Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Anales de Psicología

versión On-line ISSN 1695-2294versión impresa ISSN 0212-9728

Anal. Psicol. vol.31 no.1 Murcia ene. 2015

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.31.1.166571

Evaluating the Credibility of Statements Given by Persons with Intellectual Disability

Evaluación de la credibilidad de relatos de personas con discapacidad intelectual

Antonio L. Manzanero1, Alberto Alemany2, María Recio2, Rocío Vallet1 y Javier Aróztegui1

1 Universidad Complutense de Madrid (Spain)

2 Fundación Carmen Pardo-Valcarce (Spain)

This study is part of the research projects entitled "Entrevista, intervención y criterios de credibilidad en abusos de carácter sexual en personas con discapacidad intelectual" [Interview, Intervention, and Credibility Criteria in Abuse of a Sexual Nature in Persons With Intellectual Disability], financed by the Fundación MLAPFRE, and part of the project entitled "Eliminating Barriers Faced by Victims With Intellectual Disabilities: Police and Judicial Proceedings With Victims of Abuse With Intellectual Disabilities," financed by the International Foundation of Applied Disability Research (FIRAH).

ABSTRACT

The objective of this study was to analyze the features that distinguish statements given by actual and simulated victims with mild to moderate intellectual disability, using the credibility analysis procedure known as Reality Monitoring (RM). Two evaluators trained in credibility analysis procedures using content criteria evaluated 13 true statements and 16 false statements. The results obtained show that there is little difference between the two types of statements when analyzed on the basis of content criteria using the RM procedure. The only criteria that proved to be significant for discriminating between the two types of statements were the amount of details and the length of spontaneous statements obtained through free recall. None of the phenomenological characteristics studied turned out to be significant for discriminating between actual and simulated victims. Graphic representation using high-dimensional visualization (HDV) with all criteria taken into consideration shows that the two types of statements are quite heterogeneous. Cluster analysis can group cases with a 68.75% chance of accuracy.

Key words: Credibility assessment; intellectual disability; content criteria; eyewitness testimony; high-dimensional visualization.

RESUMEN

El objetivo del presente trabajo consistió en analizar las características diferenciales de los relatos emitidos por víctimas reales y simuladas con discapacidad intelectual ligera y moderada mediante el procedimiento de análisis de credibilidad de Control de la Realidad (RM). Dos evaluadores entrenados en los procedimientos de análisis de credibilidad mediante criterios de contenido evaluaron 13 relatos verdaderos y 16 relatos falsos. Los resultados encontrados muestran que existen pocas diferencias entre los dos tipos de relatos. Los únicos criterios que resultan significativos para discriminar entre los dos tipos de relatos son la cantidad de detalles y la longitud de las declaraciones espontáneas obtenidas mediante recuerdo libre. Ninguna de las características fenomenológicas examinadas resultó significativa para discriminar entre víctimas reales y simuladas. La representación gráfica mediante visualización hiperdimensional (HDV) considerando conjuntamente todos los criterios muestra una gran heterogeneidad entre relatos. Un análisis de conglomerados permitió clasificar los dos tipos de relatos con una probabilidad de acierto del 68.75 por ciento.

Palabras clave: Evaluación de credibilidad; discapacidad intelectual; criterios de contenido; testimonio; visualización hiper-dimensional.

Introduction

It has been proposed that lying would be cognitively more complex than telling the truth (Vrij, Fisher, Mann, & Leal, 2006) because it would involve a greater demand for cognitive resources (Vrij & Heaven, 1999). This is reflected in some clichés about persons with intellectual disability that suggest they would not be capable of making up complex lies and, therefore, would be more believable (Bottoms, Nysse-Carris, Harris, & Tyda, 2003). These clichés carry a negative charge, however, that results in persons with ID being viewed as witnesses who are less credible and less capable of giving valid testimony (Henry, Ridley, Perry, & Crane, 2011; Peled, Iarocci, & Connolly, 2004; Sabsey & Doe, 1991; Stobbs & Kebbell, 2003; Thannger, Horton, & Millea, 1990; Valenti-Hein & Schwartz, 1993), which makes persons with ID more vulnerable to crimes (González, Cendra, & Manzanero, 2013). Peled et al. (2004) explored the perceived credibility of young persons with ID who were required to give testimony in a legal setting. Half of the observers were told beforehand that the witness had moderate intellectual disability, and the other half were told that the witness was a person who was developmentally normal. When subsequently questioned about the credibility of the testimonies, they stated that those testimonies given by a person with ID were considered less credible. Henry et al. (2011) evaluated the credibility of children with ID and of developmentally normal children and found that the former, because they gave fewer details, were less credible than the latter. They found no correlation between the credibility evaluations and either mental age or anxiety.

The generally lower credibility attributed to persons with ID suggests an enormous need for a technical credibility analysis procedure that is adapted for this type of victim so that evaluation of their testimony is not left to intuition- which, on most occasions, is biased (Manzanero, Quintana, & Contreras, 2015). Such procedures do not exist at this time, however, which means that persons with ID are often excluded from the justice system or evaluated on the basis of a comparison with children. This situation would be exacerbated by failure to adapt legal and law enforcement procedures to the abilities of these individuals (Recio, Alemany, & Manzanero, 2012). Such adaptations could mitigate this serious situation, for it has been shown that, with sufficient adaptations, persons with ID are capable of identifying an alleged assailant in a line-up (Manzanero, Contreras, Recio, Alemany, & Martorell, 2012), even though they do not perform as well on this type of task, to begin with, as individuals who do not have ID (Manzanero, Recio, Alemany, & Martorell, 2011).

Forensic psychology has proposed various procedures for evaluating credibility through analysis of statement content (Manzanero, 2001). One of these procedures is the Reality Monitoring (RM) technique (Johnson & Raye, 1981; Johnson, Hashtroudi, & Lindsay, 1993) which is suggested for evaluating statement credibility.

RM's basic assumption is that statements based on memories of actual events are qualitatively different from statements that are not based on experience or are simply the product of fantasy, as Johnson and Raye (1981) had shown. According to the original proposition, actual statements would contain more contextual and sensory information and show less allusion to cognitive processes and idiosyncratic information than fabricated statements. Many who do research in this area have shown this to be an erroneous assumption, however, for these differences between the two types of statements have not been consistently found (Masip, Sporer, Garrido, & Herrero, 2005).

The theoretical framework for explaining how statements of different origins may be distinguished is found in the meta-cognitive reality monitoring processes defined by Johnson (Johnson & Raye, 1981; Johnson et al., 1993). Based on their proposals, numerous research studies have been conducted to explore the characteristics that differentiate statements of varying origin, such as memories of actual events, imagination, dreams, fantasies, lies, or false memories derived from post-event information (Diges, 1995; Henkel, Franklin, & Johnson, 2000; Johnson, 1988; Johnson, Kahan, & Raye, 1984; Johnson, Foley, Suengas, & Raye, 1988; Lindsay & Johnson, 1989; Manzanero, 2006, 2009; Manzanero & Diges, 1995; Manzanero, El-Astal, & Aróztegui, 2009; Schooler, Gerhard, & Loftus, 1986; Suengas & Johnson, 1988).

In a first approximation, Johnson and Raye (1981) proposed that there are four types of essential attributes by which we could differentiate between the two types of information stored in memory. Memories of perceptive origin would have more contextual and sensory attributes and more semantic details, while self-generated memories would contain more information about cognitive operations. As subsequent research was expanding the list of differentiating attributes (see Table 1), the data was showing, simultaneously, that the presence of these distinctive features depends on the influence of a host of factors.

Among other factors, the presence of characteristic features in true statements, as opposed to statements arising from imagined or suggested facts, would depend on the activation (Diges, Rubio, & Rodríguez, 1992), previous knowledge (Diges, 1995), the perceptive modality (Henkel et al., 2000), the preparation (Manzanero & Diges, 1995), the time delayed (Manzanero, 2006), the individuaos age (Comblain, D'Argembeau, & Van der Linden, 2005), the asking of questions and multiple recall (Manzanero, 1994; Strómwall, Bengtsson, Leander, & Granhag, 2004), and contextual factors (Campos & Alonso-Quecuty, 1998), as well as the type of design used in the research conducted (Bensi, Gambetti, Nori, & Giusberti, 2009).

On the other hand, the wide variability in memory origin means that the characteristics differentiating fantasies, lies, dreams, and post-event information are not the same. Even for each modality, however, there are varying degrees of remove from the actual information. For example, changing a small detail of an actual event-even a very important detail, such as whether the role played in the event was witness or protagonistis not the same thing as fabricating the entire event (Manzanero, 2009). In any case, false statements are never entirely fabricated but originate, in part, from information perceived from different sources that is re-elaborated to create a new statement. Likewise, characteristics of the statements could vary in relation to the participant's ability to generate a plausible statement.

Some previous studies have shown that criteria traditionally used to distinguish actual victims from simulated victims, such as the emotions associated with their statements, would not be useful with the ID population (Manzanero, Recio, Alemany, & Pérez-Castro, 2013). We are not aware, however, of any study on the characteristics that differentiate true statements from false statements in this population. This was the reason for conducting the following experiment: to analyze the differences between statements given by actual and simulated victims with ID, using the features proposed under the framework of Reality Monitoring (RM) processes-the ultimate purpose being to develop procedures adapted for these victims.

Previous research studies (Manzanero, López, & Aróztegui, submitted) using participants with no intellectual disability, who were asked to assume the perspective of either false protagonist or actual bystander for an automobile accident, showed that the former were more heterogeneous, phenomenologically, than the latter, although the two types of statements differed on very few points (Figure 1). The hope was that similar results would be obtained in this study.

Method

Participants

Twenty-nine persons with intellectual disability participated in the study. Thirteen of the participants were actual victims, with a mean IQ of 60.72 (SD=9.67) and a mean chronological age of 35.18 years (SD=7.16), and sixteen were simulated victims, with a mean IQ of 59.30 (SD =9.44) and a mean chronological age of 33.75 years (SD =6.78).

Procedure

To conduct this research, a real event was chosen that happened two years ago-a day trip taken by a group of persons with ID from the Carmen Pardo-Valcarce Foundation, during which the bus they were traveling in caught fire. A researcher selected the participants, all of comparable IQ, on the basis of criteria for the "true" group-did go on the day trip-and the "false" group-did not go on the day trip but knew about the event from references made to it. All persons with ID who participated in the study (or their legal guardians) signed a consent for voluntary participation. Each of the persons with ID was given instructions and informed of the purpose of the research. In addition, those participants who did not go on the day trip were given a summary of the most important information about the trip, such as the location, the trip's primary complication, and how the day went. We increased the ecological validity of our study by encouraging all participants in the two groups to do their best when giving their testimony. However, to avoid putting them under too much pressure to make the interviewer believe their testimony, we chose an incentive that was not stressful-they would be invited for a soda if they succeeded in convincing the interviewer that they had, in fact, experienced the event. In addition, the persons with ID who belonged to the false statement group were told explicitly that they had the option to lie and were assured there would be no negative consequences if they did so, thereby preventing undue tension.

Two "blind" researchers, experts at interviewing and taking testimony, interviewed each participant individually. An audiovisual recording was made of all interviews. The same instructions were given for all interviews conducted: "We want you to tell us what happened when you went on the day trip and the bus caught fire... from beginning to end, with as much detail as you can give. We want you to tell us even things that you might think are not very important." Once the free statement was obtained, all participants were asked the same questions: Who were you with? Where was it? Where were you going? What did you yourself do? and What happened afterwards? The interviews were conducted in random order.

The interview tapes were transcribed to facilitate analysis of the phenomenological characteristics of the statements, with any reference to the participant's group eliminated. Two trained evaluators assessed each statement individually on each of the content criteria proposed in the RM procedure (see Table 2), and then an interjudge agreement was reached. The degree of agreement between encoders [AI = agreements / (agreements + disagreements)] for all measurements analyzed was greater than .80 (Tversky, 1977).

For correcting amount of detail, a chart was made of the micropropositions, describing as objectively as possible what happened in the actual event.

The remaining measurements are defined as follows:

- sensory information: information referring to sensory and geographical data that appeared in reality: colors, sizes, positions.

- contextual information: information referring to spatial and temporal data about the area where the accident took place

- allusions to cognitive processes: information in which some cognitive process is explicitly mentioned: I imagined, I saw, I heard, I remember. my attention was focused on, something makes me think.

- hesitant expressions: implies doubt about what is being described (it could be, it seems that, I think that, it's likely...)

- irrelevant information: information that is correct but is not a central part of the event

- explanations: information that expands upon the description of the facts by providing a functional reference

- self-references: references the participant makes to himself when describing the event

- exaggerations: descriptions that, by being excessive or lacking, distort the facts

- personal opinions and comments: assessments of aspects of the event and the participant's personal additions

- Fillers: pet words or phrases that are repeated out of habit throughout the statement

- pauses: silences during the participant's narration of the facts

- spontaneous corrections: corrections occurring in the description of the facts

- changes of order: alteration of the event's natural order of occurrence: introduction, development, and conclusion

- length: number of words in the statement

All measurements, with the exception of length, were measured by counting the number of times each one occurred in the statements.

Results

Factorial analysis (ANOVA) of the content criteria proposed in RM showed that only amount of detail [F (1.31)=19.800, p <.01, η2=.398, 1-β= 990] and length of statement [F(1.31)=5.526,p <.05, η2 =.156, 1-0 =.624] were sigmficant. There were no significant effects on the rest of the criteria. Table 2 shows the mean scores and standard deviations for false statements and true statements and the totals for each criterion.

As a way to appreciate the differences between the two types of statements, with all the measurements analyzed taken into consideration, the data was represented graphically through a high-dimensional visualization (HDV) technique used in other studies (Buja et al., 2008; Manzanero et al., 2009; Steyvers, 2002), and a cluster analysis was performed to classify participants into two groups.

As may be appreciated from the graph in Figure 2, one possible explanation for the scant difference between the two types of statements stems from intersubject variability, which would indicate that this technique has low diagnostic capability. If we tried to classify the two types of statements based on all the phenomenological characteristics considered in the RM technique, K-Means Cluster Analysis grouped 25 cases as false and 7 as true. When cluster A is considered equal to simulation and B equal to actual, the false statements were correctly classified in 16 cases (94.1% of total false statements), while true statements were correctly classified in 6 cases (40% of total true statement). As may be observed in HDV graph, the main reason is that the actual victims' statements are more heterogeneous than the simulated victims' statements-for those of the former group are, phenomenologically, more similar to those of the latter group, in some cases.

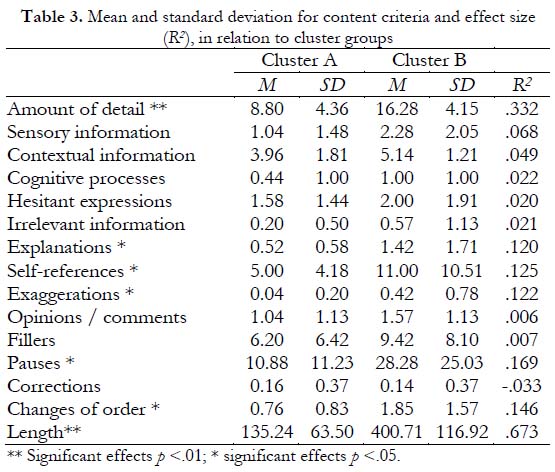

When cluster groups are considered, factorial analysis (ANOVA) of the content criteria proposed in RM showed that amount of detail [F(1.31)=16.375, p <.01, η2=.353, 1-β= 975], explanations [F(1.31)=5.218, p <.05, η2=.148, 1-β= 599], self-references [F(1.31)=5.449, p <.05, η2=.154, 1-β=618], exaggerations [F(1.31)=5.300, p <.05, η2=.150, 1-β=.606], pauses [F(1.31)=7.320, p <.05, η2=.196, 1-β= 745], and length of statement [F(1.31)=64.663,p <.01, η2=.683, 1-β=.1.000] were significant (see Table 3).

Conclusions

As noted in the introduction, there is an abundance of literature that points out inconsistencies in the attributes differentiating true statements from false statements, as well as the irrelevance of RM procedure criteria, on the whole, for distinguishing between true and false statements. Likewise, from the results obtained in this study, we can conclude that the above-mentioned technique is also not valid for distinguishing between statements given by actual and simulated victims with ID. The lack of effect on most of the criteria would be due to an enormous variability and, in some cases, to the floor effect for, generally speaking, the statements were not very rich, phenomenologically.

Of the 15 criteria analyzed, however, there were two (amount of detail and length) that were significant for discriminating between the two types of statements and, therefore, could be of some help in distinguishing the origin of the statements. Thus, the temptation would be to use only these two criteria for an objective analysis of credibility and to discard the remaining criteria.

This approach, which would mean fewer criteria, should be discarded, however, because whether these two criteria are present most likely depends on a great variety of factors, such as the type of event described, the time elapsed, and the witness's abilities, for example. If the criteria that enable us to distinguish between true and false statements are the amount of detail and the length of the statement-the first also being especially important in evaluating a testimony as "true"-what happens with all those individuals who have limited vocabulary, semantic and autobiographical memory deficits (without which they cannot satisfactorily reproduce conversations), or difficulty situating events in a given context? The majority of persons with ID have trouble relating a vivid event in rich detail; they tend to be even less likely than the population without ID to include important details of the event (Dent, 1986; Kebbell & Wagstaff, 1997; Perlman, Ericson, Esses, & Isaacs, 1994).

By the same token, many persons with ID also have great difficulty situating events in time and space (Bailey et al., 2004; Landau & Zukowsky, 2003). Therefore, using only the two criteria shown to be significant in the study, one runs the risk of issuing an erroneous assessment of credibility-and the revictimization that would result.

Discarding the 13 non-significant criteria does not seem appropriate either, however, for as the cluster analysis of all criteria shows, we would still be able to distinguish 68.75% of the statements correctly, even though they vary widely. The problem is that, even with sound decision-making ability, it is difficult to take 15 criteria into consideration simultaneously-and, in any case, there is an 60% chance of a false positive. Let us remember that, in forensic psychology, the proposed maximum rate of error for a technique to be accepted as valid is 0.4% (Manzanero & Muñoz, 2011; Rassin, 1999; Wagenaar, Van Koppen, & Crombag, 1993).

Further research with these criteria, along with a system of analysis that would enable all indicators to be taken into account in making a decision, might shed more light on content-based lie detection procedures.

These results, however, are contrary to those found in the previous research mentioned in the introduction, which was conducted with developmentally normal persons (Manzanero, et al., submitted), where the dispersion of points on the graph was observed to be greater for statements given by participants assuming the perspective of false protagonist than for those assuming the actual perspective (see Figure 1). In that study, in contrast to this one, the two types of statements could be distinguished with a 94.3% chance of accuracy. At any rate, this difference in the results could be accounted for by differences between the two studies in terms of not only the participants but also the events -for an actual event was used for the present study, but a filmed event and a different type of fabrication was used for the study with participants who did not have ID. It would be advisable to conduct further research with different events and different types of fabrication so that the results could be generalized.

Limitations of the Study

Although the individuals available to us for the sample were persons with mild and moderate ID-the deficit seen in 80% and 10%, respectively, of persons with ID (Fletcher, Loschen, Stavrakaki, & First, 2007)-we are adamant that there is a need for research in this field with the group of persons who have greater difficulty giving their testimony. In future research studies, testimonies given by persons with more severe ID should be analyzed on the basis of these criteria because we understand that, the more severe the disability, the more difficult it is for the individual to narrate with sufficient detail, to situate an event in a context, and to reproduce conversations. Thus, in a population of persons with severe ID or with a specific syndrome involving language disorders, perhaps the credibility criteria that prove to be significant for distinguishing between true and false statements would be different.

Then again, the results obtained would be applicable only to those statements originating from an actual memory and to false statements generated from information about an event presented schematically. Research on persons with ID would have to be expanded to include other types of statements, such as those arising from false memories or those originating in the imagination. In any case, false statements, regardless of their origin, are never entirely fabricated but originate, in part, from various sources of information and are developed to create something new.

In conclusion, in light of our results, we may affirm that there are complexities involved in analyzing the credibility of testimony given by an adult person with ID and, even beyond that, in designing the supportive procedures required to obtain a valid testimony. Given the bias that may condition our intuitive credibility evaluation in persons with ID, and because such an evaluation carries a significant margin of error, it is absolutely essential that, in a law enforcement or legal setting, individuals who specialize in ID would be on hand when the testimony of a person with ID is to be evaluated. By the same token, prior to evaluating the testimony, the individual must be evaluated with regard to those abilities that could impact each of the credibility criteria used to distinguish between true and fabricated statements in this population.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the persons with intellectual disability from Sheltered Employment and the Sheltered Workshops at Fundación Carmen Pardo-Valcarce who collaborated on this study as actual and simulated victims.

References

1. Bailey, Jr., D. B., Roberts, J. E., Hooper, S. R., Hatton, D. D., Mirrett, P. L., Roberts, J. E. & Schaaf, J. M. (2004). Research on fragile X syndrome and autism: implications for the study of genes, environments and developmental language disorders. In M. L. Rice & S.F. Warren (Eds.), Developmental language disorders: From phenotypes to etiologies (pp.121-150), Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [ Links ]

2. Bekerian, D. A., & Dennett, J. L. (1992). The truth in content analyses of a child's testimony. In F. Lösel, D. Bender, & T. Bliesener (Eds.), Psychology and Law. International Perspectives (pp. 335-344). Berlin: W de Gruyter. [ Links ]

3. Bensi, L., Gambetti, E., Nori, R., & Giusberti, F. (2009). Discerning truth from deception: The sincere witness profile. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 1 (1), 101-121. Retrieved from http://www.usc.es/sepjf/images/documentos/volume_1/Bensi.pdf. [ Links ]

4. Bottoms, B. L., Nysse-Carris, K. L., Harris, T., & Tyda, K. (2003). Juror's perceptions of adolescent sexual assault victims who have intellectual disabilities. Law and Human Behavior, 27, 205-227. Doi:10.1023/A:1022551314668. [ Links ]

5. Buja A., Swayne D. F., Littman M., Dean N., Hofmann H., & Chen L. (2008). Data Visualization with Multidimensional Scaling. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 17 (2), 444-472. Doi:10.1198/106186008X318440. [ Links ]

6. Campos, L., & Alonso-Quecuty, M. L. (1998). Knowledge of crime context: Improving the understanding of why the cognitive interview works. Memory, 6, 103-112. Doi: 10.1080/741941602. [ Links ]

7. Comblain, C., D'Argembeau, A., & Van der Linden, M. (2005). Phenomenal characteristics of autobiographical memories for emotional and neutral events in older and younger adults. Experimental Aging Research, 31 (2), 173-89. Doi: 10.1080/03610730590915010. [ Links ]

8. Dent, H. (1986). An experimental study of the effectiveness of different techniques of interviewing mentally handicapped child witnesses. British Journal of Clinica/ Pychology, 25, 13-17. Doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1986.tb00666.x. [ Links ]

9. Diges, M. (1995). Previous knowledge and delay in the recall of a filmed event. In G. Davies, S. M. A. Lloyd-Bostock, M. McMurran, & C. Wilson (Eds.), Psychology, law and criminal justice. International developments in research and practice (pp. 46-55). Berlin: W. de Gruyter. [ Links ]

10. Diges, M., Rubio, M. E., & Rodríguez, M.C. (1992). Eyewitness testimony and time of day. In F. Lösel, D. Bender, & T. Bliesener (Eds.), Psychology and Law. International Perspectives (pp. 317-320). Berlin: W de Gruyter. [ Links ]

11. Fletcher, R., Loschen, E., Stavrakaki, C., & First, M. (Eds.), (2007). Diagnostic Manual - Intelectual Disability (DM-ID): A Textbook of Diagnosis of Mental Disorders in Persons with Intellectual Disability. Kingston, NY: NADD Press. [ Links ]

12. González, J. L., Cendra, J., & Manzanero, A. L. (2013). Prevalence of disabled people involved in Spanish Civil Guard's police activity. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34, 3781-3788. Doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2013.08.003. [ Links ]

13. Henkel, L. A., Franklin, N., & Johnson, M. K. (2000). Cross-modal source monitoring confusions between perceived and imagined events. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition, 26 (2), 321-335. Doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.26.2.321. [ Links ]

14. Henry, L., Ridley, A., Perry, J., & Crane, L. (2011). Perceived credibility and eyewitness testimony of children with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 55 (4), 385-391. Doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2011.01383.x. [ Links ]

15. Johnson, M. K. (1988). Reality Monitoring: An experimental phenomenological approach. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 117 (4), 390-394. Doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.117.4.390. [ Links ]

16. Johnson, M. K., Hashtroudi, S., & Lindsay, D. S. (1993). Source monitoring. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 3-28. Doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.1.3. [ Links ]

17. Johnson, M. K., Foley, M. A, Suengas, A. G., & Raye, C. L. (1988). Phenomenal characteristics of memories for perceived and imagined autobiographical events. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 117 (4), 371-376. Doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.117.4.371. [ Links ]

18. Johnson, M. K., Kahan, T. L., & Raye, C. L. (1984). Dreams and reality monitoring. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 113 (3), 329-344. Doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.113.3.329. [ Links ]

19. Johnson, M. K., & Raye, C. (1981). Reality monitoring. Psychological Review, 88, 67-85. Doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.88.1.67. [ Links ]

20. Kebbell, M. R., & Wagstaff, G. F. (1997). Why do the police interview eyewitnesses? Interview objectives and the evaluation of eyewitness performance. Journal of Psychology, 131, 595-601. Doi: 10.1080/00223989709603841. [ Links ]

21. Landau, B., & Zukowsky, A. (2003). Objects, Motions and Paths: spatial language in children with Williams Syndrome. Developmental Neuropsychology, 23, 105-137. Doi: 10.1080/87565641.2003.9651889. [ Links ]

22. Lindsay, D. S., & Johnson, M. K. (1989). The eyewitness suggestibility effect and memory for source. Memory and Cognition, 17, 349-358. Doi: 10.3758/BF03198473. [ Links ]

23. Manzanero, A. L. (1994). Recuerdo de sucesos complejos: Efectos de la recuperación múltiple y la tarea de recuerdo en la memoria. (Recall of complex events: Effects of multiple retrieval and task on memory) Anuario de Psicología Jurídica/Annual Review of Legal Psychology, 4, 9-23. Retrieved from http://eprints.ucm.es/6175/1/Anuario_94.pdf. [ Links ]

24. Manzanero, A. L. (2001). Procedimientos de evaluación de la credibilidad de las declaraciones de menores víctimas de agresiones sexuales. Revista de Psicopatología Clínica, Legal y Forense, 1 (2), 51-71. Retrieved from http://eprints.ucm.es/6189/1/psicopatologia.pdf. [ Links ]

25. Manzanero, A. L. (2006). Do perceptual and suggested accounts actually differ? Psychology in Spain, 10 (1), 52-65. Retrieved from http://eprints.ucm.es/11380/1/psychology_in_spain.pdf. [ Links ]

26. Manzanero, A. L. (2009). Análisis de contenido de memorias autobiográficas falsas (Criteria content analysis of false autobiographical memories). Anuario de Psicología Jurídica/Annual Review of Legal Psychology, 19, 61-72. Retrieved from http://eprints.ucm.es/11019/1/falsas_memorias_imp.pdf. [ Links ]

27. Manzanero, A. L., Contreras, M. J., Recio, M., Alemany, A., & Martorell, A. (2012). Effects of presentation format and instructions on the ability of people with intellectual disability to identify faces. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 33, 391-397. Doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.09.015. [ Links ]

28. Manzanero, A. L., & Diges, M. (1995). Effects of preparation on internal and external memories. In G. Davies, S. M. A Lloyd-Bostock, M. McMurran, & C.Wilson (Eds.), Psychology, law and criminaljustice. International developments in research and practice (pp. 56-63). Berlin: W. De Gruyter & Co. Retrieved from http://eprints.ucm.es/6174/1/oxford_95.pdf. [ Links ]

29. Manzanero, A. L., El-Astal, S., & Aróztegui, J. (2009). Implication degree and delay on recall of events: An experimental and HDV study. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 1 (2), 101-116. Retrieved from http://eprints.ucm.es/11383/1/Manzanero_et_al_2009.pdf. [ Links ]

30. Manzanero, A. L., López, B., & Aróztegui, J. (submitted). Underlying processes behind false perspective production: an exploratory study. [ Links ]

31. Manzanero, A. L., & Muñoz, J. M. (2011). La prueba pericial psicológica sobre la credibilidad del testimonio: Reflexiones psico-legales. Madrid: SEPIN. Retrieved from http://eprints.ucm.es/12544/1/credibilidad_del_testimonio.pdf. [ Links ]

32. Manzanero, A. L., Quintana, J. M., & Contreras, M. J. (2015). (The null) Importance of police experience on intuitive credibility of people with intellectual disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 36 (1), 191-197. Doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2014.10.009. [ Links ]

33. Manzanero, A. L., Recio, M., Alemany, A., & Martorell, A. (2011). Identificación de personas y discapacidad intelectual. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica/Annual Review of Legal Psyychology, 21, 41-48. Doi: 10.5093/jr2011v21a4. [ Links ]

34. Manzanero, A. L., Recio, M., Alemany, A., & Pérez-Castro, P. (2013). Factores emocionales en el análisis de credibilidad de las declaraciones de víctimas con discapacidad intelectual/ Emotional factors in credibility assessment of statements given by victims with intellectual disabilities. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica/Annual Review of Legal Psychology, 23, 21-24. Doi:10.5093/aj2013a4. [ Links ]

35. Masip, J., Sporer, S. L., Garrido, E., & Herrero, C. (2005). The detection of deception with the reality monitoring approach: a review of the empirical evidence. Psychology, Crime and Law, 11 (1), 99-122. Doi: 10.1080/10683160410001726356. [ Links ]

36. Peled, M., Iarocci, G., & Cannolly, D. A, (2004). Eyewitness testimony and perceived credibility of youth with mild intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 18 (7), 669-703. Doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2003.00559.x. [ Links ]

37. Perlman, N. B., Ericson, K, I., Esses, V. M., & Isaacs, B. J. (1994). The developmentally handicapped witness . Law and Human Behaviour, 18, 171-187. Doi: 10.1007/BF01499014. [ Links ]

38. Porter, S., & Yuille, J. C. (1996). The language of deceit: an investigation of the verbal cues to deception in the interrogation context. Law and Human Behavior, 20, 443-458. Doi: 10.1007/BF01498980. [ Links ]

39. Rassin, E. (1999). Criteria-Based Content Analysis: The less scientific road to truth. Expert Evidence, 7, 265-278. Doi: 10.1023/A:1016627527082. [ Links ]

40. Recio, M., Alemany, A., & Manzanero, A. L. (2012). La figura del facilitador en la investigación policial y judicial con víctimas con discapacidad intelectual. Siglo Cero. Revista Española sobre Discapacidad Intelectual, 43(3), 54-68. Retrieved from http://eprints.ucm.es/16309/1/siglocero_2012.pdf. [ Links ]

41. Sabsey, D. & Doe, T. (1991) Patterns of sexual abuse and assault. Sexuality and Disability, 9, 243-259. Doi: 10.1007/BF01102395. [ Links ]

42. Schooler, J., Gerhard, D., & Loftus, E. (1986). Qualities of unreal. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition, 12, 171-181. Doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.12.2.171. [ Links ]

43. Sporer, S. L., & Sharman, S. J. (2006). Should I believe this? Reality monitoring of accounts of self-experienced and invented recent and distant autobiographical events. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 20, 837-854. Doi: 10.1002/acp.1234. [ Links ]

44. Steller, M. (1989). Recent developments in statement analysis. In J. C. Yuille (Ed.), Credibility assessment (pp. 135-154). Netherland: Kluwer Academic Publishers. [ Links ]

45. Steller, M., & Köehnken, G. (1989). Criteria-based statement analysis. In D. C. Raskin (Ed.), Psychological methods in criminal investigation and evidence (pp. 217-245). New York: Spinger. [ Links ]

46. Steyvers, M. (2002). Multidimensional scaling. In Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science. (pp. 1-7). London: MacMillan. [ Links ]

47. Stobbs, G., & Kebbell, M. (2003). Juror's perception of witnesses with intellectual disabilities and influence of expert evidence. Journal of Appplied Research in Intellectual disabilities, 16, 107-114. Doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3148.2003.00151.x. [ Links ]

48. Strömwall, L. A., Bengtsson, L., Leander, L., & Granhag, P. A. (2004). Assessing children's statements: The impact of a repeated Experience on CBCA and RM ratings. Applied Cognitive Psychology,18, 653-668. Doi: 10.1002/acp.1021. [ Links ]

49. Suengas, A. G., & Johnson, M. K. (1988). Qualitative effects of rehearsal on memories for perceived and imagined complex events. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 117 (4), 377-389. Doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.117.4.377. [ Links ]

50. Tharinger, D., Horton, C., Millea, S. (1990). Sexual abuse and exploitation of children and adults with mental retardation and other handicaps. Child abuse and Neglect, 14, 301-312. Doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(90)90002-B. [ Links ]

51. Tversky, A. (1977). Features of similarity. Psychological Review, 84, 327-352. Doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.4.327. [ Links ]

52. Undeutsch, U. (1982). Statement reality analysis. In A. Trankell (Ed.), Reconstructing the past (pp. 27-56). Stockholm: Norstedt and Soners. [ Links ]

53. Valenti-Hein, D. C, & Schwartz, L. D. (1993). Witness competency in people with mental retardation: implications for prosecution of sexual abuse. Sexuality and Disability, 11, 287-294. Doi: 10.1007/BF01102173. [ Links ]

54. Vrij, A. (2005). Criteria-Based Content Analysis: A Qualitative Review of the First 37 Studies. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 11 (1), 3-41. Doi: 10.1037/1076-8971.11.1.3. [ Links ]

55. Vrij, A., Akehurst, L., Soukara, S., & Bull, R. (2004). Detecting deceit via analysis of verbal and nonverbal behaviour in children and adults. Human Communication Research, 30 (1), 8-41. Doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2004.tb00723.x. [ Links ]

56. Vrij, A., Fisher, R., Mann, S., & Leal, S. (2006). Detecting deception by manipulating cognitive load. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10, 141-142. Doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.02.003. [ Links ]

57. Vrij, A., & Heaven, S. (1999). Vocal and verbal indicators of deception as a function of lie complexity. Psychology, Crime, & Law, 5, 203-215. Doi: 10.1080/10683169908401767. [ Links ]

58. Wagenaar, W. A., Van Koppen, P. J. & Crombag, H. F. M. (1993). Anchored narratives: The psychology of criminal evidence. London: Harvester Press. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Antonio Manzanero.

Facultad de Psicología.

Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

28223 Madrid (España).

E-mail: antonio.manzanero@psi.ucm.es

Article received 21-1-2013

Revision received 16-4-2013

Accepted 25-7-2013