My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Archivos Españoles de Urología (Ed. impresa)

Print version ISSN 0004-0614

Arch. Esp. Urol. vol.60 n.6 Jul./Aug. 2007

INTERNATIONAL SECTION

Extragonadal retroperitoneal germ cell tumor: primary versus metastases?

Tumor de células germinales extragonadal retroperitoneal. ¿Tumor primario o metastásico?

David Parada1, Karla B. Peña1, Otto Moreira2, Iván Cohen1, Arelí M Parada3 and Luis D. Mejías4

1Department of Anatomic Pathology. Vargas Hospital. Caracas. Venezuela.

2Service of Urology. Vargas Hospital. Caracas. Venezuela.

3School of Medicine, José María Vargas. Central University of Venezuela. Caracas. Venezuela.

4Cupira´s Hospital. Miranda. Venezuela.

SUMMARY

Objetive: Primary extragonadal germ cell tumors are rare and their histogenetic origin is not clear. We describe two cases presenting as primary retroperitoneal germ cell tumors without clinical evidence of testicular tumor.

Methods: A 21 and 18 years-old patients presented retroperitoneal choriocarcinoma and yolk sac tumor, respectively. In both cases, testicular palpation was not suspicious for testicular cancer. Testicular ultrasound founded alterations in right testes.

Results: A right orchitectomy were performed and the final diagnostics were mature teraroma associated with intratubular malignant germ cell.

Conclusions: Adult mature teratoma is infrequent and the retroperitoneal germ cell tumors should be considered to be metastases of a viable or burned–out testicular cancer.

Keywords: Germ cell tumor. Retroperitoneal. Testicular tumor. Gonadal teratoma. Intratubular germ cell neoplasia of testis.

RESUMEN

Objetivo: Los tumores primarios de células germinales extragonadales son poco frecuentes y su origen histogenético no está claro. Describimos dos casos que se presentaron como tumores de células germinales retroperitoneales sin evidencia clínica de tumor testicular.

Métodos: Dos pacientes de 21 y 18 años presentaron respectivamente un coriocarcinoma y un tumor del saco embrionario retroperitoneales. En ambos casos, la palpación testicular no era sospechosa de cárcel testicular. La ecografía testicular descubrió alteraciones en los testículos derechos de ambos pacientes.

Resultados: Se llevó a cabo orquiectomía derecha con el diagnóstico final de teratoma maduro asociado con células germinales malignas intratubulares.

Conclusiones: El teratoma maduro del adulto es poco frecuente, y los tumores de células germinales retroperitoneales deben ser consideradas metástasis de un cáncer testicular fundido.

Palabras clave: Tumor de células germinales. Retroperitoneo. Tumor testicular. Teratoma gonadal. Neoplasia de células germinales intratubular.

Introduction

Primary extragonadal germ cell tumors (EGCT) are rare and account a small percentage, 2% to 5%, of all germ cell tumors (1,2). In adults, these tumors have been reported in many sites, including the retroperitoneum (3-9), the anterior mediastinum (8-13) and the pineal gland (7,8). Thus, they arise mostly along the sagital midline. The histogenetic origin of primary extragonadal germ cell tumors is still a matter of debate and it remains uncertain whether such tumors develop primary at extragonadal sites or represent metastases of a primary testicular tumor.

Previous studies of retroperitoneal germ cell tumors have showed intratubular germ cell neoplasia (IGCN), testicular scarring or an invasive testicular tumor, suggesting that the testicular tumor was primary (2,14-16). Therefore, it may be important to exclude testicular pathology when treating a primary retroperitoneal germ cell tumor. Here in, we study two cases presenting as primary retroperitoneal germ cell tumors without clinical evidence of testicular tumor.

Clinical data

Case 1

A 21-year-old patient referred a six-month history of constant, colic, left flank pain, and fever. His medical history was unremarkable. Abdominal palpation revealed tumor localized in left hemiabdomen. An abdominal ultrasound showed left ureterohydronephrosis grade I and renal exclusion was demonstrated by gammagraphy (Figure 1,A). The patient leaved the hospital two days after his admission. He presented clinical symptoms of lower respiratory infection and returned to our hospital. A chest radiogram and a toracic computerized tomography, showed multiple nodular images, consistent with metastases (Figure 1,B). A CT scan of the abdomen demonstrated a retroperitoneal mass (maximun diameter: 30 cm) (Figure 1,C). A tomography guided biopsy was performed and histological examination showed choriocarcinoma. Serum levels of alpha fetoprotein, human chorionic gonadotropin and lactate dehydrogenase were 221,65 IU/ml (normal value, 0-15 IU/ml), 155697,74 IU (normal value, 0-20 IU/ml), and 1521 IU/ml (normal value, 89-221 IU/ml), respectively. Testicular palpation was not suspicious for testicular cancer. Testicular ultrasound founded an hypoechoic zone at the right testis (Figure 1,D). A radical orchydectomy was performed. Two days after surgical intervention the patient has acute respiratory distress.

At autopsy, a retroperitoneal tumor with extense necrosis and hemorrhagic was seen. Additionally, the lungs, liver and a right parahiliar thoracic lymph node showed nodular lesions (meassure range between 1 to 4 cm in diameter), suspicious for metastases.

Case 2

A 18 years old patient referred a two months history of diffuse abdominal pain, diarrhea and vomits. In December 2005, he had an apendicectomy. The remainder medical history was unremarkable. Abdominal physical examination showed difuse pain with rigidity. Clinical diagnosis was intra-abdominal abscess. A laparotomy was performed and an abdominal tumor was seen. The biopsy showed yolk sac tumor. A CT scan of the abdomen showed retroperitoneal tumor with hypocaptation areas (necrosis) (Figure 1,E). Serum levels of alpha fetoprotein and human chorionic gonadotropin were 309 IU/ml (normal value, 0-15 IU/ml) and 0.50 IU/ml (normal value, 89-221 IU/ml), respectively. Testicular palpation was not suspicious for testicular abnormalities. Testicular ultrasound founded an hypoechoic lesion at the right testis (Figure 1,F). A radical orchidectomy was performed. The patient is alive and receiving chemotherapy treatment.

Materials and methods

The pathological specimens were fixed in buffer formalin pH 7.2, and tissue preparations were made by the routine procedure to hematoxylin-eosin stain. Paraffin-embedded preparation was stained immunohistochemically using antibodies for pan-cytokeratin (AE1/AE3, 1:50, Dako,Glostrup,Denmark), Vimentin (1:100, Dako,Glostrup,Denmark), Alpha-Feto protein (Prediluted,Glostrup,Denmark) and Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (Prediluted,Glostrup,Denmark). Enzyme-conjugated polymer system (EnVision System, Dako,Glostrup, Denmark) was performed. Orchidectomy specimens were completely submitted to histologic study.

Results

Pathologic Findings, Case 1

The retroperitoneal biopsy showed a tumor composed of syncitiotrophoblastic and cytotrophoblastic elements, wich were present in the typical biphasic plexiform pattern. Necrosis was seen (Figure 2 A,B). Immunohistochemically, an intense cytoplasmic reactivity to human chorionic gonadotropin was present (Figure 2 B). The diagnosis of choriocarcinoma was concluded. The right orchidectomy showed a cystic tumor (Maximun diameter: 6 mm) with mucous content and mixture elements (nerve, muscle, gastrointestinal and cutaneous epithelium). No cytologic atypia, mitotic activity, fibrosis or sclerosis was present (Figure 2,C). Adjacent seminiferous tubules contained atypical germ cells charactherized by enlarged, hyperchromatic nuclei, with one or two prominent nucleoli, thickened nuclear membranes and clear cytoplasm (Figure 2,D). The final diagnosis was mature teroma associated with intratubular malignant germ cell (IGCN).

At the autopsy, a retroperioneal tumor, involving the aorta, was detected. Cut section, showed extensive necrosis and hemorrhagic areas (Figure 2,E). Both lungs showed multiple nodular lesions, without specific distribution (Maximun diameter: 4 cm); cut section presented similar findings that retroperitoneal tumor (Figure 2,F). Histologic analysis demonstrated a choriocarcinoma, with no other component. A pulmonar parahiliar lymph node showed a metastatic neoplasm consisting of sheets of uniform cells with clear cytoplasm and well-defined borders. Focally, a papillary component was identified. These findings were consistent with the diagnostic of yolk sac tumor, solid pattern.

Pathologic Findings, Case 2

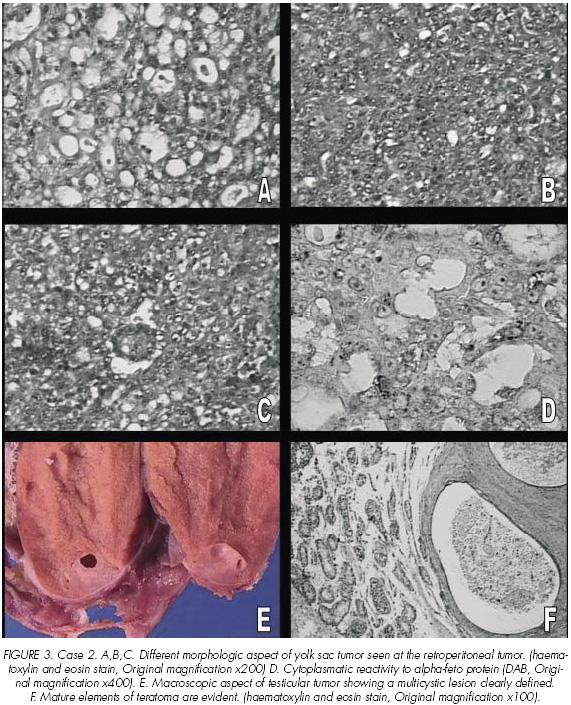

The intraabdominal biopsy showed a tumor composed of different patterns. In some areas, the tumor was characterized by intracellular vacuoles with a spiderweb-like array. This pattern was intermingled with solid areas of yolk sac tumor. Besides to these findings, another pattern consisted of a central vessel rimmed by fibrous tissue surrounded by malignant epithelium (Figure 3 A,B,C). A strong cytoplasmatic reactivity to alpha-feto protein was evident (Figure 3D). The final diagnostic was yolk sac tumor.

The right orchidectomy showed a multi-cystic tumor (Maximun diameter: 6 mm) with mucous content (Figure 3 E). Histologic findings were similar to the orchidectomy previously described in case 1. The seminiferous tubules around the tumor contained intratubular malignant germ cells (Figure 3 D).

Discussion

Although there is no clear explanation regarding the histogenesis of germ cell tumors, there are many theories. The most accepted theory suggests that these tumors originate from displaced primordial germ cells situated along the midline of the body (3). An alternative explanation for EGCT is the presence of metastases from primary testicular lesions. Whether these tumors are trully extragonadal, synchronous germ cell tumors in the testis or metastatic lesions is still matter of debate.

The differentiation of a primary testicular neoplasm metastazing to retroperitoneum from a primary extragonadal germ cell tumor, probably, depends of an adequate testicular examination. In both our cases, clinical urological examination did not demonstrate alterations on testicular palpation, but ultrasound evaluation demonstrated alterations of the testes. Similar findings have been reported by Comiter (17) and Scholz (2), who have founded ultrasonographical alterations in 91% of patients with unsuspicious testes on palpation.

In so-called clinically extragonadal retroperitoneal germ cell tumors, Azzopardi (18) and Scholz (2) reported that some normal palpable testes have either scar tissue or small foci of tumor on histological examination. Our histopathologic findings of the testes show evidence of viable tumor and IGCN. These may indicate that EGCT represent metastases from testicular tumors. Additionally, the identification of a primary testicular tumor in patients with a presumed extragonadal germ cell tumor is important beause it carries the danger of persistent testicular malignancy in up to 50 % of such patients despite systemic chemotherapy (2,15,17,19).

In 2002 Scholz (2) reported testicular histological abnormalities in all of his patients. In this serie, the most common testicular neoplasia was IGCN, seminoma and teratoma (without no other specification), respectively. In our cases an interesting finding was mature teratoma associated with IGCN. The presence of mature teratoma may be a pronostic challenge. In this respect, the World Health Organization has dropped the subclassification of teratomas into mature and immature subtypes (20). No useful prognostic information was provided by this distinction.

Probably, the age of occurrence in testicular teratomas appears to play a role in the behaviour of testicular teratomas (20). In post-puberal patients, testicular teratoma has a malignant clinical course and the pediatric case has a benign outcome (21). The benign or malignant germ cell could be the difference between these groups. In adults, testicular teratomas derive from germ cells that have undergone malignant transformation and most of the time probably evolve from invasive malignant germ cell tumors of conventional type (20). In contrast, the pediatric testicular teratomas derive from a benign germ cell (22,23). Two histopathological findings support these considerations. First, the presence of IGCN is frequently seen in adult patients, but it has not been reported in pediatric patients (20,24). Second, post-puberal teratoma shows cytologic atypia and mitotic activity in differentiated tissues (20). These findings are relatively uncommon in pediatric teratomas. The histological analysis from the orquidectomy and the presence of metastases, in our patients, are consistent with the aggressive biologic behaviour in post-puberal teratomas and, probably the origin was a malignant germ cell due to the presence of IGCN associated with mature teratoma.

Our patients were reported as mature testicular teratomas, but this tumor is uncommon as a pure tumor (20). The presence of testicular teratoma is a common component of mixed germ cell tumor (25). A possible explanation of pure teratomas in adults patients is regression of non-teratomatous components, a relatively common phenomenon in testicular germ cell tumors (20). The regressive changes can be histological identified as scar tissue, sclerosis or fibrosis (2). In our study we did not find areas consistent with regression.

In summary, our cases reinforce the concept that the so-called primary retroperitoneal germ cell tumors are rare and they should be considered to be metastases of a viable or burned–out testicular cancer. The post-puberal or adult mature testicular teratomas are infrequent and when the diagnosis is made, this neoplasm may be associated with germ cell tumor metastases of either teratomatous or nonteratomatous types. Finally, an intensive urological examination including testicular ultrasound in patients with retroperitoneal germ cell tumor is mandatory.

References and recomended readings (*of special interest, **of outstanding interest)

1. COLLINS, D.; PUGH, R.: Classification and frequency of testicular cancer. Br. J. Urol., 36: 1, 1964. [ Links ]

**2. SCHOLZ, M.; ZEHENDER, M.; THALMANN, G. y cols.: Extragonadal retroperitoneal germ cell tumor: evidence of origin in the testis. Ann. Oncol., 13: 121, 2002. [ Links ]

3. FRIEDMAN, N.: The comparative morphogenesis of extragenital and gonadal teratoid tumors. Cancer, 4: 265, 1951. [ Links ]

4. PHALAKORNKULE, S.; WOODRUFF, M.: Extragonadal retroperitoneal seminoma. J. Urol., 91: 579, 1964. [ Links ]

5. ABELL, M.; FAYOS, J.; LAMPE, I.: Retroperitoneal germinomas (seminomas) without evidence of testicular involvement. Cancer, 18: 273, 1965. [ Links ]

6. BLISS, W.; BARNETT, W.: Retroperitoneal germinomas (seminomas) without evidence of testicular involvement. Am. J. Surg., 120: 363, 1970. [ Links ]

*7. UTZ, D.; BUSCEMI, M.: Extragonadal testicular tumors. J. Urol., 105: 271, 1971. [ Links ]

8. JOHNSON, D.; LANERI, J.; MOUNTAIN, C. y cols.: Extragonadal germ cell tumors. Surgery, 73: 85, 1973. [ Links ]

9. CHA, E.: Ectopic seminoma (germinoma) in the retroperitoneum and mediastinum: with emphasis on the lymphangiogram. J. Urol., 110: 47, 1973. [ Links ]

10. SCHLUMBERGER, H.: Teratoma of anterior mediastinum in group of military age: study of 16 cases and review of theories genesis. Arch. Pathol., 41: 398, 1946. [ Links ]

11. COX, J.: Primary malignant germinal tumors of the mediastinum: a study of 24 cases. Cancer, 36: 1162, 1975. [ Links ]

*12. HAILEMARIAM, S.; ENGELER, D.; BANWART, F. y cols.: Primary mediastinal germ cell tumor with intratubular germ cell neoplasia of the testis-further support for germ cell origin of these tumors. Cancer, 79: 1031, 1997. [ Links ]

*13. WEIDNER, N.: Germ-cell tumors of the mediastinum. Sem. Diag. Pathol., 16: 42, 1999. [ Links ]

**14. BURT, M.; JAVADPOUR, N.: Germ-cell tumors in patients with apparently normal testes. Cancer, 47: 1911, 1981. [ Links ]

15. BÖHLE, A.; STUDER, U.; SONNTAG, R. y cols.: Primary or secondary extragonadal germ cell tumor. J. Urol., 135: 939, 1986. [ Links ]

16. DAUGAARD, G.; RORTH, M.; VON DER MAASE, H. y cols.: Managent of extragonadal germ-cell tumors and the significance of bilateral testicular biopsies. Ann. Oncol., 3: 283, 1992. [ Links ]

*17. COMITER, C.; RENSHAW, A.; BENSON, C.: Burned out primary testicular cancer : sonographic and pathological characteristics. J. Urol., 156: 85, 1996. [ Links ]

18. AZZOPARDI, J.; MOSTOFI, F.; THEISS, E.: Lesions of testis observed in certain patients with widespread choriocarcinoma and related tumors. Am. J. Pathol., 38: 207, 1961. [ Links ]

19. CULINE, S.; THEODORE, C.; TERIER-LACOMBE, M. y cols.: Primary chemotherapy in patients with nonseminomatous germ cell tumors of the testis and biological disease only after orchidectomy. J. Urol., 155: 1296, 1996. [ Links ]

**20. ULBRIGHT, T.: Gonadal teratomas. A review and speculation. Adv. Anat. Pathol., 11: 10, 2004. [ Links ]

*21. GRADY, R.; ROSS, J.; KAY, R.: Epidemiological features of testicular teratoma in a prepubertal population. J. Urol., 158: 1191, 1997. [ Links ]

21. BUSSEY, K.; LAWCE, H.; OLSON, B. y cols.: Chromosome abnormalities of eighty-one pediatric germ cell tumors: sex, age, site, and histopathology-related differences a Children´s Cancer Group study. Genes. Chromosomes. Cancer., 25: 134, 1999. [ Links ]

*23. MOSTERT, M.; ROSENBERG, C.; STOOP, H. y cols.: Comparative genomic and in situ hybridization of germ cell tumors of the infantile testis. Lab. Invest., 80: 1055, 2000. [ Links ]

*24. MANIVEL, J.; REINBERG, Y.; NIEHANS, G. y cols.: Intratubular germ cell neoplasia in testicular teratomas and epidermoid cysts. Correlation with prognosis and possible biologic significance. Cancer, 64: 715, 1989. [ Links ]

**25. ULBRIGHT, T.: Neoplasms of the testis. Urologic surgical pathology. 1st ed. Bostwick D.G. and Eble J.N. (eds). Mosby. St. Louis. pp 567, 1997. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

David Parada D, MD, MSc, PhD

Department of Anatomic Pathology

Vargas Hospital

San Francisquito a Monte Carmelo

Esquina El Recodo. San José

Apdo. 1010, Caracas. (Venezuela).

parada@cantv.net

Acepted for publication: October 23th, 2006.