Sexual violence is one of the most humiliating and devastating forms of male violence against women and produces severe physical and psychological consequences (Smith et al., 2017; World Health Organization [WHO, 2017]). Sexual violence can manifest itself in different ways, including acts considered by Spanish legislation as sexual abuse, sexual aggression, and rape (Ley Orgánica núm. 10, 1995). However, when this violence takes place within couple relationships, it is especially frequent the use of different tactics of sexual coercion in order to obtain sex from the other person (Edwards et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2017).

Of all the tactics that can be used, "physical sexual coercion" or "aggression" appears to be the most severe. This direct and invasive type of violence consists of the threat or use of physical force to obtain or attempt to obtain sex (Bagwell-Gray et al., 2015; Fernández-Fuertes et al., 2018). For its part, verbal sexual coercion is less severe than physical coercion, and includes both positive and negative verbal coercion without force. When "negative verbal sexual coercion" is used, the aggressor gets to have sex by using manipulative and psychological tactics such as verbal pressure, control, manipulation (eliciting feelings of guilt, obligation, or fear of losing the relationship), and extortion (Bagwell-Gray et al., 2015; Fernández-Fuertes et al., 2018; Raghavan et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2018). However, "positive verbal sexual coercion" or "coaxing" includes the use of more subtle tactics that reflect a positive emotional tone, which involves sweet-talking and the use of benign and seductive tactics that reflect love and closeness (Camilleri et al., 2009; Livingston et al., 2004).

Prevalence of sexual coercion varies across studies. For instance, the US national survey on sexual violence conducted in 2015 found that 16% of women had suffered sexual coercion at some point in their lifetime (Smith et al., 2018). Regarding Europe, Krahé et al. (2015) showed that 20.3% of women from 10 European countries suffered sexual coercion by a former or current partner. The starting point of the present study is to acknowledge the importance of taking into consideration not only the more explicit sexual tactics, such as the use of physical force, manipulation, or extortion, but also tactics that are more subtle, given that the latter have a high prevalence in intimate partner relationships. Generally, sexual coercion involving physical force affects between 11% and 37% of women, whereas verbal coercion affects more than two in four women (Abbey et al., 2004; Brown et al., 2009; Young & Furman, 2013).

Furthermore, it is important to highlight the immeasurable consequences of intimate partner sexual violence for affected women in terms of physical (sleep alterations, sexual dysfunction, etc.), psychological (anxiety, depression, etc.), and behavioural (substance abuse, eating disorders, etc.) problems (WHO, 2017). However, in spite of its relevance and the consequences that sexual violence generates for women, this form of sexual violence is understudied (Livingston et al., 2004). This could be due to the fact that these actions are less visible, and that their perception is ambiguous. Concretely, sexual coercion can occasionally be normalised, particularly in couple relationships that have a history of consensual sex and in which there is the belief that women must continue to accept sex in future encounters (Edwards, Gidycz, et al., 2001). It is also important to remember that sexual coercion does not make up a legally recognized category of offense, and that victims are usually perceived as having been persuaded under psychological pressure, which implies that they are partially responsible and have some control over the situation (McGregor, 2005). Thus, victims of a sexual coercion behaviour could be questioned when they do not fulfil traditional gender roles, even by police and legal operators who deal with these cases. All this can contribute to victims of sexual coercion normalising the situation and even failing to understand that they are victims of a crime, thus not reporting the experienced situation and maintaining their abusive relationship.

The present study offers the opportunity for an examination of the influence of the type of tactic of sexual coercion used by the aggressor on individuals' perception about perpetrator´s responsibility and probability of leaving the relationship.

Attribution of Responsibility and Leaving an Abusive Relationship

Once sexual violence has occurred within a couple relationship—and given its negative effects on the victims—, the victim can even question the decision to leave or remain in the relationship (Arriaga et al., 2013). At this point, the type of sexual tactic that the aggressor uses will have an impact on such a decision (Rhatigan et al., 2006).

Thus, for instance, people differ in their perception of the severity of the action depending on whether or not the tactic to obtain sex involves physical force (Capezza & Arriaga, 2008). In this sense, when sexual violence includes the use of verbal aggression is perceived less negatively than when sexual violence includes the use of physical aggression (Capezza & Arriaga, 2008; Hammock et al., 2015). Furthermore, the probability of continuing in an abusive relationship is higher for women who have suffered subtle forms of sexual coercion than for women with experiences of physical sexual coercion (Edwards, Kearns, et al., 2012).

Another variable that has an impact on taking the decision to leave a couple relationship which is also affected by the type of the tactic used is the attribution of responsibility for the action. The perception that victims are guiltier than aggressors justifies sexual violence, thus normalising the situation and denying the severity of the damage caused (Weiss, 2009), and decreasing the probability of leaving the relationship (Edwards et al., 2012). This justification is more likely to occur when sexual violence has been subtle, attributing more responsibility to the victim than the aggressor when sexual violence involves more subtle tactics than when it involves the use of physical force (Capezza & Arriaga, 2008; Katz et al., 2007). Research about sexual victimisation has found similar results, showing that victims of physical sexual coercion attribute more responsibility to an aggressor than victims of verbal sexual coercion (Brown et al., 2009; Byers & Glenn, 2012).

Dependence as a Risk Factor

When sexual violence occurs in a couple relationship, it is not only the type of the tactic used and the attribution of responsibility that determine whether the person will remain in the relationship; this decision could also be affected by relational factors that are considered to be a risk, such as dependence.

Dependence on a partner is an affective need of a member in the relationship towards the other member (Ruppel & Curran, 2012). It also involves thoughts, feelings, and behaviours that revolve around the need for interaction and the seek for approval from the partner (Valor-Segura, Expósito, & Moya, 2009). Dependent people request constant protection and support, considering their partner as the centre of their existence, idealising that person, and submitting to him/her (Tan et al., 2018). Therefore, dependent individuals feel compelled to preserve their relationship, being more tolerant towards their partner's abuse, serving dependence as a risk factor for maintaining abusive relationships (Tan et al., 2018; Valor-Segura, Expósito, Moya, & Kluwer, 2014).

Empirical evidence has demonstrated that individuals involved in an abusive relationship are more dependent than individuals involved in a non-abusive relationship (Tan et al., 2018). Based on this premise, when a person is living a conflicting situation, dependence can facilitate the dysfunctional internalisation of guilt, leading to reinterpreting the situation and attributing errors to oneself, and experiencing feelings of incompetence with respect to the relationship (Valor-Segura, Expósito, Moya, et al., 2014). This self-blaming, along with feelings of inferiority and a loss of control, lead the person to exonerating and forgiving the aggressor, thereby minimising the relevance of violent episodes (Enander, 2010; Hadeed & El-Bassel, 2006), which decreases the likelihood of leaving the relationship (Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003). Concretely, Valor-Segura, Expósito, Moya, et al. (2014) showed that dependence is related to stronger feelings of guilt and hence a higher reliance on passive strategies to solve conflicts. Similarly, Beltrán-Morillas et al. (2019) found that high levels of dependence are associated with greater forgiveness towards partner. Based on these results, this study suggests that dependence will have an indirect effect on the probability of leaving a relationship through attributed responsibility. Further, it is considered that the relationship between dependence and the decision of whether or not to leave the relationship will occur when more subtle tactics are used to enforce sexual violence, given that it is in these situations that relational factors play a major role in the decision making process (e.g., Garrido-Macías et al., 2017).

In summary, this study focuses on two main objectives, which are addressed in two studies. Study 1 aimed to select scenarios about different sexual tactics (sexual aggression, sexual coercion, and sexual coaxing) that obtain the highest content validity scores. Study 2 aimed to analyse the effect of the type of sexual tactic and dependence on both the attribution of responsibility and the probability of leaving a relationship. Thus, it is expected to find a higher responsibility attributed to the aggressor and a higher probability of leaving a relationship when sexual tactics are more severe (aggression vs. coercion vs. coaxing) (Hypothesis 1 and 2). Further, regarding dependence as a risk factor, it is expected to find that high dependence lead to a lower responsibility attributed to the aggressor and, hence, a lower probability of leaving a relationship, and that such a relationship occurs when the type of sexual tactics used are less severe (coaxing) (Hypothesis 3).

Study 1

This study focuses on establishing scenarios about different coercive sexual tactics and their subsequent qualitative evaluation using an expert judgement procedure (Sireci & Faulkner-Bond, 2014), in order to select those with the best evidence of content validity to use them in Study 2.

Method

Participants. The sample consisted of 5 experts who were familiar with constructs to be evaluated, 4 female (80%) and 1 male (20%).

Procedure and design. Selection of the experts was carried out following the recommendations by Skjong and Wentworht (2001). Thus experts who had experience in judgement and decision making were selected based on evidence or expertise, a good reputation in their areas and availability and motivation to participate. The expert panel consisted of 4 full professors and 1 assistant professor from the Clinical and Social Psychology Department who were specialising in gender violence, sexual violence, and health.

A specification table of the different scenarios was provided to the experts (Spaan, 2006), including the semantic definition of the three constructs to be evaluated (sexual coaxing, sexual coercion, and sexual aggression). Then, six scenarios designed to evaluate the constructs were presented to the expert. Experts' qualitative evaluation task consisted of judging each scenario based on the degree of belonging to each construct, as well as their level of representativeness, understanding, interpretation, and clarity (Martínez, 1995).

Instruments. A template was designed with the instructions that judges were required to follow, as well as the semantic definitions of target constructs. They were then presented the following measurements:

Scenarios: Six scenarios that had been previously used in other studies (e.g., Katz et al., 2007; Munsch & Willer, 2012; Tamborra et al., 2014) were employed (two for each type of tactic), with relevant adjustments to suit them to the desired conditions. These scenarios described an undesired sexual relation in a couple that had been dating for a while, with different tactics used by the male (sexual coaxing, sexual coercion, or sexual aggression) to get sex with the female.

Belonging: This evaluates the degree of belonging of each scenario to each of the three constructs; judges had to mark with an X the construct to which they thought each scenario belonged.

Representativeness: This evaluates the degree to which the scenario is judged as being representative of the construct. A Likert-type response scale was used with options ranging from 1 (not representative) to 4 (very representative).

Understanding: This evaluates whether the scenario is understandable. A Likert-type response scale was used with options ranging from 1 (unintelligible) to 4 (clearly understandable).

Interpretation: This evaluates whether the scenario can be interpreted in different ways. A Likert-type response structure was used with responses ranging from 1 (it can be interpreted in multiple ways) to 4 (it has only one interpretation).

Clarity: This evaluates the degree to which the scenario is concise, short, and direct. A Likert-type response format was used with options ranging from 1 (extensive, lack of concision) to 4 (concise, direct).

Results

In order to establish a criterion for selecting which scenario out of the six was better suited to each of the three constructs to be used in Study 2, recommendations from Ayre and Scally (2014) were followed, so that with a sample size of 5 experts 100% agreement is needed in determining that the scenario is necessary and appropriate in. When this criterion was not met, the scenario was checked again, analysing potential problems and proposing an alternative scenario that was better adjusted to the construct. Moreover, in order to be considered adequate, the scenarios had to obtain a minimum score of 3.2 (80% of maximum score) for the remainder dimensions evaluated (representativeness, understanding, interpretation, and clarity).

Table 1 represents the percentage of experts that correctly assigned each scenario to its construct, as well as the mean scores given for representativeness, understanding, interpretation, and clarity. The results show that all the scenarios were assigned correctly to their constructs, except scenario 5, which only had 80% of agreement by experts. Further, in order to ensure inter-judge agreement, kappa coefficient (Fleiss, 1971) was used, and an adequate agreement between them was obtained (k = .798). Regarding the remainder dimensions evaluated, all the scenarios obtained scores that were equal to or higher than 3.2. Subsequently, having gathered the mean scores for representativeness, understanding, interpretation, and clarity for each of the scenarios, it was decided that those with the highest scores in each construct will be chosen. Thus, scenario 3 for the coercion construct was selected (M = 3.70, SD = 0.47), scenario 4 for coaxing (M = 3.65, SD = 0.49), and scenario 6 for aggression (M = 3.95, SD = 0.22).

Study 2

The procedure for the selection of scenarios using the expert judgements in Study 1 provided the basis for the experimental manipulations to be used in Study 2. Thus, three conditions were used: sexual coaxing, sexual coercion, and sexual aggression.

Method

Participants. The sample consisted of 304 Spanish participants from the general population and was composed of 101 males (33.2%) and 203 females (66.8%), with an age range between 18 and 65 years (M = 27.6, SD = 9.42). Out of this sample, 92.1% was heterosexual, 6.6% was homosexual, and 1.3% was bisexual. Finally, 95 (31.3%) participants were single, whereas 209 (69.7%) participants had a partner.

Procedure and design. An incidental sampling method to select the participants was used. This sampling method was carried out in different areas (bus station, airport, etc.), which allowed us to obtain a broad range of participants. A research assistant approached people and asked them if they wanted to participate in a study about couple relationships. All participants were volunteers and completed the measures under the supervision of a research assistant in separate seats. They read a consent form assuring confidentiality and anonymity, thereby complying with the university research ethic committee. When they finished the task, they placed their completed questionnaires in envelopes so that everyone turned in identical blank envelopes. Before leaving, they were debriefed about the purpose of the study and given contact information from the researchers. All procedures were approved by the University of Granada Ethic Committee.

The study adopted a unifactorial multivariate design, with the type of tactic (coaxing, coercion, or aggression) as independent variable and the attribution of responsibility and probability of leaving the relationship as dependent variables. Furthermore, dependence towards partner was examined as measured predictor variable.

Measuring instruments. An instrument that included the target measures was designed. First, the description of a scenario in which a sexual violence situation occurred was presented to the participants, manipulating the type of tactic used by the aggressor (coaxing, coercion, or aggression). Participants were randomly allocated to one of the three conditions. Participants' task was reading the scenario and imagining that they were in that described sexual violence situation. Finally, participants answered to a series of questions related to the situation.

Perception of the severity of the tactic (manipulation check): The perception of the severity of the tactic was evaluated aimed at measuring participants' perception of a tactic's severity ("how severe do you consider the described situation to be?") described in the scenario. It has a Likert-type response structure ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much).

Attribution of responsibility: With the attribution of responsibility, responsibility attributed to the aggressor by participants was measured, creating a single score through the average of two items ("to what extent do you consider Antonio is responsible for what occurred?" and "to what extent do you think Ana is responsible for what occurred?"). A Likert-type scale was used ranging from 1 (not responsible/not severe) to 7 (very responsible/very severe), where higher scores reflected higher responsibility attributed to the aggressor. The correlation between both items is r = .12, p = .03.

Probability of leaving the relationship: One item evaluated the degree to which individuals would leave a relationship if the situation described in the scenario happened to them ("to what extent would you be willing to leave the relationship if the situation happened to you?"). A Likert-type scale was used ranging from 1 (I would not leave the relationship) to 7 (I would definitely leave the relationship).

Spouse-Specific Dependence Scale (SSDS; Valor-Segura, Expósito, & Moya, 2009). This scale consisted of 17 items evaluating the degree of dependence on the partner (e.g., "without my partner, the demands of life would seem like too much to handle"). The general scale includes three dimensions: emotional dependence, exclusive dependence, and anxious attachment, and for this study the global score of the scale was used. A Likert-type scale was used ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 6 (totally agree). This scale has been previously used and validated with Spanish population (Valor-Segura, Expósito, & Moya, 2009), and the alpha coefficient obtained for total dependence in this sample was .83. To answer this scale, participants who are involved in a relationship had to think in their current partner, whereas single participants had to answer thinking of their last relationship.

Social-demographic characteristics: Data relating to gender, age, civil status, and time in a relationship were obtained.

Results

Manipulation check. In order to check that the experimental manipulation was correct, an ANOVA was conducted, using the type of tactic as the independent variable (coaxing, coercion, and aggression) and the perception of severity as the dependent variable. The results revealed an effect of the type of tactic on the perceived severity, F(2, 301) = 50.88, p < .001, η2p = .25. It was found differences between the three conditions when post hoc tests were carried out. Thus, a significant higher severity is perceived by those participants in the aggression condition (M = 6.53, SD = 0.90) in comparison with those in the coercion condition (M = 5.63, SD = 1.44; Hedges' g = 0.75). Furthermore, higher perceived severity was found for participants in the coercion condition relative to the coaxing condition (M = 4.55, SD = 1.74; Hedges' g = 0.76) (Table 2).

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations between the Study Variables Depending on the Type of Tactic

Note. Coa = coaxing; Coe = coercion; Agg = aggression; De = dependence; AR = attributed responsibility; PL = probability of leaving the relationship.

* p < .05.

** p < .01.

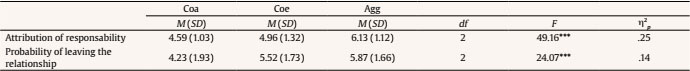

Effect of the type of tactic on the attribution of responsibility and the probability of leaving the relationship. To test Hypotheses 1 and 2, which expected to find that individuals attributed more responsibility to the aggressor and were more likely to leave the relationship when the tactic used was more severe, a MANOVA analysis was carried out, with the type of tactic as independent variable (coaxing, coercion, or aggression), and attributed responsibility and probability of leaving the relationship as dependent variables.

First, the analyses revealed an effect of tactic on the attribution of responsibility, Wilk's λ = .69, F(2, 301) = 49.16, p < .001, η2p = .25, that is, post hoc tests showed differences between the coaxing and aggression conditions (4.59 vs. 6.13, for the coaxing and aggression condition, respectively; Hedges' g= 1.43), and also between coercion and aggression (4.96 vs. 6.13 for the coercion and aggression condition, respectively; Hedges' g = 0.95). Thus, the aggressor was attributed more responsibility when the type of tactic used was aggression compared with the case in which the aggressor used coaxing or coercion (see Table 3).

Table 3. Mean Scores and Standard Deviations in Justifying the Aggression Depending on the Type of Tactic

Note. Coa = coaxing; Coe = coercion; Agg = aggression

*** p < .001

Second, the results indicated an effect of the type of tactic on the probability of leaving the relationship, Wilk's λ = .69, F(2, 301) = 24.07, p < .001, η2p =.14, that t is, a post hoc analysis found differences between coaxing and coercion (4.23 vs. 5.52, for the coaxing and coercion condition, respectively; Hedges' g = 0.70), and between coaxing and aggression (4.23 vs. 5.87 for the coaxing and aggression condition, respectively; Hedges' g = 0.91). Thus, it was found that there was a higher probability of leaving the relationship when the tactics used were aggression or coercion compared with the case in which coaxing was used (see Table 3).

The mediating effect of attribution of responsibility in the relationship between dependence and the probability of leaving the relationship moderated by the type of tactic. Hypothesis 3 predicted a negative relationship between dependence and the probability of leaving the relationship; this hypothesis also anticipated that this relationship would be mediated by the attribution of responsibility and moderated by the type of tactic (coaxing, coercion, or aggression). In order to test this, model 5 of the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2013) was used. This model allowed testing the indirect effect of dependence on the probability of leaving a relationship through the attribution of responsibility, as well as the direct effect of dependence on the probability of leaving a relationship, conditioned by the type of tactic used (see Figure 1). A bootstrapping non-parametric procedure with 5000 repetitions was used in order to estimate confidence intervals of 95%. Table 4 shows the results, which indicate an effect of dependence on the attribution of responsibility (β = -.22, p = .058, CI [-.45, -.01]), and an effect of the attribution of responsibility on the probability of leaving the relationship (β = .28, p = .007, CI [.08, .48]). A significant indirect relationship between dependence and probability of leaving the relationship through the attribution of responsibility [CI = -.17, -.01] was found. Further, it was observed an interaction effect between dependence and the type of tactic on the probability of leaving the relationship (β = .33, p = .045, CI [.01, .66]), being verified at the bottom of Table 4 that this effect only occurs when the type of tactic used is coaxing (β = -.41, p = .045, CI [-.81, -.01]).

Figure 1. Mediation of Attribution of Responsibility in the Relationship between Dependence and the Probability of Leaving the Relationship through the Type of Tactic.

Table 4. Results of Regression Analyses for Moderate Mediation (Model 5)

Note. The coefficients of regression (non-standardised) are presented in. Bootstrap size = 5000. The indirect effect is significant where the confidence intervals lack value 0. LLCI = lower level 95% of the confidence interval in bootstrap percentile; SE = standard error; ULCI = upper level 95% of the confidence interval in bootstrap percentile

Discussion

The focus of the present work was to explore whether the type of tactic of sexual coercion used to practise intimate partner sexual violence could have an impact on the responsibility attributed to the aggressor and the decision to leave the relationship. In addition, Analysing the role of dependence on the decision making process was sought.

The first primary aim was to select the scenarios that best represent the three types of sexual coercion tactics described in the literature (sexual coaxing, sexual coercion, and sexual aggression). Through an expert judgment, Study 1 allowed to identify the mentioned scenarios, thus providing evidence of their content validity so that they could be employed correctly in Study 2.

Regarding Study 2, we expected that when a perpetrator resorts to more severe tactics (sexual aggression vs. sexual coercion vs. sexual coaxing) to try to get sex from his partner, individuals will attribute him more responsibility and will be more likely to leave the relationship than if he relies on less severe tactics. This is precisely what we found, extending previous findings (e.g., Brown et al., 2009; Byers & Glenn, 2012; Edwards et al., 2012; Katz et al., 2007) in demonstrating that individuals tend to leave a relationship and attribute more responsibility to the aggressor when the tactics used to perform intimate partner sexual violence have been stronger or more explicit (physical aggression) in comparison with the case where more subtle tactics have been used (verbal coercion or coaxing).

These findings therefore support the Hypotheses 1 and 2. Thus, as suggested in previous studies, individuals are more likely to tolerate this type of transgression when the tactic used is subtle (Hammock et al., 2015), hence attributing more responsibility to the victim, less responsibility to the aggressor, and perceiving the action as less severe (Capezza & Arriaga, 2008; Katz et al., 2007), thus decreasing the probability of leaving the abusive relationship (Edwards et al., 2012).

he current research also examined whether dependence would predict individuals’ perceptions of the sexual coercion situation, acting as a risk factor in the decision to remain in an abusive relationship. The results appear to confirm the Hypothesis 3, showing an indirect effect of dependence on the probability of leaving the relationship through attributed responsibility, that is, individuals with high levels of dependence tend to place less blame on the aggressor (Enander, 2010; Hadeed & El-Bassel, 2006), which implies a lower probability of leaving the abusive relationship (Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003). This could shed some light on the reasons why victims of sexual violence often report violence to a lesser extent when it occurs within their intimate relationship, since dependence towards their partner contributes to a lower responsibility to the aggressor and a lower probability of leaving the relationship. Finally, results showed that the influence of dependence on the maintenance of an abusive relationship occurs only when the type of tactic used is less severe (positive verbal sexual coercion or coaxing). Thus, it seems clear that the risk factors have greater impact when deciding whether to maintain or leave an abusive relationship when the man adopts subtle tactics of sexual violence in order to have sex (e.g., Garrido-Macías et al., 2017).

Although this research provides relevant contributions to understanding how sexual coercion is perceived, several limitations should be noted. Regarding hypothetical scenarios, although they have been used extensively because of their usefulness to vary specific features while holding other features constant (e.g., Hammock et al., 2015; Katz et al., 2007; Tamborra et al., 2014) and afforded this advantage in making sexual claims, participants’ responses in these situations could differ from real-life responses. Furthermore, previous experience of sexual violence and general attitudes towards violence against women (e.g., rape myths, sexist ideology) should be considered in future studies, since past research has found these attitudes are crucial for understanding reactions and behaviours towards victims and aggressors (e.g., Herrera et al., 2014, 2018). An additional limitation is that participants were from the general population, so that caution should be taken when generalising the results for professional or applied practice. In this sense, results found here might be stronger with a clinical sample of victims of intimate partner sexual violence, assessing experiences rather than attributions based on fictional scenarios.

Conclusions

Sexual coercion is one of the most frequently forms of sexual violence within romantic relationships (e.g., Krahé et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2017) and is usually normalised and minimised in this context (e.g., Edwards et al., 2011; Guggisberg, 2017; WHO, 2017), especially when it occurs in its more subtle forms, without the use of physical force. In this sense, this research allow us to explore how, depending on the type of tactic used by the aggressor (more or less serious), the aggressor is considered more or less guilty and it is more or less likely that individuals decide to leave the relationship.

The results of this study have relevant theoretical and practical implications by analysing different forms of verbal sexual coercion that are more subtle and less recognised as sexual violence, facilitating the identification by women themselves of kinds of experiences of sexual coercion that go beyond the common definition of such sexual coercion. This identification could contribute to increasing the visibility of sexual coercion as an unacceptable act of sexual violence that should be considered in the criminal code as a crime against women’s sexual freedom. In this way, victims, firstly, would perceive greater legal support that would increase the likelihood of such women denounce these situations of intimate partner sexual coercion and leaving the abusive relationship. Secondly, general population, police and legal operators could increase their awareness about situations that are liable to be rejected and denounced, favouring a greater perception of credibility of the victims and less attribution of responsibility to them.