INTRODUCTION

Cancer is the leading cause of disease burden in Australia.1Bowel cancer and breast cancer are among the most common cancers estimated to account for 12.4% and 13.0% of all new cancers diagnosed in Australia in 2017.2,3Bowel cancer and breast cancer are associated with a significant risk of mortality estimated to account for 8.6% and 6.5% of all age-standardised cancer-related mortality in Australia in 2017.4

In Australia, the national screening programs for bowel cancer and breast cancer are operated by the federal government’s National Bowel Cancer Screening and BreastScreen Australia programs in partnership with state and territory governments. The programs aim to deliver “an organised, systematic and integrated process of testing for signs of cancer or pre-cancerous conditions in asymptomatic populations” to enable earlier detection and improved survivability.1The programs are provided free-of-cost every 2 years to populations where evidence suggests screening is most effective at reducing cancer-related morbidity and mortality.1For bowel screening, immunochemical faecal occult blood tests are offered to people aged 50 to 74 years.1,5For breast screening, a mammogram is recommended to women aged 50 to 74 years.1,6Women over 40 years of age are also eligible.

Research suggests Australia’s national bowel cancer and breast cancer screening programs are highly effective. A major evaluation of the BreastScreen Australia program showed the program reduces breast cancer mortality by up to 28%.7Participants in the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program found to have bowel cancer are likely to have less-advanced cancer than non-participants at the time of diagnosis and a greater chance of survival.8The National Bowel Cancer Screening and BreastScreen Australia programs are well accepted by consumers, accessible and cost-effective.7 8-9Despite this, participation is moderate. In the two-year period, 2014 to 2015, 39% of eligible people completed a screening test for bowel cancer, and 54% of women in the target age group (50 to 74 years) completed a screening test (mammogram) for breast cancer.1It is therefore important to find novel ways of promoting and improving participation in bowel cancer and breast cancer screening.

Community pharmacies are one setting where cancer screening may be effectively promoted. In Australia, under the Quality Care Pharmacy Program, community pharmacies are required to deliver health promotion activities. There are more than 5300 community pharmacies in Australia, and this number is increasing.10Pharmacies are the most visited healthcare service in Australia; 94% of Australian adults use a pharmacy each year. This accounts for 300 million patient visits annually.10An estimated 3.9 million consumers attend a pharmacy each year specifically to ask for health advice.10Pharmacies may be effective at engaging hard-to-reach groups, including lower-socioeconomic groups, who may be at increased risk of cancer but less likely to participate in screening.

Most pharmacies in Australia are actively involved in some form of health promotion. For example, national health promotion programs for alcohol awareness, sexual health, smoking cessation, weight loss and continence care.11Recent research demonstrates the effectiveness and acceptability of health promotion programs in Australian pharmacies for screening for alcohol consumption12, cardiovascular disease13, chlamydia14, diabetes15,16and hypertension.17

There is available research about health promotion for cancer and cancer screening in pharmacies. Studies by Jiwaet al.18,19,20suggest pharmacists in Australia have an important role in the promotion of screening for bowel cancer. A systematic review, which included two studies by Jiwaet al.18,20and nine other studies from international settings concluded pharmacies have “significant potential” for the delivery of health promotion for the early detection ofb cancer, including promotion of screening for bowel and breast cancer.21

Australia’s pharmacies are involved in the national cancer screening programs, in particular, for bowel cancer. Community pharmacies can promote the national bowel cancer screening program by selling screening kits to those who fall outside the program’s eligibility criteria for free testing.22Recently, there has been a small pilot project involving the promotion of breast cancer screening services in community pharmacies.23However, involvement in these programs is at the discretion of individual pharmacies. This lack of consistency in service provision, and the potential for confusion among consumers, is problematic.

Overall, there is paucity of research - generally, and from Australia specifically - about key stakeholders’ perceptions of the feasibility of promoting bowel cancer and breast cancer screening in community pharmacies. Subsequently, there is a lack of evidence to inform programs for promoting cancer screening in pharmacies. This mixed-methods study with community pharmacists and key informants in the Metro South Health (MSH) region of Brisbane, Australia seeks to address this gap in knowledge. This paper reports findings related to community pharmacists’ perceptions of their role, knowledge and confidence in relation to bowel cancer and breast cancer screening health promotion. Other findings are reported elsewhere.

METHODS

This mixed-methods study was conducted in two parts. In Part 1, quantitative data was collected from pharmacists via an electronic survey. In Part 2, qualitative data was collected from community pharmacists and key informants via in-depth interviews. This paper reports on data collected from community pharmacists in Part 1 and Part 2.

Part 1 of this study was an electronic survey (see online Appendix). The survey was advertised to all pharmacists registered with the Queensland branch of the Pharmacy Guild of Australia via (1) group emails (including one initial and one follow-up email) and (2) posts on a social media channel. Community pharmacists were requested to complete the survey via an electronic link to the web host. The survey was open for 3 months between July and September 2016.

The survey consisted of multiple-choice questions. The survey began with demographic questions and asked community pharmacists about (1) perceptions of their health promotion role, (2) confidence in their health promotion role and (3) knowledge about bowel cancer and breast cancer. These questions were answered using Likert scales (e.g. 1=strongly agree to 5=strongly disagree, 1=poor confidence to 5=excellent confidence, etc.) and drop-down menus (e.g. true - false - unsure, etc.). Knowledge questions related to the key risk reduction, screening and early detection messages of the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program and BreastScreen Australia Program. The survey was delivered by email to all pharmacies registered with the Pharmacy Guild of Australia’s Queensland branch (approximately 255 pharmacies, or 85% of all pharmacies in the MSH region).

Part 2 of the study involved in-depth interviews with community pharmacists and key informants from the MSH region of Brisbane. This paper reports the findings from community pharmacists only. Other findings are reported elsewhere. A purposeful sample of community pharmacists was recruited through an expression of interest at the end of the survey. The only criteria required to participate in an in-depth interview was the identification as a community pharmacist. Sampling was not based on answers to the electronic survey. All survey respondents were community pharmacists. Those who were interested in participating in an in-depth interview provided contact details. Other community pharmacists were purposefully recruited through the researchers’ professional networks. All community pharmacists were provided with additional information by telephone or email. If a community pharmacist wished to proceed, a convenient time and date were arranged. All interviews were conducted face-to-face by the same experienced qualitative researcher in a public space such as a café or the participant’s pharmacy. Written informed consent was obtained from participants prior to commencement. The interviews lasted 45 to 90 minutes and were audio-recorded and transcribed with the participants’ consent.

Interviews built on the electronic survey to add a rich and contextualised understanding to the quantitative data. The interviews included questions exploring pharmacists’ perceptions of their role, confidence and knowledge in relation to health promotion generally, and the promotion of cancer screening specifically. The interviews investigated topics related to health promotion and cancer screening raised by the participants during the discussions.

To participate in the survey or an interview for the data reported in this paper, participants were: (1) currently registered as a pharmacist with the Pharmacy Board of Australia, (2) practicing as a community pharmacist (and not as a hospital, clinical or online pharmacist), and (3) practicing in the MSH region. MSH is a health catchment of Brisbane with approximately 1 million people, which is 23% of the Queensland population.24This catchment was selected because improving the provision of health services is a priority for the project’s funders.

Quantitative data was analysed in Microsoft Excel®. The analysis involved counts and proportions. The data were tabulated and represented graphically.

Qualitative data was analysed thematically in two phases: (1) deductively to answer the research question posed for study (What are pharmacists’ current knowledge, self-efficacy and capacity in discussing and promoting bowel cancer and breast cancer screening with their consumers?), and (2) inductively to examine the contextual data related to the research topic. The data analysis was undertaken following the iterative process outlined by Green and Thorogood.25The interviews were transcribed and read and re-read to develop familiarisation with the data. Next, significant statements in the transcripts - 128 in total - were identified and allocated a code. These statements were grouped with other similarly-coded statements to form themes - distinct, significant concepts related to the research topic. A detailed data analysis log was maintained.

The data analysis was undertaken iteratively over several months until the data settled. One researcher transcribed each in-depth interview. This researcher led the analysis of the in-depth interview transcripts with the support of two other researchers. An inter-rater reliability check was conducted with a random sample of 33 statements (approximately 25% of the data) selected from across all transcripts. The authors achieved 91% agreement about the theme to which each statement belonged and discussed the remaining 9% of statements until a consensus was reached. For this paper, the authors were in total (100%) agreement about the statements selected as evidence for each theme.

This research was undertaken collaboratively by practitioners and researchers from MSH (BreastScreen Queensland Brisbane Southside Service and National Bowel Cancer Screening Program) and the Queensland University of Technology’s School of Public Health and Social Work. The research was supported under the PAH Centres for Health Research and PA Research Support Scheme and was funded through a 2016 Small Grant from the MSH Study, Education and Research Trust Account. Ethical approval for this research was obtained from the MSH Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/16/QPAC/123).

RESULTS

The electronic survey was completed by 27 pharmacists (13 males, 14 females). SeeTable 1. Almost half (48%) of the respondents were aged 20-29 years and most (89%) had an undergraduate degree. Community pharmacists had been practicing for <1 year (11%), 1-5 years (33%), 6-15 years (18%), or over 21 years (38%). Five community pharmacists participated in an in-depth interview. This paper presents the findings from three themes, which emerged from this data: (1) pharmacists’ perceptions of their health promotion role, (2) pharmacists’ descriptions of their current health promotion role and (3) pharmacists’ knowledge and confidence in their health promotion role. These themes relate to community pharmacists’ perceptions of their health promotion role generally, and to their role in promoting bowel cancer and breast cancer screening specifically.

Table 1. Demographic information for pharmacists (n=27) who completed electronic survey.

| Gender | ||

| Male | 48% | (n=13) |

| Female | 52% | (n=14) |

| Age | ||

| 20-29 years | 48% | (n=13) |

| 30-39 years | 15% | (n=4) |

| 40-49 years | 15% | (n=4) |

| 50-59 years | 18% | (n=5) |

| 60-69 years | 4% | (n=1) |

| >70 years | ||

| Qualification | ||

| Non-tertiary qualification | 4% | (n=1) |

| Undergraduate degree | 89% | (n=24) |

| Postgraduate qualification | 15% | (n=4) |

| No response | 7% | (n=2) |

| Length of time practicing as a pharmacist | ||

| <1 year | 11% | (n=3) |

| 1-5 years | 33% | (n=9) |

| 6-10 years | 11% | (n=3) |

| 11-15 years | 7% | (n=2) |

| 21-25 years | 19% | (n=5) |

| >25 years | 19% | (n=5) |

THEME 1: Community pharmacists’ perceptions of their health promotion roles: “That’s what they’re there for”.

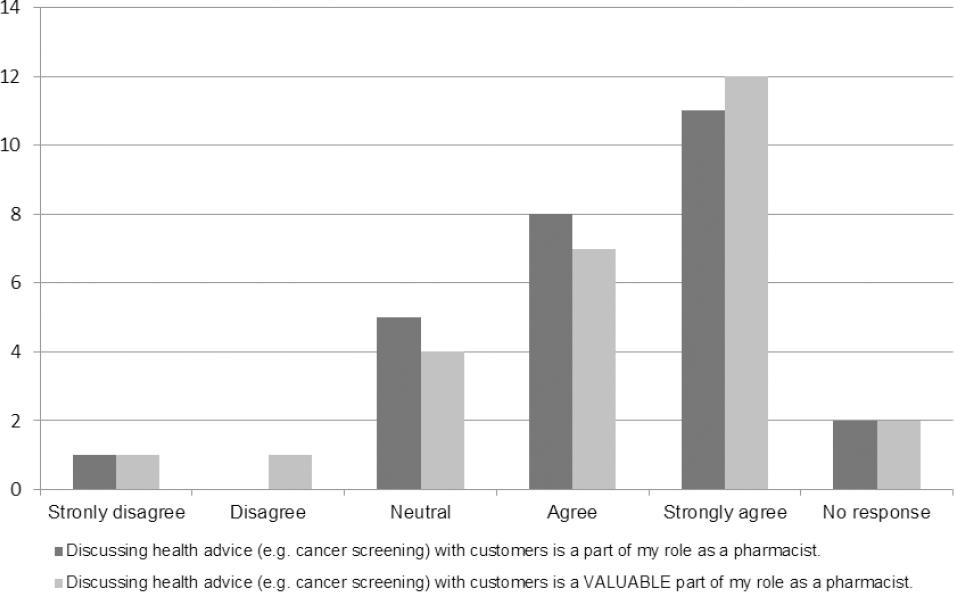

According to the survey, most community pharmacists (71%, n=19) either‘agreed’ or‘strongly agreed’ discussing health advice, such as cancer screening, with their consumers was a part of their role. However, eighteen percent (18%, n=5) of community pharmacists indicated a‘neutral’ response to this question. The same number of community pharmacists (71%, n=19) either‘agreed’ or‘strongly agreed’ discussing health advice with their consumers was a valuable part of their role. Fifteen percent (15%, n=4) of community pharmacists indicated a‘neutral’ response to this question. SeeFigure 1.

Figure 1. Pharmacists’ responses to survey questions about their discussing health advice with their consumers.

In the interviews, community pharmacists reflected on their health promotion role. Community pharmacists described health promotion as integral to their job. One community pharmacist stated:

I think they’re [pharmacists] - that’s what they’re there for... They’re there to promote - or they’re there to do health promotion. That’s what they are there to do. (P:I08)

This community pharmacist went on to explain:

[Y]our community pharmacy is not somewhere you should just be going to get your prescription dispensed. You know, it’s somewhere you should be going as part of your overall health status... [Y]ou should be going to get advice... (P:I08)

Community pharmacists considered the promotion of bowel cancer and breast cancer screening to be consistent with their current health promotion role. They described the promotion of cancer screening as fitting seamlessly with this role. For these reasons, most community pharmacists regard pharmacies as suitable places for the promotion of cancer screening:

I think it [the pharmacy] is an ideal place... [A] primary level type of space to approach people who are already in the pharmacy who are interested in their health, first of all. And who, you know, may be curious and open to those type of suggestions. (P:I07).

Community pharmacists reflected on of the importance of their health promotion role - both generally, and in relation to the promotion of bowel cancer and breast cancer screening specifically. For example, community pharmacists reflected on their potential role in the prevention or early detection of cancer:

You will pick up ... a certain percentage [of people] that have no idea that they may have breast cancer or bowel cancer, so it’s certainly does work... If they have time with a pharmacist or a trained pharmacy staff, they will get positive outcomes from that, and if you get it early enough, you may prevent a long-term hospital stay. (P:I07)

Community pharmacists identified limitations in their current health promotion role. Community pharmacists felt they were not approaching problems at the population-level because their interactions with consumers are individual and often in an acute or post-diagnosis phase. This idea is reflected in the following quote.

[W]e’re dealing with each individual person as they come in, but we’re not globally going out there and going, yes, this is what everyone should do... [T]he thing is, you’re so caught up doing other things that ... you don’t really get a chance to do the sort of a broader scale - And the thing is, you actually want to be talking to the people that don’t have these problems yet, it’s prevention that you’re wanting, whereas I think that’s the problem... - how do we reach those people in a bigger scale? (P:I08)

Another limitation community pharmacists perceive about their current health promotion role is that consumers do not recognise or take advantage of this role. One community pharmacist stated:

[W]e could play a huge role in that [the promotion of cancer screening in pharmacies]... [T]hey [clients] don’t always come and ask, come to us, [be]cause they don’t think ... they can come to us for that. But rather, I think there’s a huge role for that. (P: I04)

In summary, this theme presents community pharmacists perceptions about their health promotion role in community pharmacies. Community pharmacists feel health promotion is an important and relevant aspect of their role because it aligns with the broader holistic health care approach. In particular, community pharmacists consider breast cancer and bowel cancer screening consistent with early detection and prevention philosophies underpinning primary health care. However, they feel their role is limited by individualised consumer care and consumer understanding.

THEME 2: Community pharmacists’ descriptions of their current health promotion roles: “Talking about it was just sort of second nature”.

In the interviews, community pharmacists reflected about their current health promotion role. They describe this role as one which centres around the provision of basic health information and simple screening for common conditions such as skin cancer, hypertension and diabetes. One community pharmacist stated:

So, if you were concerned about that spot, for example, so we would take a picture, that goes ... directly to the specialist, dermatologist, and the patient will get a report within twenty-four to forty-eight hours. And we’ve had many cases where they’ve had to then go to have that looked at by the specialist, next step up. So there’s the - that service that we actually already offer... (P:I04)

Another community pharmacist gave the following example:

[A]t the moment we might do blood pressure testing for cardiovascular risk. We look at, in the diabetes risk assessment ... waist measurement and other sorts of risk factors questionnaires, things like that, that would grade someone’s risk of getting those diseases and then having basically a referral process to the [general practitioner]. (P:I05)

More particularly, community pharmacists reflected about their role in relation to the promotion of bowel cancer screening because it is currently part of their practice

I mean, we do bowel screening [promotion] now, and we were historically always involved in the Rotary bowel screen. So, talking about it was just sort of second nature around that time of year. But we’ve also had the bowel screen kits in store... (P:I01)

A second community pharmacist explained:

[B]owel cancer we do have ... test kits from - so, we do actually sell that. Do we sell a lot of it? No, but we do sell an odd bit, and that’s why I tell the rest of my staff that - look, you need to know how it works, so we’ve actually even got a demonstration kit. (P:I04)

No community pharmacists described a current role in the promotion of breast cancer screening. Some expressed confusion about how they might promote breast cancer screening in future. This was underpinned by community pharmacists’ perceptions about a lack of resources to support their promotion of breast cancer screening in pharmacies. One community pharmacists explained:

So, what am I providing? ... Because, generally when I provide screening, I have a physical role at some point in that process, so whether it’s checking their blood pressure, whether it’s checking their sugar levels, whether it’s just doing a ... risk assessment... I don’t know how you’d do that with breast cancer. (P:I01)

Overall, this theme presents community pharmacists descriptions of their health promotion role in community pharmacies. Community pharmacists describe health promotion as providing basic health information including cancer screening. They understand and accept the process for bowel cancer screening because it is currently part of their practice. However, they are uncertain about breast cancer screening because it is not currently part of their role and foresee resourcing issues.

THEME 3: Community pharmacists’ knowledge and confidence in their health promotion roles: “We’re may be less confident in that area”.

In the survey, most community pharmacists described their confidence as‘average’ or‘good’ when discussing breast cancer (67%, n=18), breast cancer screening (60%, n=16) and breast cancer prevention (56%, n=15). SeeFigure 2. Many community pharmacists described their confidence as‘average’ or‘good’ when discussing bowel cancer (67%, n=18), bowel cancer screening (63%, n=17) and bowel cancer prevention (60%, n=16). SeeFigure 3. Community pharmacists were more likely to describe their confidence as‘excellent’ in relation to the bowel cancer topics and as‘very poor’ in relation to the breast cancer topics.

Figure 2. Pharmacists’ responses to survey questions about their confidence discussing breast cancer topics with their consumers.

Figure 3. Pharmacists’ responses to survey questions about their confidence discussing bowel cancer topics with their consumers.

The quantitative findings were supported by the community pharmacists in the interviews. Most community pharmacists described their confidence to promote bowel cancer and breast cancer screening as moderate. This was because they were uncertain about bowel cancer and breast cancer topics, and about the process of promoting bowel cancer and breast cancer screening. For example, one community pharmacist revealed the following:

I would say my confidence would be moderate at the moment... I would think that I personally would need more education, obviously of the process [of the promotion of cancer screening] and what was going to be offered, and then the referral process as well, and other questions that might come up [from consumers]. (P:I03)

The community pharmacists consistently reflected they felt more knowledgeable and confident in relation to bowel cancer topics than breast cancer topics. This was because, as seen in Theme 2, community pharmacists perceive they have a current health promotion role in relation to bowel cancer screening, but not in relation to breast cancer screening:

Bowel screening [promotion] we do, we’re very good at it. Breast [screening promotion] is... We’re may be less confident in that area. (P:I01)

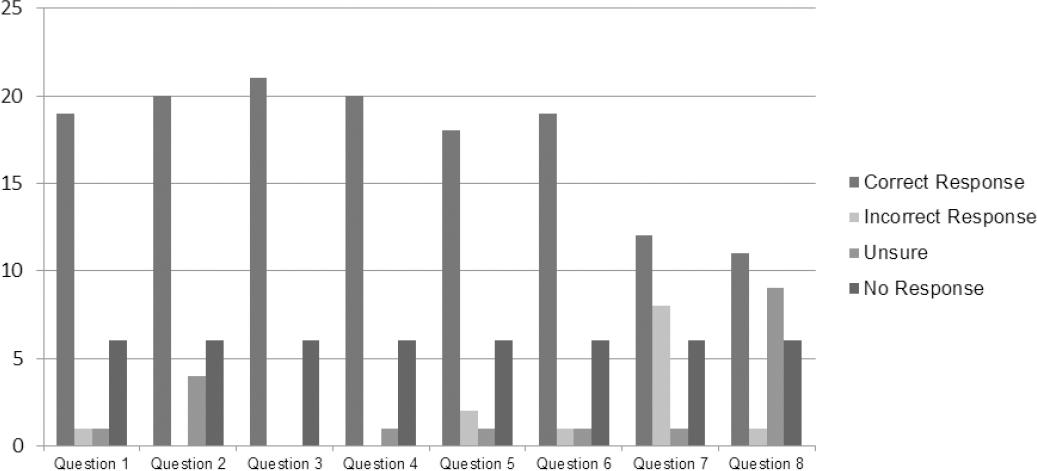

Despite reporting only moderate confidence in discussing breast cancer and bowel cancer with their consumers, the survey demonstrated community pharmacists’ knowledge about bowel cancer and breast cancer topics is acceptable. In the eight knowledge questions about cancer and cancer screening, an average of 82% responded with a correct answer (range: 52% (n=11 [Question 8]) and 100% (n=21 [Question 3])). Again, community pharmacists were more likely to report correct answers in relation to bowel cancer topics than they were in relation to breast cancer topics. SeeFigure 4.

Figure 4. Pharmacists’ responses to survey questions about their knowledge of bowel and breast cancer topics.Question 1: Overweight and obesity increase the risk of both breast and bowel cancer. [TRUE]Question 2: Drinking alcohol above recommended guidelines increases the risk of cancer. [TRUE]Question 3: Smoking tobacco increases the risk of cancer. [TRUE]Question 4: A healthy diet reduces the risk of cancer. [TRUE]Question 5: People over 50 years of age should be screened for bowel cancer every 2 years. [TRUE]Question 6: Only people who have symptoms should be screened for bowel cancer. [FALSE]Question 7: Most breast cancers occur in women over 50 years of age. [TRUE]Question 8: A breastscreen (mammogram) can detect breast cancer before a lump can be felt. [TRUE]

In summary, this theme presents community pharmacists knowledge and confidence in their health promotion roles. Community pharmacists feel more knowledgeable and confident about promoting bowel cancer screening because it is currently part of their practice. They feel less confident about promoting breast cancer screening because they feel unsure about current and relevant knowledge, the screening process, and referral systems. However, according to the electronic survey, most community pharmacists have acceptable knowledge of breast and bowel cancer topics.

DISCUSSION

The community pharmacists who participated in this study perceive their role in health promotion, including in the promotion of bowel cancer and breast cancer screening, to be valuable and integral to their broader role. This is consistent with the literature. Pharmacists perceive this role to be important because they recognise the need for increased cancer screening, feel they can influence consumers to engage in screening and believe consumers appreciate this service.26 27 28-29Pharmacists consider the promotion of cancer screening to add value to their role, and to increase consumers’ confidence in them as health professionals.30

In Australia, community pharmacists are familiar with the concept of health promotion. All the community pharmacists who participated in this research could cite at least one example of a health promotion activity they conduct(ed) in their pharmacy, often in relation to the prevention or early detection of common chronic conditions. These activities were undertaken routinely and as part of broader health promotion events such as‘awareness months’. Under the Quality Care Pharmacy Program31, such health promotion activities are a requirement for pharmacies in Australia.

Many of the community pharmacists described a current role in the promotion of bowel cancer screening - in the sale of bowel screening kits, and educating consumers about the correct use of these kits. The literature agrees pharmacists in Australia have a key role in the promotion of bowel cancer screening because more than three consumers per week present to each community pharmacy in Australia with the mild gastrointestinal symptoms, which may be indicative of malignant disease.18,32Most of the community pharmacists in this study described having bowel screening kits available in-store if requested by a consumer rather than actively promoting the sale of kits. A more active approach to the promotion of bowel screening kits could be an important aspect of pharmacists’ role. The literature suggests pharmacists participate in basic assessment and referral for people presenting with gastrointestinal symptoms.18-20,32

All the community pharmacists in this study perceived themselves as having a role in the promotion of bowel cancer screening but none of the community pharmacists identified a current role in the promotion of breast cancer screening. In international studies, most pharmacists report they do not, or do not frequently or consistently, engage in activities such as responding to inquiries about symptoms, providing advice and educational materials about screening, assessing or enabling self-assessment of risk-factors or referring to screening to promote breast cancer screening.27 28-29When reflecting on a potential future role in promoting breast cancer screening, the community pharmacists in this study were unsure what this would involve except for consumer requests for referral to screening providers.

International literature suggests pharmacists’ current role in the promotion of breast cancer screening centres on education - for example, teaching clinical breast examination and explaining mammography schedules, etc.27,33In this research, community pharmacists’ uncertainty about their role in the promotion of breast screening was underpinned by the lack of educational resources associated with the BreastScreen Australia program. The literature agrees the lack of consumer resources is the most significant barrier to the promotion of breast cancer screening in community pharmacies.27Most pharmacists agree they would be more likely to provide breast cancer health promotion if they have access to consumer education materials about breast cancer.29,34Resources to promote breast cancer screening are an important consideration.

Most of the community pharmacists participating in this study perceived their role in the promotion of bowel and breast cancer screening to be one of information provision. The broader literature suggests pharmacists may have a role in screening for bowel and breast cancer risk using basic assessment tools like those used for identifying risk for chronic health conditions.32,33There is some Australian research about pharmacists’ perceptions of using assessment tools in the promotion of bowel cancer screening18,20but there is limited evidence about breast cancer screening tools for community pharmacists.

The community pharmacists participating in this study identified two limitations they perceive in their current health promotion role: (1) their role focuses on individual consumer rather than a population approach, and (2) the community are unaware of their health promotion role. These are interrelated concepts because a population approach is an added challenge to pharmacists’ health promotion role identified in other research about the promotion of cancer screening in pharmacies.27These limitations highlight the importance of activities to raise awareness of pharmacists’ health promotion roles, if a program for promoting cancer screening in pharmacies is to be effective.

The findings of this research suggest community pharmacists’ knowledge in relation to bowel cancer and breast cancer topics is relatively good despite their perception. This is a novel finding. In the literature searches conducted for this paper, only one previous study from Australia measured pharmacists’ knowledge and this was according to indicators for referral for bowel cancer screening. The findings indicate pharmacists’ knowledge to be variable, with pharmacists correctly identifying consumers to be referred for screening between 30% and 70% of the time.19International literature finds pharmacists’ knowledge in relation to breast cancer and screening to be poor to moderate, however pharmacists are generally enthusiastic to improve their knowledge.27 28-29,34

Despite relatively good knowledge, the community pharmacists in this study report their confidence in discussing cancer and cancer screening to be moderate. The literature agrees discussing cancer in pharmacy settings is perceived by pharmacists as an anxiety-provoking experience because the discussion requires advanced communication skills, and there could be a significant negative impact on consumers if these skills are not applied effectively.35In this study, the community pharmacists were unsure about promoting cancer screening - and, in particular, breast cancer screening - to consumers, which underpinned their lack of confidence. Community pharmacists’ confidence was directly related to their knowledge. Many community pharmacists expressed concern they lacked the knowledge about cancer and screening necessary to respond to the questions asked by consumers. As pharmacists’ confidence in their ability to perform a behaviour, such as health promotion, is crucial in predicting whether they will do so26, these issues must be addressed to increase pharmacists’ self-efficacy and willingness to promote cancer screening.

The finding that pharmacists’ confidence in promoting health is variable is supported by the broader literature. A systematic review concluded pharmacists’ confidence in providing health promotion services generally is “mixed”.26Pharmacists’ confidence in relation to promoting breast cancer screening is inconsistent.27,29,34However, with training, one study found Australian pharmacists were both confident and effective at promoting screening for bowel cancer, including in undertaking relatively complex tasks such as assessing‘alarm symptoms’ and referring to screening.18 19-20,32

Overall, community pharmacists were consistently more confident and knowledgeable in relation to bowel cancer topics than breast cancer topics. The main reason for this finding is because community pharmacists in Australia are already engaged in the bowel cancer screening program, but less engaged with the breast cancer screening program. These are important findings to inform the education of community pharmacists in promoting cancer screening in community pharmacies, which is essential if such a health promotion program is to be effective.

Strengths and limitations

There are some limitations to this research. Firstly, the purposeful sample may have self-selection bias. Secondly, the self-report survey and interviews might have reporting and / or social desirability bias. Thirdly, a small sample from one region limits generalisability but the findings may be useful in understanding similar sample groups.

CONCLUSIONS

This paper presents the findings about promoting bowel cancer and breast cancer screening in community pharmacies in Australia. Specifically, it presents findings related to community pharmacists’ perceptions of their role, knowledge and confidence in relation to cancer screening promotion. Community pharmacists perceive their role in health promotion, including in the promotion of bowel cancer and breast cancer screening, to be valuable and integral to their broader role. Community pharmacists have moderate levels of knowledge and confidence necessary to perform this role. Overall, this research supports the feasibility of promoting bowel cancer screening in community pharmacies. It suggests further training is warranted for community pharmacists to increase their knowledge of breast cancer and their confidence in promoting breast cancer referral and screening services. It highlights the important role community pharmacists have in increasing engagement in the national bowel cancer and breast cancer screening programs, and in potentially decreasing mortality rates of these cancers.