Introduction

The long competitive period in a futsal team schedule leads coaches and physical trainers to impose high training loads during the short pre-season to improve players’ performances.1,2) The high intensity demand imposed by futsal matches in addition to repeated sprints, abrupt stops, accelerations and changes of direction performed during the games3 require that players have well developed aerobic, anaerobic and neuromuscular systems. Previous studies reported that a short futsal pre-season (i.e., 3-9 weeks) improved performance in the Yo-Yo intermittent recovery (IR) test,2,4-6 VO2max,5 repeated-sprint ability,2 power of the lower limbs (i.e., inferred by vertical jump test) and speed1 of futsal players. However, only one of the aforementioned studies6 reported the magnitude of the training load worked (i.e., internal training load) and the effect of this training load on psychophysiological markers, as well as in physical performance tests. In this sense, it is difficult to establish whether the effect of pre-season on performance tests was amalgamated with fatigue accumulation.

It is well established that some tools are available to quantify training load and monitor respective training induced responses in high-level athletes. The session rating of perceived exertion (session-RPE) method is a simple, cheap and valid tool to monitor internal training load (ITL) in team sports and it is commonly used in monitoring futsal training.1,4,5,7,8 Similarly, the Recovery and Stress Questionnaire for Athletes (RESTQ)9 is a valid questionnaire often used to monitor stress and recovery in team sports.10-13 Biochemical variables, such as Creatine Kinase (CK), and hormonal variables such as testosterone and blood cortisol concentration are used to monitor muscle damage and disturbance in the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal and hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal axis, respectively; all of them indicators of fatigue accumulation.12,14,15 Thus, RESTQ, CK, testosterone and cortisol are potential indicators (markers) to be used for monitoring disturbances caused by fatigue accumulation in response to a futsal pre-season.

The Yo-Yo IR test is the most commonly used physical test to assess performance in team sports such as soccer and futsal2,4,6,16-18 and the YYIR2 actually seems to be more responsive to futsal training than the YYIR1.4 Hence, more studies reporting the behavior of the YYIR2 during the futsal training period are warranted. Power of lower limb is an important factor in decisive moments of futsal games such as kicking the ball at the goal, disputing the ball and counterattacking. Vertical jump (VJ) tests (i.e., squat jump (SJ); drop jump (DJ); countermovement jump (CMJ) tests) are physical tests frequently used to monitor changes in the physical capacity of futsal players.1,6 The different biomechanical, neuromuscular and elastic components involved in SJ, DJ and CMJ19,20 suggest that these tests can change differently in response to futsal training, indicating different adaptations in the neuromuscular system. However, to the best of our knowledge, the changes in the different VJ tests in response to specific futsal training have not yet been investigated.

Although knowledge about the behavior of psychophysiological markers and performance tests in response to the training load worked in pre-season could help coaches and physical staff to plan future training programs, physical performance and psychophysiological responses to a pre-season phase in high-level futsal players are still unclear. Thus, the main aim of this study was to verify the effects of a specific pre-season planning on physical performance, recovery-stress state and hormonal and muscle damage markers in high-level futsal players.

Method

Subjects

Fifteen male futsal players (age 28.4 ± 6.6 years, body mass 75.0 ± 6.6 kg; height 173.8 ± 5.2 cm; body fat 11.6 ± 3.7%), members of a high level Brazilian futsal team, participated in this study. After presentation of the study proposal and explanation of the possible risks involved in the process, players testified voluntary participation and authorized the use and disclosure of information. The study procedures were in accordance with the international standards of human experimentation (Declaration of Helsinki), and approved by the local ethics committee (protocol n° 2501.241.2011).

Experimental design

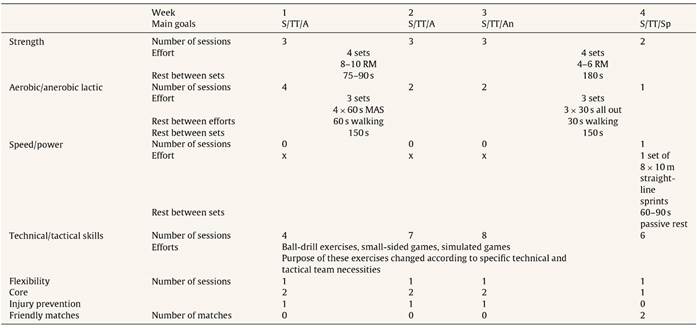

The futsal players returned from an off-season period during which physical activities were not controlled. The training program implemented during the pre-season phase was planned by team staff (Table 1). Before and after 4-weeks of pre-season, blood samples were collected, the RESTQ was applied, and vertical jump tests and YYIR2 were performed at 9:00 a.m. after 48 h without training sessions. Players were instructed not to ingest alcohol and caffeine for 24 h prior to data collection. Players performed 10 min of warm up before the physical performance tests, consisting of stretching and jogging at a comfortable pace. The ITL was measured in all training sessions using the Session-RPE method.7 Players were familiarized with the RPE scale, questionnaires and physical tests performed.

Table 1 Schedule of futsal pre-season.

A: aerobic; An: anaerobic lactic; MAS: maximal aerobic speed; Sp: speed; S: strength; TT: technical and tactical.

Blood collection was performed by a trained nurse, respecting the principles of biosecurity required. Five ml of blood were collected from the antecubital fossa arm vein, and stored in tubes with a gel separator and taken to the laboratory to be analyzed on the same day. For CK analysis, the blood sample was centrifuged for 5 min at 3200 rpm and the serum obtained was analyzed using specialized equipment (Biochemistry 3000 BT Plus® kit with Beckman Coulteur®). Testosterone and cortisol were analyzed using specific chemiluminescence tests, following the Bio System Kit specifications, according to the laboratory routine. The technique was developed by an Elecsys 2010 machine from Roche Diagnostics and the laboratory has a quality system certified by ABNT/INMETRO/ISO 9001/2000.

To carry out the vertical jump (VJ) tests an Ergojump carpet (Cefise®, Brazil) was used, with the analysis being performed using Jump System 1.0 software (Cefise®, Brazil). Three jump tests were performed in the following order: SJ, CMJ and DJ. For SJ, the athletes started in a squatting position with knees at approximately 90°, focusing only on the concentric phase of the movement. For CMJ, the athletes started in a standing position and then squatted and jumped at fast velocity to perform the jump with stretch-shortening cycle (SSC). The DJ started with the athlete in a standing position, at 40 cm above the Ergojump Carpet and the participants then squatted and jumped at fast velocity to perform the jump with SSC. The athletes were instructed to keep their hands on their waist. All players performed three trials for each jump test, with a 60 second interval between each attempt. The average of the best two performances was retained for analysis.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as mean and standard deviation. The data normality was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Repeated measure ANOVA was used to compare the TWTL between different weeks. To compare the differences between pre- and post-training of all other dependent variables (except the RESTQ scales) the Student's t-test and the magnitude based inference (MBI)21 were used, from which the smallest worthwhile change (i.e., 0.2×standard deviation) and 90% confidence intervals were also determined. The qualitative ranking utilized was: < 1%, almost certainly not; 1-5%, very unlikely; 5-25%, unlikely; 25-75%, possible; 75-95%, likely; 95-99%, very likely; > 99%, almost certain. If the positive and negative result values were both > 5% the results were deemed as unclear. The MBI analyzes were conducted using a spreadsheet posted on the web-site http://www.sportsci.org/resource/stats/.SPSS software, version 20.0 was used for all analyses.

Results

The TWTL of the four pre-season weeks is shown in Fig. 1. The TWTL of the first week was lower than that of the third week, and the TWTL of the fourth week was lower than in the other three weeks (p < 0.01).

The performance in the YYIR2 and SJ tests increased after pre-season (p < 0.01), however the CMJ and DJ did not change with training (p ≥ 0.05). MBI analyzes demonstrated that the chances of SJ, CMJ, DJ and YYIR2 improving with training were very likely, possible, unlikely, almost certain, respectively (Table 2). The CK, testosterone and testosterone/cortisol ratio (T/Cr) increased, and cortisol decreased in response to pre-season training (p < 0.01). The MBI analyzes showed that the chances of testosterone, cortisol, T/Cr and CK changing with training were possible, very likely, almost certain and almost certain, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2 Changes in performance in physical tests and in biochemical variables during pre-season training.

| Physical tests | Pre-season | Post-season | p-Value | MBI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SJ (cm) | 36.31 ± 4.08 | 39.01 ± 4.47 | 0.01* | 98/2/0 |

| CMJ (cm) | 40.11 ± 4.73 | 41.13 ± 5.38 | 0.05 | 56/44/0 |

| DJ (cm) | 38.33 ± 4.75 | 38.21 ± 5.41 | 0.84 | 4/88/8 |

| YYIR2 (m) | 573.33 ± 193.42 | 762.67 ± 211.37 | < 0.01* | 100/0/0 |

| Testosterona (pgml−1) | 14.43 ± 1.62 | 14.78 ± 1.43 | < 0.01* | 58/42/0 |

| Cortisol (μgml−1) | 18.11 ± 4.17 | 14.61 ± 3.64 | < 0.01* | 0/1/99 |

| T/Cr | 0.85 ± 0.25 | 1.08 ± 0.33 | < 0.01* | 100/0/0 |

| CK (UL−1) | 221.00 ± 101.35 | 433.20 ± 259.81 | < 0.01* | 100/0/0 |

CMJ: Countermovement jump; CK: creatine kinase; DJ: drop jump; MBI: magnitude based inference; SJ: squat jump; T/Cr: testosterone/cortisol ratio; YYIR2: Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test Level 2.

*Post-training better than pre-training (p < 0.05).

The RESTQ scales “general stress, social stress, lack of energy, physical recovery and sleep quality” did not change and the “social recovery and general well-being” scales decreased with training. All others RESTQ scales were higher after the training program (p < 0.05) (Figs. 1 and 2).

Discussion

The main results found in the present study were that the futsal pre-season improved performance in the YYIR2 and SJ tests. The improvement in performance tests was accompanied by an increase in testosterone, CK, T/Cr and in the majority of the RESTQ scales. Cortisol and the social recovery and general well-being RESTQ scales decreased during the futsal pre-season.

The ITL monitored during the futsal pre-season in the present study increased during the first three weeks and decreased in week fourth. Intensification of the ITL followed by a period of decrease has been reported previously in team sports.12,14,15,22 This training load distribution provides a moment of fatigue accumulation, and, consequently, worsening performance in physical tests14,15 which is followed by supercompensation and improving performance in physical tests.14,15,22 The improvement in physical tests, in response to training load distribution, demonstrated in the present study is in accordance with the aforementioned studies.14,15,22

The supercompensation phenomena reported above is a possible explanation for the higher values in the YYIR2 (∼35%) found in the present study, compared with ∼25% improvement previously reported in futsal and soccer players after a period of training.4,18 Furthermore, the high intensity characteristics of futsal training and matches, with a large contribution from the aerobic and anaerobic system, justify the improvement in the YYIR2.3,4 The SJ was the only neuromuscular test that significantly changed in response to the futsal pre-season. The strength training, accelerations, and other actions involved in futsal training could be responsible for the improvement in SJ in the present study as previously reported in female basketball players.22 The stress RESTQ scales (i.e., Emotional stress, conflict/pressure, fatigue, physical complaints, disturbed breaks, emotional exhaustion and injuries) increased and the recovery scales (i.e., social recovery and general well-being) decreased in response to the futsal pre-season. Furthermore, in the present study, some recovery scales (i.e., being in shape, personal accomplishment, self-efficacy and self-regulation) increased with training, suggesting that the futsal pre-season positively changed the sport specific recovery scales.

The level of increase in CK blood concentration found in the present study (i.e., 221.0-433.2 UL−1) was lower than the level reported in previous studies (i.e., ∼400 to ∼1300 UL−1) in which CK was associated with decreased performance in physical tests.14,15 Despite an increase in CK blood concentration, players improved their performance in the YYIR2 and SJ tests. A similar increase in CK blood concentration (i.e., ∼180 to ∼580 UL−1) was not associated with changes in performance in the CMJ test in volleyball players after a period of training load intensification.12 Possibly the small increase in CK reported in the present study is a physiological behavior in futsal players and does not impact on performance in physical tests. Changes in cortisol and testosterone blood concentration reflecting in a decrease in T/Cr have been reported in athletes with symptoms of fatigue accumulation.14,15 However, the results found in the present study showed that cortisol decreased, while testosterone and T/Cr increased in response to a futsal pre-season. Since cortisol is a catabolic and testosterone an anabolic hormone,23 the results found suggest that the futsal pre-season promoted an anabolic environment in the players analyzed.

In summary, players improved their performance in the YYIR2 and SJ tests in response to a futsal pre-season. Despite possible improvement in the CMJ test, the futsal pre-season, without explosive training, did not promote large changes in this variable. Furthermore, the ITL behavior of the futsal training in the present study promoted a favorable hormonal anabolic environment and did not promote a negative disturbance in CK or stress/recovery balance (i.e., RESTQ scales), suggesting that futsal players did not report fatigue accumulation after a pre-season composed of three weeks of accumulated ILT followed by one week of decreased ITL. The results found in the present study suggest that coaches and physical trainers could use an ITL distribution similar to that used in the present study aiming to improve performance in physical tests without increasing fatigue accumulation markers. Furthermore, the training load application should be accompanied by frequent monitoring of the physical performance and psychophysiological markers to ensure that the ITL distribution is appropriate to different futsal players.