Hope is a multidimensional psychological construct related to the expectation a person has of achieving desirable outcomes based on realistic future objectives (Nayeri et al., 2020). There are more than 30 instruments to measure hope (Schrank et al., 2008), including Snyder's Hope Scale (Snyder et al., 2005), Miller Hope Scale (Miller & Powers, 1998), and the Herth Hope Scale (Herth, 1992), the last one being one of the most widely-used in clinical and research contexts (Nayeri et al., 2020). The HHI is a hope measure based on Dufault and Martocchio's model (Dufault & Martocchio, 1985) that includes three factors: temporality and future, positive expectation, and interconnection. It was initially developed with a 30-item scale with a reliability of .75-.84 and administered to 480 people (Herth, 1992). A short, 12-item version was subsequently created with a Cronbach's α of .97 in 172 patients with acute, chronic, or terminal illness (Herth, 1991) and in which the three original factors accounted for 41% of the scale's total variance (Nayeri et al., 2020; Rustøen et al., 2018).

The scale has been translated into numerous languages and administered in various populations, including patients with mental illness, cancer, palliative care, young people with attempted suicide, university students, the elderly, amongst others (Chan et al., 2011; Gronier et al., 2023; Ripamonti et al., 2012; Yaghoobzadeh et al., 2018). Since then, a series of studies have been conducted with patients (Ali et al., 2022; Cohen et al., 2022), caregivers (Altınışık et al., 2022; Hunsaker et al., 2016), and in the general population (Chan et al., 2011). Studies of the HHI's psychometric properties has yielded disparate results. Some have confirmed the original three-factor structure (Ishimwe et al., 2020; Nikoloudi et al., 2021; Rajandram et al., 2011), most studies report a two-factor structure that explains between 38% and 56% of the variance (Gronier et al., 2023; Haugan et al., 2013; Hunsaker et al., 2016; Sánchez-Teruel et al., 2020, 2021; Yaghoobzadeh et al., 2018), yet still others have found unifactorial structures (Geiser et al., 2015; Ripamonti et al., 2012; Robles-Bello & Sánchez-Teruel, 2022). These divergent results may be influenced by the use of different analytic approaches, small samples, and diverse cultural contexts and suggest that there is no one empirically confirmed construct of the phenomenon of hope quantified by the HHI.

The HHI has shown evidence for its use in a variety of populations (Ishimwe et al., 2020; Yaghoobzadeh et al., 2018), but few studies have analyzed its invariance according to age and sex. Invariance guarantees that measurement tools truly gauge the same construct with the same properties, regardless of the characteristics of the people or groups being evaluated (Putnick & Bornstein, 2016). The HHI has proven to be invariant with respect to sex and age in the general Spanish population (Robles-Bello & Sánchez-Teruel, 2022), with 9 items and one factor.

Assessing hope in cancer patients is crucial for several reasons. Firstly, hope serves as a vital component of patients' psychological and emotional well-being and can influence their quality of life (Tao et al., 2022). Patients with hope may be more motivated to engage in treatment and adhere to medical recommendations, potentially enhancing their treatment response and survival (Altınışık et al., 2022; Cohen et al., 2022). For some patients, hope holds a significant spiritual aspect, providing a source of strength and support during challenging times (Tao et al., 2022). Patients with high levels of hope may perceive a sense of purpose and meaning in their life, which can bolster their ability to cope with cancer more effectively (Jimenez-Fonseca et al., 2018). Additionally, hope can be linked to resilience, which refers to the capacity to recover from and adapt to adverse situations (Li et al., 2016). Patients with greater hope may exhibit enhanced emotional resilient and improved coping abilities when confronting cancer and its side effects (Calderon et al., 2022).

Moreover, evaluating hope can assist healthcare professionals in identifying patients at risk of experiencing depression or anxiety, which can negatively affect their ability to manage cancer and its treatment. Assessing hope can also enable healthcare professionals to tailor information and communication about cancer diagnosis and treatment to patients' needs and expectations, potentially improving their satisfaction and experience within the healthcare system (Ali et al., 2022; Tao et al., 2022).

So far as we know, there have been no psychometric studies of the HHI performed in individuals with metastatic cancer in Spain to date. We deem this to be highly relevant, given the importance of hope in coping and decision making in cancer patients (Obispo-Portero et al., 2022; Tao et al., 2022). The present instrumental study pursues the following aims: (i) to evaluate the dimensionality and factorial structure of the HHI in Spanish patients with cancer, (ii) assess the measurement invariance of the HHI scores in groups defined by sex, age, tumor site, and survival, (iii) probe the appropriateness and accuracy of the measure in this type of population, and (iv) assess the external validity of the HHI scores with resilience and spiritual well-being.

Method

Participants

A total of 863 patients participated in this study. In this sample, 473 (55%) were male and 390 (45%) female. Mean age was 65.4 years old (SD = 10.7). Most were married or partnered (67%), had a primary level of education (48%), and half of the participants' employment status was retired or unemployed. As for clinical characteristics, the most common tumors were thorax (32%), digest (40%), and others (28%). Adenocarcinoma histology was the most frequent (63%) and most cancers were stage IV (80%). The most widely used treatment was chemotherapy (53%), immunotherapy (7%), and targeted drugs (5%). Estimated survival was less than 18 months in 45% of the sample (see Table 1).

Table 1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics (N = 863)

| Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 473 | 54.8 |

| Female | 390 | 45.2 |

| Age | ||

| ≤60 years | 266 | 30.8 |

| 60-70 | 317 | 36.7 |

| >70 | 280 | 32.4 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married/ partnered | 582 | 67.4 |

| Not partnered | 281 | 32.6 |

| Educational level | ||

| Primary | 410 | 47.5 |

| High school or higher | 453 | 52.5 |

| Employed | ||

| No | 456 | 52.8 |

| Yes | 407 | 47.2 |

| Cancer site | ||

| Thoracic | 277 | 32.1 |

| Digestive | 341 | 39.5 |

| Others | 245 | 28.4 |

| Histology | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 544 | 63.0 |

| Others | 319 | 37.0 |

| Cancer stage | ||

| Locally Advanced | 174 | 20.2 |

| Metastatic Disease (IV) | 689 | 79.8 |

| Estimated survival | ||

| <18 months | 393 | 45.5 |

| >18 months | 470 | 54.5 |

| Type of treatment | ||

| Chemotherapy | 455 | 52.7 |

| Immunotherapy | 62 | 7.2 |

| Targeted | 46 | 5.3 |

| Others | 300 | 34.8 |

Instruments

Socio-demographic characteristics were collected using a standardized self-report form. Clinical variables related to cancer and antineoplastic treatment were obtained by the medical oncologist from the patients´medical records.

The Herth Hope Index (HHI) (Herth, 1992) measures various dimensions of hope using a 4-point Likert scale that ranges from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree) with items #3 and #6 reverse-coded, we used the Spanish version of HHI (Sánchez-Teruel et al., 2020). The original english version has three factors: (a) temporality and future that appraises thoughts (sum of items 1, 2, 6, and 11); (b) positive readiness and expectancy dimension (sum of items 4, 7, 10, and 12), and (c) interconnectedness (sum of items 3, 5, 8, and 9). The scale has a global score of 12 to 48, as well as single-item scores from 1 to 4 (Herth, 1992). Higher scores denote greater hope. The estimated internal consistency coefficient for the original scale was .97 (Herth, 1992); in a Spanish sample, the cronbach's α was .97 (Sánchez-Teruel et al., 2020).

The Brief Resilient Coping Scale (BRCS) is a unidimensional outcome measure consisting of 4-item (Sinclair & Wallston, 2004) designed to assess an individual's ability to adapt to stress and adversity, commonly referred to as resilience. Items are scored from 1-5; 1 equal “strongly disagree” and 5 means “strongly agree”. The sum score ranges from 4 to 20; the higher the score, the more resilient the coping strategy. The internal consistency of the BCRS scores in a sample of Spanish cancer patients was (ω = .86) (Calderon et al., 2022).

Spiritual well-being scale was appraised by the validated Spanish version of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-Sp) (Jimenez-Fonseca et al., 2018; Peterman et al., 2002). This instrument consists of 12 items scored on a five-point scale and contains two subscales, meaning/ peace and faith. The sum yields the index of spiritual well-being. The higher the score, the greater the person's wellbeing. Reliability for the scale scores was between .85 - .86 in the Spanish sample (Jimenez-Fonseca et al., 2018).

Procedure

A prospective, multi-institutional, observational study was conducted across 15 tertiary referral hospitals in Spain from February 2020 to November 2022 (for more detail, see (Velasco-Durantez et al., 2023). Funded by the Bioethics group of the Spanish Society of Medical Oncology (SEOM), the study was approved by ethics committees and by the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices (AEMPS; ID: ES14042015). Participants were ≥18 years with resected, histologically-confirmed, advanced cancer not eligible for surgery/ therapy. Data collection was similar across hospitals and data relating to the participants were obtained from the institutions where they received treatment. Participation was voluntary, anonymous, and in no way impacted patient care. Those who agreed to participate signed the consent form and received instructions on how to complete the written questionnaires. Participants filled out the questionnaires at home and returned them to the auxiliary staff during the next visit. Data collection procedures were consistent across all hospitals, with participants data obtained from their respective treating institutions. Data were collected and updated by the attending medical oncologist through a web-based platform (https://www.neoetic.es).

Data Analysis

Analyses were performed sequentially in keeping with the afore-mentioned purposes. First, exploratory factor-analytic solutions intended to ascertain the dimensionality and structure of the HHI scores were fitted using the FACTOR software (Ferrando & Lorenzo-Seva, 2017) following a double cross-validation schema. Second, because a clear, stable structure was detected, a restricted confirmatory factor-analytic solution (CFA) was fitted in the entire sample with the Mplus software (Muthén & Muthén, 2012). To conduct both exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses, we divided the sample into two halves using Solomon method (Lorenzo-Seva, 2022). This method aims to split the sample into two halves, generating two subsamples with equivalent levels of common variance. All the structural solutions at the item level were fitted using robust unweighted least squares estimation. In the EFA solutions, an empirical robust test statistic called LOSEFER, which corrects moments up to the fourth order was used (Lorenzo-Seva & Ferrando, 2023). In assessing model fit and appropriateness, we considered indices from three groups that examined different facets of fit: absolute fit (GFI and RMSR), relative fit concerning degrees of freedom (RMSEA), and comparative fit (CFI). These indices were chosen from all available options to provide a comprehensive evaluation. As for reference values, GFI and CFI values ≥ .95 are indicative of good model fit (Schermelleh-Engel et al., 2003), whereas SRMR values ≤ .08 and RMSEA values ≤ .06 are deemed indicative of satisfactory fit. In the EFA solutions, the adequacy of matrix correlation to be factor analyzed, Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test for sampling adequacy was computed. Normed-MSA indices were also examined to determine if any item failed to share enough communality with the entire set of items: values below .50 suggest that the item does not measure the same domain as the remaining items in the pool and, hence, should be removed (Lorenzo-Seva & Ferrando, 2021). Optimal Implementation of Parallel Analysis was computed to assess the advised number of factors to be extracted (Timmerman & Lorenzo-Seva, 2011). The following indices were used to judge essential unidimensionality: Explained Common Variance (ECV) and Mean of Item Residual Absolute Loadings (MIREAL). ECV values > .85 and MIREAL < .30 suggest that the data can be treated as fundamentally unidimensional (Ferrando & Lorenzo-Seva, 2018). To study the replicability of the factor structure obtained in the first Solomon subsample, a CFA was carried out on the second Solomon subsample using the procedure and criteria described thus far. To determine whether there were pairs of items with correlated errors, we computed Robust Absolute Residuals (RAR), Robust Anti-Image-Based Partial Correlation (RAIPC), EREC, and ENIDE (Ferrando et al., 2022). Finally, as both previous analyses led to the same conclusions, the common CFA solution was fitted to the total sample to use all the information available from the data. The CFA parameterization was used to gauge measurement invariance, whereas the corresponding IRT parameterization was applied to exam appraise the functioning of the items and the properties of the test scores. Measurement invariance was evaluated by fitting the prescribed CFA solution in groups defined by gender (two groups), age (three group levels), tumor site (three groups), and expected survival (two groups). All the analyses sought to test for the strong or scalar invariance. If this condition is attained, it can be assumed that the HHI items function with the same measurement properties in all the groups considered and, that mean group differences in the HHI scores can therefore be validly interpreted as reflecting ‘true' group differences. Item functioning was assessed using: (a) the item discriminating power and (b) the boundary category thresholds. As for the scores, we considered IRT-based scores and gauged their conditional and marginal reliability. The behavior of the simple raw scores as a ‘proxy' for the IRT scores was also appraised. Finally, evidence of convergent validity was obtained by fitting a structural equation model in which the ‘internal' CFA solution was extended to include the BCRS and FACIT scores to the data as external variables.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Structure Assessment of HHI

Descriptive statistics of the HHI can be found in Table 2. Item scores ranged from 1.40 (item 3) to 3.68 (item 12). HHI item score distributions were unimodal and asymmetrical (negatively skewed), thereby indicating that most of the values were concentrated at the highest end of the response scale. Therefore, all the structural models used categorical-variable methodology, treating the item scores as ordered-categorical. Nevertheless, some distortions can be expected at the scoring level (see below).

Table 2. Characteristics Gauged by the Hert Hope Index (HHI) Items

| Items | M | SD | Skews |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive outlook on life | 3.55 | 0.72 | -1.60 |

| Presence of goals | 3.07 | 1.00 | -0.67 |

| Feeling all alone a | 1.40 | 0.86 | 2.06 |

| Capable of seeing possibilities despite difficulties | 3.14 | 1.10 | -0.55 |

| Faith that comforts | 2.91 | 1.10 | -0.55 |

| Scared about the future a | 2.56 | 1.11 | -0.55 |

| Recalling happy/ joyful times | 3.66 | 0.65 | -2.06 |

| Deep inner strength | 3.31 | 0.81 | -0.91 |

| Giving and receiving care/ love | 3.63 | 0.63 | -1.68 |

| A sense of direction | 3.35 | 0.82 | -0.99 |

| Belief that each day has potential | 3.65 | 0.64 | -1.95 |

| Belief that life has value and worth | 3.68 | 0.63 | -2.12 |

Note: aItems 3 and 6 are reverse-coded.

Exploratory Factor Analyses

The inter-item polychoric correlation matrix had good properties KMO = .906. Normed-MSA for items ranged from .635 to .962. These outcomes indicated that the correlation matrix is well suited for factorial analysis. For items 3 and 6, however, the estimates did not significantly differ from the threshold value of .5.

Parallel analyses revealed that a single dimension accounted for 61.6% of the common variance and suggested a single factor to be extracted. However, the essential unidimensionality index values were ECV = .838, and MIREAL = .257. The values of the indices are close but slightly below the threshold values for essential dimensionality.

We also inspected the corresponding indices at the item level: items 3 and 6 showed values close to zero. The unidimensional factor analysis solution yielded acceptable goodness-of-fit levels: RMSEA = .051, CFI = .991, GFI = .986, and RMSR = .069. The communality of items to this single factor were < .20, except for items 3 and 6. These outcomes also point toward a single dimension underlying the dataset, except for the contributions of items 3 and 6.

To inspect pairs of items that might have correlated errors, we computed four indices (RAR, RAIPC, EREC, and ENIDE), all coincided in pointing toward two pairs of items as plausibly having correlated errors. The suspicious pairs were 1 and 2 and 11 and 12. Failure to factor in these redundancies could distort the results; consequently, we addressed them (see below). As the EFA solution cross-validated well in both samples, our final conclusions were that: (1) a single factor model was acceptable; (2) items 3 and 6 did not contribute to this factor and could be eliminated from the set of items, and (3) two pairs of items with correlated errors were present in the data, see Table 3.

Table 3. Calibration Results of Hert Hope Index (HHI) in the Total Sample

| Item | Factor loading | Slope | b1 | b2 | b3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.752 | 1.141 | -2.677 | -1.724 | -0.567 |

| 2 | 0.578 | 0.708 | -2.316 | -0.942 | 0.184 |

| 4 | 0.717 | 1.027 | -2.512 | -1.161 | 0.418 |

| 5 | 0.539 | 0.639 | -1.812 | -0.815 | 0.460 |

| 7 | 0.727 | 1.059 | -2.903 | -2.059 | -0.901 |

| 8 | 0.855 | 1.651 | -2.282 | -1.082 | -0.039 |

| 9 | 0.843 | 1.565 | -2.794 | -1.777 | -0.626 |

| 10 | 0.765 | 1.186 | -2.552 | -1.217 | -0.162 |

Confirmatory and Multiple Group Analyses

The total group CFA solution and the multiple-group solutions specified above had excellent fit, which provides ample support about the tenability of the strong invariance hypothesis. On the basis of this invariance, mean group differences in the HHI construct can be meaningfully interpreted. However, results in Table 4 reveal that no significant mean group differences appear in any case. In our view, these results reflect a “ceiling” effect anticipated above: the reported levels of Hope are so consistently high in general, that there is no room for strong group differences to emerge.

IRT Item and Score Properties and Measurement Accuracy

Columns 2-5 in Table 4 show the item parameter estimates in IRT metric. Commensurate with the factorial loadings, discriminations rate high for a personality test which again, evidences the strong internal consistency of the scale, but also, possibly, certain content redundancy. The category parameters tend to be all negative, thereby indicating item “easiness” in the sense that, only a moderate level of hope is required to endorse the highest response category.

Table 4. Test for Invariance Across Sex, Age Group, Tumor Site, and Survival

| Groups | Mean | χ2 (df) | CFI | RMSEA | 90% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Men (fixed) | 0.00 (fixed) | 142.01(94) | 0.99 | 0.034 | 0.022; 0.046 |

| Women | -0.005 | ||||

| Age group (years) | |||||

| Group 1 (≤ 60) (fixed) | 0.00 (fixed) | 192.17 (155) | 0.99 | 0.029 | 0.01; 0.041 |

| Group 2 (60-70) | 0.01 | ||||

| Group 3 (≥ 70) | -0.03 | ||||

| Tumor site | 165.18 (155) | 0.99 | 0.015 | 0.00; 0.032 | |

| Group 1 (thorax) | 0.00 (fixed) | ||||

| Group 2 (digest) | 0.09 | ||||

| Group 3 (others) | 0.05 | ||||

| Survival | |||||

| Group 1 (< 18 month) | 0.00 (fixed) | 118.28 (94) | 0.99 | 0.024 | 0.00; 0.037 |

| Group 2 (≥ 18 month) | 0.04 |

Note. None of the mean differences is statistically significant.

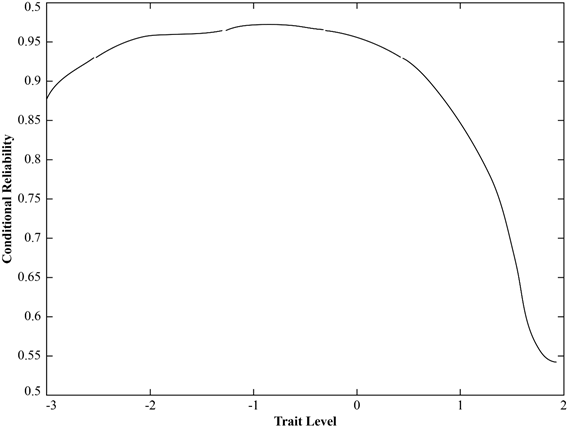

As for the score properties, two types of scores were computed based on the solution in Table 4: EAP factor score estimates (Ferrando & Lorenzo-Seva, 2016) and the usual simple sum scores. For the EAP scores, the marginal reliability estimate was .87. The conditional reliability (information) curve is presented in Figure 1 and is clear: the EAP scores demonstrate good accuracy to measure the low and medium trait levels with precision, but are unreliable at the upper end of the scale. Thus, the HHI would be a good instrument to detect individuals with low levels of hope, but would be less suitable for differentiating among those (the majority) that report high levels.

As for the raw or sum scores, the omega reliability estimate was .88, which again is acceptable for this relatively short test. The estimated fidelity coefficient was .97. These results indicate that the sum scores can be used as good proxies for measuring the Hope dimension. However, if the HHI scores are to be used for high stake testing or to establish cut-off values, then the IRT-EAP scores are preferable.

External Validity Evidence

The CFA solution above was extended to include four relevant external variables and fitted the data quite well: GFI = .982, RMSEA = .027, and NNFI = .970. All the standardized validity coefficients relating the hope construct to the external variables were statistically significant: resilience (β = .26), spiritually well-being (β = .29), meaning/ peace (β = .73), and faith (β = .44).

Discussion

This study examined the psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the HHI index both at the structural and at the measurement level. Structurally speaking, the results did not support the original 3-factor scale and instead suggested a dominant single-factor structure, similar to many other translations of the HHI (Geiser et al., 2015; Ripamonti et al., 2012; Rustøen et al., 2018; Soleimani et al., 2019), as well as the study conducted in the Spanish general population (Robles-Bello & Sánchez-Teruel, 2022). Moreover, the two negatively-worded items (#3 and #6) were very poor indicators of the construct. Previous studies suggest that reverse-coded items (and particularly negatively-worded items) might lead to structural issues such as those found here (Rustøen et al., 2018). In our opinion, well-designed, reverse-keyed items could work and, in fact, be useful to control response biases. However, the two negative items contained in the HHI clearly do not fulfill these purposes.

The CFA solution that was used to determine the structural validity of the HHI-Spanish version fitted well in all cases (single and multiple group) and the retained indicators had acceptable loadings. German, Norwegian, Persian, and Italian versions of the HHI have also established that a single-factor model adequately represented the structure of the HHI (Geiser et al., 2015; Ripamonti et al., 2012; Rustøen et al., 2018; Soleimani et al., 2019). Adapting a questionnaire to another culture can alter item meaning and inter-item relations, due to translation and cultural/ medical differences (Yaghoobzadeh et al., 2018). This is likely to account for why previous translations into other languages have produced very divergent factor solutions. In our study, this applies especially to the pair of items 1 and 2 and items 11 and 12, which have correlated errors. We believe that item 1, "I have a positive outlook on life" and item 11, "I believe every day has potential" in reference to the individual's ability to project into the future and understand the value of their existence, are highly metaphorical and would gain specific weight if reworded more concretely, such as item 1, “I have a positive attitude toward life” and item 11, “I believe that each day has potential.” These results demonstrate the using a scale in a culture other than the one it was originally designed for can potentially threaten the accuracy and reliability of the scale. This stems from the fact that the factors that affect the perception and evaluation of the concept of hope is not universal and can vary across cultures (Nayeri et al., 2020). This can open new avenues for future research to develop a new, culture-specific instrument to measure hope.

As for measurement invariance, strong invariance was attained in all the groups analyzed (gender, age, tumor site, and survival), thereby enabling both observed mean scores and latent estimated means to be validly compared. This study concurs with earlier works that also found scalar invariance on the basis of sex (Robles-Bello & Sánchez-Teruel, 2022). Nevertheless, as regards age, very young or very old individuals were found to interpret the HHI items dissimilarly in the Spanish sample (Robles-Bello & Sánchez-Teruel, 2022). This difference with respect to our series may be due to the mean age of our sample (65 years) and that they suffer a life-threatening disease. Likewise, we did not detect significant intergroup differences, probably because of the ceiling effect at the elevated hope constants in the sample. Some authors suggest that the physical and psychological discomfort resulting from the disease might negatively impact HHI scores (Austenå et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2020; Rustøen et al., 2018). The mean hope score in our series was analogous to Chinese (mean 40.5 ± 6.3) (Chen et al., 2020) and Norwegian (mean 37.4 ± 7.7) (Rustøen et al., 2018) individuals with cancer or patients in intensive care (mean 39.0 ± 5.0) (Austenå et al., 2023) and slightly higher than the Spanish population (mean 37.8 ± 6.2) (Robles-Bello & Sánchez-Teruel, 2022). In our series, the disease does not appear to have lowered the HHI scale scores, which could indicate that patients adapt and confront the difficulties of their illness maintaining hope.

Item and score functioning were appraised by means of IRT parameterization of the CFA solution. The marginal reliability of the scores was acceptable (ω = .88). The conditional reliability assessment, however, revealed that HHI is a good instrument to detect patients with low or intermediate levels of hope, but would be less accurate in distinguishing between those with high scores. The summed items may be a good proxy for the concept of hope in general; however, to set cut-off points, the CFA/ IRT score would be more accurate. One possible improvement of the scale would be to add more difficult items that would enable the higher levels to be accurately gauged.

Hope correlated with resilience and spiritual wellbeing (faith and meaning/peace). Other studies yielded similar results in which hope is associated with resilience (Calderon et al., 2022; Gronier et al., 2023; Sánchez-Teruel et al., 2020) and with spiritual wellbeing (Haugan et al., 2013). In the present study, the correlation between meaning/ peace and hope was relevant, whereas faith was not associated with a higher score on the hope scale. According to Pew-Forum, there is a sharp increase in secularism in countries such as Spain, Belgium, Finland, and Denmark compared to Italy or Portugal (Pew Research Center, 2018). This broad disparity in faith from one country to the next represents a challenge within a given group.

This study has several limitations that must be considered when reviewing and extrapolating the findings. While the large sample size was sufficient for the purpose of the study, further research might draw from a sample of different patient populations so as to compare groups of participants, to clarify the factor structure, and establish normative data. Moreover, all patients chose to participate voluntarily, which may have introduced some form of self-selection bias. Furthermore, the lack of test-retest reliability represents another limitation. Finally, it is possible that the results of our study may not be susceptible to extrapolation to individuals with resected cancer, whose clinical situation and prognosis differ appreciably.

The psychometric evaluation of the HHI scale in cancer patients carries practical and clinical implications. The scale can assist in identifying patients in need of support, tracking changes in hope levels, and customizing interventions based on individual needs. Its use can improve the quality of life and well-being for cancer patient.

To conclude, the findings from our study add to the existing body of knowledge regarding the construct of hope, as reported in earlier studies by (Geiser et al., 2015; Gronier et al., 2023; Robles-Bello & Sánchez-Teruel, 2022; Rustøen et al., 2018). The factor structure of the scale varies greatly among these studies, both in terms of the number of factors and the items that comprise the scale. Nevertheless, our results suggest that the Spanish version of the HHI, a brief, easily administered, 10-item scale, is both valid and reliable to quantify hope in patients with advanced cancer.