Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.101 no.5 Madrid may. 2009

Morgagni-Larrey parasternal diaphragmatic hernia in the adult

Hernia diafragmática paraesternal de Morgagni-Larrey en adulto

L. A. Arráez-Aybar1,2, C. C. González-Gómez2 and A. J. Torres-García3

1Department of Anatomy and Human Embryology II. School of Medicine. Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

2Instituto de Ciencias Morfofuncionales.

3Department of General Surgery and Digestive Diseases II. Hospital Clínico Universitario de San Carlos. UCM. Madrid, Spain

ABSTRACT

With a prevalence of 0.3-0.5/1000 births, congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) remains a serious, poorly understood abnormality with a high mortality rate that cannot always be effectively managed. Its reported frequency in Spain is 0.69%oo with a yearly decreasing trend of 0.10%oo during the period 1980-2006. Up to 5% of cases are incidentally identified in adults undergoing studies for other reasons.

We report the case of a 74-year-old woman with vomiting for three months due to parasternal diaphragmatic hernia of Morgagni-Larrey (retrochondrosternal, retrocostoxyphoid, retrosternal, subcostal, substernal or subcostosternal hernia), which allowed us to report an update on this condition in the adult, and on thoracoabdominal diaphragm morphogenesis. It is in the embryology of the diaphragm where an explanation may be found for some morphological changes and clinical manifestations, even though a number of uncertainties remain. We also analyze the extent of controversy persisting on some aspects of surgical treatment (access routes, mesh use, hernial sac reduction). Overall, minimally invasive techniques predominate. We consider laparoscopy the approach of choice for adult patients with parasternal hernia eligible for surgery.

Key words: Diaphragmatic hernia. Diaphragm. Laparoscopy. Embryology. Anatomy.

RESUMEN

Con una prevalencia de 0,3-0,5/1.000 nacimientos, la hernia diafragmática congénita (HDC) sigue siendo una anomalía grave, no bien entendida, alta mortalidad y tratamiento no siempre efectivo. En España se ha informado de una frecuencia del 0,69%oo con una tendencia decreciente en el periodo 1980-2006 del 0,10%oo por año. No obstante, hasta un 5% se diagnostican en adultos durante la realización de un reconocimiento por otra causa.

Presentamos un cuadro de vómitos de tres meses de evolución en una mujer de 74 años por hernia diafragmática paraesternal de Morgagni-Larrey (retrocondroesternal, retrocostoxifoidea, retroesternal, subcostal, subesternal o subcostoesternal), que nos ha permitido realizar una actualización de esta patología en adultos y de la morfogénesis del diafragma toracoabdominal. Es en la embriología del diafragma donde encontramos explicación de algunas de sus alteraciones morfológicas y características clínicas, si bien persisten aspectos confusos de la misma. También analizamos el grado de controversia que persiste en algunos aspectos de su tratamiento quirúrgico (vías de acceso, uso o no de mallas y reducción o no del saco herniario). Por lo general priman las técnicas mínimamente invasivas. Consideramos el abordaje laparoscópico como de elección en pacientes adultos con hernia paraesternal candidatos a la cirugía.

Palabras clave: Hernia diafragmática. Diafragma. Laparoscopia. Embriología. Anatomía.

Introduction

A weak area in a portion of the diaphragm or diaphragmatic hernia (DH) may allow abdominal contents to enter the thorax. A diaphragmatic hernia may be located in the esophageal hiatus (hiatal hernia), in its proximity (paraesophageal hernia), at a posterolateral level -Bochdalek's hernia (BH)-, or at a parasternal level -parasternal (PDH), retrochondrosternal, retrocostoxyphoid, retrosternal, subcostal, substernal, or subcostosternal hernia-.

Etiologically, hernias may be acquired or congenital. Up to 7% of patients suffering from closed thoracoabdominal trauma have a post-traumatic diaphragmatic tear, most often on the left side (1). Increased intra-abdominal pressure and thoracic depression may be significant factors for the development of later hernias (in the adult or the elderly) (2). Thus, in obese patients or subjects with kyphoscoliotic deviation, repeat high abdominal pressure events, as in vomiting or coughing (acquired substrate), may affect reduced-resistance areas in the diaphragm (congenital substrate) (3).

A congenital origin may be demonstrated when symptoms develop in the newborn, but cases have been reported outside the neonatal period. The prevalence of congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is 0.3-0.5/1,000 births, and hernias are more often located on the left side and predominate in women (2:1) (4). A frequency of 0.69%oo has been reported in Spain, with an annual decreasing trend of 0.10%oo for the period 1980-2006 (5). BH has a prevalence of 1/2,200 births, and PDH has a prevalence of 1/1 million births (6).

In practice CDH is a serious, poorly understood abnormality with a high mortality rate -resulting from underlying pulmonary hypoplasia- whose management is not always effective (7). Most of these hernias are found and repaired in children, but 5% are incidentally diagnosed in adults studied for other conditions (8).

A potential hereditary connection was reported in two instances - a patient who had a mother with PDH and a daughter with congenital pulmonary hernia (9), and a case of CDH in twins (10). Around 10% of all individuals with CDH have chromosomal abnormalities (11). Table I lists some of these syndromes.

Since the studies by Bremer (12) and Wells (13), a widely accepted theory is that CDH stems from diaphragmatic dysgenesis; however, the embryology of the diaphragm remains obscure to this very day.

Diaphragm morphogenesis

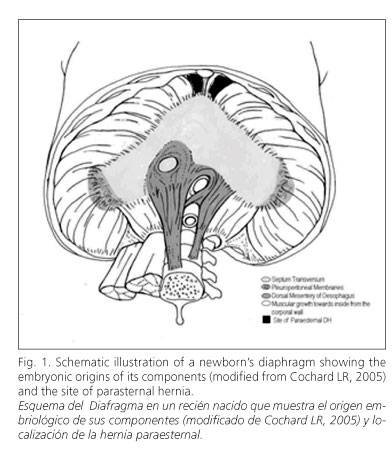

It takes place between the 4th and 12th weeks of gestation. It is a complex process that starts in the cervical region and proceeds in a caudal direction. Table II and figures 1 and 2 schematically illustrate diaphragm development. The diaphragm is made up from four embryonic structures (14-18): 1) Septum transversum (ST) of His or transverse mass of Uskow: a mesodermal bridge representing the primordium of the diaphragm's phrenic center. It grows dorsally from the body's ventrolateral wall. 2) Pleuroperitoneal membranes (PPMs) or pleuroperitonal laminae of Brachet or pillars of Uskow: folds developing on each side of the coelom's dorsal wall. They grow ventrally and progress closely paralleling regional veins. The costovertebral trigone does not represent the closing of PPMs (19). 3) Dorsal esophageal mesentery (DEM): represents the muscle bundles of the diaphragmatic crura. PPMs converge on DEM and fuse with ST's dorsal portion (primordial diaphragm). The right hemidiaphragm consolidates earlier than the left one; this, together with the liver's position on the right side, would explain why BH is more common here; regarding PDH, its higher frequency on the right side would result from the pericardium protecting the left flank, which would hinder its development in this area. 4) Muscle grows medially from the body's wall: from week 9 to week 12 (fetal period), as lungs increase in size, pulmonary caudal apices open up additional spaces on the body's wall. The latter's associated mesenchyma, separated from the wall proper, constitutes a thin ring of tissue along the dorsolateral borders. The diaphragm's muscular component is made up by myotomes invading the mesenchyma following a dorsal-to-ventral direction, and the anterior diaphragm is formed last. Myoblasts derive from the third, fourth, and fifth cervical somites, with innervation also stemming from these segments. This is the common origin of both anterior diaphragmatic muscle fibers and the suprapleural membrane (Sibson's fascia) (9). The circumferential portions of the diaphragm are sensitively supplied from caudal intercostal nerves.

Concurrently with the caudal migration of the diaphragm, the sternum fuses together in a craneocaudal direction, and abdominal contents increase rapidly.

CDH pathogenesis

Several theories have been put forward since pre-hernial lipoma, which is always present in early stages, was condsidered to penetrate the sternocostal trigon dragging the peritoneum along (20).

No environmental pathogenetic factors have been reported for humans. CDH (always BH) has been experimentally induced with thalidomide (21), vitamin A deficiency (22), polybromobifphenyls (23) or nitrophen (24).

Attributions to the primary role of the lung, phrenic nerve, myotube formation, and pleuroperitoneal channel closure are currently considered false (25). Appropriate primordial diaphragm development has been shown not to depend on lung tissue signals, and diaphragm malformation has been seen to be a primary defect in CDH, resulting from a malformated, non-muscular mesenchymal diaphragm component prior to myogenesis (26).

In practice (18), when a dysontogenetic cause occurs during the embryonic phase (false hernia) the membranous diaphragm completion process comes to a halt, which conditions a persistent gap. Abdominal viscera will not be covered by peritoneum. Hernial sacs will lack peritoneal evaginations, as in BH. In contrast, when such a cause occurs during the fetal period (true hernia), with a closed pleuroperitoneal hiatus but incomplete muscle migration, the defect takes place in the muscular diaphragm. In such cases an increase in abdominal pressure may push abdominal viscera into the thoracic cavity. The hernial sac will have a peritoneal evagination, as in PDH. Exceptionally, as a result of lacunar diaphragmatic aplasia and persistent pericardio-peritoneal shunt, hernias may have no sac, which constitutes the extremely rare diaphragmatic peritoneal-pericardial hernia (27).

Case report

CDH is clinically asymptomatic in the adult in 30 to 50% of cases, and mainly affects overweight women (28). However, it may also present in thin individuals, as in the following case report.

A 74-year-old woman was admitted for intermittent food vomiting within 30 minutes and 24 hours after ingestion, and weight loss (10 kg) for the last three months. She had no history of abdominal trauma.

Physical examination only reveals a mildly reduced respiratory noise in the right hemithorax. There is dysphonia without odynophagia, and dysmotility-type dyspeptic manifestations.

Chest x-rays (Fig. 3) revealed the right pulmonary area to be occupied by a smoothly opaque, well-delimited, paracardial, antero-inferior mediastinal mass with air-fluid levels on the PA view, suggestive of intestinal loops.

MRI (Fig. 4) showed a parasternal mass and a wide defect in the anterior diaphragm, through which a hernial sac containing most of the gastric body and antrum, omentum, and right colon, consistent with PDH, ascends into the antero-lateral thorax.

The patient was operated upon using laparoscopic surgery under general anesthesia. A hernial hiatus 5 x 10 cm in size was found - hernial contents reduction and hernial sac resection were performed. The defect was closed using a polypropylene and silicone mesh from the abdominal side, which was anchored with suture stitches. The outcome was satisfactory.

Discussion

PDH is a hernia through the sternocostal triangle (trigonum sternocostale), the space across which superior epigastric vessels and lymph vessels from the liver's diaphragmatic aspect travel. A multifactorial etiology is currently posited that includes hereditary factors associated with other malformation syndromes (Table II). However, when PDH is diagnosed in children and adults, it is only rarely accompanied by other congenital malformations (29).

PDH represents 3-5% of all DHs (30). It was first described in 1761 by Giovanni Battista Morgagni (1682-1771) on the right sternocostal triangle an Italian stonecutter at necropsy. In 1829 Dominique J. Larrey (1766-1842), Napoleon's surgeon, described the retrosternal space as an access route for the management of pericardial tamponade. Some authors have designated the right sternocostal triangle "hiatus of Morgagni", and the left sternocostal triangle "hiatus of Larrey". Most authors consider the term "anterior diaphragmatic hernia of Morgagni-Larrey" to be the most adequate name (31). However, between the two muscular bundles of the diaphragm there is a tiny intersternal slit designated hiatus of Marfan, after the French pediatrician Antonin Marfan (1858-1942) (32). Should there be agenesis in either sternal bundle - right or left - the hiatus of Marfan may favor the hernial orifice and render its topography more challenging to recognize, hence we consider the term "parasternal diaphragmatic hernia of Morgagni-Larrey" more appropriate.

Clinically, most patients (72%) present with hernia-related symptoms, and pulmonary manifestations are most common (36%) (33). PDH is usually diagnosed with x-rays (chest PA and lateral views). Waelli was first to diagnose the condition in 1911 (34).

It must be differentiated from other masses in the anterior mediastinum (35). Pericardial diverticulum and cyst contain fluid, and are clearly related to the heart. Pericardial hematoma usually shows hyperdensity, is uncommon, and is usually associated with a history of chest trauma. In PDH, air contained in the mass - resulting from the passage of intestinal loops into the thorax - facilitates identification, which is difficult when only omentum is present. Differential diagnosis with lipoma is considered for fatty contents, which are perfectly distinguishable with CT.

CT is the primary diagnostic method, but may be inconclusive should the hernial sac be empty at imaging. Cases diagnosed with MRI and US have also been reported. MRI is a useful method to assess PDH - no radiation exposure, movement arctifact reduction, and potential multiplanar reconstruction (36). Ultrasonography may facilitate detection for PDH near the heart (37). PDH preferentially develops on the right side in 70% (38) to 91% (33) of cases.

Management

Given the low prevalence of this condition no conclusive treatment-related studies or guidelines are available. We consider surgery the therapy of choice even for asymptomatic patients in view of potential complications. Therapy selection will depend on individual patient characteristics, presence or absence of manifestations, and hernia location and size.

Some controversy remains regarding a few aspects of surgical treatment for PDH, including access routes (thoracic vs. abdominal), hernial sac reduction, and use of mesh.

During the 1950s (39) PDH was the one condition where an abdominal approach was favored; thoracic access was only required in the presence of hernial sac to sac contents adhesions. An abdominal approach is currently recommended for children (40), and is a requirement for complications such as hernial strangulation, incarceration (41) or perforation (42) regardless of patient age.

Thoracotomy has remained the most commonly used and/or reported access to this day because of benefits in terms of intraoperative diagnosis (33), greater exposure, easier repair (43), and mediastinal mass characterization (44).

An abdominal route will facilitate hernial reduction, and an identification of associated lesions at both the diaphragmatic level and anywhere else in the abdominal cavity at the expense of more postoperative complications and longer hospital stays. On the other hand, a thoracic route will facilitate hernial sac, pleural, and mediastinal dissection.

Authors perform hernia reduction in 100% of thoracotomies and 82% of laparotomies reported (33), but its benefits have not been demonstrated (45). In children, peritoneal sac dissection has resulted in some fatal pneumopericardium events. Other authors recommend excision only for small sacs with no intrathoracic adhesions, as the potential for injury to thoracic structures would be small. However, some believe that sac resection is a safe procedure and adhere to traditional surgical principles. This opinion may explain why thoracotomy has been the most commonly used surgical approach (42). In cases where the sac was not withdrawn some spontaneous reductions were seen, while others persisted with a fluid content. To prevent cyst formation some authors leave a drainage tube in the hernial sac. We consider that sac resection should not be attempted universally but selected on an individual basis.

On the other hand, most case reports do not consider using a mesh, which is usually of non-resorbable material when used (46).

However, since the first laparoscopic approach was reported in 1992 (47), surgeons have been using this technique increasingly. Benefits include ease of use, excellent access to the parasternal area (48), outstanding surgical field allowing appropriate manipulation with minimal trauma and complications (around 5%), and mean hospital stay of 3 days. Most of those who use this technique use mesh for defect repair (64%) and do not resect hernial sacs (69%) (42).

We consider laparoscopy the procedure of choice for adult patients with PDH who are eligible for surgery, and believe that surgeons should become familiar with this technique.

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

L.A. Arráez-Aybar.

Departamento de Anatomía y Embriología Humana II.

Facultad de Medicina. Universidad Complutense.

28040 Madrid, Spain.

e-mail: arraezla@med.ucm.es

Received: 02-12-08.

Accepted: 09-12-08.

References

1. Rodríguez-Morales G, Rodríguez A, Shatney CH. Acute rupture of the diaphragm in blunt trauma: analysis of 60 patients. J Trauma 1986; 26: 438-44. [ Links ]

2. De Medici A, Cebrelli CF, Cebrelli C, Cabano F, Zucchermaglio MT. A rare cause of intestinal occlusion: Morgagni-Larrey hernia. Chir Ital 1992; 44: 69-79. [ Links ]

3. Comer TP, Clagett OT. Surgical treatment of hernia of the foramen of Morgagni. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1966; 52: 461-8. [ Links ]

4. Feldman M. Sleisenger and Fortran's gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 6ª ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1998. [ Links ]

5. Bermejo E, Cuevas L, Mendioroz J, Martínez-Frias ML, Grupo Periférico del ECEMC. Surveillance of congenital anomalies in Spain: analysis of the ECEMC's data during the period 1980-2006. Bol ECEMC Rev Dismor Epidemiol 2007; 5: 54-80. [ Links ]

6. Taskin M, Zengin K, Unal E, Eren D, Korman U. Laparoscopic repair of congenital diaphragmatic hernias. Surg Endosc 2002; 16: 869. [ Links ]

7. Skari H, Bjornland K, Haugen G, Egeland T, Emblem R. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a meta-analysis of mortality factors. J Pediatr Surg 2000; 35: 1187-97. [ Links ]

8. Richardson WS, Bolton JS. Laparoscopic repair of congenital diaphragmatic hernias. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2002; 12: 277-80. [ Links ]

9. Catalona WJ, Crowder WL, Chretien PB. Occurrence of hernia of Morgagni with filial cervical lung hernia: a hereditary defect of the cervical mesenchyme? Chest 1972; 62: 340-2. [ Links ]

10. Tazuke Y, Kawahara H, Soh H, Yoneda A, Yagi M, Imura K, et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia in identical twins. Pediatr Surg Int 2000; 16:512-4. [ Links ]

11. Pober BR. Overview of epidemiology, genetics, birth defects, and chromosome abnormalities associated with CDH. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2007; 145C(2): 158-71. [ Links ]

12. Bremer JL. The diaphragm and diaphragmatic hernia. Archs Path 1943; 36: 539-49. [ Links ]

13. Wells LJ. Development of the human diaphragm and pleural sacs. Carnegie Contr Embryol 1954; 35: 107-34. [ Links ]

14. Carlson BM. Human Embriology and Developmental Biology. 2ª ed. Madrid: Harcourt; 2000. [ Links ]

15. Moore KL, Persaud TVN. The developing human (Clinically oriented embryology). 7ª ed. Madrid: Elsevier España; 2004. [ Links ]

16. Cochard LR (2005) Netter. Atlas de embriología humana. Barcelona: Masson SA; 2005. [ Links ]

17. Malas MA, Evcil EH. Size and location of the fetal diaphragma during the fetal period in human fetuses. Surg Radiol Anat 2007; 29: 155-64. [ Links ]

18. Orts-Llorca F. Anatomía Humana. 6a ed. Barcelona: Editorial Científico-Médica; 1986. [ Links ]

19. O´Rahilly R, Müller F. Human Embryology and Teratology. 2a ed. New York: Wiley-Liss Inc; 1996. [ Links ]

20. Thevenet A. Larrey's fissure anatomy of the hernial orifice in Morgagni hernias. Montp Med 1954; 46: 185-91. [ Links ]

21. Drobeck HP, Coulston F, Cornelius D. Effects of thalidomide on fetal development in rabbits and on establishment of pregnancy in monkeys. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1965; 7: 165-78. [ Links ]

22. Andersen DH. Effect of diet during pregnancy upon the incidence of congenital hereditary diaphragmatic hernia in the rat. J Path 1949; 25: 163-85. [ Links ]

23. Beaudoin AR. Teratogenicity of polybrominated biphenyls in rat. Environ Rev 1977; 14: 81-6. [ Links ]

24. Iritani I. Experimental study on embryogenesis of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Anat Embryol 1984; 169: 133-9. [ Links ]

25. Allan DW, Greer JJ. Pathogenesis of nitrofen-induced congenital diaphragmatic hernia in fetal rats. J Appl Physiol 1997; 83: 338-47. [ Links ]

26. Babiuk RP, Greer JJ. Diaphragm defects occur in a CDH hernia model independently of myogenesis and lung formation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2002; 283: 1310-4. [ Links ]

27. Kessler R, Pett S, Wernly J. Peritoneopericardial diaphragmatic hernia discovered at coronary bypass operation. Ann Thorac Surg 1991; 52: 562-3. [ Links ]

28. Fraser RS, Müller NL, Colman N, Paré PD. Fraser-Paré Diagnóstico de las Enfermedades del Tórax. 4ª ed. Madrid: Editorial Médica Panamericana; 2002. [ Links ]

29. Márquez Fernández J, Acosta Gordillo L, Carrasco Azcona MA, Medina Gil MC, Andrés Martín A. Hernia diafragmática de Morgagni de presentación tardía. An Pediatr (Barc) 2005; 62: 76-84. [ Links ]

30. Snyder WH, Greany EM. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: 77 consecutive cases. Surgery 1965; 57: 576-88. [ Links ]

31. Arzillo G, Aiello D, Priano G, Roggero F, Buluggiu G. Morgagni-Larrey diaphragmatic hernia. Personal case series. Minerva Chir 1994; 49: 1145-51. [ Links ]

32. García-Porrero JA, Hurlé JM. Anatomía Humana. Madrid: Mc Graw Hill-Interamericana; 2005. [ Links ]

33. Horton JD, Hofmann LJ, Hetz SP. Presentation and management of Morgagni hernias in adults: a review of 298 cases. Surg Endosc 2008; 22: 1413-20. [ Links ]

34. Hajdu NH, Sidhva JN Parasternal diaphragmatic hernia through the foramen of Morgagni; with report of a case. Br J Radiol 1955; 28:355-7. [ Links ]

35. Pedrosa CS, Cabeza Martínez B. El mediastino. Lesiones del mediastino anterior. En: Pedrosa CS, editor. Diagnóstico por imagen. 2a ed. Madrid: Mc Graw-Hill Interamericana; 1997. [ Links ]

36. Collie DA, Turnbull CM, Shaw TR, Price WH. Case report: MRI appearances of left-sided Morgagni hernia containing liver. Br J Radiol 1996; 69: 278-80. [ Links ]

37. Sajeev CG, Francis J, Roy TN, Fassaludeen M, Venugopal K. Morgagni hernia in adult presenting as cardiomegaly. J Assoc Physicians India 2003; 51: 85-6. [ Links ]

38. Rodríguez Hermosa JI, Tuca Rodríguez F, Ruiz Feliu B, Gironès Vilà J, Roig García J, Codina Cazador A, et al. Diaphragmatic hernia of Morgagni-Larrey in adults: analysis of 10 cases. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003; 26: 535-40. [ Links ]

39. Sweet RH. Diaphragmatic hernia. In: Sweet RH, editor. Thoracic Surgery. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1950. [ Links ]

40. Sönmez K, Karabulut R, Türkyilmaz Z, Demiro?ullari B, Ozen O, Af?arlar C, et al. Treatment of Morgagni hernias by transabdominal approach. West Indian Med J 2006; 55: 319-22. [ Links ]

41. Alvite Canosa M, Alonso Fernández L, Seoane Vigo M, Berdeal Díaz M, Pérez Grobas J, Carral Freire M, et al. Hernia de Morgagni incarcerada en un adulto. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2008; 100: 438-45. [ Links ]

42. Yilmaz M, Isik B, Coban S, Sogutlu G, Ara C, Kirimlioglu V, et al. Transabdominal approach in the surgical management of Morgagni hernia. Surg Today 2007; 37: 9-13. [ Links ]

43. Kiliç D, Nadir A, Döner E, Kavukçu S, Akal M, Ozdemir N, et al. Transthoracic approach in surgical management of Morgagni hernia. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2001; 20: 1016-9. [ Links ]

44. Minneci PC, Deans KJ, Kim P, Mathisen DJ. Foramen of Morgagni hernia: changes in diagnosis and treatment. Ann Thorac Surg 2004; 77: 1956-9. [ Links ]

45. Akbiyik F, Tiryaki TH, Senel E, Mambet E, Livanelio?lu Z, Atayurt H. Is hernial sac removal necessary? Retrospective evaluation of eight patients with Morgagni hernia in 5 years Pediatr Surg Int 2006; 22: 825-7. [ Links ]

46. Holcomb GW 3rd, Ostlie DJ, Miller KA. Laparoscopic patch repair of diaphragmatic hernias with Surgisis. J Pediatr Surg 2005; 40: E1-5. [ Links ]

47. Kuster GGR, Kline LE, Garzo G. Diaphragmatic hernia through the foramen of Morgagni : laparoscopic repair case report. J Laparosc Endosc Surg 1992; 2: 93-100. [ Links ]

48. Pérez Lara FJ, Lobato Bancalero LA, Moreno Ruiz J, de Luna Díaz R, Hernández Carmona J, Doblas Fernández J, et al. Hernia de Morgagni asociada a hernia de hiato. Reparación de la vía laparoscópica. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2006; 98: 789-98. [ Links ]

texto en

texto en