In the past few decades, societies have been alarmed about increasing violent and aggressive behaviors in adolescents. The World Health Organization (WHO) warns that violence is a global threat to public health. Unfortunately, despite the efforts of public authorities to eradicate the high ratios of aggressive behaviors in young people, this pandemic public health concern still remains (WHO, 1996, 2009, 2014; see also Baron & Richardson, 1994). Research has exhaustively examined aggression as behavior and aggressiveness as an individual disposition for aggressive behavior (e.g., the desire to start fights with others; for a review, see Wahl & Metzner, 2012).

Aggressiveness among adolescents is one of the most consistent and strongest predictors of a wide range of health problems, such as antisocial behavior, difficulties with cognitive abilities, and internalizing and externalizing harmful behaviors (Chermack & Giancola, 1997; Dodge, Price, Bachorowski, & Newman, 1990; Donnellan, Trzesniewski, Robins, Moffitt, & Caspi, 2005; Racz, Putnick, Suwalsky, Hendricks, & Bornstein, 2017). For example, aggressive adolescents report lower self-esteem (Donnellan et al., 2005), take more drugs (Chermack, & Giancola, 1997), or even have more mental disorders (Dodge et al., 1990). Furthermore, aggressive adolescents are more involved in neighborhood violence (Gracia, Fuentes, García, & Lila, 2012), intimate partner violence (Moretti, Obsuth, Odgers, & Reebye, 2006), bullying (Ayers, Wagaman, Geiger, Bermudez-Parsai, & Hedberg, 2012), child-to-parent violence (Gallego, Novo, Fariña, & Arce, 2019), and dating violence (Morris, Mrug, & Windle, 2015). Aggressiveness is not only limited to adolescence. Empirical evidence suggests that aggressiveness and certain forms of aggression arise early, with some degree of continuity of general aggressiveness from childhood and adolescence to adulthood (Wahl & Metzner, 2012).

Aggressive behavior has been shown to be strongly linked to peers’ social influences, broad social and contextual factors, cultural approval of violence, or even a genetic predisposition, although parents are among the strongest influences on the development of aggressiveness in young people (Garcia, Lopez-Fernandez, & Serra, 2018; Moffitt, 2018; Raine, 2002). Many parenting studies generally identify two main orthogonal (i.e., unrelated) dimensions (responsiveness and demandingness, also called warmth/acceptance/involvement and strictness/imposition) and four parenting typologies (i.e., authoritative, indulgent, authoritarian, and neglectful). Importantly, the four-typology or quadripartite model stresses the need to consider the combination of the two parenting dimensions in the analysis of the relationships between parenting and youth outcomes (e.g., Lamborn, Mounts, Steinberg, & Dornbusch, 1991). By contrast, some traditional studies have been criticized for ignoring variations in warmth in families characterized by strictness (i.e., authoritative and authoritarian) (Kerr & Stattin, 2000; Stattin & Kerr, 2000). For example, an ambiguous conceptualization of monitoring as a parenting practice involving active attempts by parents to watch over children as a resource for firm control or strictness is certainly associated with a wide range of positive adolescent outcomes. However, researchers have noted that most of this relationship can be explained by adolescents’ spontaneous revelation of information to parents (authoritative), rather than by parents’ attempts to obtain secure information (authoritarian) (Ahn & Lee, 2016; Calafat, Garcia, Juan, Becoña, & Fernandez-Hermida, 2014; Valente, Cogo-Moreira, & Sanchez, 2017).

The parenting style represents the family emotional context where parents try to achieve their main socialization objectives, such as demanding maturity, respecting the social norms, or avoiding harming other people (Darling & Steinberg, 1993). Authoritarian parents (non-warmth but strictness) demand obedience to rules and use the regular imposition of strict rules, but they offer parenting environments that are cold, distant, and limited to unidirectional communication. While authoritative parents (warmth and strictness) share this same obedience to rules and also use regular imposition of strict rules, it is conceptually different from authoritarian parenting because these parents use bidirectional communication and reasoning with their children (Lewis, 1981; Baumrind, 1983). Thus, although both authoritative and authoritarian parenting styles share the same strictness and imposition, only authoritative parents treat their children in a rational and flexible way, taking advantage of bidirectional open communication and reasoning (García & Gracia, 2014; Grusec, Danyliuk, Kil, & O’Neill, 2017; Martinez, Cruise, Garcia, & Murgui, 2017; Martinez, Garcia et al., 2019).

Indeed, a large body of cumulative empirical evidence has demonstrated that parenting styles (i.e., authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful) are differentially associated with positive or negative impacts on developmental outcomes, including a child’s aggressiveness. Overall, research findings in Anglo-Saxon contexts with mainly European-American samples have consistently reported that children and adolescents raised in authoritative households (warmth and strictness) have better developmental outcomes than their peers raised in authoritarian (strictness but not warmth), indulgent (warmth but not strictness), or neglectful (neither warmth nor strictness) households (Baumrind, 1967, 1971; Lamborn et al., 1991; Steinberg, 2001; Steinberg, Blatt-Eisengart, & Cauffman, 2006; Steinberg, Lamborn, Darling, Mounts, & Dornbusch, 1994). Specifically, in the field of aggressiveness, the authoritative style has been related to the lowest levels of both physical and relational aggression (for a review, see Kawabata, Alink, Tseng, van IJzendoorn, & Crick, 2018). The parental component of strictness/imposition (common in authoritative and authoritarian parents) may help parents to obtain obedience and conformity with the social standards from their children, whereas lack of strictness/imposition is related to higher rates of deviance and aggression.

Nevertheless, many studies across different ethnicities, environments, and societies have questioned the idea that the authoritative parenting style is always associated with the optimal adjustment outcomes in children and adolescents (Baumrind, 1972; Clark, Yang, McClernon, & Fuemmeler, 2015; Darling & Steinberg, 1993; García & Gracia, 2009, 2014). On the one hand, early findings from US ethnic minority groups (Baumrind, 1971), poor families (Hoff, Laursen, & Tardif, 2002), low-educated parents (Leung, Lau, & Lam, 1998), Middle Eastern groups such as Arabs (Dwairy, Achoui, Abouserie, & Farah, 2006), and Asian societies (Quoss & Zhao, 1995) indicated that the authoritarian parenting style (which shares strictness with the authoritative parenting style) is associated with some positive outcomes (Baumrind, 1967, 1971; Chao, 1994, 2001; Darling & Steinberg, 1993; García & Gracia, 2009; Steinberg et al., 1994). For example, Chao (1994, 2001) found that Chinese American children from authoritarian families obtained better academic results than their counterparts from authoritative families. Quoss and Zhao (1995) reported that Chinese children with authoritarian parents, but not authoritative, were associated with satisfaction with the parent-child relationship. Because people adjust better and are more satisfied in environments that match their attitudes, values, and experiences (see García & Gracia. 2009), in poor ethnic minority families and dangerous communities, authoritarian parenting may not be as harmful and may even have some protective benefits (Furstenberg, Cook, Eccles, Elder & Sameroff, 1999; Steinberg et al., 2006).

On the other hand, findings from emergent research in European and Latin American countries have also pointed out that the indulgent parenting style (warmth but non-strictness) provides equal or even better benefits than the authoritative parenting style (warmth and strictness) (Calafat et al., 2014; García & Gracia, 2009, 2010; Di Maggio & Zappulla, 2014; Martinez & Garcia, 2007, 2008; Rodrigues, Veiga, Fuentes, & Garcia, 2013; Valente et al., 2017). Adolescents from indulgent families had the same or better scores on outcomes such as self-esteem (Fuentes, Garcia, Gracia, & Alarcon, 2015; Garcia & Serra, 2019; Garcia, Serra, Zacares, & Garcia, 2018; Riquelme, Garcia, & Serra, 2018; Rodrigues et al., 2013) and psychological health adjustment (Calafat et al., 2014; García & Gracia, 2009, 2010; Garcia, Serra, Zacares, Calafat, & Garcia, 2019). In addition, indulgent parenting provides benefits against deviance. Adolescents from indulgent families reported low aggressiveness (García & Gracia, 2009, 2010; Moreno-Ruiz, Estévez, Jiménez, & Murgui, 2018; Suárez-Relinque, Arroyo, León-Moreno, & Jerónimo, 2019). Currently, Calafat et al. (2014), in a comparison study of six European countries (including Sweden and the United Kingdom), found that children from indulgent parenting homes obtained better self-esteem and school performance, even better than children from authoritative parenting style homes. Recent emergent research indicates that strictness, firm control, and impositions in the socialization practices seem to be perceived in a negative way, and more attention might be placed on the use of warmth, emotional support of the child, and involvement in children’s socialization (García & Gracia, 2009, 2014; Grusec et al., 2017; Martinez & Garcia, 2007, 2008; White & Schnurr, 2012). Additionally, some current findings identify the indulgent parenting style as the optimum for the current “digital society” in different environments and context, as for example adolescents from middle-class families of United States (Garcia, Serra, Garcia, Martinez, & Cruise, 2019).

The Present Study

An important question is whether the ways parents raise their children (e.g., parenting practices or parenting styles) have the same or different effectiveness for aggressive children and non-aggressive children. Underlying this unanswered question is the issue of whether the benefits of optimal parenting transcend the boundaries of children’s individual characteristics, such as their predisposition to aggressiveness. The empirical evidence available does not offer clear conclusions.

Although some studies have examined the impact of parental practices on aggressive adolescents, the results are not consistent. Most of these studies used clinical samples rather than community samples, or tested the effectiveness of interventions targeting the family. On the one hand, warm, affective, responsive, and inductive parenting (common in indulgent and authoritative parents) tends to help aggressive children to adjust better to the social standards (Pinquart & Kauser, 2018). Nevertheless, other studies found parental acceptance and warmth to be a risk factor in aggressive children, who were not able to anticipate and understand the consequences of social behaviors and select the appropriate means to achieve their goals (Ruiz-Ortiz, Braza, Carreras, & Muñoz, 2017). On the other hand, some studies suggest that parental monitoring (e.g., setting rules and restrictions for children) is not a significant protective factor against adolescent aggression (Law, Shapka, & Olson, 2010) or significantly associated with child-to-parent violence (Beckmann, Bergmann, Fischer, & Mößle, 2017), or even that harsh parenting could exacerbate aggressiveness in adolescents (Tung & Lee, 2018). However, other studies suggest that lack of strictness and imposition may be a main risk factor related to the aggressive tendency (Furstenberg et al., 1999).

Additionally, some gender scholars have pointed out the gap between parenting practices of warmth and strictness and their different impact on males and females, raising doubts about whether parents should act differently with their sons than with their daughters in order to prevent deviance (Bully, Jaureguizar, Bernaras, & Redondo, 2019; Carlo, Raffalli, Laible, & Meyer, 1999; Griffin, Botvin, Scheier, Diaz, & Miller, 2000; Hosokawa & Katsura, 2018). For example, parental warmth was found to be a protective factor against child-to-parent violence in females but not in males (Beckmann et al., 2017), unsupervised time at home alone (low strictness) was associated with more smoking only for females (Griffin et al., 2000), and lack of parental discipline (low strictness) was related to aggression and other externalizing behavioral problems in males, but not in females (Hosokawa & Katsura, 2018).

Less attention has been paid to parenting styles. Some previous studies have examined the parenting styles for juvenile offenders (Steinberg et al., 2006) or adolescents with an antisocial tendency (Garcia, Lopez-Fernández et al., 2018), but without analyzing the increasingly common situation of having an adolescent child with a predisposition to aggression. Particularly, in the European and South American cultural context there are doubts about whether the indulgent style (warmth but not strictness) could be the optimal parenting style in families with aggressive children. It has been widely demonstrated in the literature that aggressive children have the poorest psychological competence and consistently lower adjustment on several outcomes (e.g. Martinez, Murgui, Garcia, & Garcia, 2019; Moreno-Ruiz, Martínez-Ferrer, & García-Bacete, 2019). Aggressive children are more likely to misunderstand and not internalize the social values (Blair, 1997). Because the main way to get children to internalize the social values is through reasoning and bidirectional communication between parents and children (shared indulgent and authoritative parenting styles), some parenting styles might not be effective due to lack of bidirectional child-parent communication (Álvarez-García, Núñez, García, & Barreiro-Collazo, 2018; Ruiz-Hernández, Moral-Zafra, Llor-Esteban, & Jiménez-Barbero, 2019).

However, parenting literature claims that the relation between parenting styles and the patterns of children adjustment and competence are consistent across child age and sex, despite the multiple differences that have been established in different aspects of developmental adjustment depending on age and sex (i.e., sex- and age-related differences). For example, females show better academic and emotional self-esteem but less physical self-esteem than males, whereas males tend to have higher emotional maladjustment (e.g. emotional irresponsiveness or emotional instability). In a similar way, studies with adolescents describe age-related reductions in self-esteem and increases in psychological maladjustment (Garcia & Serra, 2019; Garcia et al., 2019; Martinez, García et al., 2019; Riquelme et al., 2018).

The present study examines the relationship between parenting styles (i.e., authoritative, indulgent, authoritarian, and neglectful) and adolescent aggressiveness, and the socialization pattern outcomes through self-esteem (physical, family, and emotional) and personal maladjustment (negative self-esteem, negative self-adequacy, emotional irresponsiveness, emotional instability, and negative worldview). Based on the literature review, we can hypothesize: first, that aggressive children will be associated with the poorest psychological adjustment; second, that indulgent and authoritative parenting styles will be associated with the best outcomes, whereas neglectful and authoritarian parenting styles will be associated with the poorest psychological adjustment. We expect that these hypotheses will be consistent, irrespectively of the sex and age of the participants.

Method

Participants and Procedure

In the present study, participants were 969 adolescents, 415 males (42.8%) and 554 females (57.2%), ranging from 12 to 17 years old (M = 14.93 years old, SD = 1.75 years old). A priori statistical power analysis indicated a minimum sample of 880 participants for a power of 0.95 (α = .05, 1 - β = .95) to detect a medium-small effect size (f = .14), estimated in the ANOVAS by Lamborn et al. (1991), in a univariate F test of the four parenting styles (Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner, & Lang, 2009; García, Pascual, Frías, Van Krunckelsven, & Murgui, 2008; Pérez, Navarro, & Llobell, 1999; Veiga, García, Reeve, Wentzel, & García, 2015). A sensitivity statistical power analysis indicated that a sample size of 969 students is able to detect an effect size near .13 (f = .133, α = .05, 1 - β = .95). The data were obtained from high schools in the Valencian region selected by simple sampling from the complete list of schools. To obtain the students, we contacted the heads of nine public and private high schools in the Valencian Region (two of them refused to participate). Parental approval (98% share) was obtained from the participants, and the questionnaires were administered during class time. All the participants reported that their four grandparents were Spanish. This study follows principles included in the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the research ethics committee of the Program for the Promotion of Scientific Research, Technological Development, and Innovation of the Valencian Region, which supported this research.

Measure Instruments

Parenting styles. Parental warmth was measured with a 20-item Warmth/Affection Scale (WAS; Rohner, Saavedra, & Granum, 1978). This measure assesses parents’ tendency to be loving, responsive, and involved. Sample items are: “Talk to me in a warm and loving way” and “Make me feel what I do is important”. Responses are given on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (always). Higher scale scores indicate higher levels of parental warmth. Cronbach’s alpha in this study was .918. Parental strictness was measured with the 13-item Parental Control Scale (PCS; Rohner, 1989; Rohner & Khaleque, 2003). This scale assesses parents’ tendency toward strict parental control of their children’s behavior. Sample items are: “Insist that I do exactly as I am told” and “They believe in having a lot of rules and sticking to them”. Responses are given on a 4-point Likert-type scale that ranges from 1 (never) to 4 (always). Higher scale scores indicate higher levels of parental strictness. Cronbach’s alpha in this study was .805. As in previous studies (e.g., García & Gracia, 2009; Lamborn et al., 1991), the four parenting styles were established by the median split procedure for warmth and strictness, examining both parental dimensions at the same time: authoritative style (above median on both warmth and strictness), indulgent style (above the median on warmth, but below on strictness), authoritarian style (above the median on strictness, but below on warmth), and neglectful style (below the median on both parental dimensions).

Aggressiveness was measured with the 6-item Hostility/Aggression Scale (Personality Assessment Questionnaire; Rohner, 1990). A sample item is: “I get so mad I throw or break things”. Adolescents responded on a 4-point Likert-type scale that ranges from 1 (never) to 4 (always). Higher scale scores indicate higher aggressiveness. Cronbach’s alpha in this study was .672. The low aggression group consisted of those who scored below the 50th percentile, and the high aggression group consisted of those who scored above the 50th percentile.

Self-esteem was measured with three 6-item subscales of the Multidimensional Self-Esteem Scale (Form 5) (García & Musitu, 1999). For emotional self-esteem, a sample reverse-scored item is “I am afraid of some things”, a physical self-esteem sample item is “I take good care of my physical health”, and a family self-esteem sample item is “My family would help me with any type of problem”. Responses are given on a 99-point scale that ranges from 1 (strong disagreement) to 99 (strong agreement). Higher scale scores indicate higher levels of the respective self-esteem dimension. Cronbach’s alphas in this study were: emotional, .710, physical, .848, and family, .713. AF5 is one of the most extensively used self-esteem instruments with Spanish-speaking samples (Fuentes, García, Gracia, & Lila, 2011; García, Gracia, & Zeleznova, 2013; Maiz & Balluerka, 2018). Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis supported a multidimensional factorial structure (García & Musitu, 1999; García et al., 2013; García, Martínez et al., 2018; Murgui, García, García, & García, 2012), and no method effects were associated with negatively worded items (García, Musitu, Riquelme, & Riquelme, 2011).

Psychological adjustment was measured with five 6-item subscales of the PAQ (Personality Assessment Questionnaire; Rohner, 1978): (i) a negative self-esteem sample item is “I feel I am no good and never will be any good by others”; (ii) a negative self-adequacy sample item is “I feel I can do the things I want as well as most people”; (iii) an emotional irresponsiveness sample item is “I have trouble showing people how I feel”; (iv) an emotional instability sample item is “I feel bad or get angry when I try to do something and I cannot do it”; and (v) a negative worldview sample reverse-scored item is “I feel that life is nice”. Responses are given on a 4-point Likert-type scale that ranges from 1 (never) to 4 (always). Higher scale scores indicate higher levels of the respective psychological maladjustment dimension. Cronbach’s alphas in this study were: negative self-esteem, .733, negative self-adequacy, .687, emotional irresponsiveness, .736, emotional instability, .718, and negative worldview, .847.

Data Analysis

It was applied a full multivariate factorial analysis of variance (MANOVA) for the outcomes of self-esteem (academic and emotional), psychological maladjustment (hostility/aggression, negative self-esteem, negative self-efficacy, emotional irresponsibility, emotional instability, and negative worldview), and academic achievement (grade point average and number of failing grades). Independent variables formed a full factorial design (4 × 2 × 2 × 2) with the parenting style (neglectful, indulgent, authoritarian, and authoritative), aggressiveness (low vs. high), sex (male vs. female), and age (12-15 vs. 16-17 years) factors. Univariate F-tests were applied and univariate sources of variation that were statistically significant in the MANOVA were examined. Finally, the post-hoc Bonferroni was applied to control the rate of Type I error.

Results

Parenting Style Groups

Table 1 provides information about the size of each of the four parenting groups as well as each group’s means and standard deviations on the two main parental dimension measures: warmth and strictness. In line with the parenting model orthogonality assumption, additional analyses showed that the two measures of parental dimensions, warmth and strictness, were uncorrelated, r = -.034, R2 = .009, p = .288, the distribution of families by parenting style groups was homogeneous, X2(3) = 3.24, p = .356, and no interactions were found between sex and parenting style, X2(3) = 4.96, p = .175.

Overall Effects of Parenting Styles, Aggressiveness, Sex, and Age on Adolescent Self-esteem and Psychological Maladjustment

The results of the MANOVA (Table 2) showed significant differences in the main effects of parenting style, ∧ = .723, F(24, 2697.9) = 13.28, p < .001, aggressiveness, ∧ = .807, F(8, 930.0) = 27.78, p < .001, sex, ∧ = .899, F(8, 930.0) = 13.03, p < .001, and age, ? = .955, F(8, 930.0) = 5.42, p < .001, and statistically significant interaction effects for parenting style by aggressiveness, ∧ = .950, F(24, 2697.9) = 1.99, p = .003, aggressiveness by age, ∧ = .982, F(8, 930.0) = 2.10, p = .033, and sex by age, ∧ = .981, F(8, 930.0) = 2.31, p = .019. Neither other interactions were statistically significant (α = .05) (see Table 2).

Table 2. Four-way MANOVA Factorial 4 × 2 × 2 × 2 for Outcome Measures of Self-esteem and Psychological Maladjustment

Note.1∧ estimated the proportion of variance not explained, i.e., 1 – ∧ = η2 (Tatsuoka, 1971); 2a1, neglectful, a2, indulgent, a3, authoritarian, a4, authoritative; 3b1, low, b2, high; 4c1, male, c2, female; 5d1, 12-15 years, d2, 16-17 years.

Study of the Parenting and Aggressiveness Effects on Self-esteem

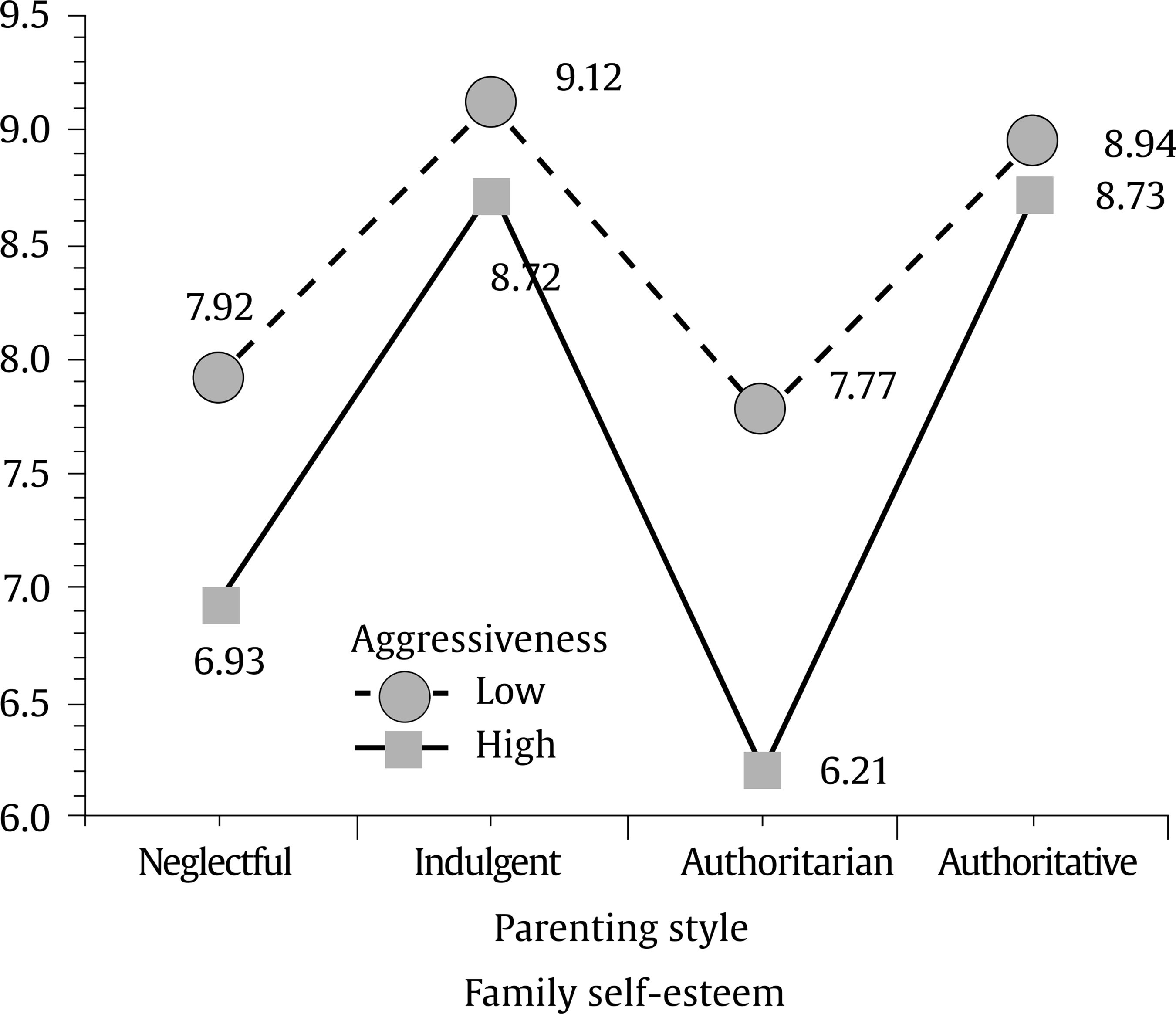

Results confirmed the first hypothesis about the self-esteem dimensions (Table 3). Aggressive adolescents reported lower family and emotional self-esteem than non-aggressive adolescents. As it was secondly hypothesized, adolescents from indulgent and authoritative families reported more physical and family self-esteem than those from neglectful and authoritarian homes. Specifically, on family self-esteem, interaction effects were found, F(3, 937) = 9.11, p < .001, f = .166 (see Figure 1). A similar parenting profile is drawn. Again, indulgent and authoritative parenting styles were associated with higher family self-esteem than authoritarian and neglectful parenting. However, only in warm families (indulgent and authoritative), both aggressive and non-aggressive adolescents reported the highest scores (no differences were found between them). By contrast, in families characterized by lack of warmth (authoritarian and neglectful), aggressive adolescents reported lower family self-esteem than non-aggressive adolescents. On emotional self-esteem, adolescents from indulgent homes obtained better scores than their counterparts from authoritative families, whereas those from authoritarian and neglectful families reported the lowest emotional scores.

Table 3. Means and Standard Deviations, Main Univariate F Values, Effect Size f, Probabilities of Type I error, and Bonferroni Test for Outcome Measures of Self-esteem and Psychological Maladjustment based on Parenting Style and Aggressiveness

Note.Effect size conventions: f = .10, small; f = .25, medium; f = .40, large. Eta squared = f ^ 2 / 1+ f ^ 2 (Faul et al., 2009). Bonferroni test α = .05; 1 > 2 > 3 > 4; a > b. *p < .05, **p < .01, **p < .001; ns = non significant.

Study of the Parenting and Aggressiveness Effects on Psychological Maladjustment

Results confirmed the first hypothesis in the psychological maladjustment dimensions (Table 3). Aggressive adolescents reported more negative self-esteem, negative self-adequacy, emotional irresponsiveness, and emotional instability, and a more negative worldview than non-aggressive adolescents. Additionally, an aggressiveness by age interaction effect was found on negative self-adequacy, F(1, 937) = 3.92, p = .048, f = .064 (see Figure 2). A similar pattern was found. Thus, aggressive adolescents reported higher scores than non-aggressive adolescents. However, only aggressive 16-17 year-old adolescents reported more negative self-adequacy than their 12-15 year-old peers. Results confirmed the second hypothesis. Indulgent and authoritative parenting styles were related to the best results on psychological maladjustment outcomes. Adolescents from indulgent and authoritative families reported lower psychological maladjustment scores (negative self-esteem, negative self-adequacy, emotional irresponsiveness, emotional instability, and negative worldview) than those from neglectful and authoritarian families.

Study of Sex and Age Effects on Self-esteem and Psychological Maladjustment

Although not central to this study, several main effects of sex and age reached significance (see Table 4). Regarding the self-esteem outcomes, results indicated that physical and emotional self-esteem scores were higher in males, whereas physical self-esteem scores were higher in the youngest adolescents (12-15 years old). An interaction effect between sex and age was found on family self-esteem, F(1, 937) = 4.16, p = .042, f = .066 (see Figure 2). A decreased tendency related to age was found (16-17 year-old adolescents reported lower scores than their 12-17 year-old peers), but this tendency was more pronounced in males. Regarding psychological maladjustment outcomes, females reported higher self-adequacy and emotional instability, but less emotional irresponsiveness, than males. Age-related differences showed that negative self-esteem, emotional irresponsiveness, and emotional instability scores were always highest in 16-17 year-old adolescents.

Table 4. Means and Standard Deviations, Main Univariate F Values, Effect Size f, Probabilities of Type I Error, and Bonferroni Test for Outcome Measures of Selfesteem and Psychological Maladjustment by Sex and Age Groups

NoteEffect size conventions: f = .10, small; f = .25, medium; f = .40, large. *p < .05, **p < .01, **p < .001; ns = non significant.

Discussion

The present study tested whether the correlates of the parenting styles (i.e., indulgent, authoritative, authoritarian, and neglectful) with competence and adjustment are the same for aggressive adolescents and non-aggressive adolescents. The competence and adjustment of the adolescents were captured through self-esteem (physical, family, and emotional) and psychological maladjustment (negative self-esteem, negative self-adequacy, emotional irresponsiveness, emotional instability, and negative worldview). Overall, regardless of adolescents’ aggressiveness, results showed the benefits of parental warmth (shared by indulgent and authoritative parents), whereas lack of parental warmth (common in authoritarian and neglectful families) was related to poor adjustment and competence. Nevertheless, aggressive and non-aggressive adolescents from indulgent, authoritative, authoritarian, and neglectful families showed different patterns in their family self-esteem.

Results for the main effects indicated that adolescent aggressiveness was related to the worst outcomes: poor self-esteem and greater psychological maladjustment. Regarding main effects for parenting styles, results showed that indulgent parenting was related to equal (on physical and family self-esteem, as well as on psychological maladjustment) or even better results (on emotional self-esteem) than authoritative parenting. By contrast, authoritarian and neglectful parenting were associated with the poorest self-esteem and the greatest psychological maladjustment. However, an interaction effect between parenting style and aggressiveness was found on family self-esteem. Interestingly, aggressive adolescents indicated the highest family self-esteem in the same way as non-aggressive adolescents, although this pattern was only found in warm families (indulgent and authoritative). However, in authoritarian and neglectful families, both aggressive and non-aggressive adolescents showed poor family self-esteem (but the lowest family self-esteem corresponded to aggressive adolescents).

One of the most crucial findings of the present study is that, for both aggressive and non-aggressive adolescents, the use of reasoning and warmth shared by both parental warmth families (indulgent and authoritative) is the main way to obtain well-adjusted adolescents with good self-esteem and low psychological maladjustment. By contrast, lack of parental warmth is a risk factor. Authoritarian (strictness but not warmth) and neglectful (no warmth or strictness) parenting styles are constantly related to poor adolescent outcomes. Therefore, the present results confirm previous findings in some European and South American countries (e.g., Calafat et al., 2014; Garcia & Gracia, 2009, 2010, 2014; Martínez, García, Musitu, & Yubero, 2012; Garcia & Serra, 2019; Valente et al., 2017), extending results from previous studies to aggressive adolescents. Nevertheless, the present findings clearly contrast with some previous studies that analyzed parenting styles and adolescent deviance (a failure of the parenting socialization process because children are not able to fit social standards). Overall, our results suggest that the strictness component does not seem to be necessary (adolescents from indulgent families perform equally well or even better than their peers from authoritative homes), and could be harmful for adolescent development (authoritarian parenting is related to poor results). Specifically, our results indicated that adolescents from authoritarian families have lower self-esteem and greater psychological maladjustment. However, previous research conducted mainly in Anglo-Saxon countries (Lamborn et al., 1991; Steinberg et al., 1994) suggests some benefits of authoritarian parenting based on the idea that the strictness and imposition component, common in authoritative and authoritarian families, emerges as the main deterrent of deviance. Adolescents with authoritarian parents do well on obedience and conformity to adult standards (see Lamborn et al., 1991, p. 20).

Another crucial finding from this study is the different impact of the parenting style on family self-esteem as a function of adolescent aggressiveness. Overall, in the present study, aggressive adolescents report worse self-esteem and greater psychological maladjustment than those who are not aggressive on eight of the nine developmental outcomes, confirming previous studies about the general lack of adjustment and competence among aggressive adolescents (Chermack, & Giancola, 1997; Dodge et al., 1990; Racz et al., 2017). In the same way, although one might expect aggressive adolescents to report lower family self-esteem than non-aggressive adolescents, our findings suggest that family self-esteem could be different in aggressive and non-aggressive adolescents depending on their family typology. Remarkably, aggressive adolescents have the same optimal family self-esteem as their non-aggressive peers from warm families (i.e., indulgent and authoritative), and even better than non-aggressive adolescents from lack of warmth families (i.e., authoritarian and neglectful).

Therefore, some important implications for parents and society can be drawn. Although clinical interventions for aggressive adolescents highlight that families should develop a strong protective role, one difficulty for clinical success is that aggressive adolescents experience a diminished sense of self in the family domain. Families characterized by warmth, involvement, and the use of reasoning and bidirectional communication may act as a buffer for family self-esteem in the presence of adolescent aggressiveness. Future studies should examine mechanisms that may be involved in this process. Additionally, campaigns aimed at training parents as psychosocial protective agents against adolescent aggressiveness, such as, for example media campaigns or family programs, should be informative (Cornelius, Earnshaw, Menino, Bogart, & Levy, 2017; Rinaldi & Farr, 2018). Specifically, interventions with aggressive adolescents and their parents should be focused on fostering a warmth relationship within the family, based on dialogue and affection, helping the aggressive adolescents to improve their family perceptions, as valued and appreciated members in home. So in the legal context, one possible reason about the infectivity of mandatory family therapies might be the poor self-image of adolescent offenders about their families (Garcia-Poole, Byrne, & Rodrigo, 2019; Martin, Padron, & Redondo, 2019). Nevertheless, this point should be tested in future studies with adolescent offenders and their families in juvenile programs.

Additionally, findings from the present study agree with previous studies on the relations between the demographic variables of sex and age and self-esteem and psychological maladjustment (Fuentes et al., 2015; García & Gracia, 2009; Martinez & Garcia, 2007, 2008). On self-esteem outcomes, females indicate better family self-esteem than males, but poorer physical and emotional self-esteem. Age-related differences indicate that the lowest family and physical self-esteem corresponded to adolescents from 16 to 17 years old. On emotional maladjustment, males reported greater negative self-adequacy and emotional instability than females, but lower emotional irresponsiveness. Age-related differences showed that adolescents from 12-15 years old reported greater negative self-esteem, emotional irresponsiveness, and emotional instability than their peers from 16-17 years of age.

This study has strengths and limitations. The two-dimensional, four-style theoretical framework allows parenting scholars to examine parenting socialization and its adjustment and competence correlates across different countries, settings, and sociodemographic characteristics, in order to make specific hypotheses about the best parenting style that scholars can test and replicate. It should be cautious about the cross-sectional design because it does not determine causality, although it links parenting in raising children, aggressiveness predisposition, and competence and adjustment in adolescents (Fariña, Redondo, Seijo, Novo, & Arce, 2017). The present findings should be considered preliminary because they are not based on longitudinal or experimental evidence. Finally, families were classified into one of four typologies (authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, or neglectful) based on adolescents’ rates instead of parents’ responses, although similar findings have been found in previous studies with parenting styles using different data collection methods (Lamborn et al., 1991; Steinberg et al., 1994).

In spite of these limitations, the present findings corroborate the problems related to aggressiveness among adolescents, pointing to the family as a protection or risk factor for developmental outcomes. Previous research highlights the need to examine whether optimal parenting transcends the boundaries of children’s individual characteristics, such as their aggressiveness predisposition. Contrary to some previous research that recommends strict and imposing parenting in order to help aggressive adolescents to do well on obedience and conformity to adult standards, only warm families provide protection even in adolescents with an aggressive predisposition. Interestingly, in aggressive adolescents, their family component of sense of self is only preserved when they are raised in indulgent and authoritative families, even reporting scores between those of non-aggressive adolescents from non warm families (authoritarian and neglectful).