INTRODUCTION

In the sports context, the coach has a key role in training and competition (Lara-Bercial, Mc Kenna, 2017; Zetou, Amprasi, Michalopoulou, & Aggelousis, 2011; Pesca, Szeneszi, Delben, & Raupp, 2017), with a view to the development of athletes and team (Resende, Sarmento, Falcão, Mesquita, & Fernández, 2014). In this sense the coach should base its activity in a set of knowledge and skills, so that it is developed in an effective way (Barros, et al., 2010; Mesquita, Isidro, & Rosado, 2010). The coach-athlete interaction influences the performance of the athletes (Erickson & Cété, 2015; Rezania & Gurney, 2014), team cohesion (Fiorese et al., 2017), and coaches should develop skills at the level of leadership and communication. The communication is a critical element in the coach-athlete relationship (Aly, 2014), since it can positively or negatively influence its performance (Robert, Gyöngyvér, & Attila, 2013). It is through communication that the coach issues instructions during the competition (Santos & Rodrigues, 2008), using a set of strategies that seek to influence the behavior of the players and the team (Smith, 2010). Systematic observation has been an important source of knowledge (Cushion, Armour, & Jones, 2003), allowing the analysis of the strategies used by experts' coaches (Ford, Coughian, & Williams, 2009; Morgan, Muir, & Abraham, 2014), which constitutes an important contribution to their professional development (Cushion, 2007).

According to the above, in the communication process between coach-athlete is fundamental the instruction issued by the coach, but no less important is the reception of the message. Effective communication depends on how the players process information emitted by the coaches (Januário, Rosado, Mesquita, Gallego, & Anguilar-Parra, 2016). Studies conducted have allowed to verify that a substantial part of the information sent is not retained (Januário, Rosado, Mesquita, Gallego, & Anguilar-Parra, 2016; Lima, Mesquita, Rosado, & Januário, 2007; Mesquita, Rosado, Januário, & Barroja, 2008; Rosado, Mesquita, Breia, & Januário, 2008). Studies that seek to analyze the behavior of athletes immediately after issuing instruction by the coach, find that the characteristics of the competition creates difficulties in the process of communication in the competition. This fact is illustrated in the obtained results, since they show that there is a considerable proportion of occurrences in which the athletes do not modify the behavior or modify in a manner contrary to the intended by the coach (Santos, Sequeira, & Rodrigues, 2012; Santos, Lopes, & Rodrigues, 2014; Santos, Lopes, & Rodrigues, 2016).

This research aims to go beyond observing the instructional behavior of coaches and behaviors of athletes in competition. We also intend to study the coaches' expectations above mentioned variables. Moen (2014) studied the expectations of coaches and athletes about the coach's behavior and the way these expectations affect athletes. The results of the study indicate that coaches and athletes in general believe that coaches need to be aware that their behavior affects motivation and performance of the athlete. Pina and Rodrigues (2006) conducted an investigation on the intervention of the coach of the national volleyball team in the time-outs and intervals. The authors recorded correlations between the expectation in the tactical categories (tactical service and tactical block) and the behavior in the categories of the psychological dimension (psychological-pressure-aggressiveness). The coach had the expectation of issuing tactical information, but in reality, his behavior mainly focuses on psychological aspects. Santos and Rodrigues (2006) conducted a study with 6 senior football coaches in competition, and recorded correlations between expectations and instruction behavior in the objective dimension (prescriptive and positive affectivity), in the direction dimension (group players and substitute players) and the content dimension (technical and tactical system).

According to the aforementioned we can see that communication is a crucial factor in the direction of the team in competition. The results of the presented studies show little correlation between expectations (decisions taken before the competition) and the behavior of the coach in the competition, as well as the result of his intervention in the players and team. In this perspective we can understand that coaches have no habit of preparing their intervention and think what effect it will have on athletes.

The way the coach prepares the competition can be inflating a more effective communication process. Our study intends to be a further contribution to verifying the way coaches prepares the competition and whether it has any relationship with the competing behaviors. According to the work performed by other authors, this research aims to verify the existence of relationships between coaches ' expectations and behavior in competition. However, we do not want to restrict the analysis of this relationship with the behavior of instruction, but also add the behavior of the athletes and develop the study on youth football. Thus, the aim of the study is to analyze the coaches ' expectations about their behavior in the competition and the effects they will have on the behavior of athletes, with the behavior of instruction and behavior of athletes in competition.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This study is part of an ecological research focused on the analysis of the instruction behavior of the coach and analysis behavior of the athletes in competition (Santos, Lopes, & Rodrigues, 2014; Santos, Sarmento, Louro, Lopes, and Rodrigues, 2014). To analyze the behavior in the context where they develop, not isolating from external influences, offers good opportunities for understanding (Anguera & Hernández-Mendo, 2014). The data collection is performed in the usual context of the competition, which favors the ecological validity of the research (Portell, Anguera, Hernández-Mendo, & Jonsson, 2015). According to the above and supported on observational methodology as scientific procedure (Anguera & Hernández-Mendo, 2013), we developed our study in the natural and usual context, taking into account the objectives set were coded perceptible behaviors through an observational instrument constructed for this purpose (Anguera, Blanco Villaseñor, Hernandez Mendo, & Losada, 2011). In our investigation, we intend to analyze in the context of the competition the behavior of coach's instructions in the team direction. That is, the perceived behaviors were coded, based on the observation of the coach in the usual context of the team's direction (substitute bank) in national championship games. The research has considered all ethical aspects enshrined in the Declaration of Helsinki (Harriss & Atkinson, 2013) and was approved by the Scientific Council of the University of Madeira.

Participants

Participants in the study were youth football coaches (n=4), which competed with their teams in Portugal national championship 13/14. Coaches possessed coach certification issued by the Sports Institute of Portugal and they were graduated in Physical Education and Sport. The average age of coaches was 42.5 years (SD=5.59) and had an average of years of experience in youth football coaching of 14.5 (SD=6.18). It was proposed to the coaches to participate in this investigation, taking into account that they fulfill the requirements of being licensed coaches in sports, have professional ballot, train teams of the national championship and have more than five years to perform the activity of youth coaching.

Data were collected in total playing time in two competitions by coach. They were analyzed 4151 coach's instruction behaviors, 4151 occurrences concerning attention of athletes and 1829 occurrences for the reactive motor behavior. In relation to expectations 8 questionnaires were analyzed. Each questionnaire consisted of 36 questions corresponding to the categories and subcategories of the used observation systems.

Instruments

To encode the instruction behavior of coaches in the direction of the team we used the Instruction Analysis System Competition for Football (SAIC). The coding of the behavior of athletes was conducted through the System of Observation Behavior of Athletes in Competition (SOCAC). We used to encode the behaviors the software LINCE, the Laboratory Motricity Observation, INEFC, University of Lleida (Gabin, Oleguer, Anguera, & Castañer, 2012).

The collection of data from the expectations of coaches was performed using the questionnaire on Expectations of Instruction and Behavior of Athletes in Competition. The questionnaire went through a validation process taking into account suggested by several authors (Hill & Hill, 2009; Mesquita, Isidro, & Rosado, 2010; Tuckman, 2002) (preliminary 1-study for the creation of the 1st version of the questionnaire; 2-creation of the 1st version of the questionnaire; 3-validation of the experts; 4-application pilot questionnaire (Santos, Lopes, & Rodrigues, 2013); 5-reliability of the questionnaire; 6-finale version of the questionnaire). The first part of the questionnaire is composed by 21 questions relating to the coach's expectations about your instruction behavior in the direction of the team in competition. The second part is composed by 13 questions and is relating to coach's expectations about the behavior of athletes in competition. Each question corresponds with the categories and subcategories of observation systems used in this investigation. The answer to each question was carried out through a Likert scale with five levels (Hill & Hill, 2009): 1-none, 2-little, 3-medium, 4-very, 5-quite.

Procedure

Before starting the investigation was necessary to obtain permission to conduct the study. To make this possible, we have made contact with clubs and coaches and we scheduled meetings to clarify the objectives and methodological procedures to be developed for data collection. The confidentiality of the data collected was guaranteed, having been referred to that it would only for statistical analysis. After being guaranteed acceptance to participate in research and fill in the form to characterize the sample, we give informed consent and we scheduled the two games to observe.

According to what had been agreed with all coaches we reached the stadium 90 minutes before the scheduled play time to deliver the questionnaire of expectations about the behavior of the instruction and behavior of the athletes in the competition. Each coach responded to the questionnaire in a room courtesy of the club, sitting comfortably and in a quiet and tranquil environment. During the game a camera was used to film only the coach. This camera had a sound receiver that was plugged into the wireless microphone that was placed on the lapel of the tracksuit jacket. A second camera was also used to record the game, allowing us a better interpretation of the instructions given by the coach and correctly categorizing the behavior of athletes in competition.

The data collection in each game was performed in the following sequence: 1) application of the questionnaires of expectations, 2) audio recording and images the behavior of the coach and the athletes in competition.

Reliability

The training observers and inter and intra observer reliability was performed according to the reported by Brewer and Jones (2002), procedures already used by other authors (Erickson & Côté, 2015; (Partington & Cushion, 2013). Thus we test the reliability of the data to ensure data quality (Anguera & Hernández-Mendo, 2013;Blanco-Villaseñor, Castellano, Hernández-Mendo, Sanchez-López, & usabiaga, 2014). Through the Kappa of Cohen agreement measure (Cohen, 1960) we obtained the values of reliability. The reliability values inter observers (k>.817) and intra observer (k>.841) demonstrate that there is a good consistency, stability and agreement of the observation.

Internal and external reliability of the questionnaire used in the research was carried out in order to be checked for consistency (Hill & Hill, 2009; Tuckman, 2002). The external reliability was ensured since the questions were prepared by SAIC and SOCAC (Santos & Rodrigues, 2008;Santos, Sequeira, & Rodrigues, 2012). The internal reliability was verified by equivalence of answers to two versions of the question (Hill & Hill, 2009). In this sense, we applied the questionnaire to 5 coaches not participating in the research, respecting the methodological procedures of the study. The coefficient of reliability was obtained by the correlation between the two answers of the two versions of the question. The results corresponded to strong correlations (r>0.8 and r<1.0), which demonstrates a good and excellent reliability value (Hill & Hill, 2009).

Statistical

The descriptive analysis, the normality test and the analysis of correlations between variables was performed using the computer program IBM SPSS Statistics 20®. To verify the normality, we used the Shapiro-Wilk test, recommended for n<50 (Hill & Hill, 2009). Variables were recorded with normal and non-normal distribution. In this way we used to check the correlation between the expectations and the behavior of the correlation coefficient of Pearson and Spearman. Data analysis was performed according to the suggested by Anguera and Hernández-Mendo (2015), taking into account the observational design of our investigation (punctual/nomothetic/multidimensional).

RESULTS

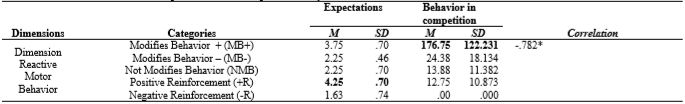

The results presented are related to the behavior of instruction, behavior of athletes and expectations of coaches. Each table of results is relative to the different dimensions of analysis. Tables included correlations between the expectations in the category/subcategory and between the categories/subcategories for a level of significance p≤0.05 and p≤0.01.

The coaches were expected to emit more positive affective instruction (M=4.38, SD=.91), however in the competition the instruction issued is predominantly prescriptive (M=387.88, SD=238.97).

In table 1 we can observe a significant inverse correlation (-.866, p≤.01) between the positive affective (AF+) and prescriptive (PRE) categories. The studied coaches had the expectation of issuing positive affective instruction, but we found that in the direction of the team in competition the instruction is predominantly prescriptive.

Table 1. Competition behavior and coaches' expectations in the objective dimensio

*Correlation is significant to a degree of probability p≤.05.

**Correlation is significant to a degree of probability p≤.01.

We also emphasize significant inverse correlation between the expectations - positive evaluation (EV+) (-.814, p≤.05), negative evaluation (EV-) (-.737, p≤.05) and the behavior of instruction in competition - positive affective (AF+). The coaches in competition preferably use the information with the objective to positively evaluate the behavior of athletes and technical and tactical execution instead of the positive affective instruction. In relation to little expectation negatively evaluate (EV-) the performance of the athletes, we found the opposite direction in the competition that coaches praised (AF+) the performance of athletes (-.737, p≤.05).

When coaches are expected to positively assess (EV +) the behavior or execution of technical-tactical athletes in competition, the behavior of instruction records a low use of the strategy of questioning the athletes and the team (INT) in its execution, situation of the game or information issued previously (-.741, p≤. 05).

The expectations of the coaches, as to the form of instruction, was to emit more auditory-visual information (Au-VIS) (M=4.13, SD=.99), however, during the competition the information emitted is fundamentally auditory (Au) (M=334, SD=236.1).

Table 2. Competition behavior and coaches' expectations in the form dimension

*Correlation is significant to a degree of probability p≤.05.

**.Correlation is significant to a degree of probability p≤.01.

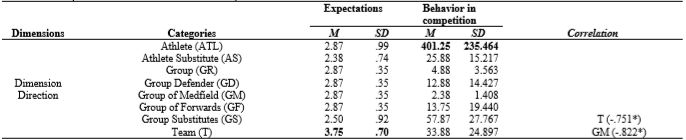

In the direction of instruction dimension (table 3), coaches issued more information to the athlete in competition (ATL) (M=401.25, SD=235.46), however their expectations focused on issuing instruction to the team (T) (M=3.75, SD=.70).

Table 3. Competition behavior and coaches' expectations in the direction dimension

*Correlation is significant to a degree of probability p≤.05

**.Correlation is significant to a degree of probability p≤.01

We observed two significant inverse correlations in this dimension of the instruction. The coaches had expectations of issuing a lot of instruction for the team (T), in the competition little information was issued in the direction of the midfield sector (GM) (-.822, p≤.05). We also think that when the expectations are for the average value of the instruction directed to the substitute group (GS) in the competition, the coach's instruction behavior is directed to the team (T) (-.751, p≤.05).

Table 4. Competition behavior and coaches' expectations in the content dimension

*Correlation is significant to a degree of probability p≤.05.

**Correlation is significant to a degree of probability p≤.01.

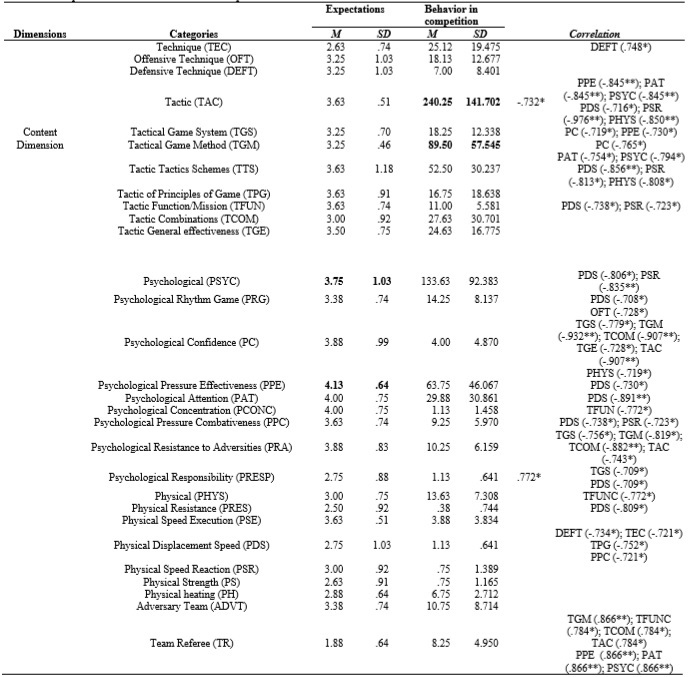

With regard to the contents of the instruction the coaches had perspective to issue more information of psychological content (PSYC) (M=3.75, SD=1.03), more specific psychological pressure for efficacy (PPE) (M=4.13, SD=.64). However, in the competition, coaches have issued more tactical instruction (TAC) (M=240.25, SD=141.70), more specifically tactical game method content (TGM) (M=89.50, SD=57.54).

In the content dimension of the education, we observed correlations between the expectations and the behavior of the coach in the subcategory psychological responsibility (PRESP) (.772; p≤.05), and a negative correlation for the tactical category (TAC) (-.732; p≤.05).

The coaches are expected to emit little information about the technical elements (TEC) performed by the players, however it was verified in the competition a preoccupation with the aspects related to the most correct execution of defensive techniques (DEFT) (.748, p≤.05). Coaches issued information with this content, especially when they intended players to perform the technique without infringing the rules.

We also noted significant correlations between expectations - the team referee (TR) category and instruction behavior - tactical category (TAC) (.784, p≤.05), psychological category (PSYC) (.866, p≤.01) and tactical game method (TGM) (.866, p≤.01), tactical function/mission (TFuN) (.784, p≤.05), tactical combinations (TCOM) (.784, p≤.05), psychological pressure effectiveness (PPE) (.866, p≤.01) and psychological attention (PAT) subcategories (.866, p≤.01). The expectation of youth players coaches to deliver little information concerning the team referee is reflected in the direction of the team in competition. The principal concerns of youth coaches were related to tactical and psychological aspects.

In relation to the expectations about the instructions with content related to various subcategories tactics and other categories of the content dimension, we observed inverse correlations, confirming that coaches when directing the team in competition attribute more emphasizing to the tactical aspects, compared to the psychological and physical aspects. However, this fact does not occur in the subcategory psychological pressure efficacy (PPE). The coaches expect to provide a great deal of information on various tactical aspects; however, they provide more information that seeks to pressure the athletes and the team, encouraging them to be more effective in solving gambling situations. This subcategory of the psychological category is the second with more occurrences in the direction of the team in competition.

The significant inverse correlations recorded between the expectations of providing information with psychological content and instruction behavior, demonstrate that, in a competitive situation, coaches are primarily concerned with the tactical aspects. We also found that coaches who have expectations of giving instruction with psychological content are those who give less information in competition with physical content.

Regarding the correlations observed between expectations - physical category, physical strength and physical displacement speed and instruction behavior, they come to prove the previously mentioned idea that the main concerns of youth player coaches focus mainly on the tactical aspects and secondly on the psychological aspects.

As for the athletes' behavior in competition, the coaches have expectations that the athletes will be very attentive (ATATL) (M=4.38, SD=.51). In competition most occurrences evidenced that the athletes were attentive (ATATL) (M=393.50, SD=231.77). In this dimension we verified a correlation between expectations and behavior in competition in the category of inattentive athlete (IATL) (.871; p≤.01) and a negative correlation in the category of attentive athletes (ATATL) (-.845; p≤.01).

Table 5. Athletes' behavior in competition and the expectations of coaches in the Attention dimension

*Correlation is significant to a degree of probability p≤.05.

**.Correlation is significant to a degree of probability p≤.01.

In the attention dimension, the behavior of the athletes in competition, we verified two significant negative correlations between the coaches ' expectations for the athlete's attention (ATL) and the behavior of the athletes observed in the competition, in the categories Athlete's substitute for attention (ATAS) and athlete's Inattention (IATL) (-.850, p≤.01).

Coaches had few expectations regarding the inattention of athletes (IATL) and group of athletes (IGR) (defenses, midfielders, forwards and substitutes) and competition there were also low values for the category attention group (ATGR) (.770, p≤.05; .772, p≤.05). The Low values for the category attention group (ATGR), due to the little instruction directed at sectors of team and group of substitutes. This situation is also observed in significant correlations between the low expectations on the team inattention (IT) and the behavior of athletes in competition in the categories attention athlete substitute (ATAS) (.750, p≤.05), attention group (ATGR) (.874, p≤.01) and inattention athlete (IATL) (.737, p≤.05). The remaining negative correlations observed are due to coaches' high expectations on team attention (ATT), and to the low values recorded for the categories attention athlete substitute (ATAS) (-.951, p≤.01) and inattention athlete (IATL) (-.729, p≤0.01). The inverse correlation between the expectations of the category attention team (ATT) and the behavior of athletes in competition (-0.945; p≤.01) was due to the high values registered in athlete attention category (ATATL).

In the reactive motor behavior dimension, we verified that coaches have expectations that athletes continue to perform actions and behaviors that are concomitantly evaluated positively (+R) (M=4.25, SD=.70). In the competition we verified that the athletes modify the behavior according to the instruction issued (MB+) (M=176.75, SD=122.23). We recorded a negative correlation in the category that modifies the behavior positively (MB+) (-.782; p≤.05).

DISCUSSION

The results show that the coaches had expectations of issuing more positive affective instruction, during the competition, which meets the previous observed by Santos and Rodrigues (2008). As we noted in the results and studies previously developed, coaches competing emit more instruction with prescriptive goal (Oliva, Miguel, Alonso, Marcos, & Calvo, 2010; Santos & Rodrigues, 2008; Santos F. J., Sequeira, Lopes, & Rodrigues, 2014; Santos, Sequeira, & Rodrigues, 2012). The observed correlations show the incongruity between expectations and what is actually verified in competition relatively to the objective of the instruction emitted. However, in the direction of the team there is the preoccupation of coaches in praising and positively evaluating the action and behavior of players (Lorenzo, Navarro, Rivilla, & Lorenzo, 2013; Pérez, Seoane, & García, 2015). Players prefer positive behaviors (Baker, Yardley, & Côté, 2003), influencing being of the athlete's performance (Robert, Gyöngyvér, & Attila, 2013) and create a motivational climate-oriented task (Marques, Nonohay, Koller, Gauer, & Cruz, 2015). Smith and Cushion (2006) found that coaches consider important the praise to increase the confidence of the players; unlike punitive instructions negatively influence the group dynamics, promote conflict intra groups, create a negative climate, promote fear of failure, are discouraging and lead to increased anxiety (Bekiari, 2014;Marques, Nonohay, Koller, Gauer, & Cruz, 2015 Nelson, et al., 2013;Smith & Smoll, 2011). In competition the coaches are preoccupation prescribing behaviors and actions to resolve the different game situations and to send information with positive evaluative and affective goal (Santos, Sarmento, Louro, Lopes, & Rodrigues, 2014). In the present study coaches said they had low expectations of emit negative evaluative instruction, which has an inverse negative correlation with the instruction behavior in competition, positive affectivity. It was observed a significant negative correlation, they found that when the coach is coach's expectations emit a lot of positive evaluative instruction, in competition was verified low instructional events such as interrogative goal. Coaches competing emit little interrogative instruction (Luján, Calpe-Gómez, Santamaria, & Burkhard, 2014;Santos & Rodrigues, 2008;Santos, Sequeira, & Rodrigues, 2012; Santos F. J., Sequeira, Lopes, & Rodrigues, 2014), sometimes using this communications strategy to see if they heard or understood the sent message (Santos, Sarmento, Louro, Lopes, & Rodrigues, 2014).

In the form of the instruction dimension, no correlations were found between the expectations and behavior. In the descriptive results we verified that the coaches have expectations to deliver more instruction in the auditory-visual form, which in competition did not happen, since the coaches issued preferably auditory instruction. Studies have shown this trend in football coaches (Ramirez & Diaz, 2004; Santos & Rodrigues, 2008; Santos, Sequeira, & Rodrigues, 2012; Santos F. J.,Sequeira, Lopes, & Rodrigues, 2014), but we can also see the concern of coaches in the information issued use along the gestural and verbal communication. During the competition the coaches of collective sports prefer to use verbal communication (Aly, 2014), however Capitanio (2003) states that the mixed communication (verbal/gestural) reinforces the impact of the message and facilitates its reception.

Regarding the direction of the instruction we found two significant inverse correlations. This happens because when coaches have expectations of provide an average amount of instruction to the group of substitutes and more instruction to the team, it was found that, in the competition, the information is directed to the team and group, respectively. The coaches of youth football players reported that before the competition it is expected to provide a lot of information to the team, which does not occur in competition. During the game the coaches gave instructions predominantly directed to the athlete, and information directed to the team obtained low values. The preference for giving directed instruction toward the athletes in competition has been registered in several investigations carried out in the modality of football (Oliva, Miguel, Alonso, Marcos, & Calvo, 2010; Ramírez & Díaz, 2004; Santos & Rodrigues, 2008; Santos, Sequeira, & Rodrigues, 2012; Santos F. J., Sequeira, Lopes, & Rodrigues, 2014).

In the dimension of instruction content coaches said they had expectations from issuing more information with psychological content, however in competition tactics are the issues that most concern the coaches. Registered correlations will meet the said. To point out that the level of expectations and instructional behavior in competition with tactical information and psychological content was the content with more occurrences. A study conducted in football has shown that the content of instruction issued on competition predominately tactic followed by the psychological content (Ramírez & Díaz, 2004; Santos & Rodrigues, 2008; Santos, Sequeira, & Rodrigues, 2012; Santos F. J., Sequeira, Lopes, & Rodrigues, 2014).Santos, Sarmento, Louro, Lopes and Rodrigues (2014)record T-patterns of instructional behaviors in the direction of teams in competition, in which coaches prescribe tactics and psychological solutions. However, a study on youth football found a predominance of psychological content of instruction issue (Oliva, Miguel, Alonso, Marcos, & Calvo, 2010). Lorenzo et al. (2013) also found with basketball coaches issuing more information with psychological content during the competition. Santos, Sequeira and Rodrigues (2012) noted with young coaches a large number of occurrences for psychological content of instruction in which the coach seeks pressure on athletes to greater effectiveness in the resolution of game situations. A significant negative correlation recorded in the tactic category meets the above mentioned. Coaches have lower expectations of issuing tactical instruction content of what actually happens in competition. Studies point to the importance given by coaches in the direction of the teams in competition for topics related to tactical aspects (Moreno, et al., 2005; Sarmento, Pereira, Campaniço, Anguera, & Leitão, 2013). It is important the coach have a thorough knowledge of the game (Jones, Armour, & Potrac, 2003) so you can at the right time to make good tactic decisions order so that they can be achieved strategic goals set before the competition (Kaya, 2014). The game of football is a complex and dynamic environment (Sampaio & Maçãs, 2012), where the ability to observe and match analysis is very important (Malta & Travassos, 2014). The coach is essential to prepare the observation (Piltz, 2003) so you can extract the game relevant information and thus deliver quality and relevant instruction to help players and staff to be more effective than opponents.

The correlation between the expectations of issuing information on the referee team and competing instruction behavior, reinforce the main concerns of the of young player coaches, focused on the tactical and psychological issues.

The expectations of issuing information with technical content are consubstantiated during the competition especially with the instruction issue with the content on the defensive technique. Coaches in competition sometimes warn their players so that when in disarm no fouls should be committed.

In the attentive dimension, we found out that the expectations of coaches are confirmed during the course of the competition, taking into account that the athletes and the team proved to be attentive to the coach and to the game. Although we observed a significant inverse correlation in the attention category, this is due to the fact that the expectations of the coaches are lower than what actually occurs in competition. However, when we analyze the significant inverse correlation between the expectations about the attention and the behavior of the athlete - athlete inattention, we noticed that when the coaches expect the player to be attentive, we verified low levels of inattention in a competition situation. It is also important to note that the low expectations of the coaches regarding athlete's inattention are confirmed in competition. The observed correlations are in line with that recorded in training (Richheimer & Rodrigues, 2000) and in competition (Santos, Lopes, & Rodrigues, 2014; Santos, Sequeira, & Rodrigues, 2012).

Regarding the behavior of reactive motor of the athletes, the coaches' expectations confirm that the players modify their behavior according to the information provided and continue to perform the behavior and technical-tactical action previously positively valued. In fact, the behavior of competing athletes demonstrates that they modify positively their behavior. We also found that the expectations value for the category of positive reinforcement is not consistent with the one observed in the game. Studies conducted in football with young players also stated that players positively modify their behavior in most of the game moments (Santos, Sequeira, & Rodrigues, 2012;Santos, Lopes, & Rodrigues, 2014). Despite the comments previously mentioned we were only able to register a correlation between the expectations and the behavior of athletes in competition - positively modifying behavior category. Coaches have lower expectations towards this behavior than what is effectively confirmed in a competition situation. The referred coaches having low expectations for the athletes change their behavior contrary to the instruction issued, or do not change the behavior; however, in competition we observe significant values for this category. Studies about retention process of information have shown that a substantial part of the instruction emitted by the coach is not retained (Lima, Mesquita, Rosado, & Januário, 2007; Januário, Rosado, Mesquita, Gallego, & Anguilar-Parra, 2016; Mesquita, Sobrinho, Rosado, Pereira, & Milistetd, 2008; Rosado, Mesquita, Breia, & Januário, 2008). Thus, we may say, in comparison verified in training (Richheimer & Rodrigues, 2000), the characteristic of the competition seems to bring trouble to the communication process established between coach and athlete.

Studies have been developed in order to assess what are the expectations of the coaches about the instruction behavior in competition (Pina & Rodrigues, 2006; Santos & Rodrigues, 2006; Santos & Rodrigues, 2008). The interaction coach athlete should be subject to a series of decisions before the competition, in terms of strategies, and to think that will be reflected in the behavior of athletes (Januário, Rosado, Mesquita, Gallego, & Anguilar-Parra, 2016; Moen, 2014). Reflective activities are extremely important for the professional development of coaches (Araya, Bennie, & O'Connor, 2015; Cushion, Armour, & Jones, 2003; Cushion, et al., 2010). These reflections are influencing decisions and expectations that coaches have on the communication process in competition, which are influencing the way the coach directs the team in competition (Cloes, Bavier, & Piéron, 2001; Debanne & Fontayne, 2009; Moreno & Alvarez, 2004). The incongruity observed in our study between the expectations and the instruction and behavior of athletes reveal some inconsistency between cognitive preparation of the coach and what is found in competition. We believe that is one of the aspects that the coach formation can contribute by providing skills and technicians related to competition preparation skills in order to increase the effectiveness of its action in the competition and in this way contribute to the athletes and team to be able to express its full potential. Thus, we think it is important to develop this research topic in different contexts, in a longer period of time (Anguera & Hernández-Mendo, 2013), promoting the training of the coach through the intervention of a coach and verifying the evolution taking into account the pre-intervention, intervention and post-intervention (Romero, Baidez, & Chirivella, 2018; Vaamonde, 2018), in order to ensure greater effectiveness of the coach activity, improving the preparation of the competition.

CONCLUSIONS

This research aims to study the coaches' expectations in instructional behavior and the athlete's behavior in competition, as well as analyze such behavior in competition. The coaches indicated they had expectations to deliver more positive affective instruction auditory-visual, directed the team and psychological content. They had still expectations of athletes are attentive and continue to execute an action or behavior that was previously valued positively.

Coaches during the competition issued preferably prescriptive information, auditory, directed the athlete and tactical content. Athletes proved to be attentive and modified the behavior positively.

We verified two significant positive correlations between what the coaches expect and what actually happens during the competition, in the content dimension (psychological responsibility subcategory) and in the attention dimension (inattention athlete category). The number of significant negative correlations registered show that what the coaches often expect does not occur in competition, or that whenever they have certain expectations on a particular behavior it happens in a different frequency than what they had expected.

This study is a contribution to the research of cognitive variables, evidencing the need for further research in different contexts, in a temporal continuity, which can provide a number of important knowledges for the preparation and training of coaches.

PRACTICE APPLICATIONS

The results obtained in our investigation provide a clear vision related to relationship between the coaches ' expectations and the instruction behaviors and athletes in competition. It seems to be emphasized that coaches do not have the habit of preparing their intervention for the competition moment. Given the complexity of directing the team in the competition, it is essential for coaches to make pre-interactive decisions, so that their intervention is clearly, concisely and specific, with the aim of making their communication process more effective. We consider it fundamental in the training of coaches, coach the coach, to prepare their intervention, also being important at the end of the competition he reflection process. This last will influence future pre-competition decisions.