INTRODUCTION

Depression refers to a wide range of mental health problems characterized by the absence of positive affect (a loss of interest and enjoyment in ordinary things and experiences), persistent low mood, and a range of associated emotional, cognitive, physical, and behavioral symptoms (1). Affecting more than 264 million people worldwide (2), depression is a leading cause of disease burden and a major contributor to global disability (3). It has been estimated that current treatments reduce only about one-third of the disease burden associated with major depressive disorder (4). However, a recent study has shown that preventative interventions can reduce the incidence of depression by 21 % (5). Therefore, public health interventions to prevent depression are particularly important. In the face of a multitude of preventive measures, we must focus on areas that are malleable or highly influential, while acknowledging the role of other factors, including diet (6). Ultra-processed foods (UPFs) are becoming dominant in the global food system (7), and are generally energy-dense, rich in refined carbohydrates, saturated fats, and salt, and contain low dietary fiber (8). These foods include savory snacks, industrialized candies and desserts, reconstituted meat products, prepared frozen dishes, and soft drinks (9). Therefore, the study of the association between UPF and depression is likely to provide public health strategies for the prevention of depression.

A growing number of studies have demonstrated the potential health hazards of UPF (10), and we suspect that it may contribute to an increase in depression. Several epidemiological studies (11-13) show a positive association between UPF and depression, but some also suggest that consumption of UPF is not linked to a higher prevalence of depression (14,15). In the current study, we systematically reviewed the literature investigating UPF intake and risk of depression in an attempt to synthesize the current state of the literature, to inform further research, and to provide strategies for the prevention of depression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

STUDY DESIGN

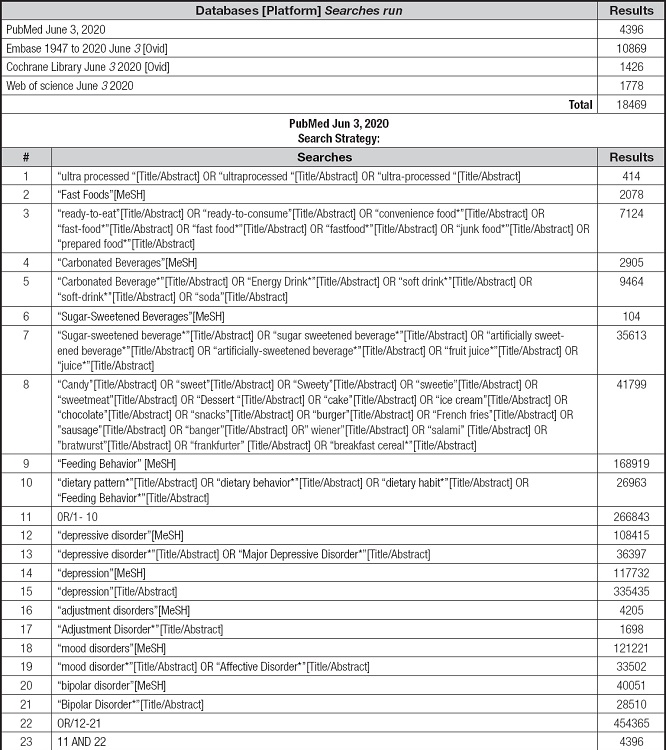

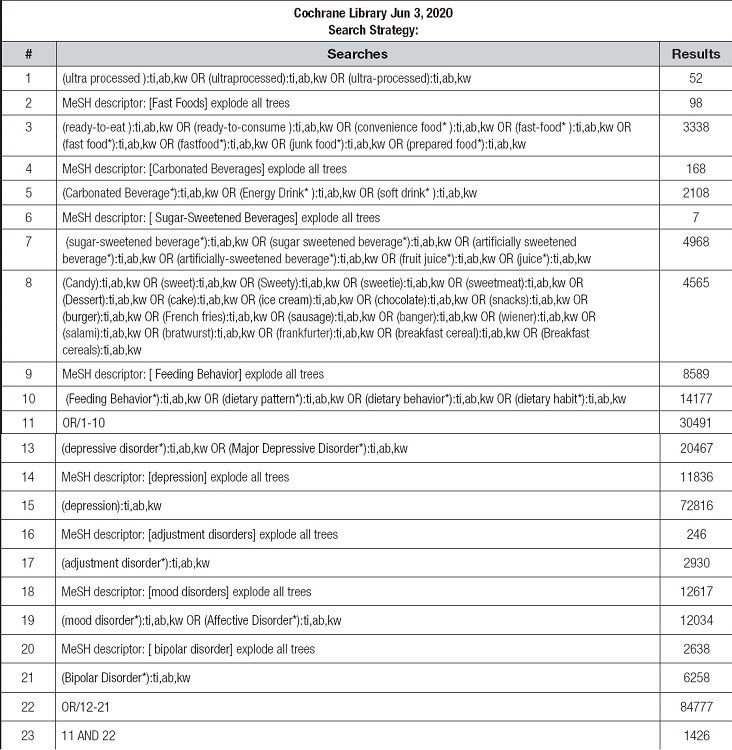

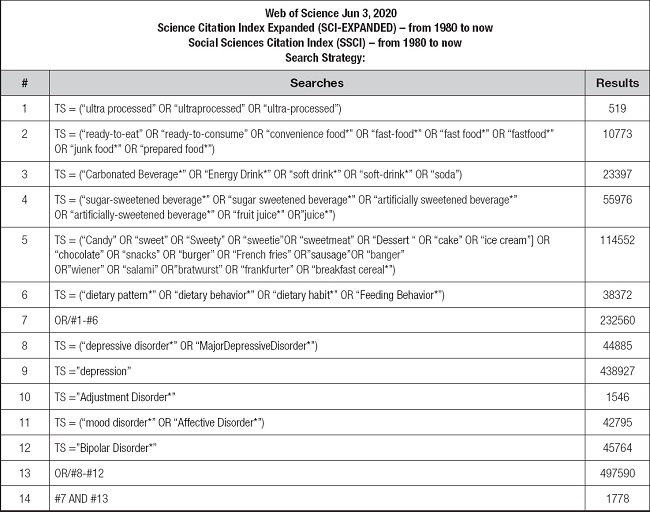

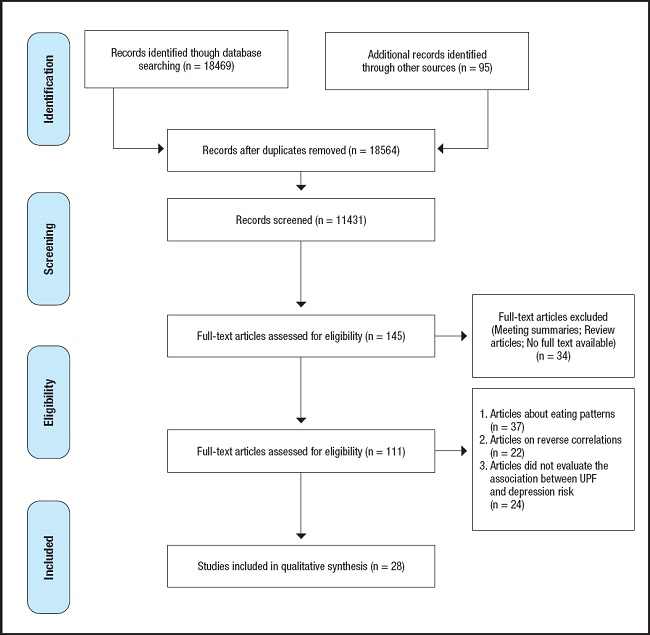

The search used Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, and the review was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) database (CRD42020192648) (16). A systematic review of studies published until June 3, 2020, was performed in PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases with an additional manual search conducted via references of found studies.

INCLUSION/EXCLUSION CRITERIA

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: 1) cohort studies, case-control studies, and cross-sectional studies; 2) the exposure factor was consumption of ultra-processed foods; 3) the outcome factors were depression, depressive symptoms or depressive mood; and 4) the odds ratio (OR), relative risk (RR) or hazard ratio (HR) with 95 % confidence interval (CI) were provided or could be calculated.

Exclusion criteria: 1) Studies of inverse associations (i.e., those that examine the effects of depression, depressive symptoms, or depressed mood on the intake of ultra-processed foods); 2) only the effect of dietary patterns on depression was assessed, and not for a single food group; 3) it did not evaluate the association between UPF and depression risk; and 4) those for which the full text could not be found or that were not published in English.

SEARCH STRATEGY

The search for studies was performed in PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases up to June 2020; the search strategy is shown in the supplementary table I. In addition, a manual search for publications was conducted via analyzing the references of the found studies.

Eight reviewers working independently in pairs of two screened all titles and abstracts following training and calibration exercises; a third reviewer adjudicated conflicts. Full texts of these potentially eligible studies were also independently assessed for eligibility by the pair, and any disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third researcher. This procedure is presented in figure 1.

DATA EXTRACTION

Data extraction was conducted independently by two researchers, and disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third researcher.

Data extracted from the studies included the following: author and publication year; country; study design; sample size; age group evaluated; the percentage of females; methods and instruments used to measure the exposure and outcome variables; variables used to control for confounding and in the mediation analysis (when present), and main results.

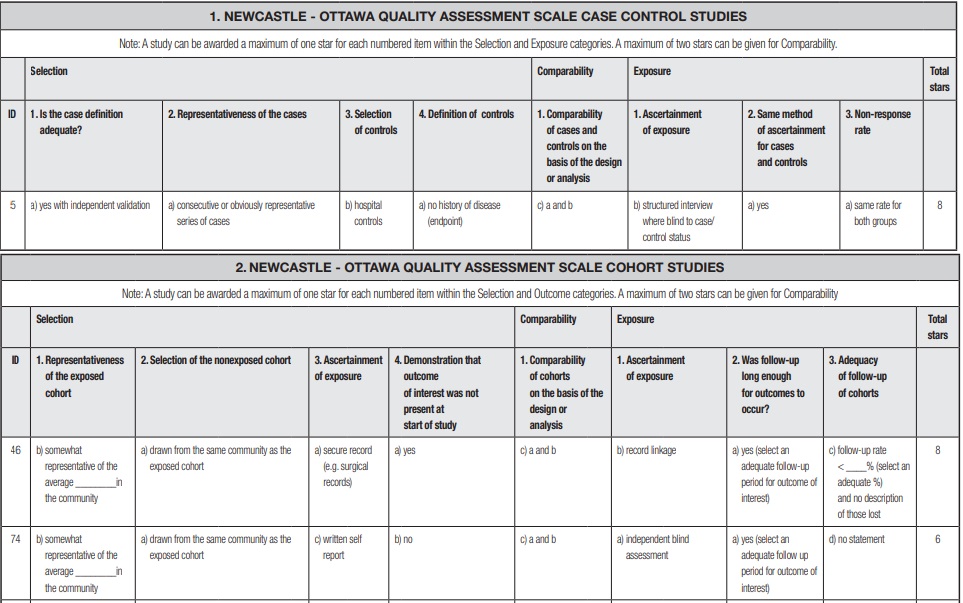

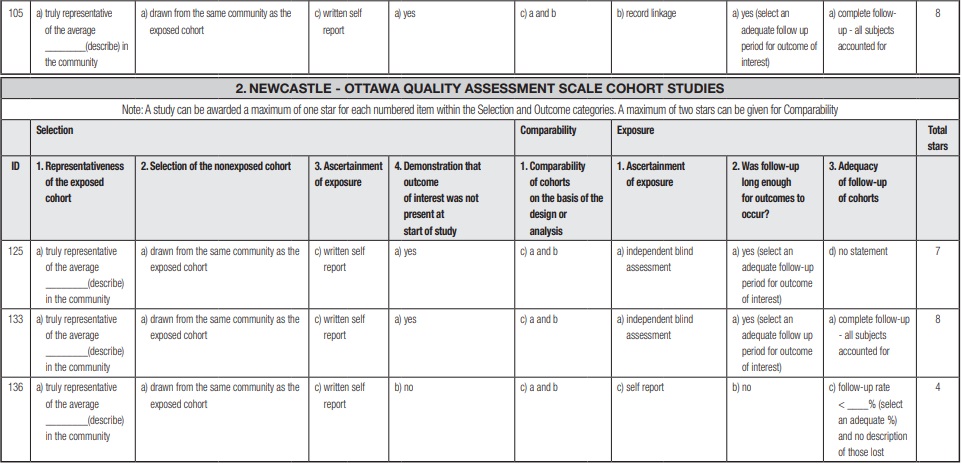

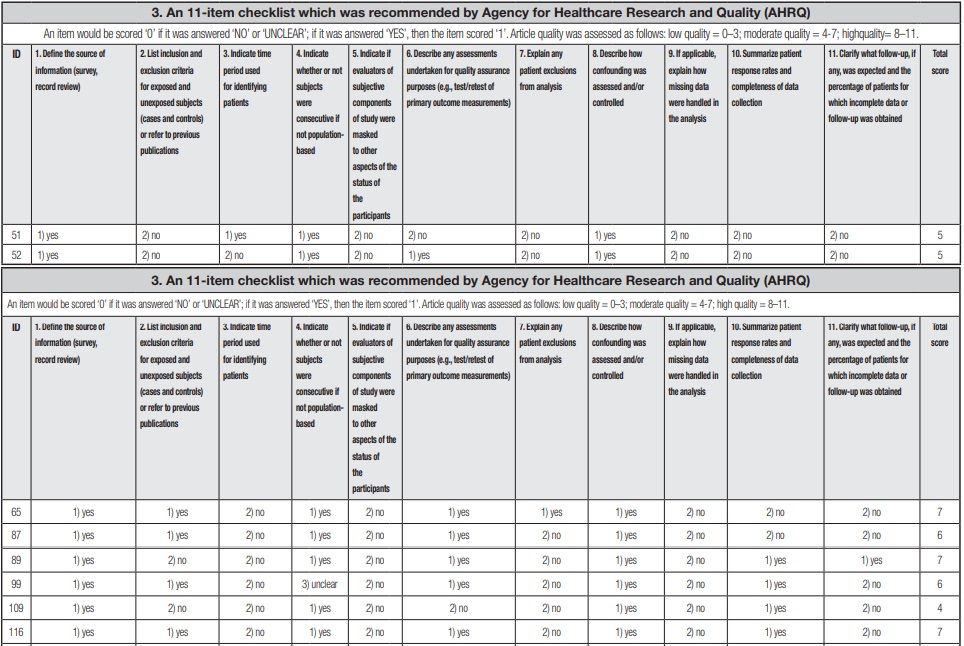

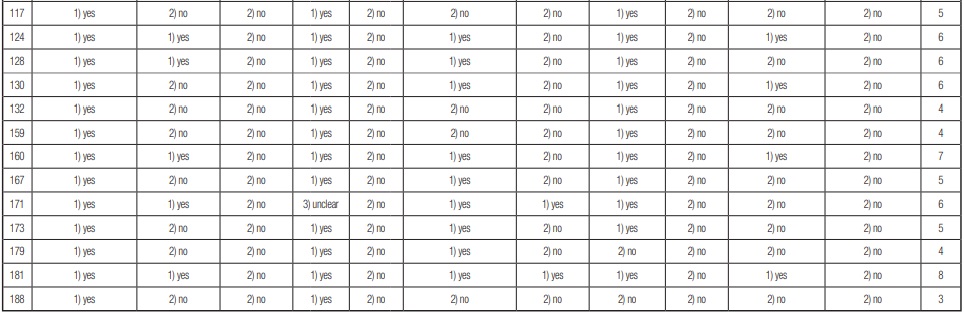

The quality of the included literature was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cohort and case-control studies (17), and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) methodology checklist for cross-sectional studies (18). The detailed evaluation methods are shown in supplementary table II. The results of case-control studies and cohort studies were interpreted based on the commonly assumed criteria and attributed to the following categories: very high risk of bias (0-3 NOS points), high risk of bias (4-6 NOS points), and low risk of bias (7-9 NOS points) (19). Cross-sectional studies were assessed as follows: low quality = 0-3; moderate quality = 4-7; and high quality = 8-11.

RESULTS

STUDY CHARACTERISTICS

The list of studies included and details on the studies are presented in table I. All studies in the table are listed according to study design and year of publication. Among the 28 included studies, the majority were conducted in European countries (10 studies) (11-14,20-25), with additional studies from United States (4 studies) (26-29), China (3 studies) (30-32), Korea (3 studies) (33-35), Iran (2 studies) (36,37), Brazil (1 study) (38), Canada (1 study) (39), Australia (1 study) (40), Mexico (1 study) (41), Japan (1 study) (42), or a combination of countries (1 study) (43). The studied population primarily comprised adults (12 studies) (11-13,21,25-27,30,31,36,38,40), while two focused on the elderly (2 studies) (14,29). Additional studies also examined adolescents (7 studies) (22,28,33-35) and university students (5 studies) (23,24,32,41,43). Two other studies were conducted in special populations, and the inclusion criteria for the subjects were pregnant women and bariatric surgery candidates (20,42). Of the 28 studies, there were cross-sectional studies (21 studies) (20-24,26-28,31-43), cohort studies (6 studies) (11,12,14,15,25,29), and a case-control study (1 study) (30). In 28 studies, the exposure factors were a combination of fast food and soft drinks (10 studies) (14,21,23,24,30,34,36-38,41), soft drinks (7 studies) (25,28,31,40,42,43), energy drinks (5 studies) (22,27,33,35,39), fast food and snacks (3 studies) (13,20,32), ultra-processed foods (2 studies) (11,12), and chocolate (1 study) (26). With regard to sex, the majority of studies were on male and female subjects (24 studies), females only (2 studies) (21,42), and males only (1 study) (27). No gender-related information was reported for 1 additional study (15). The instruments used to measure food consumption included the Food Consumption Frequency Questionnaire (13 studies) (11,13-15,21,23,24,29-31,38,41,42), a questionnaire (8 studies) (28,32,34-37,39,40), specific questions (3 studies) (27,33,43), 24-hour dietary recall (2 studies) (12,26), the Eating Disorders Examination-Questionnaire (1 study) (20), and the Diet and Behaviour Scale (1 study) (22). The Agency for Healthcare Research and Qualification (AHRQ) has recommended quality assessment criteria for observational studies, including the NOS scale for cohort and case-control studies, and 11 items for cross-sectional studies. Of all studies included in the systematic evaluation, 1 case-control study showed low risk of bias (30), 2 of 6 cohort studies were medium risk of bias (14,29) and the remaining 4 showed low risk of bias (11-13,15); and 1 of 21 cross-sectional studies indicated high quality (42), 1 indicated low quality (22), and the rest were ranked as having medium quality (20,21,23,24,26-28,31-41,43). The full details of this evaluation are shown in supplementary table II.

Table I. Summary of the selected studies that investigated the association between UPF and depression.

Table I (cont.). Summary of the selected studies that investigated the association between UPF and depression.

Table I (cont.). Summary of the selected studies that investigated the association between UPF and depression.

Table I (cont.). Summary of the selected studies that investigated the association between UPF and depression.

Table I (cont.). Summary of the selected studies that investigated the association between UPF and depression.

NR: not reported; DABS: Diet and Behaviour Scale; EDE-Q: Eating Disorders Examination-Questionnaire; SDS: Chinese version of Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale; DASS 21: Iranian validated version of depression, anxiety, and stress scale questionnaire 21; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9; CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory-II; MDS: Modified Depression Scale; K6: Kessler 6-item psychological distress scale; WPQ: Wellbeing Process Questionnaire; M-BDI: modification of the Beck Depression Inventory; SCID-I: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV; BMI: body mass index.

GROUPS OF ULTRA-PROCESSED FOODS CONSUMPTION AND DEPRESSION

Four cohort studies included in the systematic review concerned groups of UPF consumption and depression. Three of these showed that UPF consumption was associated with depression risk (11-13). However, one study (14) found that consumption of savory snacks was not associated with a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms. Seven cross-sectional studies showed that the UPF consumption was significantly associated with depression, while a different study (41) indicated the association was only true in women. It therefore may be that eating behaviors are more typical in women, while men may have other ways to manage their negative emotions and stressful situations. It should be noted that a different study (24) also observed that higher consumption of carbohydrate-dense foods such as sweets, cookies, snacks, and fast food was not associated with depressive symptoms scores.

SOFT DRINKS/SWEETENED BEVERAGES/ENERGY DRINKS CONSUMPTION AND DEPRESSION

Several studies explored the relationship between soft drinks and depression, including seven cross-sectional studies (23,24,31,34,40,43) and one cohort study (29). Four studies (29,31,34,40) showed a positive association between soft drink intake and depressive symptoms, but others (23,24,43) showed no such association. For sweetened beverages, one study (30) found no relationship between consumption of sugared beverages and snacks and a prevalence of high depressive symptoms in a case-control study. In the cohort studies (14,15), Elstgeest et al. found a positive association only among women, while Sanchez-Villegas et al. explained sugar-sweetened beverage intake was not associated with a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms. Several cross-sectional studies further observed no association between sugary drink consumption and depression (21,28,41), but Sangsefidi et al. found an inverse association between sweetened drink consumption and depressive features (34,36,37). Regarding the relationship between energy drinks intake and depression, four studies (27,33,35,39) observed that participants who regularly used energy drinks were more likely to be depressed; however, Richards et al. observed no such association (22).

OTHER ULTRA-PROCESSED FOODS CONSUMPTION AND DEPRESSION

In studies assessing the risk of depression with other UPFs (desserts, chocolate, processed cereals), three (26,37,38) found a positive association between regular consumption of sweets and chocolate and depression. However, one study by Mikolajczyk et al. (21,24) controlled for the consumption of cereal products, and no longer found an association between sweet consumption and depressive symptoms.

DISCUSSION

In summary, the majority of studies included in this systematic review showed that UPF consumption is associated with the risk of depression. A lack of correlations in some studies may be due to methodological issues. First, the majority of the study population was generally well represented across the lifespan, but unbalanced samples tended to find no association. For example, people aged ≥ 90 years were oversampled in Elstgeest's study. Intake of UPFs is inherently low in these populations, and other factors such as sleep, socioeconomic status, and other illnesses, may be more important risk factors for depression in older populations (44,45). Furthermore, studies with no or incomplete data on depressive symptoms at baseline or on any follow-up measure were excluded for analysis. This selection bias may also underreport the relationship between them. Meanwhile, Takahashi et al. obtained negative results in pregnant women. Such a finding may be due to the fact that pregnant women's diets change considerably after pregnancy, making it difficult to detect a potential relationship between dietary and the risk of depression (46).

Second, different instruments for depression and food consumption evaluation may also partially explain the differences among studies (47). For example, the included studies utilized more than 10 depression assessment instruments, potentially undermining comparability between studies. In addition, Asian researchers tend to use “Western” measures and criteria when conducting research on mental disorders, and cultural differences may lead to the neglect of symptoms specific to Asian populations (48), leading to an underestimation of any potential associations.

Moreover, adjusting for different confounds when constructing regression models can also lead to differences between findings. In the study of Xia et al., UPF intake was not associated with high depressive symptoms after adjusting for other dietary pattern factor scores. This may be due to the concomitant consumption of large amounts of fruit, offsetting the impact of intake of UPFs. Moreover, among those that did not find any association, most did not adjust for physical activity, educational attainment, income level, or marital status (21-24,30,39,42), because these are important factors in the incidence of depression (49,50). Thus, it is possible that the relationship between food groups and risk of depression may be difficult to detect without consideration of these other factors. Furthermore, these differences may also be related to a number of characteristics, such as the characteristics of subjects, environment, policies, region, or country and its political and health positions.

It is important to note that when analyzing the relationship between UPFs and the risk of depression, we must focus on those cohort studies with a low risk of bias (11-13,15). In these studies, we observed that consumption of UPFs was associated with an increased risk of depression, especially among participants with low physical activity. This suggests that inadequate micronutrient intake may play an important role in the relationship between UPF consumption and depression. In addition, there was compelling evidence that nutrients in processed foods are not accurately delivered to the brain, but that affect physiology in unexpected ways, such as via promoting metabolic dysfunction in instigating depression (11,51). Furthermore, the pro-inflammatory trans-fatty acids rich in UPFs may increase the risk of depression (11,25), and the association between UPF consumption and depression has been observed to be partly due to some of the non-nutritional components used or produced during processing (13). In fact, UPF often contains product additives such as emulsifiers or molecules produced by high-temperature heating that may lead to alterations in the gut microbiota, which are thought to be important in the onset of depression (52). While these aspects were briefly described in some of the included studies, most focused more heavily on the association between UPF and the risk of depression.

There are a few limitations in this systematic review, such as the heterogeneity of UPF consumption and depression assessments, which prevented us from conducting meta-analysis. In addition, most of the included studies were cross-sectional, and it was therefore not possible to determine a causal relationship between UPF and depression.

However, this is the first systematic review to our knowledge that explores UPF consumption and the risk of depression. We showed that majority of studies on the topic of UPF consumption and risk of depression shows a positive association. Future studies should consider the use of validated food intake assessments and standardized depression assessment methods to promote comparability between studies.