was the concern of coaches with their own performance. This source of stress derives from the pressure for results and winning championships that coaches are exposed to regardless of the level of competition on which they work and whether the sport is individual or collective (Chroni et al., 2013; Durand-Bush et al., 2012; Frey, 2007; Levy et al., 2009; Olusoga et al., 2010; Thelwell et al., 2008). According to some studies, coaches' stress levels increase during competitions (Hudson et al., 2013; Kugler et al., 1996; Knight & Harwood, 2009; Loupos et al., 2005), and their concern with results is often because of the fear that a poor performance might cost them their jobs (Levy et al., 2009).

The media influence was mentioned as a performance stressor mainly by elite coaches but played no role in the work

environment of non-elite coaches (Drake & Hebert, 2002; Hendrix et al., 2000). The results of studies conducted with elite coaches indicated that the pressure exerted by the sports media increases the pressure on the coaches' work because coaches have no control over what is published in the media. Coaches complained that the information reported by the media is not always true and does not always reflect actual facts. One further problem mentioned by the coaches was the repercussions of the information spread by the media, which might influence the behaviour of managers, athletes and fans and increase the pressure on athletes and the technical staff (Olusoga et al., 2009; Rhind et al., 2013). In summary, performance stressors often differ depending on the performance level of the coach; however, this type of stress is present in the coach's work environment.

The results indicated that among the organisational stressors, the interference of the athletes' relatives in training sessions and competitions was one of the most relevant stressors for non-elite coaches (Drake & Hebert, 2002; Durand-Bush et al.,

2012; Knight & Harwood, 2009). Coaches who develop athletes are more likely to find themselves in such situations because parents generally follow their children's performance closely. Smoll, Cumming and

Smith (2011) observed that the influence of parents plays a crucial role in the athletic development of the children; however, parents who interfere with the coaches' actions exert a negative effect on both the coaches' and the athletes' sports performance. Thus, parents must understand what their actual role is and be aware of the adverse effects of an inappropriate attitude.

The social isolation of the profession leads to coaches having little time with family and friends, which is emphasised as a source of organizational stress (Levy et al., 2009; Olusoga et al., 2009; Rhind, et al. 2013). According to Levy et al. (2009), the frequent traveling and heavy workload reduces the time coaches need to rest. Gould et al. (2002) considered that participation in social activities with friends and family is important for coaches to control the stress caused by social isolation.

Furthermore, regarding organisational stressors, the investigated

coaches mentioned the need to manage conflict in the workplace (Olusoga et al., 2009; Levy et al., 2009; Thelwell et al., 2008; Thelwell et al., 2010). Independent of the competitive level, maintaining a conflict-free environment is necessary for athletes to exhibit a satisfactory performance (Thelwell et al., 2008). The need for coaches to manage conflict arising

among athletes in training sessions and competitions negatively affects the team's performance because coaches must shift their attention to issues other than the technical, tactical, physical and psychological aspects relevant for success.

In some studies, an inadequate training infrastructure stood out as another organisational stressor for elite and non-elite coaches (Durand-Bush, et al., 2012; Knight et al., 2013; Levy et al., 2009; Olusoga et al., 2009; Rhind, et al., 2013; Thelwell et al., 2010). Sports managers often do not consider the work conditions provided to coaches, and regardless of whether such conditions are good or bad, coaches are continuously pressed for results (Thelwell et al., 2010). Thus, coaches working in satisfactory work conditions are less susceptible to this organisational stressor.

The interference of upswings in stress in coaches was also identified. According to Kallus and Kellmann (1994), stress levels of coaches during a labour action were reflected in the behaviour of these professionals during periods off. Kellmann et al., (2015) noted that a recovery period of two weeks was beneficial for stress control in coaches. Therefore, it is up to the coaches and sports

managers to recognise the importance of recovery periods for the health of coaches and to maximize their work performance in order to attain the highest level of performance from their athletes.

Several studies reported a positive correlation between stress and burnout syndrome symptoms (Georgios & Nikolaos, 2012; Hendrix et al., 2000; Kelley et al., 1999; Malinauskas et al., 2010; Tashman et al., 2010). Thus, the results of the present review highlight the need to control chronic stress to improve the coaches' health because the studies showed that professionals who are exposed to chronic stress at work are susceptible to developing burnout syndrome symptoms.

Finally, the present study also observed that the control of stress may contribute to enhancing the coaches' physical, psychological and social wellbeing, thus maximizing the ability of

coaches to perform their work, with consequent improvement in the athletes' performance (Frey, 2007; Levy et al., 2009; Olusoga et al., 2010).

In addition to organising and systematising the available information on coaches' stress that affects their lives, one further merit of the present study was bringing into the discussion the need to achieve better control of stress and thus help these professionals who are involved with the development of children, youth and adults in elite and non-elite sports settings. The presence of emotionally balanced professionals who are able to create a healthy environment for learning and development is of paramount importance for sports institutions. As a limitation, the present study only analysed articles published in English, Spanish and Portuguese over the past 20 years; thus, other, relevant studies might have been excluded. Another limitation is that the present review analysed articles corresponding to various sports and coaches from different countries, allowing us to conclude that the stressors affecting coaches' work are multifactorial and vary according to the various contexts.

CONCLUSION

The results of the present study support the conclusion that there are differences in the types of performance and organisational stressors to which elite and non-elite coaches are exposed.

Despite such variability among studies, some common stress factors were also identified, such as the coaches' concern for their athletes' performance and their fear of losing their jobs in the event of poor athletic performance.

Additionally, the necessity to make sports managers and the scientific community aware of the relevance of assessing stress in sports coaches was identified because of the consequences of stress on the coaches' health and work performance and on the performance of their athletes.

In turn, coaches ought to be more receptive and participate in studies on this subject to advance the understanding of the stress that they are exposed to at work and that impairs their performance within and outside of the sports environment. Moreover, assessment tools specific to this population must be validated to define the 'gold standard' markers for stress assessment in elite and non-elite coaches using a three-dimensional approach that includes biological, psychological and social aspects and affords a multifactorial understanding of the negative effects of

stress on the coaches' state of health, quality of life and performance. Healthy coaches who are able to control their level of stress at work play a more efficient role in the development of athletes and sports teams.

To improve the psychological skills of sports coaches, it is necessary to develop training courses and programmes that seek to develop the psychological skills of coaches so that they can better cope with the problems they face in their professional lives.