Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Nefrología (Madrid)

versión On-line ISSN 1989-2284versión impresa ISSN 0211-6995

Nefrología (Madr.) vol.32 no.2 Cantabria 2012

C1q nephropathy and malignancy

Dear Editor,

C1q nephropathy (C1qN) is an idiopathic glomerular disease characterized by extensive mesangial deposition of C1q with associated mesangial immune complexes, in the absence of evidence of systemic lupus erythematosus.1

The prevalence of C1qN has been estimated from 0.2% to 16%.1-9 Light microscopy (LM) findings range from no glomerular abnormalities to mesangial proliferation1,6-9,11,12 or focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSG).2-4,6-8,13 Clinical presentations vary from asymptomatic urinary anomalies,5,7,8,11,13 and macroscopic hematuria,14 to nephritic syndrome3,15 and corticorresistent nephrotic syndrome (NS).1,2-4,6-8 Earlier reports found a poor response to steroids and a high risk of progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD),1,3,6,12,15 particularly those with FSG. Patients presenting asymptomatic urinary anomalies have been found to have a good prognosis.2-5,7,8 The variability in the prevalence, clinical presentation and prognosis of C1qN has been attributed to different ages and ethnicities of the patients included in the series, and to different thresholds to perform a renal biopsy.

The association between NS and malignancy has been reported in various glomerulopathies, but not with C1qN. Recognition of malignancy-associated glomerulopathies is important to prevent ineffective and potentially harmful treatment.

A 56-year-old male was admitted to our Department with NS. He reported persistent peripheral edema lasting for two months. He was a smoker of 80 packs/year. He had exuberant edema of lower extremities and abdominal wall. Laboratory findings revealed hypoalbuminemia (1.1g/dL), proteinuria (10g/day) and microscopic hematuria; serum creatinine was 1.1mg/dL and urea: 48mg/dL. Hyperlipidemia (total-cholesterol: 326mg/dL) was also noted. HBs-antigen, HCV-antibody and HIV-antibody were all negative. Serum protein electrophoresis was unremarkable; complement levels, ANCA, ANA, cryoglobulins and anti-phospholipid antibodies were normal. Ultrassonography of the kidneys was unremarkable. Abdominal ultrassonography showed small volume ascites, and chest X-ray revealed small pleural effusions, without any other abnormal findings.

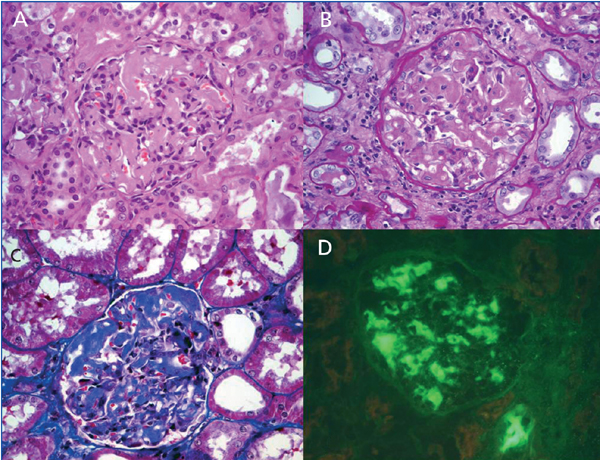

A renal biopsy was performed, whose histological findings are shown in Figure 1. Fifteen glomeruli were observed, showing segmental thickening of glomerular basement membranes (GBM) and mesangium by an eosinophilic Congo-red negative amorphous material. Spike formation or stippling of the GBM was absent in periodic-acid methenamine-silver staining. Immunofluorescence (IF) revealed predominant presence of comma-shaped C1q mesangial deposits.

Figure 1. Kidney biopsy specimen.

H&E (A), PAS (B) and Masson trichrome (C) magnification x 400, show segmental thickening

of glomerular basement membranes and mesangium by an eosinophilic amorphous material,

without mesangial hypercellularity. Immunofluorescence study (x 400)

revealed predominant mesangial deposits of C1q (D).

We started prednisolone (1mg/Kg/day), cyclosporine (3mg/Kg/day) and acenocumarol. One month later, he had an acute pyelonephritis, with worsening renal function (creatinine: 1.6mg/dL). Prednisolone dose was reduced to 0.5mg/Kg/day.

Two months later, his clinical condition deteriorated, with asthenia, anorexia and anasarca. Laboratory findings revealed a serum creatinine of 3.9mg/d, with proteinuria (39g/day) and hypoalbuminemia (1.1g/dL); trough levels of cyclosporine were 176ng/mL. In an attempt to reduce proteinuria, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were tried, without response. Cyclosporine was stopped and a right nephrectomy was performed. FSG was noted in all of the 15 glomeruli, with persistence of mesangial C1q deposits. Itis plausible that the first biopsy was not representative, or maybe this findings represented the rapid course of the disease.

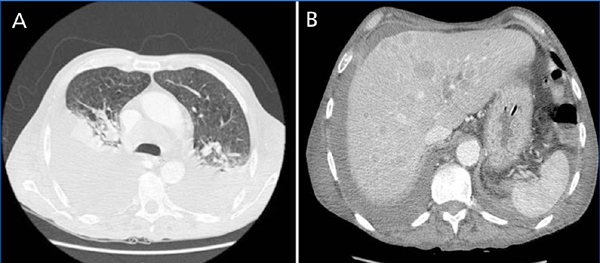

In the post-operative period, the patient developed signs of hyperhydration and started haemodialysis. Hypoalbuminemia and signs of hyperhidration gradually improved, but he maintained severe proteinuria. When clinical euvolemia was achieved, a right pleural effusion persisted. A CT scan was performed, revealing a disseminated neoplasm (Figure 2). A pleural exudate without malignant cells was drained. Tumor markers Ca 19.9 (95.2U/L, normal <27U/L) and neuron specific enolase (NSE) (96.6U/L, normal <15.2U/L) were elevated.

Figure 2. CT scan

CT scan shows bilateral pleural effusion, with atelectasis of the lower right and lower left lung lobes,

associated with lymphatic mediastinal metastases (A), and multiple diffuse hepatic nodules (B).

The patient's general condition rapidly deteriorated with marked cachexy and, later on, respiratory failure. Invasive investigation was not possible, as the patient was not fit. A week later, he died with a nosocomial respiratory infection. Histological characterization of the neoplasm was not possible, as the patient's family refused an autopsy.

C1qN can present with NS, typically with histological phenotype of either MCD or FSG. In a report of 15 pediatric patients with C1qN, 9 children had corticorresistent NS. FSG was diagnosed in four cases with poor outcome.3 Markowitz et al.2 reported 19 patients with C1qN, 79% of which with nephrotic proteinuria. Renal biopsy disclosed FSG in 17 patients and MCD in two. Four patients with FSG had progressive renal insufficiency and two developed ESRD within 27 months. In a report of 20 pediatric patients, 70% presented nephrotic range proteinuria.4 The most common histological phenotypes were FSG (40%) and MCD (30%). Patients with FSG had poor prognosis, with half progressing to ESRD in 3 years. In the report of Vizjak et al.7 comprising 72 kidney biopsies with C1qN, FSG was found in 11 patients with NS, 33% which progressed to ESRD within 2.9 years. Hisano et al.8 reported a lower prevalence of NS (41%) among 61 Japanese patients with C1qN. The prevalence of MCD in the nephrotic group was 92%, while FSG corresponded only to 8% of the cases. The majority of the patients in nephrotic group were frequent relapsers, but only 4% progressed to ESRD.

A paraneoplastic syndrome is usually inferred when glomerular proteinuria develops in the six months before or after the diagnosis of malignancy. In our patient, initial evaluation didn't provide any clue to an underlying diagnosis of malignancy. His systemic manifestations were attributed to severe protein loss, as well as to prolonged periods of hospitalization. Five months after the diagnosis of NS, a right pleural effusion persisted after achievement of euvolemia, and a CT was performed showing a disseminated neoplasm. The patient's clinical condition had markedly deteriorated and he died of sepsis and respiratory failure within a week.

Previous immunossupressive therapy may have triggered tumor cells, and promote the rapid and inexorable outcome. The patient was a heavy smoker, a known risk factor for several types of neoplasm, including lung and gastrointestinal tract carcinomas, the most frequently associated with paraneoplastic glomerulopathies. He also had high levels of NSE and Ca 19.9, which can be found in gastrointestinal and lung cancers.

Failure to recognize paraneoplastic glomerulonephritis can subject patients to ineffective and potentially harmful therapy. It is important to highlight the possible association between C1qN and malignancy. Before refractory NS associated with C1qN, an underlying malignancy should be suspected.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest associated with this manuscript.

Sofia Rocha1, M. João Carvalho1, Luísa Lobato1, Josefina Santos1, Guilherme Rocha1, Ramón Vizcaíno2, António Cabrita1

1Department of Nephrology. Hospital de Santo António, Centro Hospitalar do Porto. Porto (Portugal)

2Department of Pathology. Hospital de Santo António, Centro Hospitalar do Porto. Porto (Portugal)

Referencias Bibliográficas

1. Jennette JC, Hipp CG. C1q nephropathy: a distinct clinical pathologic entity usually causing nephrotic syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis 1985;6(2):103-10. [ Links ]

2. Markowitz G, Schwimmer J, Stokes M, Nasr S, Seigle RL, Valeri AM, et al. C1q nephropathy: A variant of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int 2003;64:1232-40. [ Links ]

3. Iskandar SS, Browning MC, Lorentz WB. C1q nephropathy: a pediatric clinicopathologic study. Am J Kidney Dis 1991;18(4):459-65. [ Links ]

4. Lau K, Gaber L, Santos N, Wyatt R. C1q nephropathy: features at presentation and outcome. Pediatr Nephrol 2005;20:744-9. [ Links ]

5. Nishida M, Kawakatsu H, Okumura Y, Hamaoka K. C1q nephropathy with asymptomatic urine abnormalities. Pediatr Nephrol 2005;20(11):1669-70. [ Links ]

6. Kersnik LT, Kenda RB, Avgustin CM, Ferluga D, Hvala A, Vizjak A. C1Q nephropathy in children. Pediatr Nephrol 2005;20(12):1756-61. [ Links ]

7. Vizjak A, Ferluga D, Jennette, Hvala A, Lindic J, Levart TK, et al. Pathology, clinical presentations, and outcomes of C1q nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 2008;19:2237-44. [ Links ]

8. Hisano S, Fukuma Y, Segawa Y, Niimi K, Kaku Y, Hatae K, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation and outcome of C1q nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2008;3:1637-43. [ Links ]

9. Roberti I, Baqi N, Vyas S. A single-center study of C1q nephropathy in children. Pediatr Nephrol 2009;24:77-82. [ Links ]

10. Wong CS, Fink CA, Baechle J, Harris AA, Staples AO, Brandt JR. C1q nephropathy and minimal change nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 2009;24:761-7. [ Links ]

11. Davenport A, Maciver AG, Mackenzie JC. C1q nephropathy: do C1q deposits have any prognostic significance in the nephrotic syndrome? Nephrol Dial Transplant 1992;7(5):391-6. [ Links ]

12. Sharman A, Furness P, Feehally J. Distinguishing C1q nephropathy from lupus nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2004;19:1420-6. [ Links ]

13. Fukuma Y, Hisano S, Segawa Y, Niimi K, Tsuru N, Kaku Y, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of C1q nephropathy in children. Am J Kidney Dis 2006;47(3):412-8. [ Links ]

14. Taggart L, Harris A, El-Dahr Samir. C1q nephropathy in a child presenting with recurrent gross hematuria. Pediatr Nephrol 2010;25:165-8. [ Links ]

15. Srivastava T, Chadha V, Taboada EM, Alon US. C1q nephropathy presenting as rapidly progressive crescentic glomerulonephritis. Pediatr Nephrol 2000;14(10-11):976-9. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Sofia Rocha,

Department of Nephrology,

Hospital de Santo António,

Centro Hospitalar do Porto,

Largo Professor Abel Salazar,

4099-001, Porto, Portugal

E-mail: sofiarocha81@gmail.com

E-mail: asgr_sigel@hotmail.com