INTRODUCTION

In Australia, medication-related problems result in 250,000 hospital admissions annually at a cost of AUD 1.4 billion.1 Medicines safety issues and medicines use for health in ageing is not only a national concern but a global concern.2,3 The high prevalence of polypharmacy and comorbidities in the Australian community with extensive medication-related problems reported in community dwelling older adults, highlights that more knowledge is needed around medicines safety health initiatives that address medication-related problems.4-6 Medication review is one of the medicines safety initiatives for addressing medication-related problems where pharmacists as medicines experts have a significant role to play.7 While there are many definitions of medication review, a prominent definition is by the Pharmaceutical Care Network of Europe (PCNE): “Medication review is a structured evaluation of a patient's medicines with the aim of optimizing medicines use and improving health outcomes. This entails detecting drug-related problems and recommending interventions”.8

The PCNE classification defines different clinical levels of medication review depending on the types and sources of available information.8 An intermediate review (Type 2b) is based on the patient's medication history and clinical records, without patient involvement or input.9 An example of an advanced medication review (Type 3) and comprehensive approach to medication review provision is the Australian Home Medicines Review (HMR) model, which uses a structured process composed of various administrative and clinical stages, including patient input and involvement during the in-home patient consultation.10 One of the strengths of the HMR model is that the patient assessment occurs in the patient's home surroundings, which enables a full assessment of how the patient manages their medicines. While HMR patient consultations generally occur in the home, the patient has the right to choose the place of the service depending on their preferences, cultural beliefs, and socioeconomic circumstances.11

The Australian HMR service was launched in 2001 to optimize medicines management and enhance Quality Use of Medicines as per Australia's National Medicines Policy.12 The Government-funded service is a collaborative model with the patient at the hub of the health service, and aims to reduce medication-related problems, reduce hospital admissions and optimize medicines use for patient health.10,13 Key to the health service is the accredited pharmacist who aims to identify, prevent and resolve medication-related problems. In Australia, pharmacists can become HMR accredited whereby competency in clinical, therapeutic and communication skills must be demonstrated prior to HMR provision. Once accredited, they can receive referrals from medical practitioners who have identified suitable patients likely to benefit from an HMR.14 Upon receipt of an HMR referral, accredited pharmacists conduct an in-home patient consultation to identify actual and potential medication-related problems, and then collate an HMR report for the patient's General Practitioner (GP). The report makes evidence-based recommendations and suggested interventions to optimize prescribing, improve patient medicines management and identifies important findings and issues such as non-adherence to prescribed therapies.10 The GP together with the patient formulate a medicines management plan to optimize medicines based on the accredited pharmacists' HMR report as per the medication review cycle of care and steps involved for comprehensive medication reviews.11 Prior to 2020, only GPs could refer patients for an HMR. However recent program changes enabled a wider medical practitioner referral base.11 At the time that this study was conducted, only GPs could refer suitable patients for an HMR.14

Since the launch of HMRs in Australia, evidence has grown around the health service benefits. The first systematic review of clinical medication review in Australia (including evidence from HMRs) reported that clinical medication review provision resulted in identification of medication-related problems and improved adherence.15 A reduction in the number of medicines prescribed, potentially inappropriate medicines, hospitalisations and costs were other findings that showed the benefits of clinical medication review in improving the quality use of medicines and health outcomes.15 Studies have shown that HMRs are able detect one to six medication-related problems in patients, system errors in medical records, and can address potentially inappropriate prescribing.1,16,17

Despite HMR program longevity, little has been published around accredited pharmacists' experiences of the clinical health service they provide. Given the growing evidence of clinical benefits, there is little published on the time investment required to perform comprehensive HMRs that form part of the larger medicines management cycle of patient care.11 Therefore, the clinical work performed by these medicines experts warrants further research efforts and was the specific focus of this study.7

The aim of this study was to investigate accredited pharmacists' experiences of time investment across the study's defined three stages of HMR process, for a typical instance of service provision for a single patient.

METHODS

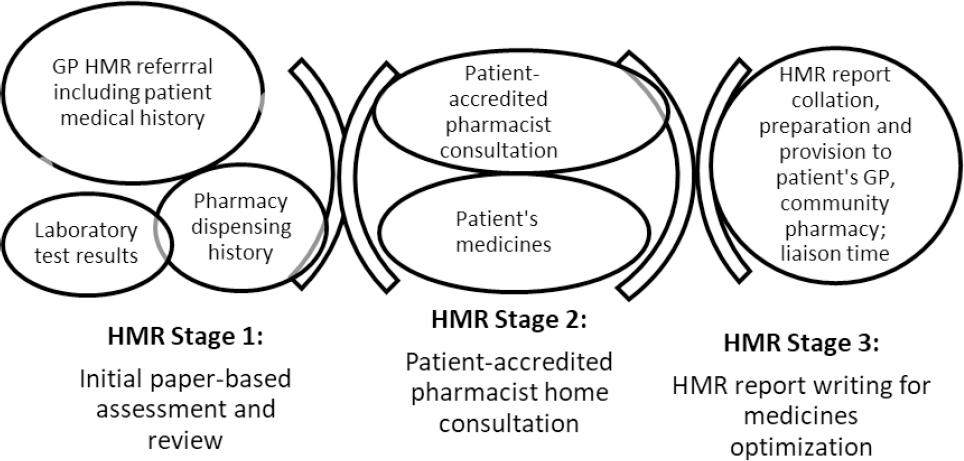

A national online survey anonymously sought accredited pharmacists' experiences of HMR time investment across the three defined stages outlined in this paper. For the purposes of this study, accredited pharmacists' HMR clinical stages have been categorized as follows (Figure 1):

Stage 1: Information-gathering and initial paper-based assessment and review (receipt of GP referral, reason for referral and patient medical and medicines history)

Stage 2: In-home patient-accredited pharmacist consultation (face-to-face with the patient in the home environment with all their medicines; often with carer/family member present)

Stage 3: HMR report writing (accredited pharmacists' collation, generation, and preparation of findings and recommended interventions into a completed HMR report for the referring GP's consideration to optimize prescribing, enhance medicines management and optimize patient health. This stage also included any liaison time required).

Participants were accredited pharmacists who were eligible to participate in the survey if they had performed at least one HMR in the previous year. The Tailored Design method views surveys as social exchange and was used in survey design, construction and deployment.18 A pilot survey was first developed and tested for readability and understanding with practicing accredited pharmacists, academic pharmacists, and consumers. The final survey consisted of demographic questions and questions relating to time investment for HMR Stages 1 to 3 (Online appendix). Convenience sampling was used to distribute the survey nationally by email across Australia from August to September 2016, via the three key professional pharmacist organizations (Australian Association of Consultant Pharmacy, Pharmaceutical Society of Australian and Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia), who sent the survey at least twice. Participants were incentivized to participate in the survey with the chance to win one AUD 100 shopping voucher. Ethics approval (Approval number 1400000561) was sought from QUT Human Research Ethics Committee prior to commencement of the study.

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics v.26, (IBM Corporation, Chicago, IL). Survey time categories were collapsed for the purposes of statistical calculations when checking for relationships between variables. Frequency distributions were used to describe the data and proportions were calculated as percent of available data. A chi-square test of independence was performed to evaluate any association between demographic variables (e.g., age, gender, number of HMRs ever completed during career, pharmacy background and integration into GP clinics) and time investment during HMR Stages. For cells with expected count less than 5, Fisher exact test was conducted. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 255 accredited pharmacists completed the survey, representing approximately 10% of the national accredited pharmacist membership at the time (Table 1). Participants' HMR practice was represented in all states and territories of Australia (Table 1). Demographic variables and time investment for a typical instance of HMR Stages 1 to 3 for a single patient are in Tables 1-4. Most respondents were female (71%), aged >40 years (60%), had completed more than 100 HMRs in their career (73%), and were of community pharmacy background (77%). Hospital pharmacy background accounted for (20%), with the remainder from having a background from other settings such as academia and military pharmacy (3%). Accredited pharmacists fully integrated into GP clinics (co-located in GP clinics with access to clinic resources) were 3% of respondents. A total of 46.7% typically spent: <30 minutes performing Stage 1 (Table 2), and 70.2% spent 30-60 minutes performing Stage 2 (Table 3). For Stage 3, 40.0% typically invested 1-2 hours, and 27.1% invested 2-3 hours in HMR report collation and writing time including any liaison time performed as part of report generation and provision (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic details of respondents and time investment for HMR Stages 1 to 3 (n=255)

| Demographics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| 20-29 | 24 (9.4) |

| 30-39 | 77 (30.2) |

| 40-49 | 56 (22.0) |

| 50-59 | 67 (26.3) |

| 60+ | 31 (12.2) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 74 (29.0) |

| Female | 181 (71.0) |

| Number of HMRs ever completed | |

| 1-49 | 43 (17.0) |

| 50-99 | 26 (10.0) |

| 100-499 | 103 (40.0) |

| 500-999 | 43 (17.0) |

| 1000+ | 40 (16.0) |

| Main Pharmacy Background | |

| Community | 196 (77.0) |

| Hospital | 52 (20.0) |

| Other | 7 (3.0) |

| Integrated into GP clinic | |

| Fully integrated | 7 (3.0) |

| Partially integrated | 41 (16.0) |

| Not integrated | 207 (81.0) |

| State / Territory* | |

| ACT | 3 (1.0) |

| New South Wales | 93 (36.0) |

| Northern Territory | 3 (1.0) |

| Queensland | 45 (17.0) |

| South Australia | 29 (11.0) |

| Tasmania | 10 (4.0) |

| Victoria | 53 (20.0) |

| Western Australia | 26 (10.0) |

| Time investment for HMR Stage 1 | |

| <30 mins | 119 (46.7) |

| 30-45 mins | 72 (28.2) |

| 45-60 mins | 41 (16.1) |

| >60mins | 23 (9.0) |

| Time investment for HMR Stage 2 | |

| <30 mins | 5 (2.0) |

| 30-60 mins | 179 (70.2) |

| 60-90 mins | 65 (25.5) |

| >90 mins | 6 (2.3) |

| Time investment for HMR Stage 3 | |

| <1 hr | 46 (18.0) |

| 1-2 hrs | 102 (40.0) |

| 2-3 hrs | 69 (27.1) |

| 3-6 hrs | 31 (12.2) |

| >6 hrs | 7 (2.7) |

*Note: Respondents could select more than one state or territory of HMR practice (NTotal=262)

Table 2. Chi-square test of independence reporting the relationship of demographic variables and HMR Stage 1 time investment. NTotal=255

| N (%) | <30 mins | 30-45 mins | 45-60 mins | >60 mins | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in Years | 0.200 | ||||

| 20-29 | 11 (45.8) | 4 (16.7) | 3 (12.5) | 6 (25.0) | |

| 30-39 | 41 (53.2) | 19 (24.7) | 12 (15.6) | 5 (6.5) | |

| 40-49 | 29 (51.8) | 14 (25.0) | 9 (16.1) | 4 (7.1) | |

| 50-59 | 29 (43.3) | 22 (32.8) | 11 (16.4) | 5 (7.5) | |

| >60 | 9 (29.0) | 13 (41.9) | 6 (19.4) | 3 (9.7) | |

| Gender | 0.440 | ||||

| Female | 85 (47.0) | 53 (29.3) | 30 (16.6) | 13 (7.2) | |

| Male | 34 (45.9) | 19 (25.7) | 11 (14.9) | 10 (13.5) | |

| Number of HMRs completed during career | 0.010* | ||||

| 1-49 | 13 (30.2) | 10 (23.3) | 11 (25.6) | 9 (20.9) | |

| 50-99 | 13 (50.0) | 9 (34.6) | 2 (7.7) | 2 (7.7) | |

| 100-499 | 48 (46.6) | 25 (24.3) | 20 (19.4) | 10 (9.7) | |

| 500-999 | 21 (48.8) | 18 (41.9) | 3 (7.0) | 1 (2.3) | |

| >1000 | 24 (60.0) | 10 (25.0) | 5 (12.5) | 1 (2.5) | |

| Pharmacy background n= 248 | 0.980 | ||||

| Community | 92 (46.9) | 54 (27.6) | 33 (16.8) | 17 (8.7) | |

| Hospital | 24 (46.2) | 15 (28.8) | 8 (15.4) | 5 (9.6) | |

| Integration into GP clinic | 0.643 | ||||

| Fully integrated | 3 (42.9) | 4 (57.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Partially integrated | 21 (51.2) | 10 (24.4) | 5 (12.2) | 5 (12.2) | |

| Not integrated | 95 (45.9) | 58 (28.0) | 36 (17.4) | 18 (8.7) |

* = statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05)

Note: Only 7/255 were of other pharmacy backgrounds. These numbers were too small for statistical analysis. NTotal was adjusted as 248 for analysis of these variables.

For cells with expected count less than 5, Fisher exact test was conducted.

Table 3. Chi-square test of independence reporting the relationship of demographic variables and HMR Stage 2 time investment. NTotal=255

| N (%) | <30 mins | 30-60 mins | 60-90 mins | >90 mins | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in Years | 0.090 | ||||

| 20-29 | 1 (4.2) | 19 (79.2) | 3 (12.5) | 1 (4.2) | |

| 30-39 | 0 (0.0 | 61 (79.2 | 14 (18.2 | 2 (2.6 | |

| 40-49 | 3 (5.4) | 34 (60.7) | 19 (33.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 50-59 | 1 (1.5) | 47 (70.1) | 18 (26.9) | 1 (1.5) | |

| >60 | 0 (0.0) | 18 (58.1) | 11 (35.5) | 2 (6.5) | |

| Gender | 0.030* | ||||

| Female | 4 (2.2) | 118 (65.2) | 55 (30.4) | 4 (2.2) | |

| Male | 1 (1.4) | 61 (82.4) | 10 (13.5) | 2 (2.7) | |

| Number of HMRs completed during career | 0.510 | ||||

| 1-49 | 0 (0.0) | 30 (69.8) | 11 (25.6) | 2 (4.7) | |

| 50-99 | 2 (7.7) | 19 (73.1) | 5 (19.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 100-499 | 2 (1.9) | 70 (68.0) | 29 (28.2) | 2 (1.9) | |

| 500-999 | 1 (2.3) | 29 (67.4) | 13 (30.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| >1000 | 0 (0.0) | 31 (77.5) | 7 (17.5) | 2 (5.0) | |

| Pharmacy background n=248 | 0.072 | ||||

| Community | 3 (1.5 | 143 (73.0 | 45 (23.0 | 5 (2.6 | |

| Hospital | 2 (3.8) | 31 (59.6) | 19 (36.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Integration into GP Clinic | 0.730 | ||||

| Fully integrated | 0 (0.0) | 6 (85.7) | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Partially integrated | 1 (2.4) | 29 (70.7) | 9 (22.0) | 2 (4.9) | |

| Not integrated | 4 (1.9) | 144 (69.6) | 55 (26.6) | 4 (1.9) |

* = statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05)

Note: Only 7/255 were of other pharmacy backgrounds. These numbers were too small for statistical analysis. NTotal was adjusted as 248 for analysis of these variables.

For cells with expected count less than 5, Fisher exact test was conducted.

There was a significant difference among those with greater HMR career experience (greater number of HMRs ever performed) for time spent in Stage 1 (p=0.01) and a trend to significance for Stage 3 (p=0.10) (Table 2 and Table 4 respectively). Greater HMR career experience required a shorter time to perform Stages 1 and 3 compared to less experienced HMR pharmacists. There was also a significant factor in terms of gender and time investment in Stage 2, where females performed statistically significant longer in-home patient consultations than male counterparts (p=0.03) (Table 3). Other demographic variables did not appear to statistically significantly influence HMR time investment.

Table 4. Chi-square test of independence reporting the relationship of demographic variables and HMR Stage 3 time investment. NTotal=255

| N (%) | <1hr | 1-2 hrs | 2-3 hrs | 3-6 hrs | >6 hrs | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in Years | 0.820 | |||||

| 20-29 | 4 (16.7) | 12 (50.0) | 5 (20.8) | 3 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 30-39 | 15 (19.5) | 29 (37.7) | 20 (26.0) | 11 (14.3) | 2 (2.6) | |

| 40-49 | 6 (10.7 | 28 (50.0) | 17 (30.4) | 3 (5.4) | 2 (3.6) | |

| 50-59 | 16 (23.9) | 21 (31.3) | 18 (26.9) | 10 (14.9) | 2 (3.0) | |

| >60 | 5 (16.1) | 12 (38.7) | 9 (29.0) | 4 (12.9) | 1 (3.2) | |

| Gender | 0.210 | |||||

| Female | 27 (14.9) | 71 (39.2) | 52 (28.7) | 25 (13.8) | 6 (3.3) | |

| Male | 19 (25.7) | 31 (41.9) | 17 (23.0) | 6 (8.1) | 1 (1.4) | |

| Number of HMRs completed during career | ||||||

| 1-49 | 7 (16.3) | 14 (32.6) | 11 (25.6) | 9 (20.9) | 2 (4.7) | 0.100** |

| 50-99 | 3 (11.5) | 7 (26.9) | 11 (42.3) | 4 (15.4) | 1 (3.8) | |

| 100-499 | 19 (18.4) | 43 (41.7) | 25 (24.3) | 12 (11.7) | 4 (3.9) | |

| 500-999 | 7 (16.3) | 15 (34.9) | 17 (39.5) | 4 (9.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| >1000 | 10 (25.0) | 23 (57.5) | 5 (12.5) | 2 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Pharmacy background n=248 | 0.590 | |||||

| Community | 33 (16.8) | 81 (41.3) | 54 (27.6) | 24 (12.2) | 4 (2.0) | |

| Hospital | 11 (21.2) | 20 (38.5) | 12 (23.1) | 6 (11.5) | 3 (5.8) | |

| Integration into GP clinic | 0.800 | |||||

| Fully integrated | 2 (28.6) | 3 (42.9) | 2 (28.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Partially integrated | 7 (17.1 | 17 (41.5) | 8 (19.5) | 8 (19.5) | 1 (2.4) | |

| Not integrated | 37 (17.9) | 82 (39.6) | 59 (28.5) | 23 (11.1) | 6 (2.9) |

**= marginally significant towards the predicted direction (0.05 > p ≤0.10)

Note: Only 7/255 were of other pharmacy backgrounds. These numbers were too small for statistical analysis. NTotal was adjusted as 248 for analysis of these variables.

For cell counts less than value of 5 – Fisher exact test was used.

A total of 92.2% of participants reported that the longest patient consultation ever performed (Stage 2) for a single patient during their career was >60 minutes, of which 55.3% reported a duration of >90 minutes, and 18.8% reported a duration of >2 hours. Most participants reported the longest time ever performed for Stage 3 (HMR report collation, preparation, completion, provision, and liaison time) was a duration of >2 hours (87.8%), of which 60.4% reported >3 hours, 23.1% reported >6 hours, and 11.0% reported a duration of >8 hours.

DISCUSSION

This study extended previous knowledge and looked at time investment as a primary outcome with accredited pharmacists as the key stakeholders, most of whom were experienced HMR providers, having performed >100 HMRs. This national study sought accredited pharmacists' perspectives of time investment for each of the 3 Stages of HMR for a typical instance of HMR service provision.

Previous studies have reported an average of 3 to 3.5 hours to complete HMR i.e. 3 HMR Stages.19-22 This is in contrast to the current study which found that time investment can be significantly longer. Differences could be due to differing primary focus of the studies, and only asking about average HMR times.19,20,22 The study which asked about specific HMR time investment in separate stages was only disseminated to one of the eight jurisdictions in Australia.21 This present study is the only one in Australia, which was disseminated to all jurisdictions in Australia, and asked about time investment per HMR stage. This is important because separating out the question and asking about HMR delivery in separate stages provides more granular data. Different time spent in HMR may also be due to changes in the HMR Program delivery and funding model over several years. It is also important to note that this survey was disseminated in 2016, 2 years after HMR capping was introduced (capping accredited pharmacists' service provision to only 20 HMRs per month due to limited Program funding); this may have impacted on time reported by accredited pharmacists.

As reported by respondents in this survey, extended patient consultation time can occur, and this could be for a myriad of reasons. These could include accredited pharmacist-related factors, such as provision of patient education or social or mental health support to enhance patients' overall sense of wellbeing, or performing tasks such as removing unwanted and unused medicines from the home for safe and appropriate disposal.23,24

The duration of the home consultation could also be due to patient-related factors, such as the complexity of the patient's overall medicines regimen, discovering multiple medication-related problems, and uncovering previously unreported patient health issues or concerns to report back to the referring GP. However, lengthy consultations could also indicate inefficiency and inexperience with in-home patient consultations such as being unable to prioritize and unable to keep patient conversations in check.25 Understanding time investment is important as this can impact on patient satisfaction, and focusing on being too efficient (merely getting the job done) over being thorough risks little or no patient involvement in the consultation process.23,26,27 Important tasks that could impact on HMR consultation time include spending sufficient time to focus on the person and their carer/ family member seeking concerns about their care that takes into account multimorbidity and treatment burden, assessing older people's functional ability to manage their medicines using structured tools and assessing home surroundings to address both the person and their environment to enhance health.27-31 Other tasks that could impact on time investment include motivational interviewing, understanding patient medicines goals as part of shared health decision-making, exploring patients' concerns and lived experiences with medicines and their level of health and medicines literacy to better plan individualized care plans to understand problems and challenges faced by polypharmacy comorbid patients.32-34

Another interesting finding from the present study about HMR patient consultations was the longer time that female accredited pharmacists spent. This has not been explored by any of the other previous Australian HMR literature, but is consistent with GP literature, where female GPs spent longer time during patient consultations than male GPs and offered more lifestyle advice, dealt with more problems and exchanged more information.23 The higher proportion of female respondents in the present study may have influenced findings, but it is important to note as the Australian pharmacy workforce is female dominant. It is not unexpected that previous work notes that accredited pharmacists require less time to perform HMRs, the more HMRs they perform.19 More specifically, this study highlighted that it is in fact in Stage 1 (predominantly) and Stage 3 where time efficiencies occur. Unfortunately, the survey could not explore reasons behind the time shift, but it could be due to performing tasks in other stages where it is more practical and fits better with workflow, or due to other factors.

Further knowledge around patient views from both short and longer patient-accredited pharmacist consultations, and what constitutes a “good HMR consultation” is needed to expand upon the present study, especially as medication review consultations tend to be the most time consuming interactions between patients and pharmacists.11,35 The present study also identified 14.9% of accredited pharmacists typically invested >3 hours, of which 2.7% typically invested >6 hours in HMR report collation and writing for a single patient. Further research could explore the specific written communication style, content and methods of HMR report writing to better understand the reasons for extensive time spent in Stage 3.The findings in this study are an interesting outcome in the context of patient-centred care and shared decision-making for comorbid polypharmacy patients to comprehensively report back to the patient's GP any findings, recommendations, and suggested interventions for medicines optimization; and are relevant for workforce planning purposes. Further research could explore the way that HMR time is spent, including exploring further any gender differences, and uncovering how HMR reports are written.

Future directions

In 2020, HMR program changes were introduced to address long-awaited gaps in the existing model. These included the availability of hospital-initiated reviews and additional accredited pharmacist follow-up service to the initial HMR performed, enabling a wider health professional referral base and wider collaboration framework.11 Future work could include a new survey of HMR time investment across 3 Stages of practice. As time investment differences have now been established, better understanding of accredited pharmacists' HMR work processes and opportunities for efficiencies can be further explored. HMR efficiencies could address gaps and impediments to health service access that still exist in the marginalized such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and address the disconnect between the current level of HMR service provision and the needs of the Australian population, especially in remote and rural locations.5,36-38

Given the time investment identified in this study, ongoing research and evaluation should drive further improvements and HMR program changes to help uncover the complexities of HMR work processes and better understand the health service value.11 This is essential given the high prevalence of polypharmacy in the Australian community and the extent of medication-related problems reported in community dwelling older adults.4,5 A mentoring program could assist with time efficiencies especially for newly accredited pharmacists.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study was the importance of establishing time spent performing health activities performed by accredited pharmacists especially when there is no systematic and accurate documentation of complex phenomena.39 The findings have given national voice to their experiences of HMR time investment across 3 HMR Stages which were lacking in the recent literature. Most respondents were experienced (had conducted >100 HMRs), providing credible voice to HMR service and could be an essential starting point for planning HMR program evaluation, quality improvement and workforce planning to address Australian population health needs.5 Limitations include the small sample size and data could be subject to a degree of recall error. However there is no reason to assume the data is unreliable, although recognizing that specific claims about times and inefficiencies cannot be verified. Other limitations included that travel time was not in scope, and the absence of patient medical history data (and therefore level of patient complexity) created the inability to correlate any differences in time expenditure. However further research could expand upon these findings and directly observe patient-accredited pharmacist home consultations and analyze the content and complexity (or simplicity) of accredited pharmacists' written clinical HMR reports to better understand reasons for time investment.

CONCLUSIONS

This study established that the time to conduct HMRs can be varied and extensive. The significant overall time invested in performing comprehensive HMRs for medicines optimization provides an argument to better understand and acknowledge the efforts undertaken by accredited pharmacists for optimizing medicines use and improving health. Insight into accredited pharmacists' experiences of HMR time investment was highlighted. This provides better understanding of HMR process, providing insight for program, policy, and workforce considerations, and a platform for further HMR practice research.