My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Dynamis

On-line version ISSN 2340-7948Print version ISSN 0211-9536

Dynamis vol.34 n.2 Granada 2014

https://dx.doi.org/10.4321/S0211-95362014000200003

The physical activity of parturition in ancient Egypt: textual and epigraphical sources

Susanne Töpfer

Institute of Egyptology, University of Heidelberg.

toepfer@asia-europe.uni-heidelberg.de

ABSTRACT

Many medical and magical texts concerning childbirth and delivery are known from ancient Egypt. Most of them are spells, incantations, remedies and prescriptions for the woman in labour in order to accelerate the delivery or protect the unborn child and parturient. The medical and magical texts do not contain any descriptions of parturition itself, but there are some literary, astronomical and mythological texts, as well as a few incantations, which describe the biological act of childbirth and also miscarriage in more detail. Besides the textual sources, the decoration of temple walls and mammisis (birth houses), as well as illustrations on a birth brick provide an insight into the moment of delivery. In this paper, I focus on the "scientific" depiction of the biological act of childbirth, on how it is described in non-medical sources. Although the main sources are mythological-theological texts with numerous analogies, it is remarkable how many details they provide. They contain descriptions that would be expected in the context of medical sources.

Key words: miscarriage, umbilical cord, midwives, mammisi, birth brick.

Palabras clave: aborto espontáneo, cordón umbilical, parteras, casas de parto, ladrillo de parto.

1. Introduction

Gynaecological concepts including fertility and sexuality as well as childbirth and children's health are the topic in numerous sources from Pharaonic till Roman times (2nd millennium BC till the 3rd century AD). Most of them are medical and magical or rather medical-magical papyri1. The medical-magical manuscripts contain spells, incantations, remedies and prescriptions for women's and children's diseases -mainly of the womb, the vulva, the bladder and the stomach- for the woman in labour, to accelerate the delivery or to protect the unborn child and the parturient as well as prognoses about fertility, contraception and delivery. In general, the focus of these texts lies on the health and the protection of the prenatal, perinatal and postnatal woman and the unborn foetus, the newborn child or the infant. Remarkably, the medical texts do not contain any description of the parturition itself and as well there are no magical incantations and spells which have to be recited at the moment of delivery. The gynaecological texts do not deal with parturition, but only with the problems before and afterwards. It is astonishing that this fundamental activity is not being treated at any length in these texts since there is even a hieroglyph of a woman giving birth:  . On the basis of some literary, astronomical and mythological texts, however, we learn in more detail about the biological act of childbirth and also miscarriage and premature birth in Ancient Egypt. Although these sources contain numerous analogies and explain a divine birth, it is remarkable how many details they provide. Besides the textual sources, the decoration of temple walls and mammisis2 as well as the illustration on one single birth brick provide an insight into the moment of delivery.

. On the basis of some literary, astronomical and mythological texts, however, we learn in more detail about the biological act of childbirth and also miscarriage and premature birth in Ancient Egypt. Although these sources contain numerous analogies and explain a divine birth, it is remarkable how many details they provide. Besides the textual sources, the decoration of temple walls and mammisis2 as well as the illustration on one single birth brick provide an insight into the moment of delivery.

In this paper I want to focus on the physical act of childbirth and how it is described in non-medical sources. What can we find out about the obstetric position of the parturient and the posture of the midwives? In which way is the parturition described and displayed? Which terms are used? What can be said on the management of the afterbirth and the umbilical cord? Why do we have the physical description of childbirth in mythological and astronomical sources but not in medical texts?

2. Sources

The initial text for the research is from papyrus Westcar (around 1600 BC), which comprises five stories3. The fifth story is a prophecy of the birth of three kings. The description of the birth-scene is as follows (col. IX.21-X.13):

"One of these days it happened that Reddedet took sick and it was with difficulty that she gave birth. The Majesty of Ra (=the sun-god) (...) said to Isis, Nephthys, Meskhenet, Heket, and Khnum: May you proceed that you may deliver Reddedet of the three children who are in her womb (...) These goddesses proceed, and they transformed themselves into musicians, with Khnum accompanying them carrying the pack. When they reached the house of Rawosre, they found him standing with his apron untied (...) he said to them: My ladies, see, there is a woman in labor, and her bearing is difficult. They said to him: Let [us] see her, for we are knowledgeable about childbirth (...) Then they locked the room on her and on themselves. Isis placed herself in front of her, Nephthys behind her, and Heket hastened the childbirth. Isis then said: Do not be strong in her womb in this your name of Wosref. This child slipped forth upon her hands as a child one cubit long (...) They washed him after his umbilical cord had been cut, and he was placed upon a cushion on bricks. Then Meskhenet approached him, and she said: A king who will exercise the kingship in this entire land!"4

In this tale we are told three important things, on which I will focus in more detail: 1. the position of the divine midwives; 2. the acceleration of the childbirth; 3. the management of the newborn.

2.1.1. Temples and Birth-Houses

An interesting depiction of the first scene is a sequence of reliefs showing the myth of the birth of the god king in some temples of the New Kingdom (14th century BC)5 as well as at the mammisis of the temples of the Ptolemaic-Roman period (332 BC-1st century AD)6. The reliefs illustrate the procreation of the child by the god Amun and the queen, the creation of the child in the womb by the god Khnum, the childbirth as well as the aftercare and rendition of destiny to the godlike king.

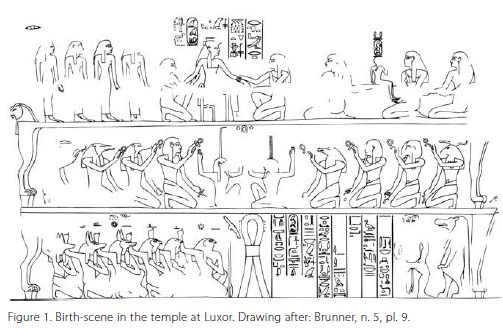

The birth-scene is nearly the same in the temples of the New Kingdom and the mammisis of the Ptolemaic-Roman period. In the version of the temple at Luxor (see figure 1), the parturient is sitting on a throne in the middle of the upper level of a bed, supported by two kneeling midwives behind and in front of her, surrounded by genii and apotropaic beings. Behind the two midwives are further supportive servants or midwives. Two cowering women on the right side hold the newborn child. The third cowering woman seems to be an intermediary between these two sequences: with the left hand she holds the infant and the lost right was possible stretched out to the kneeling midwife in front of her. Therefore, the topmost scene shows two stages of child-birth: the woman in labour at the moment of delivery (ejection phase), and the post-partum moment, in which the newborn child is in the hands of the nurses (afterbirth stage).

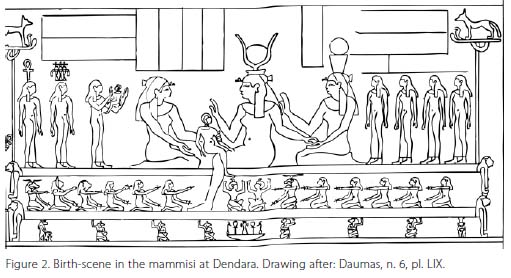

In other versions of the mammisis these two stages of child-birth are formalized in one single picture (see figure 2): the mother, again supported by two midwives, is holding the newborn child. The period during delivery and afterwards is combined in one image.

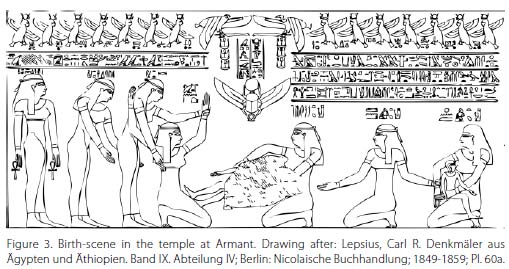

An identical scene is illustrated on a birth-brick from the late 13th Dynasty (1700-1650 BC) found at Abydos7. The posture of the midwives indicates that the scene on the side A shows not only the situation after delivery, where the mother holds the newborn for the first time, but also the exact moment of delivery8. However, the physical realism of the parturition, the suffering of the woman who needs help by the midwives -as the scene at Luxor suggests- is absent. An even more realistic depiction of the physical activity of parturition existed in the mammisi at Armant (around 50 BC), which was destroyed in the 19th century (see figure 3)9. The relief illustrates the birth of the divine child in the presence of gods: the parturient is kneeling on the earth; there is no bed or throne. Both her arms are raised and held by a woman standing behind her. Another woman standing behind the first one is also prepared to help. A kneeling woman in front of the parturient receives or perhaps pulls the child out of the womb. The energetic posture of her arms is noticeable. The woman behind the midwife acts as an intermediary between her and the second nurse, who is already suckling the child.

2.1.2. Astronomical and mythological texts

A proper description of the situation of the kneeling midwife with the child at Armant can be found in a handbook on Egyptian astronomy with religious-mythological background, the so-called "Book of Nut"10. There are nine documents of the text from the 13th century BC till the 2nd century AD In the earliest version on the ceiling of the "sarcophagus-chamber" at the temple Seti I at Abydos (the Osireion) it is written (col. 42):

"Then Isis and Nephthys stretched forth their hands towards Horus that they might receive him when Isis gave birth to him and he came forth from her womb"11.

The goddess Isis appears in a double role as mother of the child Horus and midwife together with her sister Nephthys. Isis and Nephthys in this astronomical context are probably acting as a kind of celestial midwives, who aid the moon or sun to rise in terms of a delivery12. For that purpose a passage from a hymn to the sun-god is of interest (text II 2, 14): "Isis and Nephthys lift you up when you come forth from the thighs of your mother Nut"13.

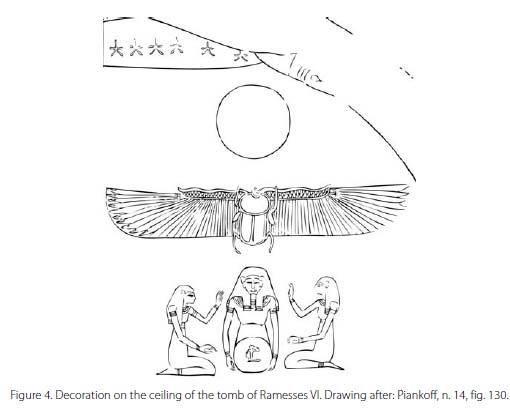

On a mythological-religious level the god Ra is born by his mother Nut, which means in an astronomical sense that the sun rises on the sky. An impressive image of this situation is the first scene of the so-called "Book of the Day" on the ceiling of the tomb of Ramesses VI, where the birth of the sun can be seen (see figure 4)14. The pregnant sky goddess is depicted with the sun-god as child in her womb or her amnion15, flanked by two women. These women are probably the goddesses Isis and Nephthys. The names and attributes are absent but certain illustrations of Isis and Nephthys raising the sun are shown beneath that scene and in another scene16.

The equation of the sunrise with human birth becomes apparent in another passage from the "Book of Nut":

"The majesty of this god goes forth from her hind part. He proceeds to the earth, risen and born (...) He opens the thighs of his mother Nut. He withdraws to the sky (...) He opens his amnion. He swims in his redness (...) The redness after birth"17.

It is obvious that the morning sunrise is described in biological terms. Notable is the description of Ra swimming in his redness, which means the sun disc at dawn. In the context of a biological birth this doubtless means the blood by which the child is covered together with embryonic connective tissue18.

Two further detailed descriptions of a biological birth can be found in another mythological handbook on papyrus. The papyrus Brooklyn 47.218.84 (7th century BC) contains myths of the delta regions19. The fifth myth of Bubastis is about the birth and doings of five forms of Horus. About one of them it is said (col. X.2-3):

"Concerning Hauron20: Osiris slept with his daughter Horit for her first time. She became pregnant, she sat down and was distressed. Then she arrived at the critical condition (or: the decision) to push off (or: give up) her

like that which was earlier done to Tefnut"21.

The episode is somewhat cryptic so it is not sure, whether it is a description of a normal birth or premature birth. The translation of the noun  is problematic but its context of birth is beyond doubt. Meeks pointed out that the word is a term for the egg and his annex that is the amnion fluid, the foetus and the afterbirth22. That is why Feder translated the word in the meaning of "amnion" 23. The noun

is problematic but its context of birth is beyond doubt. Meeks pointed out that the word is a term for the egg and his annex that is the amnion fluid, the foetus and the afterbirth22. That is why Feder translated the word in the meaning of "amnion" 23. The noun  is also mentioned in the next myth of Bubastis (col. XI.3-6):

is also mentioned in the next myth of Bubastis (col. XI.3-6):

"Then Seth harmed this goddess in Lower Imet. He raped her. She became pregnant with his semen (...) Then she arrived at the critical condition (or: the decision) that she would not complete her full term (of pregnancy). Her

was put in the water. The black Ibis found it in the water as baboon which had not yet been (fully) formed, amid the efflux (=amniotic fluid), which is his protection. (Because) he was in the womb of her

in her. He was not born like the (other) gods"24.

The translation of the term spr r j. .t is problematic. Feder's translation "she arrived at the decision" gives the impression that the goddess decides on her own to deliver. Considering the following condition of the newborn one could believe that the situation is an abortion. Meeks translates differently "she arrived at the critical condition", which means, that the time of pregnancy is finished and the child is ready to be delivered25. In his translation the myth seems to be a description of a premature birth and the baboon is an image of the foetus. There are some documents in which a premature birth or a miscarriage is mentioned. In the so-called "Oracular Amuletic Decree" Turin inv.-no. 1984 (early 19th century BC) the deities promise the bearer of the amulet the following (T. 2, rt. 112-115):

.t is problematic. Feder's translation "she arrived at the decision" gives the impression that the goddess decides on her own to deliver. Considering the following condition of the newborn one could believe that the situation is an abortion. Meeks translates differently "she arrived at the critical condition", which means, that the time of pregnancy is finished and the child is ready to be delivered25. In his translation the myth seems to be a description of a premature birth and the baboon is an image of the foetus. There are some documents in which a premature birth or a miscarriage is mentioned. In the so-called "Oracular Amuletic Decree" Turin inv.-no. 1984 (early 19th century BC) the deities promise the bearer of the amulet the following (T. 2, rt. 112-115):

"We shall (cause her) to conceive male children and female children. We shall keep her safe from a Horus-birth, from a irregular birth and from giving birth to twins"26.

Following Edwards, the expression "irregular birth" refers to a miscarriage or to a physical deformity of the child27. Furthermore, he points out that the fact that the woman is protected from a Horus-birth indicates an undesirable circumstance associated with giving birth28. Perhaps it refers to a premature birth, because according Plutarch's De Iside et Osiride the god Horus was prematurely born (chap. 65):

"For this reason it is said that Isis, when she was aware of her being pregnant, put on a protective amulet on the sixth day of Phaophi, and at the winter solstice gave birth to Harpocrates29, imperfect and prematurely born..."30.

To return to the myth of Bubastis, the not fully formed baboon is not only an image of the prematurely born foetus. Furthermore, the baboon -a manifestation of the god Thoth as is the black Ibis- is a term for the new moon31. Therefore, we have again the influence of a biological birth-metaphor on an astronomical phenomenon. In the passages of the astronomical handbook ("Book of Nut") as well as of the mythological handbook ("myths of the Delta") the birth of the sun and the moon, or rather the associated gods, is described in quite realistic biological terms. The physical activity of parturition becomes apparent.

2.1.3. Birth brick

To come full circle back to the tale of papyrus Westcar, in the as yet unpublished papyrus Berlin P. 15765a32 it is said about the birth brick and the umbilical cord (l. 1-3):

"as to this noble god when he was delivered upon his birth brick, his placenta came down and was put in the river (...) after his umbilical cord was cut off, the rope of his placenta, with a knife of reed33. It became (?) [...] [sn]ake in a moment of 170 cubits"34.

Following Quack, the text is a mythological narration about the birth of the sun god, who is the noble god, and the creation of his enemy, the snake Apophis, from his own umbilical cord35. What is remarkable is the explanation of the umbilical cord as "rope of his placenta". The placenta -the Egyptian term is mw.t-rm. which means literally "mother of humankind"36- is often mentioned in Egyptian texts of all categories, as is the umbilical cord; but neither the medical nor the magical or mythological sources contain such an anatomical description of the connection between the placenta and the umbilical cord. As in the before mentioned texts, the divine birth of the sun is explained in biological terms. In this passage it is noted that the delivery takes place on a birth brick. It is remarkable that there are in fact no images of a woman giving birth on a birth brick although it must have been common practice, considering the references in the numerous textual sources and the discovery of one exemplar37. To quote just one source: "I sat on the birth brick like the pregnant woman"38.

which means literally "mother of humankind"36- is often mentioned in Egyptian texts of all categories, as is the umbilical cord; but neither the medical nor the magical or mythological sources contain such an anatomical description of the connection between the placenta and the umbilical cord. As in the before mentioned texts, the divine birth of the sun is explained in biological terms. In this passage it is noted that the delivery takes place on a birth brick. It is remarkable that there are in fact no images of a woman giving birth on a birth brick although it must have been common practice, considering the references in the numerous textual sources and the discovery of one exemplar37. To quote just one source: "I sat on the birth brick like the pregnant woman"38.

Wegner and before him Roth and Roering assumed that the woman used four bricks39. That is why they translate the passage with the birth brick in the papyrus Westcar with "he was placed upon four bricks", proposing that the term jfd has to be translated as "four" rather than "cushion"40. The use of four bricks associated with four goddesses is known in textual sources of the Graeco-Roman period41. The handbook of materia sacra Berlin 7809/10+Louvre AF 11112 (Roman period) contains on fragment C a list of goddesses connected with terms of birth and destiny42. The Egyptian term for brick ms n.t43 is associated with four goddesses (frag. C, col. II, 5-7):

n.t43 is associated with four goddesses (frag. C, col. II, 5-7):

Following the assumption of four bricks, one could imagine the use of the bricks as shown in a drawing of piled birth bricks in modern Persia (see figure 5)45.

After the use of the bricks for the delivery they could be utilised as a support for the newborn on whom further magical and medical rites are performed, e.g. the clean separation of the umbilical cord. Like each activity before, during and after the delivery, this act needs magical protection, because the physical separation of mother and child by cutting the umbilical cord is an important step and perhaps dangerous in the Egyptian comprehension. Wegner suggests -based on textual and archaeological sources- a model of the physical practices associated with childbirth and the use of bricks46: At first the bricks have to be ritually prepared before they are used during the delivery, where the parturient stands upon the bricks, supported by two midwives, on both sides a Hathor-headed birth standard for magical protection, while a third woman protects the area of birth with a so-called "magical wand". After the delivery the bricks are used for the post-partum care and the protection of the new-born47.

Besides the sources which mention birth bricks we have to consider texts in which the position of the parturient is described differently. One relevant text is the yet unpublished papyrus Brooklyn 47.218.2 (7th century BC) a magical-medical papyrus with remedies, incantations and spells for the health and protection of mother and child before as well as after delivery48. Two spells for the protection of the bedchamber of the parturient in the birth-house (mammisi) are of concern. The first one (x+IV.7-8):

"Spell for the protection of the bedchamber (

nk.t)49 of the parturient: NN born of NN lies (

r) on a mat of reeds -another saying: a mat of alfa-grass- while Isis is at her womb, Nephthys is behind her, Hathor is beneath her head, Renenoutet is beneath her legs and Ipetweret makes her protection"50.

And the second (x+V.7-13):

"Spell for the protection of the bedchamber t s.t s

s.t s r s of the parturient (t

r s of the parturient (t ms.t): NN born of NN lies down while Isis is at her womb, Nephthys is behind her, Ipetweret is beneath her head, Renenoutet is beneath her legs and Ipetweret makes her protection. (...) To be pronounced over a drawing of Ipetweret51 at the top of the bed (

ms.t): NN born of NN lies down while Isis is at her womb, Nephthys is behind her, Ipetweret is beneath her head, Renenoutet is beneath her legs and Ipetweret makes her protection. (...) To be pronounced over a drawing of Ipetweret51 at the top of the bed ( .t n.t s

.t n.t s r)52, while Isis is at her right, Nephthys at her left and Rennenoutet beneath her legs"53.

r)52, while Isis is at her right, Nephthys at her left and Rennenoutet beneath her legs"53.

Following these spells, the parturient is lying on a mat or a bed, surrounded by divine midwives, among them again the main-midwives Isis and Nephthys in their usual positions. There is no mention of a birth brick, for which reason the moment of delivery does not necessarily involve a birth brick. But we have four goddesses on each side of the bed as we have four goddesses associated with the term for birth brick in the above mentioned handbook of materia sacra and there are four goddesses who accomplish the delivery of Reddedet in papyrus Westcar. Therefore, the four bricks are perhaps an allegory for the four divine midwives.

With this in mind, we still have the archaeological document of a birth brick as proof for their existence. Even if the birth brick, due to the good state of its preservation, may never have been actually used for a delivery, as Wegner assumed54. Perhaps the birth brick is to be understood as a "magically potent"55 object that was used at a delivery but without an active or rather physical use. The decoration of the birth brick is important for this aspect. The scenes on the edges of the brick consist of figures in human and animal form with apotropaic functions56. The scene on the main side57 displays a seated woman with a child in her arms, surrounded by two women, one standing behind her and another kneeling in front of her. The scene is framed by two wooden standards with a cow-head58. According to Wegner the decoration "should be understood to constitute a two-dimensional "visual spell" which invokes the presence of Hathor at the event of childbirth"59. The woman on the throne who is the parturient and at the same time the young mother is identified with the goddess Hathor. The two Hathor-headed tree emblems symbolise the horizon. Therefore the child is once more identified with the sun god Ra who rises on the horizon. The human birth equates with the birth of the sun: the mother=Hathor squats between the birth bricks=horizon=emblems and gives birth to the child=sun=Ra60. The "visual spell" may have been accompanied by further magical spells and invocations during delivery, e.g. spells to accelerate the childbirth.

2.2. Magical texts

The acceleration of the birth is the third important point in the initially mentioned passage from the papyrus Westcar. There is one magical papyrus with spells for the acceleration of birthgiving, which is exactly what the goddess Heket is doing in papyrus Westcar. The spells of papyrus Leiden I 348 (around 1200 BC) are magical remedies consisting of invocations and applications of amulets61. Some of them contain realistic descriptions of the birth activity and the situation of the woman in labour (spell 30, vs. XII.4-6):

"Come down, placenta, come down, placenta, come down! I am Horus who conjures in order that she who is occupied with birthgiving becomes better than she was, as if she were (already) delivered! ... To be recited four times over a dwarf of clay placed on the brow of a woman who is giving birth while suffering"62.

It is significant that the spell begins with the invocation of the placenta instead of the child. The birth of the child and the delivery of the placenta as after-birth seem to be the same activity. The childbirth is not finished until the delivery of the after-birth. On the other hand, I wonder if the spell may describe the after-birth contractions during the expulsion of the placenta. The expulsion of the placenta is the same activity as the delivery of the child and therefore also a birth. The dwarf-amulet of clay has the power to ease pain, no matter if the woman is delivering her child or "giving birth" to the placenta. The chronological order of the delivery of the child and afterwards the birth of the placenta is obvious in the already quoted mythological text of papyrus Berlin P. 15765a (l. 1-2):

"as to this noble god when he was delivered upon his birth brick, his placenta came down and was put in the river (...) after his umbilical cord was cut off, the rope of his placenta, with a knife of reed"63.

Another spell from the papyrus Leiden I 348 is for the acceleration of the birth for a woman who is overdue and is in great pain. The magician threatens the gods with natural disasters if they do not hurry to deliver the patient, who is identified with the goddess Isis (spell 34, vs. XI.4):

"Isis is suffering from her backpart being pregnant -but her month(s) have been completed, according to the (set) number in pregnancy- with her son, Horus"64.

In a further spell the situation of the husband and father-to-be is explained lifelike (spell 31, vs. XII.6-9):

"I am Horus! I had come down from the desert, being thirsty, on a shouting, <I> found somebody calling who stood weeping. His wife was nearing her time. I made the calling one stop weeping - the woman had shouted to the man for a dwarf-statue of clay (...) that she may cause to give birth the one who is to give birth"65.

The description is comparable with the condition of Rawosre in papyrus Westcar, who was standing in distress in front of his house with his apron untied and needed to be calmed down by the goddesses66.

3. Conclusion

To sum up, the textual and epigraphical sources never actually describe or depict a human birth. The royal birth described in papyrus Westcar and on the temple walls is always related to a divine birth, on the one hand by the identification of the mother with the goddesses Isis or Hathor, and on the other hand by the divine midwives. But in most of the sources the biological birth concept is connected to astronomical and cosmographical concepts. That conclusion is not unknown and an established motif in hymns to the sun since the 16th century BC67 The purpose of the illustration of the royal birth is the legitimization of the ruler. Therefore the realistic display is reserved and limited to what is necessary. In the mythological narrations on the contrary the divine birth is described realistically in biological terms as a human birth. Following Stricker, the macrocosmos "sun rise" and "divine birth" is compared with the microcosmos "childbirth" in mythological and astronomical handbooks68. In those scientific manuscripts69 childbirth is described in biological terms.

But why is the moment of parturition and physical activities linked to this never mentioned in medical texts, which would be considered to be scientific? A common explanation for a cultural scientist would be that it was taboo to speak of blood, amniotic fluid, embryonic connective tissue or cutting off the umbilical cord and delivering the afterbirth in a non-mythological context. But on the other hand, there are medical remedies for a prolapsed uterus or vaginal abscesses and magical spells against bleedings and miscarriages. Therefore, in my opinion, we should not assume a taboo. Rather, could it be possible that the Egyptians thought it would not be necessary to describe the physical act of childbirth in medical texts, since childbirth was not considered a disease for which a physician or magician was required. It is more likely that midwives accomplished the childbirth and they received the necessary knowledge by oral tradition. This is the reason why in the sources no god or male figure is present at the birth who could be interpreted as a divine physician or magician. One significance of this is the description of the god Khnum in the fifth story on papyrus Westcar as a luggage porter for the goddesses70. Only goddesses and divine midwives are present to help the woman in labour and to care for the newborn. Thus, childbirth is not a matter of healing it is a matter of helping.

References

1. There was no separation of medicine and magic in the Egyptian belief. With a separation in medical and magical texts I want to accentuate the key aspect of the text. In a "medical text" no apparent magical actions are performed or drugs with magical connotation are applied. In the opposite sense "magical texts" are spells or charms without explicit medication. On the topic: Ritner, Robert K. The mechanics of ancient Egyptian magical practice. Chicago: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago; 1993; [ Links ] Quack, Joachim F. Rezension zu Westendorf "Handbuch der altägyptischen Medizin". Orientalische Literaturzeitung. 1999; 94: 455-462; [ Links ] Schneider, Thomas. Die Waffe der Analogie. Altägyptische Magie als System. In: Gloy, Karen; Bachmann, Manuel, eds. Das Analogiedenken. Vorstöße in ein neues Gebiet der Rationalitätstheorie. Freiburg: Alber; 2000, p. 37-85; [ Links ] Fischer-Elfert, Hans-Werner. Altägyptische Zaubersprüche. Stuttgart: Reclam; 2005, p. 9-32. [ Links ] See also for Mesopotamian texts: Geller, Markham J. Ancient Babylonian Medicine. Theory and Practice. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010, p. 161-167. [ Links ]

2. An Egyptological term for a birth house inside a temple complex where the birth of the divine child was celebrated. On the term: Daumas, François. Les mammisis des temples égyptiens. Paris: Les Belles Lettres; 1958, p. 15-27; [ Links ] Kockelmann, Holger. Mammisi (Birth House). In: Wendrich, Willeke, ed. UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. Los Angeles; 2011. Available from: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/8xj4k0ww (accessed 30 Nov 2012). [ Links ]

3. Berlin, Ägyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung, inv.-no. P. 3033. For the edition of the manuscript see: Blackmann, Aylward M. The Story of King Kheops and the magicans. Reading: JV Books; 1988; [ Links ] Lepper, Verena. Untersuchungen zu pWestcar. Eine philologische und literaturwissenschaftliche (Neu-) Analyse. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz; 2008. [ Links ] On the problematic of the dating of the text: Burkhard, Günther; Thissen, Heinz J. Einführung in die Altägyptische Literaturgeschichte. Altes und Mittleres Reich. Münster: Lit; 2003, p. 178-180. [ Links ]

4. Translation after: Simpson, William Kelly. King Cheops and the magicians. In: Simpson, William Kelly, ed. The literature of ancient Egypt. An anthology of stories, instructions, stelae, autobiographies and poetry. New Haven: Yale University Press; 2003, p. 21-22. [ Links ] The description of the birth is the same for the two other kings.

5. Brunner, Helmut. Die Geburt des Gottkönigs. Studien zur Überlieferung eines altägyptischen Mythos. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz; 1986. [ Links ] For the evidence of the birth myth in the Middle and maybe the Old Kingdom see: Oppenheim, Adela. The early life of Pharaoh: Divine birth and adolescence scenes in the causeway of Senwostret III at Dahshur. In: Bárta, Miroslav; Coppens, Filip; Krejčkí, Jaromír, eds. Abusir and Saqqara in the year 2010/1, Prague: Charles University in Prague; 2011, p. 171-188. [ Links ]

6. Daumas, François. Les mammisis de Dendara. Cairo: L'Institut Français d'Archeologie Orientale; 1959. [ Links ]

7. Published by: Wegner, Josef. A decorated birth-brick from South Abydos. In: Silverman, David; Simpson, William Kelly; Wegner, Josef, eds. Archaism and innovation. Studies in the Culture of Middle Kingdom Egypt. New Haven: Yale University Press; 2009, p. 447-496. [ Links ]

8. Wegner, n. 7, p. 451, fig. 3-4.

9. Arnold, Dieter. Zum Geburtshaus von Armant. In: Guksch, Heike; Polz, Daniel, eds. Stationen. Beiträge zur Kulturgeschichte Ägyptens. Mainz: Phillip von Zabern; 1998, p. 427-432; [ Links ] Ray, John. Cleopatra in the temples of upper Egypt: The evidence of Dendera and Armant. In: Walker, Susan; Ashton, Sally-Ann, eds. Cleopatra reassessed. The British Museum Occasional Paper No. 103. London: British Museum; 2003, p. 9-11. [ Links ] Budde, Dagmar. Harpare-pa-chered. Ein ägyptisches Götterkind im Theben der Spätzeit und griechisch-römischen Epoche. In: Budde, Dagmar; Sandri, Sandra; Verhoeven, Ursula, eds. Kindgötter im Ägypten der griechisch-römischen Zeit. Leuven: Peeters; 2003, p. 47-50. [ Links ]

10. Neugebauer, Otto; Parker, Richard A. Egyptian astronomical texts I. The early decans. London: Lund Humphries; 1960, p. 36-87; pl. 30-33, 44-54; [ Links ] von Lieven, Alexandra. Grundriss des Laufes der Sterne. Das sogenannte Nutbuch. CNI Publications 31. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press; 2007. [ Links ]

11. Translation: De Buck, Adrian. The dramatic text. In: Frankfort, Henri. The Cenotaph of Seti I at Abydos. London: Offices of the Egypt Exploration Society; 1933, p. 86. [ Links ] See also: von Lieven, n. 10, p. 110 (§x+98).

12. von Lieven, n. 10, p. 195.

13. Translation after: Assmann, Jan. Liturgische Lieder an den Sonnengott. Berlin: Hessling; 1969, p. 188. [ Links ]

14. Piankoff, Alexandre. The tomb of Ramesses VI. New York: Pantheon Books; 1954, p. 389-407; [ Links ] fig. 130; pl. 187; Müller-Roth, Marcus. Das Buch vom Tage. Fribourg: Academic Press; 2008. [ Links ]

15. For the interpretation of that scene: Quack, Joachim F. Review of Dorman, Faces in Clay. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft. 2005; 155: 611; [ Links ] Müller-Roth, n. 14, p. 467.

16. Müller-Roth, n. 14, p. 70-77; 465-470.

17. Translation after: von Lieven, n. 10, p. 51-54. Furthermore: Neugebauer; Parker, n. 10, p. 48-49, 81.

18. von Lieven, n. 10, p. 133.

19. Text edited by Meeks, Dimitri. Mythes et légendes du Delta d'apres le papyrus Brooklyn 47.218.84; Cairo: Inst. Français d'Archéologie Orientale; 2006. [ Links ] German translation: Feder, Frank. Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae. Available from http://aaew.bbaw.de/tla/ (updated 31 Oct 2012; accessed 30 Nov 2012). [ Links ]

20. Reading "Hauron" following Quack, Joachim F. Review of Meeks, Mythes et Légendes du Delta d'apres le papyrus Brooklyn 47.218.84. Orientalia. 2008; 77: 109. [ Links ] Meeks, n. 19, p. 22 and Feder, n. 19 read "Houmehen".

21. Translation after: Meeks, n. 19, p. 22. Translation in brackets after: Feder, n. 19. See also Jørgensen, Jens. Myths, menarche and the return of the Goddess. In: Nyord, Rune; Ryholt, Kim, eds. Lotus and Laurel: Studies on Egyptian language and religion in honour of Paul John Frandsen. CNI Publications 39. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press; in press. [ Links ] Jorgensen, Jens. Egyptian Mythological Manuals. Mythological structures and interpretative techniques in the tebtunis Mythological manual, the Manual of the Delta and related texts; unpubl. Dissertation: Copenhagen; 2013; 134-139. [ Links ] I want to thank Jens Jorgensen for sending me his article before publishing and his yet unpublished dissertation script. I am also gratful for the opportunity to discuss the material with him.

22. Meeks, n. 19, p. 108 (com. 316). For a semantic analysis of the word: Jørgensen, n. 21.

23. Feder, n. 19.

24. Translation after: Meeks, n. 19, p. 24. Translation in brackets after: Feder, n. 18. See also: Jørgensen, n. 21.

25. Meeks, n. 19, p. 107 (com. 315).

26. Translation: Edwards, Iorwerth E. Hieratic papyri in the British Museum Ser. 4. Oracular Amuletic decrees of the late new kingdom. London: British Museum Press; 1960, p. 66, pl. XXIV. [ Links ]

27. Edwards, n. 26, p. 66 (note 68).

28. Edwards, n. 26, p. 66 (note 67).

29. Greek for "Horus, the child".

30. Translation: Griffiths, John G. Plutarch's De Iside et Osiride. Cardiff: University of Wales Press; 1970, p. 221, 530. [ Links ]

31. Meeks, n. 19, p. 115 (com. 361), 258-260.

32. The papyrus is edited by Quack, Joachim F. Die Geburt eines Gottes?, in preparation. I want to thank him to allow me to use his unpublished manuscript. So far: Quack, Joachim F. Apopis, Nabelschnur des Re. Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur. 2006; 34: 377. [ Links ]

33. The use of reed to cut the umbilical cord is documented in babylonian and assyrian sources; see Volk, Konrad. Vom Dunkel in die Helligkeit. Schwangerschaft, Geburt und frühe Kindheit in Babylonien and Assyrien. In: Dasen, Véronique, ed. Naissance et petite enfance dans l'Antiquité. Actes du colloque de Fribourg, 28 novembre-1er décembre 2001. Fribourg: Academic Press; 2004, p. 85-86. [ Links ]

34. Translation after: Quack, n. 32.

35. Quack, n. 32.

36. von Deines, Hilde. Mutter der Menschen. Mitteilungen des Instituts für Orientforschung. 1954; 4: 27-39. [ Links ]

37. However, the practice of bricks at the birth is documented for Mesopotamia: Wegner, n. 7, p. 472; 475-477. On the textual sources for the use in Ancient Egypt, see Roth, Ann Macy; Roehrig, Catharine H. Magical Bricks and the Bricks of Birth, In: The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 2002; 88: p. 129-139. [ Links ]

38. Stele Turin 50058: Tosi, Mario; Roccati, Alessandro. Stele e altre epigrafi di Deir el Medina. Turin: Pozzo; 1972, p. 94-96. [ Links ] Translation after: Adrom, Faried. "Der Gipfel der Frömmigkeit". Soziale und funktionale Überlegungen zu Kultstelen am Beispiel der Stele Turin 50058 des Nfr-obw. Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur. 2005; 33: 22. [ Links ]

39. Wegner, n. 7, p. 472; 477-478; Roth; Roehrig, n. 37, p. 131-132.

40. For the discussion of the term: Staehelin, Elisabeth. Bindung und Entbindung. Erwägungen zu Papyrus Westcar 10, 2. Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde. 1970; 96: 130. [ Links ]

41. Derchain-Urtel, Maria-Theresia. Synkretismus in ägyptischer Ikonographie. Die Göttin Tjenenet. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz; 1979, p. 23-34; [ Links ] Raven, Maarten. Egyptian Concepts on the Orientation of Human Body. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 2005, 91: 50-52. [ Links ]

42. Text edited by Osing, Jürgen. Hieratische Papyri aus Tebtunis I. CNI Publications 17. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press; 1998, p. 276-296, pl. 29-30. [ Links ]

43. On the term: Wegner, n. 7, p. 471-480 with further references.

44. Translation after: Osing, n. 42, p. 285.

45. Wegner, n. 7, p. 476-477, fig. 14.

46. Wegner, n. 7, p. 481, fig. 15.

47. Wegner, n. 7, p. 480-485.

48. The publication of the papyrus is in preparation by Ivan Guermeur (Montpellier) in collaboration with Paul O'Rourke (Brooklyn). I want to thank Ivan Guermeur for allowing me to use his translation of the text. A first description of the papyrus and some spells: Guermeur, Ivan. À propos d'un passage du papyrus medico-magique de Brooklyn 47.218.2 (x+III.9-x+IV.2). In: Zivie-Coche, Christiane; Guermeur, Ivan, eds. "Parcourir L'Éternité" Hommages à Jean Yoyotte Vol. I. Turnhout: Brepols; 2012; p. 541-555. [ Links ]

49. Following the Wörterbuch der Ägyptischen Sprache Vol. III, p. 119.8-13 the term hnk. [ Links ]t characterized a room in the temple, the house and the palace. The translation "bedchamber" follows from the love poems of Papyrus Harris 500, rt. V.7 and VII.12. The use of the term in this context is the evidence that in Ancient Egypt the childbirth did not take place on the roof of the house or outside in a so-called "Wochenlaube", as some scholars supposed (Brunner-Traut, Emma. Die Wochenlaube. Mitteilungen des Instituts für Orientforschung; 1955; 3: 11-30), [ Links ] but inside the house or the birth-house. Further evidence is the passage in the Papyrus Westcar in which the goddesses locked the room in the house of Rawoser. For the term s3-hnk.t "protection of the bedchamber" see with further references: Pries, Andreas H. Das nächtliche Stundenritual zum Schutz des Königs und verwandte Kompositionen. Der Papyrus Kairo 58027 und die Textvarianten in den Geburtshäusern von Dendara und Edfu. Studien zur Archäologie und Geschichte Altägyptens; 2009; 27: 98-99. [ Links ]

50. Translation after: Guermeur, n. 48, in preparation.

51. Ipetweret is the goddess of fertility and childbirth and the image of her is a magical protection for the parturient.

52. 3t.t is a term for "bed" or "bier" (Wörterbuch der Ägyptischen Sprache Vol. I, p. 23.11-12). The use in the context of childbirth is to emphasize since the root of the word is 3ti "to bring up (a child)" or "to rear (a child)". The noun 3t.yt "nurse; attendant" derives also from the verb 3ti. Therefore the term 3t.t perhaps describes a special delivery table.

53. Translation after: Guermeur, n. 48, in preparation.

54. Wegner, n. 7, p. 475-477.

55. Wegner, n. 7, p. 458.

56. Wegner, n. 7, p. 452-455, fig. 6.

57. This is the lower face. According to the orientation of the edge scenes the destroyed upper face was the brick's primary surface. See: Wegner, n. 7, p. 449, fig. 1.

58. Description: Wegner, n. 7, p. 449-455.

59. Wegner, n. 7, p. 458.

60. Wegner, n. 7, p. 463.

61. Text edited by Borghouts, Joris F. The magical texts of Papyrus Leiden I 348. Oudheidkundige Mededelingen Rijksmuseum Oudheiden. Leiden. 1971; 51: 1-248. [ Links ]

62. Translation: Borghouts, n. 61, p. 29.

63. Translation after: Quack, n. 32.

64. Translation: Borghouts, n. 61, p. 30-31.

65. Translation: Borghouts, n. 61, p. 29.

66. Borghouts, n. 61, p. 29.

67. Müller-Roth, n. 14, p. 467-468 with further references.

68. Stricker, Bruno H. De Geboorte van Horus Vol. IV. Leiden: Brill; 1982, p. 349-368. [ Links ]

69. On the definition of Egyptian scientific text: Quack, Joachim F. Präzision in der Prognose oder: Divination als Wissenschaft. In: Imhausen, Annette; Pommerening, Tanja, eds. Writings of early scholars in the Ancient Near East, Egypt, Rome, and Greece. Berlin: de Gruyter; 2010; p. 69-70. [ Links ]

70. I would like to thank Friedhelm Hoffmann (München) for that note.

Fecha de recepción: 4 de diciembre de 2012

Fecha de aceptación: 4 de febrero de 2014