INTRODUCTION

Demographic aging and the subsequent increase on the prevalence of multimorbidity currently pose significant challenges for therapeutic management. An ever increasing number of individuals over 50 years old live with multiple chronic diseases and take several concomitant drugs1. Polypharmacy can be defined as the simultaneous taking of 5 or more medications2, and can be either appropriate, when medicines use is optimized considering the patient's multiple morbidities and according to the best evidence, or inappropriate1. Not adequate polypharmacy is associated with several adverse drug events, including mortality, falls, adverse reactions, increased length of stay in hospital and readmission to hospital soon after discharge3,4,5,6.

In a cross-sectional study from 2015 conducted in Family Health Unit Rainha D. Amélia, in Oporto, Portugal, a sample of 747 patients over 64 years old was analyzed. The results showed that polypharmacy was present in 59.2% of the population, and 37.0% of them were taking potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs)7.

European Union has identified as a key priority the reduction of avoidable harm in healthcare. It is estimated that up to 11% of all hospital admissions are due to adverse drug events1. In order to prevent these adverse events, it is crucial to consider the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes that the elderly are subjected to, in the moment of prescribing. These changes often translate in an increased sensitivity to adverse effects of several drugs, or in a reduction of their responsiveness8. With aging, there is also a reduction in hepatic metabolism and renal function, a decrease in the distribution volume of hydrophilic drugs and an increase in the distribution volume of lipophilic drugs, which may be relevant in drugs such as vancomycin, amiodarone, diazepam, flurazepam and digoxin8. Moreover, the majority of clinical trials on drug safety are also conducted in young healthy subjects with a single medical condition receiving few or no other drugs8. Consequently, therapeutic management in the elderly assumes a particular relevance and requires special care.

For all these reasons, a relatively well-tolerated drug in a young individual may be considered potentially inappropriate in an older adult. A potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) is a drug whose risks of adverse reactions outweigh the clinical benefits in an elderly patient, particularly when there is a safer and more effective alternative for the same medical condition9,10. In the last few years, there have been developed several reconciliation tools that aid in the identification of PIMs.

The Beers Criteria9 is the reconciliation tool most frequently applied and widely published in the literature. They were originally developed in America in 1991, and have been updated ever since. This tool includes a table with potentially inappropriate medications (regardless of dose, duration of treatment or clinical condition); a list of drugs that may exacerbate certain diseases or clinical syndromes; drugs that should be used with caution in the elderly; and a list of drug interactions and other drugs that should be avoided in the elderly or whose dose should be reduced accordingly to the patient's renal function.

The European Union PIM List11 is a screening tool which was developed with the participation of experts from seven European countries, that allows identification and comparison of PIM prescribing patterns for older people across European countries. The EU PIM List took several international PIM lists into consideration (i.e. the German PRISCUS list12, the American Beers Criteria13,14, the Canadian List15 and the French list16), as well as further drugs suggested by experts.

Several studies have shown the importance of applying these reconciliation tools in clinical practice, as well as their impact on the reduction of the number of adverse drug events, on the improvement of the patient's quality of life and on the promotion of responsible medicines use4,17. A recent study assessed the changes in the number of prescribed medications between admission to and discharge from a geriatric ward, having concluded that geriatric hospitalization results more often in deprescribing rather than in prescribing new medications18.

Inappropriate polypharmacy and therapeutic compliance in elderly patients is one of the most important public health challenges1. Polypharmacy management involves complex decision making, and requires the combined knowledge of a multidisciplinary team, including medical doctors, pharmacists and nurses.

The objective of this study is to quantitatively assess the prescription pattern of PIMs in different inward clinical services of University Hospital Center of Cova da Beira (CHUCB), in order to identify common PIMs, to minimize the risk of adverse effects and other drug-related problems and ultimately, to promote awareness campaigns directed to multidisciplinary teams and posteriorly assess the impact of this intervention.

METHODS

This article consists in a retrospective study aiming at quantitatively assessing the prescription pattern of PIMs in selected clinical services of CHUCB, namely Medicine 1, Medicine 2, Cardiology and Pneumology.

A preliminary search was performed in the hospital's computerized system database to assess the ratio of older patients (65 years old or more) vs. the total of patients admitted in several inward clinical services of the hospital, in order to select the clinical services with a higher ratio of older patients that would motivate the pharmacists' intervention.

Afterwards, the hospital's computerized system database was searched for every patient admitted in the clinical services of Cardiology, Medicine 1, Medicine 2 and Pneumology, from January 1st to June 30th 2018. Patients less than 65 years old were excluded. Data regarding the patients' hospital ID number, their age, prescribed drugs during admission, prescribed dose, frequency, medications' start date and their respective end date were anonymously collected. Each patient was given an alphanumeric code number. The patients' medications prescribed during the admission period were assessed, and the PIMs were identified according to Beers Criteria 2015.

A descriptive statistical analysis was conducted. The average patient age and the respective standard deviation, total of patients admitted in the selected clinical services, average number of PIMs prescribed and relative percentages were calculated. The therapeutic drug classes of PIMs were identified. The analysis was conducted using the Microsoft Excel® tool.

This study was approved by the Ethics for Health Commission of University Hospital Center of Cova da Beira (study number 69/2018).

RESULTS

From January 1st to June 30th 2018, the clinical services with higher ratio of elderly patients admitted were the Medicine 2 (86.7%), Medicine 1 (86.5%), Cardiology (83.6%) and Pneumology (68.8%) services (Table 1). Medicine 2 was the service with the highest number of patients admitted during the first semester of 2018, followed by Cardiology, Medicine 1 and Pneumology (Table 1).

Table 1. Number of older patients (≥65 years old) admitted vs. the total of patients admitted in different services from January 1st to June 30th 2018

Table 2 includes the statistical data relative to each clinical service included in this study. The average age of the older patients (≥65 years old) admitted in these clinical services was approximately 81 years old. The percentage of older patients with, at least, one PIM prescribed during the inpatient period was highest in Medicine 1 (72.6%) and lowest in Cardiology (64.5%). The clinical service which had a higher percentage of prescribed PIMs was Cardiology, with 9.2% of the total of medicines prescribed being PIMs, followed by Medicine 2 (8.3%), Medicine 1 (7.7%) and Pneumology (6.7%).

Table 2. Statistical data regarding each clinical service, during the period from January 1st to June 30th 2018

Figure 1 represents the number of prescribed PIMs per patient in the clinical services mentioned above, during the inpatient period. Medicine 2 was the clinical service with the highest number of prescribed PIMs (n=9) during the inpatient period. There were 174 patients with only one PIM in Medicine 2.

Figure 1. Number of potentially inappropriate medications prescribed per patient, during the inpatient period, in the services of Medicine 2, Medicine 1, Cardiology and Pneumology. PIMs: Potentially Inappropriate Medications

Table 3 represents the therapeutic drug classes of PIMs prescribed in the services of Medicine 2, Medicine 1, Cardiology and Pneumology. The benzodiazepines were the most prescribed potentially inappropriate therapeutic drug class (PITDC) in all services included in this study, accounting for 29.97% in Medicine 2, 39.96% in Cardiology, 30.21% in Medicine 1 and 41.10% in Pneumology of the total of prescribed PIMs. The first- and second-generation antipsychotics were the next most prescribed PTIDCs in the services of Medicine 1 and Medicine 2. Intestinal motility modifiers, namely metoclopramide, also had a significant expression in Medicine 2 (12.87%), Medicine 1 (11.96%) and Pneumology (11.66%).

Table 3. Therapeutic drug classes of potentially inappropriate medications prescribed in the services of Medicine 2, Medicine 1, Cardiology and Pneumology, and the respective relative percentages, from January 1st to June 30th 2018. Most frequently prescribed therapeutic drug classes are represented in bold

Meanwhile, in the Cardiology service, the antiarrythmics, specifically amiodarone, were the second most prescribed PTIDC, accounting for 18.83% (n=106) of the total of prescribed PIMs. Amiodarone is considered a PIM in the Beers Criteria9 when used as first line therapy for atrial fibrillation, unless the patient has heart failure or substantial left ventricular hypertrophy. Nevertheless, given the design of the study, since we did not know the patient's diagnosis, we cannot assess whether the drug is potentially inappropriate.

Regarding the prescription of non-selective NSAIDs, the Beers Criteria9 recommend avoiding their use, unless other alternatives are not effective and patient can take a gastroprotective agent. After the analysis of the prescriptions, we concluded that the majority of the patients with NSAIDs prescriptions were taking a PPI simultaneously. The Others category included prescriptions of megestrol, spironolactone >25 mg per day and desmopressin, all considered potentially inappropriate by the Beers Criteria9.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are considered PIMs by the Beers Criteria if used for periods longer than 8 weeks, in non-high-risk patients9. The analysis of the inpatient prescriptions, during the first semester of 2018, retrieved only two results of a PPI (pantoprazole) prescribed for more than 8 weeks, one prescription in the service of Medicine 1 and the other in Pneumology (Table 3). However, given the nature of the data retrieved, we do not know if this was, or not, a high-risk patient, or whether the clinical condition of the patient justified the prolonged use of the PPI.

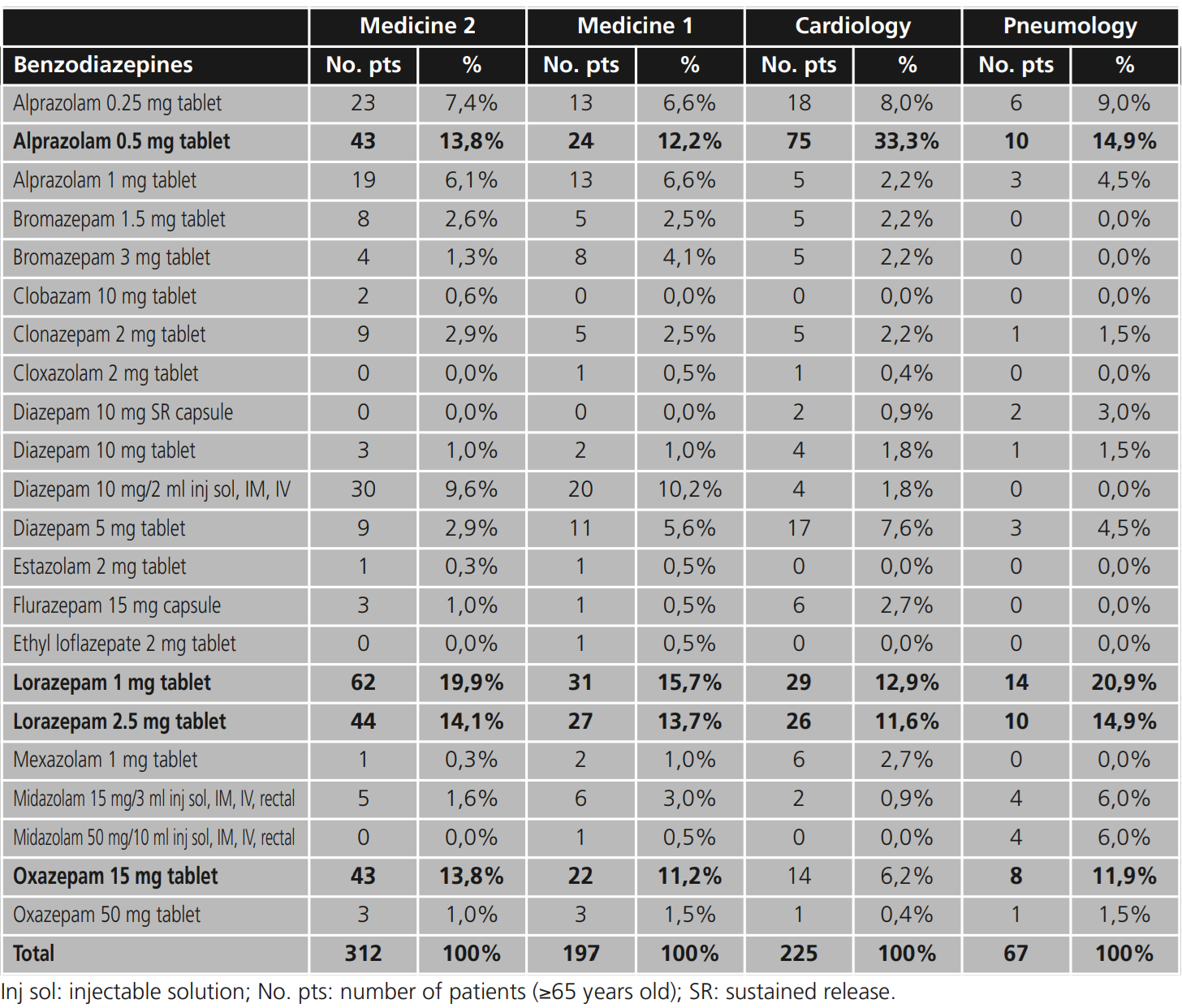

Table 4 represents the benzodiazepines prescribed by active substance, dosage and pharmaceutical form, and their respective relative percentages, in the services of Medicine 2, Medicine 1, Cardiology and Pneumology. In Medicine 1, Medicine 2 and Pneumology, lorazepam 1 mg and lorazepam 2.5 mg were the most frequently prescribed benzodiazepines, followed by alprazolam 0.5 mg. In the service of Cardiology, alprazolam 0.5 mg was the most frequently prescribed benzodiazepine, accounting for 33.3% of all benzodiazepines.

Table 4. Benzodiazepines prescribed by active substance, dosage and pharmaceutical form, in the services of Medicine 2, Medicine 1, Cardiology and Pneumology, and the respective relative percentages, from January 1st to June 30th 2018. Most frequently prescribed benzodiazepines are represented in bold

Table 5 represents the antipsychotics by active substance, dosage and pharmaceutical form prescribed in the services of Medicine 2, Medicine 1, Cardiology and Pneumology. The most frequently prescribed antipsychotic in all services was injectable haloperidol, accounting for 42.6% of the total of prescribed antipsychotics in the service of Medicine 1. Quetiapine 25 mg was the second most prescribed antipsychotic in all services studied, accounting for 25.6% of all antipsychotics prescribed in Cardiology, 23.4% in Medicine 1, 21.7% in Medicine 2 and 19.4% in Pneumology.

Table 5. Antipsychotics by active substance, dosage and pharmaceutical form, and the respective relative percentages, prescribed in the services of Medicine 2, Medicine 1, Cardiology and Pneumology, from January 1st to June 30th 2018. Most frequently prescribed antipsychotics are represented in bold Med

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to quantitatively assess the prescription pattern of PIMs in different clinical services of the hospital, namely Medicine 1, Medicine 2, Cardiology and Pneumology. It is evident by the analysis of the obtained data that benzodiazepines were the most frequently prescribed PITDC in the four clinical services studied.

Benzodiazepines have been widely used in the treatment of sleep and anxiety disorders19. However, among older individuals, long-term use of benzodiazepines is associated with significant adverse effects, including impaired cognitive function, reduced mobility and driving skills, balance issues, increased risk of falls and fractures, drowsiness and memory disorders, and might also lead to psychological and physical dependence19,20. Furthermore, new evidence suggests that the efficacy of benzodiazepines for insomnia can diminish in as little as 4 weeks, while the adverse effects might persist21.

According to Beers Criteria all benzodiazepines are considered PIMs, regardless of dose and duration of action9. However, in the EU PIM List11, lorazepam and oxazepam are not considered potentially inappropriate if prescribed in doses inferior to 1 mg a day and 60 mg a day, respectively. Furthermore, the EU PIM List even suggests both drugs, as long as the previously mentioned doses are not exceeded, as safer alternatives when compared to other drugs from the same therapeutic class.

Cardiology was the clinical service with higher percentage of prescribed PIMs when compared with the total of prescribed medicines (9.2%). However, 18.83% of the PIMs prescribed corresponded to amiodarone (Table 3), which is considered potentially inappropriate when used as first line therapy for atrial fibrillation, unless the patient has heart failure or substantial left ventricular hypertrophy9. Given the nature of the study, it was not possible to assess whether the drug is, in fact, potentially inappropriate, which may have led to an overestimation of the results.

Antipsychotics, both first and second generation, were another PITDC frequently prescribed in these services. Antipsychotics should be avoided for treatment of behavioral problems of dementia or delirium, due to being highly anticholinergic drugs, and being associated with a higher risk of cognitive impairment, stroke and mortality9,22.

These are examples of therapeutic drug classes that are often prescribed in older people and that in some cases may be causing harm or no longer providing benefit. In developed countries, it is estimated that 30% of patients aged 65 years or older are prescribed 5 or more drugs23, a clear indicator of polypharmacy, which is associated with several adverse drug events3,4,5,6. This evidence of the adverse effects of polypharmacy in older adults indirectly supports the need for deprescribing in this population24,25.

Deprescribing can be defined as the planned and supervised process of dose reduction or stopping of medication that might be causing harm or no longer providing benefit20. Scott et al.26 proposed a deprescribing protocol composed by 5 simple steps: 1) ascertain all drugs the patient is taking at the moment and the reasons for each one; 2) consider overall risk of drug-induced harm in individual patients in determining the required intensity of deprescribing intervention; 3) assess each drug for its eligibility to be discontinued (for example, no valid indication, part of a prescribing cascade, etc.); 4) prioritize drugs for discontinuation; and finally, 5) implement and monitor drug discontinuation regimen26.

This study has some limitations that must be considered, and the results obtained must be cautiously interpreted. First, given the retrospective design of the study, it is not possible to assess the context in which a certain PIM was prescribed, since we did not have any knowledge of the patients' diagnosis, clinical conditions or comorbidities. Consequently, this may have led to an overestimation of the percentage of PIMs prescribed in each service. Second, the severity of the PIM was not analyzed or determined, and neither did the clinical outcomes of the patients. Finally, PIM identification was performed using only the Beers Criteria (2015), given that it was the reconciliation tool which was more appropriate considering the nature of the study, since it indicated PIMs regardless of dose, duration of treatment and clinical condition. However, there are several other similar prescription tools in the literature that can and should be used to complement one another, for instance, the European Union PIM List11 and the STOPP/START Criteria27.

CONCLUSIONS

Inappropriate drug use and its associated harm is a growing issue among older patients. Therapeutic reconciliation has been recognized as a major intervention tackling the burden of medication discrepancies and subsequent patient harm at care transitions. Reconciliation tools such as the Beers Criteria are useful to identify inappropriate prescribing during the pharmaceutical validation of prescription. Further studies will provide more insight into the impact of the pharmacist's intervention.