Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO  Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Nutrición Hospitalaria

versión On-line ISSN 1699-5198versión impresa ISSN 0212-1611

Nutr. Hosp. vol.19 no.1 Madrid ene./feb. 2004

Original

Peripheral parenteral nutrition: an option for patients with an indication for short-term parenteral nutrition

M. I. T. D. Correia, MD, PhD, J. Guimarâes, L. Cirino de Mattos, K. C. Araújo Gurgel y E. B. Cabral

Department of Surgery, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Brazil

| Abstract Objective: The aim of this study was to examine and describe our experience with the use of peripheral parenteral nutrition (PPN). (Nutr Hosp 2004, 19:14-18) Keywords: Complications. Peripheral parenteral nutrition. | LA NUTRICIÓN PARENTERAL PERIFÉRICA, ALTERNATIVA PARA LOS PACIENTES CON INDICACIÓN DE NUTRICIÓN PARENTERAL DURANTE POCO TIEMPO Resumen Objetivo: El objetivo de este estudio consiste en examinar y describir nuestra experiencia con la nutrición parenteral periférica (NPP). (Nutr Hosp 2004, 19: 14-18) Palabras clave: Complicaciones. Nutrición parenteral periférica. |

Corresponding author: M. I. T. D. Correia.

Rua Gonçalves Dias 332/602.

Belo Horizonte, MG, 30140-090.

Telefone: 319 983 72 28; fax: 313 222 29 32

E-mail: Isabel_correia@uol.com.br

icorreia@medicina.ufmg.br

Recibido: 8-V-2003.

Aceptado: 12-VI-2003.

Introduction

Parenteral nutrition (PN) has traditionally been delivered via a central vein, most frequently the subclavian or the jugular vein1. This is because parenteral nutrition, a high osmolality solution, can cause thrombophlebitis in smaller vessels, which increases morbidity and mortality2. On the other hand, percutaneous access of a central vein involves higher risks of complications, such as pneumothorax, hemothorax, brachial nerve injury, gas embolism, among others2, 3. Maintenance of a central venous catheter is also a risk factor that contributes to infectious complications. Of these, sepsis is the most worrisome, because it represents significantly increased morbidity and mortality with concomitant increased costs1-4. Beyond this, the broader indications for enteral nutrition and the great variety of available formulas have significantly decreased the number of patients, who in the past would receive PN5, 6. Nonetheless, for those patients who present with a partially or totally non-functional gastrointestinal tract, the indication for PN is fundamental, especially if they are undernourished or should undergo a period of prolonged fasting7, 8. Therefore, parenteral nutrition delivered in a peripheral vein has become an attractive option for those in need of this type of therapy for a short period of time (less than 15 days).

Peripheral parenteral nutrition (PPN) has been associated with increased thrombophlebitic episodes, although the latter represent lesser risks for severe infectious complications than the ones related to central parenteral nutrition and when strict protocols are followed does not impose greater morbidity.

The aim of this study was to examine and describe the experience of our nutrition therapy team with the use of peripheral parenteral nutrition.

Methods

Patients with an indication for parenteral nutrition for an estimated time less than 15 days received PN via a peripheral vein cannulated with short, 20 or 22 gauge French polyurethane catheters. The following criteria for venous access puncture and maintenance were followed: large veins in the upper extremities, starting from the most distal to the proximal veins. When the venous access was lost, a vein in the contralateral extremity was used; the veins were also used for intravenous fluids and drugs, and therefore were not exclusive for PN, although while infusing drugs, PN was interrupted; antisepsis of the site was performed with PVPI solution. The accesses were puncture by nurses, previously trained by the nutrition team to follow the study protocol, which requires dry dressings fixed with anti-allergic tape.

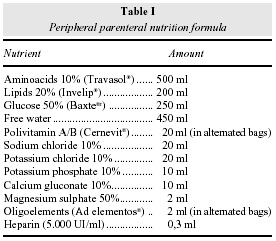

The prescribed parenteral solution formula had a final osmolality of 993 mOsm/l and is shown in table I. The formula was prepared in an industrial pharmacy with all the nutrients added in 2000 ml ethilvinilacetate (EVA) bags (Baxter laboratories®), according to the Brazilian Health Department rules disposed in amend number 272 of the Health Surveillance Department9. PPN was administered by a pump in a continuous infusion mode, 24 hours a day.

All the patients were nutritionally assessed by the Subjective Global Assessment (SGA) technique. Nutritional requirements were calculated based on the actual body weight, with the exception of the obese patients in whom the ideal body weight was used based on a body mass index of 25 kg/m2. The caloric requirements were calculated by the quick formula of 25 kcal/kg to 30 kcal/kg day and proteins were given as 1.2 to 1.5 g/kg/day. Previous to beginning PPN, blood samples were obtained for routine tests established in our parenteral nutrition protocol (table II).

The nutrition therapy team followed the patients on a daily basis, respecting all the existing protocols for patients on parenteral nutrition. These include: capillary glucose (at least, every twelve hours); blood electrolyte, renal and hepatic function tests every 72 hours or less, according to individual cases and albumin, triglyceride and cholesterol samples, every seven days or less, if necessary. The venipuncture site was assessed daily for: 1 – spontaneous patient referred pain; 2 – pain and hyperthermia; 3 – pain, hyperthermia and edema; 4 – local abscess. If any of these symptoms or signs were present, the venipuncture site was changed. In no patient was the site changed as a routine procedure, in the absence of local alterations.

The duration of each vein access was compared using the Kruskall Wallis statistical test and a p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Fifty-three patients were followed and the mean age was 59.5 ± 17.5 years. There were 36 males (69.2%). Nutritional assessment showed severe malnutrition in 53.8% of the patients, 38.5% were moderately malnourished or presented with suspected malnutrition and 7.7% were well nourished. The PPN indications are shown in table III. The average caloric requirements were 1,556 + 251 kcal (1,000 – 2,000 kal) and the protein need 60.0 ± 16.6 g (44 - 99 g). Nutritional requirements were reached in 67.6% of the patients within 2.9 ± 0.7 days (2 - 4 days) after the beginning of the infusion. The mean time on parenteral nutrition was 7.2 ± 6.6 days (1 a 33 days). The first venous access lasted an average of 3.3 ± 2.2 days. Thirty-five patients (66.0%) received PPN for less than seven days. They were classified as group one. In this group, five patients (14.2%) required three venous accesses, 48.5% required two veins and 13 patients (37.4%) required one venous access. In 74.3% of the cases parenteral nutrition was offered until the end of the planned treatment. Seven patients died (11.4%) and three (8.6%) required central venous lines. In two patients (5.7%) PPN was suspended due to unsuccessful cannulation of the peripheral veins (these patients were already receiving enteral nutrition). Accidental loss of the venous access was the main cause for a new vein cannulation in 45.8% of the patients. Pain occurred in 17.1% of the cases, pain and fever in 20% and pain, hyperthermia and edema in 2.8%. No patient developed an abscess.

The factor that led to the changing of the venous access in those patients on PPN for longer than seven days (group two – 18 patients) was accidental loss of venous access in 48.3%. One patient developed an abscess in the venipuncture site, in his third vein access.

There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of factors influencing the changing of the venous access and the time duration of each one of them.

The use of PPN did not cause any metabolic alteration such as increased hepatic enzymes, renal function and cholesterol and triglyceride values. No patient presented with blood glucose above 220 mg/dl.

Discussion

The prevalence of malnutrition in the hospital, at the beginning of the new millennium, is still highly prevalent. In Brazil, the IBRANUTRI study showed that 48.1% of the hospitalized patients were malnourished, with 12.6% being severely malnourished10. Malnutrition is related to increased morbidity, length of hospital stay, costs and mortality11. Therefore, many of these patients are potentially benefited by the use of nutritional therapy, which when started early might contribute to improving the nutritional status1. Preferentially and whenever possible, the best artificial nutrition route is the enteral one because it is more physiological, is associated with less morbidity and mortality and is less expensive5. However, some patients, mainly those with gastrointestinal obstruction, with prolonged paralytic ileus, no enteral access or severe malnutrition, would certainly be benefited with parenteral nutrition. In these situations, the most common duration of PN is less than 15 days, which then justifies its administration by the peripheral route. A study done in the United Kingdom, in 1988, showed that although PN was used by only 7% of the physicians who replied to the survey, 84% of the central parenteral nutrition were used for a period less than 14 days and 27% for less than seven days12. Another study showed that 83% of the prescribed parenteral nutrition was administered for an average period of less than 10 days13. The group of Payne-James et al repeated the previous parenteral nutrition survey in 1991, and they found that peripheral parenteral nutrition was offered in 15% of the centers and in some of them up to 58% of the parenteral nutrition administrations were offered by the peripheral route14. In our hospital 60% of the parenteral nutrition is administered by the peripheral route because as we have demonstrated in this study, the great majority of the patients were postoperative for laparotomies for treatment of gastrointestinal or bladder cancer. The prevalence of malnutrition in this group of patients was extremely high (92.3%) with 39.6% being severely malnourished. The explanation for such a high rate of malnutrition is that our hospital is a referral cancer center that receives patients with low socioeconomic status coming from all over the state. Only five patients did not present with cancer.

A few years ago the use of PPN was questioned because it was thought that through this route it was not possible to provide the patients nutritional requirements1. However, today, it is well known that the great majority of patients demand only an average of 1500 to 2000 kcal, which represents between 25 to 30 kcal/kg/day15, 16, and 1.2 to 2.0 g/kg/day of proteins17. We have shown that the nutritional requirements of our patients was 1500 ± 251 kcal/day and 67.0 ± 15.6 g of proteins/ day. Therefore the parenteral nutrition administered to them was complete in terms of macro and micro nutritional requirements and 67.7% of the patients received it within 2.9 ± 0.7 days. There were some patients who did not meet their nutritional requirements with the PPN because they also received enteral nutrition and with tolerance to this, PPN was discontinued.

The osmolality of the solution used in our service is 993 mOsm/l, which is considered by some authors as being well tolerated by the peripheral route18. Other authors are totally against the use of formulas with osmolalities above 800 mOsm/l19. The high osmolality solutions increases the risk of thrombophlebitis1, 18, 19. However, by using preventive attitudes, the severity of the vascular lesion might be minimized taking into consideration the risk factors associated with the development of thrombophlebitis which are: bacterial colonization at the venipuncture site; catheter size and material; duration of infusion; cyclic versus continuous; trauma at the moment of the venipuncture and vein size, among others1. Dinley showed that polyvinyl chloride catheters were highly related to thrombophlebitis episodes when compared to silicone catheters20. It seems that polyurethane catheters are the best, since these have a wider internal lumen while keeping the same external diameter, they are more resistant and like the silicone catheters are less thrombogenic, since platelet aggregation seems to be reduced21. In our service, the routine is to use short polyurethane catheters, not wider than 20 French bore and whenever possible placed in larger veins. Lately, we have chosen to use 22 French catheters. Local antisepsis is performed with PVPI and nursing staff training and recycling has been carried out every six months to guarantee the control over venous cannulation among other activities. Heparin (one unit per milliliter) in the parenteral solution is also routinely used by our team. This dose is low and seems to decrease the possibility of fibrin clotting around the catheter. The clotting usually occurs right after the venous puncture and seems to be minimized by the use of heparin. Fibrin deposition is the cause of thrombus formation and occlusion, which therefore leads to the thrombophlebitis phenomenon. Several studies have demonstrated that the addition of heparin (1 U/ml) decreases the risk of thrombophlebitis and increases the integrity of the veins from 26.1 hours to 58.7 hours (mean time)22. We observed that the mean venous access duration was 3.3 ± 2.2 days (1 to 14 days) for the first venous access, 2.2 ± 1.1 days ( 1 - 6 days) for the second, 2.4 ± 1.6 for the third (1 - 6 days) and 2.2 ± 2.1 for the fourth. Theses differences were not statistically different and are in accordance with other experiences23. It was always our option to perform the changing of the puncture site whenever there was any sign of venous lesion.

The use of lipids in a 3:1 solution is encouraged, since they represent a further protection to the venous endothelium24, besides contributing as a caloric load to reach the nutritional requirements. The 20% lipid solution is preferred because it provides double calories in a smaller volume.

Other prophylactic attitudes such as the addition of corticosteroids to the parenteral solution, the use of glycerol and buffering the solution with sodium bicarbonate have been mentioned in the literature as measures to avoid thrombophlebitis1, 25. Topical use, at the venipuncture site, of trinitrate glyceril and anti-inflammatory drugs has been suggested1, 25. However, in our protocol none of these measures was used, since we believe that extra variables might increase the risk of complications associated with them. Its been our impression that the use of parenteral nutrition, the adequacy of the nutritional requirements, the strict protocols on venous access and follow-up, the addition of heparin and lipids, as well as the existence of a nutritional support team, has offered good results. However, we unfortunately have faced the accidental loss of a great number of venous access sites. The latter probably is due to the lack of care in adequately fixing the catheters, lack of patient orientation and especially lack of an appropriate mobile hanging apparatus that make patient ambulation easier and safer.

The presence of a nutritional support team is a well-defined factor that helps prevent complications and reduces costs25. Tombord et al26 compared the results of 863 peripheral catheters controlled by a nutritional support team with other catheters controlled by the nursing staff. Those catheters followed by the team had an incidence of thrombophlebitis of 15% while the others 32%. Moreover, serious complications were decreased from 2.1% to 0.2%.

In summary, in our experience the use of PPN can benefit a great number of patients who are in need of parenteral nutrition, without the risks linked to a venous central catheter. Complications associated with PPN are low especially when strict protocols on indications, care and follow-up are adopted. We consider the existence of a nutrition support team an important requirement.

References

1. Payne-James JJ and Khawaja HT: First choice for total parenteral nutrition: the peripheral route. J Parent Ent Nutrition, 1993, 17:468. [ Links ]

2. Wolfe BM, Ryder MA, Nishikawa RA, Halsted CH and Schmidt BF: Complications of parenteral nutrition. Am J Surg, 1986, 152:93. [ Links ]

3. Mughal MM: Complications of intravenous feeding catheters. Ann Surg, 1985, 202:766. [ Links ]

4. Pettigrew RA, Lang SDR, Haydock DA, Parry BR, Bremner DA and Hill GL: Catheter-related sepsis in patients on intravenous nutrition: a prospective study of quantitative catheter cultures and guidewire changes for suspected sepsis. Br J Surg, 1985, 72:52. [ Links ]

5. Murray MJ: Confusion reigns: enteral versus total parenteral nutrition. Crit Care Med, 2001; 29:446. [ Links ]

6. MacFie J: Enteral versus parenteral nutrition. Br J Surg 2000; 87:1121. [ Links ]

7. Hill AD and Daly JM: Current indications for intravenous nutritional support in oncology patients. Surg Oncol Clin N Am, 1995, 4:549. [ Links ]

8. Satyanarayana R and Klein S: Clinical efficacy of perioperative nutrition support. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care, 1998, 1:51. [ Links ]

9. Brasil. Secretaria de Vigilância Sanitária. Ministério da Saúde. Portaria no 272, de 8 de abril de 1998. diário Oficial da União, 9 de abril de 1998. [ Links ]

10. Detsky AS, McLaughlin JR, Baker JP et al: What is subjective global assessment of nutritional status? JPEN, 1987, 11:8. [ Links ]

10. Waitzberg DL, Caiaffa WT and Correia MITD: Hospital malnutrition: The Brazilian National Survey (IBRANUTRI): a study of 4000 patients. Nutrition, 2001, 17:573. [ Links ]

11. Correia MITD: Repercussôes da desnutriçâo sobre a morbimortalidade e custos em pacientes hospitalizados no Brasil [tese]. Sâo Paulo: USP, 2000. [ Links ]

12. Payne-James JJ, de Gara CJ and Grimble GK: Nutritional support in hospitals in the Unidted Kingdom: National survey 1988. Health Trends, 1990, 22:9. [ Links ]

13. Khawasja HT, Williams JD and Weaver PC: Transdermal glyceryl trinitrate to allow peripheral total parenteral nutrition: a double blind placebo controlled feasibility study. J R Soc Med, 1991, 84:69. [ Links ]

14. Payne-James JJ, de Gara CJ and Grimble GK: Artificial nutrition support in hospitals in the United Kingdom - 1991: second national survey. Clin Nutr 1992, 11:187. [ Links ]

15. MacFie J: Active metabolic expenditure of gastroenterological surgical patients receiving intravenous nutrition. J Parent Ent Nutr, 1984, 8:371. [ Links ]

16. Weissman C, Kemper M, Asklanai J, Hyman AI and Kinney JM: Resting metabolic rate of the critically ill patient: measured versus predicted. Anesthesiology, 1986, 64:673. [ Links ]

17. Ishibashi N, Plank LD, Sando K and Hill GL: Optimal protein requirements during the first 2 weeks after the onset of critical illness. Crit Care Med, 1998, 26:1529. [ Links ]

18. Kane KF, Colgiovanni L, McKiernam J, Panos MZ, Ayres RCS, Langaman MJS et al: High osmolality feeding do not increase the incidence of thrombophlebitis during peripheral IV nutrition. J Parent Ent Nutri, 1996, 20:194. [ Links ]

19. Blackburn GL, Flatt JP and Clowes GHA: Peripheral intravenous feeding with isotonic amino acid solutions. Am J Surg, 1973, 125:447. [ Links ]

20. Dinley RJ: Venous reactions related to indwelling platic cannulae: a prospective clinical trial. Curr Med Res Opin, 1976, 3:607. [ Links ]

21. Dábrera VC, Elliott TSJ and Parker GA: The ultrastructure of intravascular devices made from a new family of poyurethanes. Intensive Ther Clin Monitor, 1988, 12:8. [ Links ]

22. Tanner WA, Delaneyu PV and Hennessy TP: The influence of heparin on intravenous infusions: a prospective study. Br J Surg, 1980, 67:311. [ Links ]

23. Alpan G, Eyal F, Springer C, Glick B, Goder K and Armon J: Heparinization of alimentation solutions administered through peripheral veins in premature infants: a controlled study. Pediatrics, 1984, 74:375. [ Links ]

24. Fujiwara T, Kawarasaki H and Fonkalsrud EW: Reduction of post infusion venous endothelial injury with Intralipid. Surg Gynecol Obstet, 1984, 158:57. [ Links ]

25. Culebras JM, García de Lorenzo A, Zarazaga A and Jorquera F: Peripheral parenteral nutrition. In: John L, Rombeau, Rolando H, Rolandelli: Parenteral Nutrition, 3rd ed. New York: WB Saunders company, 2000: 580-587. [ Links ]

26. Tomford JW, Hershey CO, McClaren CE, Porter DK and Cohen DI: Intravenous therapy team and peripheral venous catheter-associated complications: a prospective controlled study. Arch Intern Med, 1984, 144:1191. [ Links ]