Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Archivos Españoles de Urología (Ed. impresa)

versión impresa ISSN 0004-0614

Arch. Esp. Urol. vol.60 no.4 may. 2007

Vattikuti Institute Prostatectomy (VIP) and current results.

Mahendra Bhandari and Mani Menon.

Vattikuti Urology Institute. Henry Ford Health System. Detroit. USA.

SUMMARY

Objectives: To describe a technique of Robot Assisted Radical Prostatectomy (RAP) for localized carcinoma of the prostate, the Vattikuti Institute Prostatectomy (VIP) and an innovative incremental nerve preservation technique, the Veil of Aphrodite. We also report complications, oncolgical and functional outcomes in a cohort of the patient operated during 2001-2006.

Methods: 2.652 patients with localiced carcinoma of prostate underwent VIP at our centre between 2001- 2006. Our current technique involves: early division of the bladder neck, preservation of the lateral pelvic fascia and control of the dorsal vein complex after apical dissection of the prostate. Oncological, functional and follow-up information was obtained through ROBOSURG® data base, which is managed by an independent group not involved in the patient care.

VIP, as it has evolved in our hands over a period of 5 years, has given excellent outcomes in terms of cancer control, continence and erectile function. Our modifications of the surgical technique had a singular focus on consistent improvement of the so called Trifecta, taking radical retropubic prostatectomy (RRP) published data as a reference standard. We present our current technique of VIP with preservation of the lateral prostatic fascia (Veil of Aphrodite).

Results: In this report we include 2077 patients with follow-up ranging from 4 weeks to 260 weeks (median 68 weeks). We have a low incidence (1.5%) of perioperative complications. 97.6% of our patients had a hospital stay of less than 48 hours. There were 5.8% unscheduled postoperative visits. With the PSA cut-off limit of 0.4ng/ml, the overall biochemical recurrence rate was 3.9%. Median duration of incontinence was 4 weeks; 0.8% patients had total incontinence at 12 months. The intercourse rate was 93% in men with no pre-operative erectile dysfunction undergoing veil nerve-sparing surgery, although only 51% returned to baseline function.

Conclusion: Vattikuti Institute Prostatectomy offers excellent patient recovery with significant reduction in first 30 days morbidity and provides excellent oncological and functional outcomes. The preservation of the Veil of Aphrodite helps in postoperative return of erectile function in patients with normal preoperative erectile function.

Key words: Robotic. Radical prostatectomy. Prostate cancer. Laparoscopy.

Introduction

Radical prostatectomy for localized carcinoma of the prostate reduces disease-specific and overall mortalities as well as the risk of metastases and local progression (1). Over past several decades RRP has consolidated as a refined surgical procedure, with excellent outcomes (2-4). Recent trends favor minimally invasive surgical techniques for removing the prostate (5,6).

Our technique, the Vattikuti Institute Prostatectomy (VIP), was implemented to the routine surgical care of patients with localized prostate cancer in 2001 (7,8) and has been widely adopted by others (9-11). In 2003 we introduced a major modification of the preservation of lateral pelvic fascia - the Veil of Aphrodite which has improved postoperative erectile function significantly (12,13). From 2001 - 2005 we have performed 2652 RRPs. In this report, we describe our current technique; early oncological and functional results in 2077 patients.

Development of V.I.P

The post PSA era has significantly contributed to the early diagnosis of prostate cancer as well as increased its cure rates. Erectile dysfunction is the most distressing adverse outcome that the patients sustain following open radical prostatectomy (14). Our technique harnesses the precision inherent in robotic surgery for better nerve preservation and resultant improved potency, without compromising cancer control.

Over a period of 5 years, we made the following modifications in our technique and found certain maneuvers helpful in achieving our objectives including division of the bladder neck initially (first done in 2001), application of a running suture for urethrovesical anastomosis (2001), and incising the prostatic fascia anterolaterally to release the nerves (2003). These techniques have resulted in a decrease in operative times, incidence of anastomotic leaks and of erectile dysfunction, respectively. In 2004 (after more than 1000 cases) we changed our technique of traction on the bladder neck and abandoned initial bulk ligation of the dorsal vein complex, in favor of precise suturing after urethral transection. Starting in 2002, we eliminated the use of monopolar cauterization after the division of the seminal vesicle. In 2004 we stopped opening endopelvic fascia, and started preserving the anterior fibromuscular stroma of the prostate in select patients with low volume disease.

Methods

PATIENT SELECTION

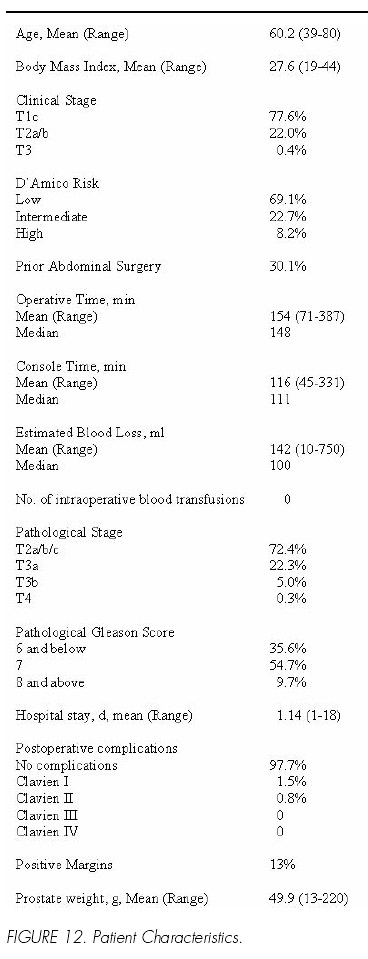

While respecting patient preferences for surgery, we generally recommend that men with low PSA and focal Gleason 6 cancer of the prostate undergo active monitoring with follow-up biopsies. We offer surgery for men with non-focal Gleason 6 cancer (35.6% of our patients), Gleason 7 (54.7%) and Gleason 8-10 cancer (9.7 %). Patients with >25% Gleason 7 disease get conventional nerve sparing (2,3) on the ipsilateral side: all others get the veil nerve sparing (12).

TECHNIQUE OF VIP (15)

Patient positioning and port placement

The patient is padded at pressure points and placed in dorsal lithotomy position. Pneumoperitoneum is created using a Veress needle and ports are placed under vision. We use a six port approach. (Figure 1) The table is then moved to steep (30 degree) Trendelenburg position.

Robotic Instruments

The operation can be done with either the 8 mm or 5 mm robotic instruments. We currently prefer the latter. We use a combination of the monopolar hook, the cold round tip scissors, a Maryland or triangular (Precise) bipolar grasper and needle holders. In patients in whom nerve-sparing is not contemplated, the scissors can be eliminated and the procedure can be done with 3 instruments, thus reducing the cost.

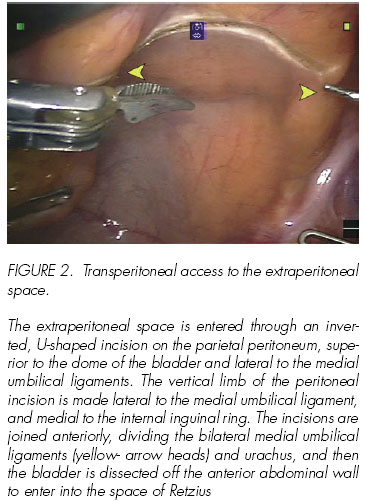

The extraperitoneal space is entered through an inverted, U-shaped incision on the parietal peritoneum, superior to the dome of the bladder and lateral to the medial umbilical ligaments. The vertical limb of the peritoneal incision is made lateral to the medial umbilical ligament, and medial to the internal inguinal ring. The incisions are joined anteriorly, dividing the bilateral medial umbilical ligaments (yellow- arrow heads) and urachus, and then the bladder is dissected off the anterior abdominal wall to enter into the space of Retzius.

Development of the extraperitoneal space

The peritoneal cavity is inspected using the 30-degree upward-looking lens. A transverse peritoneal incision is made extending from the left to the right medial umbilical ligament; this incision is extended in an inverted U to the level of the vasa on either side. The space anterior to the peritoneum and space of Retzius is thus entered. The rest of the surgery is performed in this space anterior to the peritoneal reflection of the bladder and prostate (Figure 2).

Lymph node dissection

The tissue overlying the external iliac vein is incised and lymph nodal package is pushed medially. The dissection is started at the lymph node of Cloquet in the femoral canal and continued proximally toward the bifurcation of iliac vessels. The obturator nerve lies on the floor of this dissection and is carefully preserved (Figure 3). In patients with Gleason 8-10 disease, the nodal package between the obturator nerve and the hypogastric vein is also removed.

Bladder Neck Transection

We next approach the bladder neck directly, without opening endopelvic fascia or ligating the dorsal vein complex, a modification over our previously described technique (8). This portion of the procedure is best done with a 30-degree lens looking down. The right assistant grasps the anterior bladder wall in the mid line with an atraumatic grasper, lifts it directly towards the anterior abdominal wall and the left assistant deflates the Foley balloon while keeping the catheter in the bladder. This simple maneuver aids in the identification of the bladder neck as the bladder pulls away from the prostate excepting at the midline anterior to the catheter (Figure 4). A 1 cm incision is made in the anterior bladder neck at 12 Oclock, cutting down the detrusor to expose the catheter in the mid-line (Figure 5).

A detrusor apron may be seen on the anterior surface of the prostate (17). The incision in the bladder neck is made immediately superior to the detrusor apron. After the anterior bladder neck is incised, the Foley catheter is delivered and the left-side assistant grasps the tip of the Foley catheter with firm anterior traction. This exposes the posterior bladder neck, which is then incised (Figure 6).

The posterior bladder neck is gradually dissected away from the prostate. The anterior layer of Denonvilliers fascia is now exposed. (Figure 7) and is incised precisely, exposing the vasa and the seminal vesicles. The left-side assistant provides upward traction to the posterior base of the prostate to facilitate dissection of the vasa and seminal vesicles.

First the vasa are skeletonized and transected, then held upward by the left assistant providing further traction for dissection of the seminal vesicles. The artery to the seminal vesicle is controlled by clipping or fine bipolar coagulation.

Both the vasa and seminal vesicles are then grasped and the posterior prostate is retracted upwards, allowing exposure of posterior layer of the Denonvilliers fascia. An incision is made in this fascia and a plane is developed between the posterior layer of the Denonvilliers fascia and perirectal fat. This hypo-vascular plane can be created easily using blunt dissection. The dissection is carried down to the apex of the prostate. This plane of dissection is extended laterally to expose the lateral pedicles of the prostate.

The base of the seminal vesicle is retracted superomedially by the assistant on the opposite side and the prostatic pedicle is delineated and divided. This pedicle lies anterior to the pelvic plexus and neurovascular bundle and includes only prostatic blood supply. The pedicles are controlled by either clipping or individually coagulating the vessels by bipolar cauterization.

Nerve sparing techniques: the Veil of Aphrodite

Although the classical description of the neurovascular bundles is that of two bundles of tissue that are located near the posterolateral surface of the prostate (2) there is accumulating evidence that there is variability in this complex. In some patients, rather than distinct neurovascular bundles, the cavernosal nerves form lattices or curtains that extend from the postero-lateral to the antero-lateral surface of the prostate (17-20). In order to preserve these nerves, several surgeons (4,22) and we (12) have modified nerve-sparing techniques by dissecting the prostatic fascia off the prostate postero-laterally and incising it anteriorly. We termed this approach, the veil of Aphrodite nerve-sparing technique (Aphrodite is the Greek goddess of love who causes strong men to fight over her); latterly, others have called it high anterior release, curtain dissection, or incremental nerve sparing. In the Veil procedure we accomplish this through an antegrade approach. A plane between the prostatic capsule and the prostatic fascia is developed cranially, at the base of the seminal vesicles (Figure 8). With appropriate counter-traction provided by the assistants the surgeon is able to enter a plane between the prostatic fascia and the prostate. This plane is deep to the venous sinuses of Santorinis plexus. Careful sharp and blunt dissection of the neurovascular bundle and contiguous prostatic fascia is performed using the articulated cold scissors until the entire prostatic fascia up to the pubourethral ligament is mobilized in continuity. This plane is mostly avascular, except anteriorly where the fascia is fused with the pubo-prostatic ligament, and covers the dorsal venous plexus. When performed properly, curtains of periprostatic tissue hang from the pubourethral ligament, the veil of Aphrodite (Figure 9).

If this plane is difficult to enter (patients with post-biopsy fibrosis), we perform part of the dissection retrograde, and enter the plane on the anterolateral surface of the prostatic capsule at the 10- or 2- oclock position.

Exposure of prostatic apex and control of dorsal venous complex

The prostatic apex is best visualized using the 0 degree lens; this is particularly useful in patients with an overhanging pubic symphysis. Once the lateral prostatic fascia is dissected off the prostatic apex, the right assistant retracts the prostate firmly to the patients head. The puboprostatic ligament is incised with the cold scissors where it inserts into the apical prostatic notch (Figure 10). It is important not to skeletonize the urethra as maintaining the fibrovascular support of the urethra intact hastens the return of continence. The cavernosal nerves are close to the urethra and are vulnerable to thermal or traction injury. The urethra is then dissected into the prostatic notch and transected sharply 5mm distal to the notch. The freed specimen is then placed in an EndopouchTM (Ethicon Endo-Surgery Inc.).

The dorsal venous complex is controlled with an overrunning suture of 2-0 braided polyglactin on 17 mm tapercut needle. (Figure 11). Depending on the amount of oozing from the dorsal vein complex, control is done before or after urethral transection

Urethrovesical Anastomosis

A running suture is used for the urethrovesical anastomosis. We use a minor modification of the technique described by Van Velthoven (22). One dyed and one undyed seven-inch 3-0 monofilament polyglecaprone-25 sutures on 17 mm tapercut needles are tied back to back. The suture is now double-armed with a pledget of the knots in the middle. We start with dyed arm, on the posterior bladder wall at 4 oclock position outside-in, continuing into the urethra at the corresponding site, inside-out. The dyed arm is run for two bites in the urethra and three in the bladder neck; the bladder is then cinched down to the urethra, with the right assistant following the suture. After the posterior urethral wall is approximated to the bladder neck in its entirety, the direction of the stitch is then changed to get passage of the needle from outside-in bladder to inside out. The suture is run clockwise up to 11 oclock position, and handed to the left assistant to hold with gentle, approximating traction. The undyed arm is then run counter clockwise from 4 oclock to 11 oclock. During the placement of anastomotic sutures the left assistant moves the tip of urethral Foley in an out of the urethral stump to prevent suturing of the back wall of urethra. Both arms of the suture are tied to each other to complete the anastomosis.

A new 20 French Foley catheter is introduced and its balloon is inflated to 20 cc. The bladder is filled with 250 cc saline to test the integrity of the anastomosis.

Retrieval of specimen and completion of surgery

A Jackson-Pratt drain is placed through left 5 mm port. The specimen is removed after enlarging the umbilical port incision as required. The incision is closed with interrupted sutures of 0 braided polyester. The skin is closed with self-absorbing subcuticular sutures.

Postoperative care

In order to minimize the urine spillage in to the operating field, intravenous fluids are restricted to a minimum during the surgery. All patients receive a 1000 ml bolus of intravenous fluid in recovery room. Once on the floor they start on clear liquid diet and advance to regular diet after a bowel movement. All patients are encouraged to ambulate within four hours of arrival on floor. The Jackson-Pratt drain is removed on day one and patients are discharged within 24 hours with an indwelling Foley catheter. The catheter is removed on day 7 or after under cystographic control.

Data collection and analysis

Preoperative demographic and operative data were collected prospectively in a customized database ROBOSURG®. Pathological specimens were examined by one of several individual pathologists, with randomly selected specimens being reviewed by a referee pathologist. Patients were surveyed with a mailed-in questionnaire that included IPSS and SHIM scoring sheets, and questions about pad usage and duration of incontinence. Non-respondents were followed-up persistently by the database manager through a series of periodic communications including phone call reminders. The data were analyzed with an SPSSTM (SPSS Corporation, Chicago, IL) statistical software package.

Results

Preoperative and operative parameters

From March 2001 to September 2006, we have operated on 2652 patients, 2582 at our own institution. Pre operative and operative parameters are detailed in Figure 12. In keeping with our philosophy, patients in this series had higher Gleason grade disease (64.4% > than Gleason 6) than those in many contemporary radical prostatectomy studies.

The average operative time decreased from 195 minutes (min) in the first 100 patients to 131 min in the last 100 patients, robotic console time decreased from 165 min to 92 min respectively. This decrease in times was noted despite progressively increasing house staff participation and surgical complexity (greater utilization of veil nerve sparing). The positive margin rate at the apex was 12% for the first 100 cases (23). When initial bulk ligation of the dorsal vein complex was replaced with suture ligation of the individual vessels after removal of the prostate, the apical margin rate decreased to 1.5% in patients with T2 disease.

Biochemical recurrence

Eighty one patients of the 2077 patients with a median follow up of 68 weeks and mean follow up of 82 weeks (range 4-260 weeks) had a biochemical recurrence. The BCR rate was 3.9% with the median time to recurrence of 32 weeks (mean 54 weeks, range 0- 263weeks) (24). The biochemical recurrence free survival (BRFS) probabilities at 1, 3 and 5 years are 97%, 93% and 92% respectively. Time to BCR and BRFS probabilities are represented in the Kaplan-Meir curves for overall BRFS (Figure 13), by preoperative PSA (Figure 14), Organ confined status (Figure 15) and Pathological Gleason score (Figure 16). On multivariable analysis, preoperative PSA, pathologic Gleason score, percent tumor volume and non-organ confined status were significant factors affecting time to biochemical recurrence.

Return of continence

95.2% of patients were continent at the end of 12 months. We considered patients to be continent if they were not using any pads or if they used a safety liner for security reasons. About 26 % patients were totally dry at the time of catheter removal. 55 % of our patients were dry at 4 weeks postoperatively. Only 1.1% of patients required the use of 2-3 pads per day at the end of 12 months. Of these, 4 had collagen injections and 3 opted to have artificial urinary sphincters. The mean pre-operative IPSS and Quality of Life scores (7.7 and 1.66) were significantly more than the post operative values.(6.5 and 1.5, P <0.002 and <0.02). Incontinent patients had a higher rate of anastomotic stricture (6.6% vs 0.71 %) or post-operative radiation therapy (9.09% vs 2.41%).

Return of potency

42% of patients underwent standard nerve sparing on both sides. 25% of patients had a unilateral veil of Aphrodite with contralateral standard nerve sparing. 33% of patients underwent a bilateral incremental nerve sparing operation. Patients undergoing bilateral veil of Aphrodite had significantly better return of potency than patients with conventional nerve sparing surgery (Figure 17). In patients with no pre-operative erectile dysfunction (SHIM>21), intercourse was reported in 70 and 100 percent of the patients undergoing bilateral veil nerve-sparing surgery at 12 and 48 month follow-up respectively, although only half of these patients attained normal SHIM score off medication.

Post-operative potency rates in patients with no-, mild- and moderate erectile dysfunction preoperatively were analyzed. As expected, potency rates were higher in patients who had no erectile dysfunction pre-operatively. This trend was seen in patients undergoing both, standard or veil of Aphrodite (unilateral or bilateral) nerve-sparing procedures. Regardless of pre-operative erectile function, patients undergoing veil of Aphrodite (unilateral or bilateral) nerve-sparing had better potency outcomes than patients undergoing conventional nerve-sparing prostatectomy (Figure 18).

Complications

Our analysis of perioperative complications reveals a low incidence of complications. The mean hospital stay for patients undergoing VIP is 1.1 days with 97.6% of patients being discharged home within 48 hours. There were 5.8% unscheduled postoperative visits, mostly for urinary retention following early catheter removal.

We have never had to transfuse any patient intraoperatively and our postoperative transfusion rate is 1.5%. The most disturbing complication in our series is symptomatic postoperative urinary leaks (1.8%). Because we use an intraperitoneal approach, these patients develop significant urinary peritonitis. Clinical presentation in such patients is very dramatic. Although half these patients were managed conservatively with nasogastric decompression and bowel rest, the other half needed CT guided drainage of urinomas and prolonged Foley catheterization. Only 0.8% patients had Clavien grade 2 [25] postoperative complications requiring any intervention. Overall, VIP in our hands is a very safe procedure with a major complication rate of 1.5%.

Conclusion

Radical retropubic prostatectomy has evolved over the last three decades to a precise, sophisticated procedure with minimal mortality and excellent surgical outcomes. Our own experience suggests that equally good results can be obtained with robotic assistance. Our technique, Vattikuti Institute Prostatectomy (VIP) continues to evolve with experience, much as open radical prostatectomy does. In our hands, the veil nerve-sparing offers superior erectile function than conventional nerve-sparing surgery without compromising cancer control. It is our preferred technique in potent men with low-or moderately aggressive prostate cancer.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alok Shrivastava for illustrations and Fred Muhletaler in preparation of the manuscript.

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Mahendra Bhandari M.D.

Vattikuti Urology Institute

Henry Ford Health System

2799 West Grand Blvd.

Detroit, MI, 48202, USA.

mbhanda1@hfhs.org

References and recommended readings (*of special interest, **of outstanding interest)

1. BILL-AXELSON, A.; HOLMBERG, L.; RUTTU, M. y cols.: Radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. N. Eng. J. Med., 352: 1977, 2005. [ Links ]2. WALSH, P.C.; LEPOR, H.; EGGLESTON, J.C.: Radical prostatectomy with preservation of sexual function: anatomical and pathological considerations. Prostate, 4: 473, 1983. [ Links ]

3. WALSH, P.C.; MARSCHKE, P.; RICKER, D. y cols.: Patient-reported urinary continence and sexual function after anatomic radical prostatectomy. Urology, 55: 58, 2000. [ Links ]

4. GRAEFEN, M.; WALZ, J.; HULAND, H.: Open retropubic nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. Eur. Urol., 49: 38, 2006. [ Links ]

5. ABBOU, C.C.; SALOMON, L.; HOZNEK, A. y cols.: Laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: preliminary results. Urology, 55: 630, 2000. [ Links ]

6. GUILLONNEAU, B.; VALLANCIEN, G.: Laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: the Montsouris technique. J. Urol., 163: 1643, 2000. [ Links ]7. MENON, M.; SHRIVASTAVA, A.; TEWARI, A. y cols.: Laparoscopic and robot assisted radical prostatectomy: establishment of a structured program and preliminary analysis of outcomes. J. Urol., 168: 945, 2002. [ Links ]

**8. MENON, M.; TEWARI, A.; PEABODY, J. y cols.: Vattikuti Institute prostatectomy: technique. J. Urol., 169: 2289, 2003. [ Links ]

9. AHLERING, T.E.; SKARECKY, D.; LEE, D. y cols.: Successful transfer of open surgical skills to a laparoscopic environment using a robotic interface: initial experience with laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. J. Urol., 170: 1738, 2003. [ Links ]

10. PATEL, V.R.; TULLY, A.S.; HOLMES, R. y cols.: Robotic radical prostatectomy in the community setting the learning curve and beyond: initial 200 cases. J. Urol., 174: 269, 2005. [ Links ]

11. SMITH, J.A. Jr.: Robotically assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy: an assessment of its contemporary role in the surgical management of localized prostate cancer. Am. J. Surg., 188: 63, 2004. [ Links ]*12. KAUL, S.; BHANDARI, A. y cols.: Robotic radical prostatectomy with preservation of the prostatic fascia: a feasibility study. Urology, 66: 1261, 2005. [ Links ]

*13. MENON, M.; KAUL, S. y cols.: Potency following robotic radical prostatectomy: a questionnaire based analysis of outcomes and conventional nerve sparing and prostactic fascia sparing technique. J. Urol., 174:2291, 2005. [ Links ]

14. SARANCHUK, J.W.; KATTAN, M.W.; ELKIN, E. y cols.: Achieving optimal outcomes after radical prostatectomy. J. Clin. Oncol., 23: 4146, 2005. [ Links ]

**15. MENON, M.; SHRIVASTAVA, A. y cols.: Vattikuti institute prostatectomy: contemporary technique an analysis of results. Euro. Urol., 51: 648, 2007. [ Links ]

**16. MYERS, R.P.: Detrusor apron, associated vascular plexus, and avascular plane: relevance to radical retropubic prostatectomy-anatomic and surgical commentary. Urology, 59: 472, 2002. [ Links ]

17. TEWARI, A.; PEABODY, J.O.; FISCHER, M. y cols.: An operative and anatomic study to help in nerve sparing during laparoscopic and robotic radical prostatectomy. Eur. Urol., 43: 444, 2003. [ Links ]

18. TAKENAKA, A.; MURAKAMI, G.; SOGA, H. y cols.: Anatomical analysis of the neurovascular bundle supplying penile cavernous tissue to ensure a reliable nerve graft after radical prostatectomy. J. Urol., 172: 1032, 2004. [ Links ]

19. COSTELLO, A.J.; BROOKS, M.; COLE, O.J.: Anatomical studies of the neurovascular bundle and cavernosal nerves. BJU Int., 94: 1071, 2004. [ Links ]

20. KIYOSHIMA, K.; YOKOMIZO, A.; YOSHIDA, T. y cols.: Anatomical features of periprostatic tissue and its surroundings: a histological analysis of 79 radical retropubic prostatectomy specimens. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol., 34: 463, 2004. [ Links ]

21. LUNACEK, A.; SCHWENTNER, C.; FRITSCH, H. y cols.: Anatomical radical retropubic prostatectomy: curtain dissection of the neurovascular bundle. BJU Int., 95: 1226, 2005. [ Links ]

22. VAN VELTHOVEN, R.F.; AHLERING, T.E.; PELTIER, A. y cols.: Technique for laparoscopic running urethrovesical anastomosis: the single knot method. Urology, 61: 699, 2003. [ Links ]

23. MENON, M.; SHRIVASTAVA, A.; SARLE, R. y cols.: Vattikuti Institute Prostatectomy: a single-team experience of 100 cases. J. Endourol., 17: 785, 2003. [ Links ]

24. STEPHENSON, A.J.; KATTAN, M.W.; EASTHAM, J.A. y cols.: Defining biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy: a proposal for a standardized definition. J. Clin. Oncol., 24: 3973, 2006. [ Links ]

25. CLAVIEN, P.A.; SANABRIA, J.R.; STRASBERG, S.M.: Proposed classification of complications of surgery with examples of utility in cholecystectomy. Surgery, 111: 518, 1992. [ Links ]

texto en

texto en