Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Anales de Psicología

versión On-line ISSN 1695-2294versión impresa ISSN 0212-9728

Anal. Psicol. vol.32 no.2 Murcia may. 2016

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.32.2.218301

A review of the dissociative disorders: from multiple personality disorder to the posttraumatic stress

Una revisión de los trastornos disociativos: de la personalidad múltiple al estrés postraumático

Modesto J. Romero-López

Departamento de Psicología Clínica, Experimental y Social, Universidad de Huelva (Spain).

ABSTRACT

In this paper we review the idea of dissociation, dissociative disorders and their relationship with the processes of consciousness. We will deal specifically with multiple personality disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Both polarize the discussion of diagnostic categories with dissociative symptoms. This review compares the initial ideas (one century old) with the current scenario and emerging trends in research, which are relating cognitive processes and dissociative phenomena and disorders from a neuroscientific approach. We discuss the ideas on dissociation, hypnosis and suicide associated with these disorders. There seems to be a lack of consensus as to the nature of dissociation with theoretical, empirical and clinical implications.

Key words: Dissociative disorders; multiple personality disorder; post-traumatic stress disorder; dissociative phenomena; hypnosis; suicide ideation.

RESUMEN

Este trabajo trata la idea de disociación, los trastornos disociativos y su relación con los procesos de conciencia. Se centra en el trastorno de personalidad múltiple y el trastorno de estrés postraumático, desde la perspectiva del diagnóstico y del tratamiento. Ambos grupos de trastornos polarizan el debate sobre las categorías diagnósticas con síntomas disociativos. Se revisan las ideas sobre disociación, hipnosis y suicidio asociadas a estos trastornos. Parece darse una falta de consenso en cuanto a la naturaleza misma de la disociación con implicaciones teóricas, empíricas y clínicas. Completa esta revisión la comparación desde sus inicios, hace poco más de un siglo, con el panorama actual y las nuevas tendencias en las investigaciones que desde las neurociencias están relacionando los procesos cognitivos con los fenómenos y trastornos disociativos.

Palabras clave: trastornos disociativos; trastorno de personalidad múltiple; trastorno de estrés postraumático; fenómenos disociativos; hipnosis; ideación suicida.

Introduction: history, definition and epidemiology

This paper focuses on dissociation, dissociative disorders and their relationship with processes of consciousness. It examines the multiple personality disorder (dissociative identity) and posttraumatic stress disorder from a diagnostic and treatment perspective.

Ideas about dissociation, hypnosis and suicide are historically associated with those disorders. After more than a century of research, our knowledge about dissociative phenomena has not changed substantially. New investigations from a neuroscientific point of view, which associate cognitive processes with dissociations, are slowly changing that.

Dissociative experiences are common in our daily lives, even if dissociative disorders are relatively rare. The most usual are autoscopic phenomena or out of body experiences, automatic writing or speaking, auras, auditory and visual hallucinations, conversion symptoms, somnambulism, flashbacks and episodes of trauma or past abuse that have been forgotten, repressed or dissociated (Fraser, 1994). These dissociative experiences seem to be linked to certain personality traits, whether or not the subject is suggestible, introversion, tendency to fantasy and experiences of depersonalization and fugue. Whenever a subject presents these factors, he is considered to have dissociative tendency. They are risk factors to develop dissociative disorders (de Ruiter, Elzinga & Phaf, 2006). Interculturality is a main element to take into account when studying these disorders. Dissociative phenomena are not always considered pathological.

They are a frequent and accepted expression of culture and religious traditions of many societies. However, there are some culturally defined syndromes which cause discomfort and deterioration that are considered pathological and are characterized by dissociation.

The first systematic study on dissociation was possible thanks to Pierre Janet in 1889 (Kihlstrom, Glisky & Angiulo, 1994; Putnam, 1989). This study proposed that new experiences are generally integrated in the memory though emotions, thought, and behaviours associated to those experiences. Their integration in the memory will depend on their cognitive evaluation. Traumatic experiences which are not part of previous cognitive schemas may separate from consciousness, and non-integrated fragments and events may become conscious later on. We could have access to these fragments (memories, feelings and actions) more easily in situations similar to those that caused trauma.

In order to access the fragments or "subconscious fixed ideas", Janet used hypnosis. He called "psychological automatisms" a great number of elemental structures of specific content combined with perception and action. Many of those psychological automatisms are unified in the consciousness. In stressful times, they could work on its own and independently from consciousness and voluntary control. This is what Janet defined as dissociation. He considered that it occurs as a response to stress, even though some people might be predisposed to develop these dissociative disorders (Janet, 1907).

Something worth mentioning in the beginning of the history of dissociative disorders, is Freud' emphasis in dissociation and traumatic experiences in childhood, and also the opportunity that the Wold Wars and Vietnam War offered to study the relationship between trauma, dissociation and psychiatric morbility. Interest in dissociative processes has been increasing since 1970. Hilgard studied the triggering conditions for these processes in 1977 (Hilgard, 1977). Shortly afterwards, the post-traumatic stress disorder (pTSD) and the consequences of childhood abuse, were associated to dissociative disorders (Atchison & McFarlane, 1994).

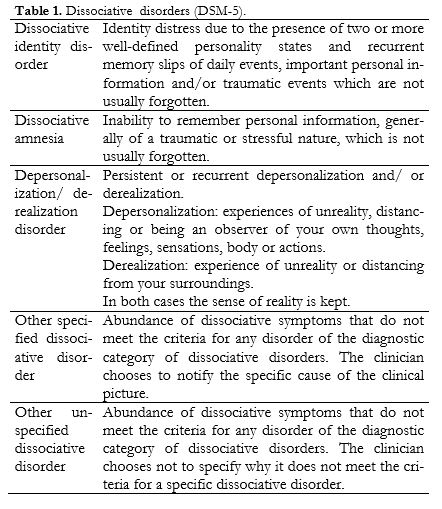

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (2014), states that interruption and/or discontinuity in the normal integration of consciousness, memory, self-identity and subjective identity, emotion, perception, body identity, motor control and behaviour are essential characteristics of dissociative disorders. Alterations can be sudden or gradual, transitory or chronic. The manual classifies the disorders of Table 1, where, in all cases, the disorder causes clinically significant discomfort or any kind of deterioration, whether it be social, at work or in any other area.

Dissociative symptoms can be found in other disorders such as acute stress, posttraumatic stress disorder and somatization disorder. Dissociative disorders are in the DSM-5 between disorder caused by trauma and stress factors and the new category of somatic symptoms disorders and related disorders.

This new category replaces somatomorphic disorders of DSM-IV, due to the superposition between them and the lack of clarity in the line between diagnostics (DSM-5).

In other classifications the conversion reaction is considered a dissociative symptom, but in the DSM-5 it is included in the somatic symptom disorders, thus emphasizing the differences between mental disorder and medical diagnostic. That is, somatic symptoms where it is possible to prove they are not congruent with any medical physiopathology (Spiegel, Lewis-Fernandez, Lanius, Vermetten, Simeon & Friedman, 2013).

In spite of the changes in the DSM-5, there is a lack of unanimous consensus regarding the diagnostic classification of dissociative disorders, especially dissociative amnesia and dissociative identity disorder (pope, Oliva, Hudson, Bodkin & Bruber, 1999). However, the relationship between depersonalization disorder and symptoms of derealisation and other mental disorders such as anxiety that suggest possible common pathophysiology and/or etiologic factors (Hunter, Sierra & David, 2004) are included in the depersonalization-derealisation disorder.

Epidemiologic studies of dissociation have been based on the prevalence of dissociative experiences and psychiatric disorders, multiple personality and prevalence of dissociative disorders in the general population (Atchison & McFarlane, 1994). Some of the scales used for these studies were: Dissociative Experiences Scale; Questionnaire of Experiences of Dissociation; Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Dissociative Disorders; Traumatic Experiences Questionnaire. They evaluate acute dissociative phenomena as a response for traumatic events.

Higher scores, that imply a predisposition for dissociative phenomena, belong to subjects with PTSD, food disorders, phobic disorders and borderline personality disorder among others. Prevalence is approximately of 21% in the clinical population, and between 5% and 10% in general population (Ross, Joshi & Currie, 1990).

There was a rise in the prevalence of dissociative amnesia and dissociative identity disorder in the USA in 1990. It was attributed to forgotten childhood trauma.

Thus, the dissociative symptomatology was considered part of a complex syndrome associated to a traumatic childhood history (Middleton & Butler, 1998) and the degree of somatization and dissociation was associated to childhood trauma (Nijenhuis, Spinhoven, van Dyck, van der Hart & Vanderlinden, 1998). The prevalence of dissociative identity disorder is around 1.5% (DSM-5).

The dissociative fugue disorder presents a prevalence of 0.2% in general population. It may increase in war time or in case of a natural disaster. The dissociative amnesia presents a prevalence of 1.8% (DSM-5). Depersonalisation prevalence is of 2.4% (Ross, 1991). Other studies estimate depersonalization and derealisation to be between 1% and 2% (Hunter, Sierra & David, 2004).

Dissociative disorders are very common in the clinical population, though they are not usually diagnosed. Its high prevalence (up to21%) may be due to methodologic and epidemiologic factors, such as certain sensitive interviews that may lead to bias, or such as high rates of sexual and childhood abuse (Foote, Smolin, Kaplan, Legatt, & Lipschitz, 2006). In general, we speak of dissociative disorders prevalence of 2.4% in developed countries (Deville, Moeglin & Sentissis, 2014).

Multiple personality disorder (dissociative identity disorder)

Explicative theories of the multiple personality disorder (MPD) have been synchronized to the psychological theories of their time. They ranged from the supernatural, possessions or reincarnations to the cerebral hemispheres disconnection syndrome. The theoretical formulations for the MPD started in the 19th century, with Charcot and Janet, and later on, Prince, Freud and Breuer would elaborate on it. MPD was included in the hysteria section of the DSM-I. Its characteristics were described in the DSM-III-R. Kluf (1987) tried to adapt the available data about MPD to clinical needs. He proposed an etiologic model that included four elements: factors of predisposition, a traumatic experience, cognitive processes involved and inappropriate retroactive experiences that make impossible an integrated experience.

From its initial formulations, MPD theories have been associated with hypnosis and the experience of a trauma (putnam, 2009). However, neither physiologic nor psychological studies give a clear and conclusive definition of the disorder.

The varied symptoms of MPD inevitably entail error in diagnosis and in the choice of treatment many times. It is no wonder there is scepticism about MPD, supported by the concepts of false memories and personality. Hypotheses that emphasize different degrees of integration and identity implied in the term "personality" are thought to be more acceptable. Thus, it is possible that MPD patients show noticeable differences in mental states, rather than whole, independent personalities (Kirsch & Lynn, 1998).

MPD distinctive characteristics are: appearance before the age of 12, associated trauma due to abuse, predominance in female population and chronic course (Doan & Bryson, 1994). Even though there is certain evidence suggesting dissociative behaviour might be, to some extent, biologically determined, there is no reference model to study the biological mechanisms that may be involved. Generally, specific biological and environmental conditions are deemed necessary in order to develop a dissociative experience, such as physical or psychological abuse or extreme discipline and punishment in childhood.

One of the triggering factors most cited in the literature is the trauma, conceived as the cause of psychic damage, usually from sexual abuse and incest. MPD maintenance factors are lacking in the same way its etiology does. This is due to the disorder's heterogeneity. Regarding dissociation as an instrumental resource, it does not seem to change the patients' circumstances. However, environmental influences, attitudes, even the efforts to hide the disorder can act as maintenance factors, in addition to some other symptoms. The main factor may be the dissociative capability in itself (Kluft, 1987).

Studies on the treatment and monitoring of MPD are few, though there are some guides based on clinical experience. They are generally based on intensive individual psychotherapy and achieving a therapeutic alliance with each of the multiple personalities. As for attendance, the generalized opinion between professionals is that MPD patients must be treated in outpatient regimen (putnam & Loewenstein, 1993). The long duration of the treatment and the limited hospital resources make the inpatient regimen almost impossible in current times. Nevertheless, it is not rare for MPD patients to be hospitalized because of suicidal impulses, suicide attempts, depression and violent behaviour. Patients are characterized by instability and vulnerability alternated with apparent normality (Irpati, Avasthi & Sharan, 2006). These fluctuations in behaviour and changes of personality are characteristic of MPD. They are diagnostic indicators of the disorder. Diagnostic certainty is crucial in order to make appropriate interventions and to study the convenience of hospitalization.

Patients can experience insecurity and a sense of danger during treatment in an acute crisis. They may think they are not being helped. The necessary assistance and care can be provided by a hospital, thus the need of specialization for these patients (Kluft, 1991). Once the patient is hospitalized starts a process of continuous care. That should make the patient feel safe and supported. However, hospitalization can entail several problems for the patient and the clinical staff. The patient may believe he is possessed, he may try to get privileges or coerce other patients (Kluft, 2001). The treatment usually consists of different phases, depending on the objectives. Table 2 shows an adapted summary of the phases of treatment (Kluft, 1991).

The length of the hospitalization will depend on the objectives of the treatment (Kluft, 2001). A certain amount of time is needed to establish a safe, trusting and supporting environment in order to start the treatment (Kreidler, Zupancic, Bell & Longo, 2000). General measures include anticipating diagnosis, delimiting the surroundings of the treatment space and practicing team interventions. There are some rules regarding patients as well: they must be told the rules of their stay, their legal name must be used, and the reasons for those two rules must be told to the staff and the patients, patients should have individual rooms when possible, they must be explained that the staff is under no obligation of recognising the different personalities and behaviours. It is crucial to consolidate the therapeutic alliance with the patient. The tasks of each member of the team and the patient must be defined (Kluft, 1984). The combination of psychodynamic psychotherapy and hypnotic intervention is frequent (Kluft, 2003).

Hysteria and Multiple Personality

Hysteria is understood as a heterogeneous manifestation in which three disorders or states are differentiated: hysterical personality (not necessarily pathologic), hysterical conversion and chronic hysteria. This term was taken away from DSM-III, and it is known as dissociative disorder (of conversion) in modern psychiatric classifications in the CIE-10; and as dissociative disorders and conversion disorders in somatomorphic disorders of DSM-IV. Some authors suggest the reclassification of this group of conversion disorders in the group of dissociative disorders (Brown, Cardena, Nijenhuis, Sar & van der Hart, 2007). They are included in the diagnostic category of trauma and stress factor- related disorders in the DSM-5.

Hysteria has been traditionally linked with the dysfunction of the right hemisphere. Chronic hysteria and MPD are differentiated by an opposed cerebral hemisphere electroencephalographic activation, manifested by a suppression of the alpha rhythm. The relative activation of the right hemisphere in hysteria and left hemisphere in the MPD could explain these disorders (Flor-Henry, 1994).

Under this premise, conscious experience is a dependent function of a critical neural system known as axis of consciousness. Multiple personality is a different state dependent of learning, where amnesia isolates a particular affective state, (supposedly controlled by the right hemisphere), blocking the conscious experience (supposedly controlled by the left hemisphere) (Flor-Henry, Tomer, Kumpula, Koles, & Yeudall, 1990).

In experimental studies with animals, prolonged stress leads to hippocampus necrosis as a result of the excess of adrenal glucocorticosteroids. Prolonged severe stress due to physical torture or sexual abuse was observed in the history of women with multiple personality syndrome. It could cause an inhibitory dysfunction of the hippocampus. Under these stressful situations, the hypothalamic- pituitary- adrenal axis is unbalanced, which causes somesthetic, gastrointestinal and autonomous system alterations. If alterations were to happen regularly, they could provoke a series of physical symptoms associated to emotional disorders, which is known as hysteria.

Tonsils and hypothalamus regulate the emotional conduct of fear. They both affect males and females differently. Chronical hysteria affects women in particular. Neuropsychological studies show that women's bilateral cerebral dysfunction (frontotemporal) presents a higher dysfunction of the right hemisphere when compared to subjects with healthy control (Flor-Henry, Fromm-Auch, Tapper & Schopflocher, 1981). In studies of suggestibility, there are significative differences between genders. Women scored higher average rates than men (Gonzalez-Ordi & Miguel-Tobal, 1999).

Post-traumatic stress disorder

While Janet places dissociation in traumatic events, Spiegel (1991) claims it is fundamental in post-traumatic stress disorder (pTSD). Dissociation can be seen as a normal response to a traumatic event. Two theoretical approaches can be taken to explain dissociation in PTSD. The first approach assumes that dissociation happens in order to solve a conflict, even though it could hardly do it. Dissociation has a disruptive character. It is clearly seen in the interferences it causes in individual adaptation, specially memory, in daily life situations.

The second approach focuses on information processing. It assumes that stress rises arousal and decreases information processing, memory processes specifically. Thus, dissociation can occur because an excess of attentional demand causes a loss of control of cognitive resources. However, not all PTSD patients present dissociation at the time of the trauma, nor do they manifest dissociative characteristics because of their disorder. This implies a certain vulnerability or predisposition to dissociation in PTSD patients. On the other hand, repeated or prolonged stressful situations may require the subject to use extreme adaptation measures through dissociation in order to reduce stress. Two PTSD types can be then differentiated: one with predominantly dissociative symptoms during a traumatic event, and other with predominantly anxiety symptoms (Atchison & McFarlane, 1994). Even then, the revision of diagnosis criteria should be based in empiric evidence from people subjected to stress. Appropriate differential diagnosis between PTSD and other anxiety disorders can be made based on this. Acute stress disorder (Bryant & Harey, 1997), or brief reactive dissociative disorder, for example. Brief reactive dissociative disorder was proposed by Spiegel, Cardena and Spitzer (1989). It includes dissociative disorders with an anxious reaction to a more than a month-long stressful event. Unlike PTSD, they focus on the contribution of the dissociative process to posttraumatic symptomatology. Brief reactive dissociative disorder was not included in DSM-IV (Spiegel & Cardena, 1991).

Suicide and dissociation

Subjects with suicidal tendencies present a predisposition to dissociation, pain insensitivity and indifference towards the body. If we understand dissociation as a separation of conscious experience, two main dissociative processes may occur: separation, loss or limitation of experience, and loss of control (the capability to monitor behaviour).

Several theoretical and experimental studies (Orbach, 1994) suggest that stressful conditions lead to the development of dissociative tendencies. Once established, they are part of suicidal behaviour.

Subjects with suicidal predisposition may present a high pain tolerance, increased by several psychological factors. People who opt for violent and painful suicide methods may present this predisposition to dissociation related to indifference towards the state of the body and pain insensitivity under severe stress.

There has been research about animal defence reaction as a trauma-induced dissociative reaction model. Research, empirical data and observation of clinical patients show similarities between paralysis, analgesia and anaesthesia with the acute pain in the treatment of animals and people subjected to a grave trauma (Vanderlinden & Spinhoven, 1998; Crawford et al., 1999).

Determined suicidal behaviours in teenagers can result from a complicated familiar dynamic. Dissociative processes can offer coping strategies in those circumstances. That is, in a case of abuse, the chosen way to face familiar conflict is to separate behaviour, emotions and cognitions. This separation will create two behavioural patterns representative of different substructures of the subject. This implies different ways of perceiving the world and oneself.

In patients with grave dissociative disorders, somatization and suicidal ideation are frequently associated. In these cases, common symptoms refer an insecure attachment pattern and a history of childhood trauma (Ozturk & Sar, 2008). Outpatients diagnosed with substance abuse, PTSD or intermittent explosive disorder, with high scores in dissociative tests, can be a group at risk of self-harm behaviour (Zlotnick, Mattia & Zimmerman, 1999).

Hypnosis and dissociation

The idea that hypnotic behaviour is due to a division of consciousness in two or more parts is nothing new (putnam, 1986). Currently brought back, Hilgard's neodissociation theory (1977) proposes that hypnotic phenomena are dissociative processes. Hypnotic responses have been attributed to two basically dissociative mechanisms: a division of consciousness in two groups separated by a mnesic barrier limiting the access of executive function, control function or both. In dissociative control theory, hypnotic suggestion is characterized by a weakening of the control over frontal lobules, specifically behaviour outlines. This allows the activation of the hypnosis-induced behaviour (Kirsch & Lynn, 1998). From these theories, it is deduced that hypnosis can be an appropriate treatment for PTSD (Cardeñas, Maldonado, Galdón & Spiegel, 1999).

Both theories assume that behaviour is organized in a hierarchical system of response control mechanisms. Different subsystems are controlled by a central system or executive. Its function is to initiate action sequences and monitor consequences. In dissociative control theory, control subsystems can be directly and automatically activated, with no intervention of the executive system. According to dissociative control theory, when a subsystem is activated by suggestion, cognitive effort must be lower than the effort of intentional activation. In neodissociation theory, responses, intentional acts, entail keeping control over consciousness (awareness). They require cognitive effort, and interferences can occur between two tasks, but mnesic barriers can compensate it. In order to establish the experimental basis of these theories, two hidden observer studies, divided attention studies and hypnosis-induced amnesia studies were used. There is few evidence to support any of the theories, and both face conceptual difficulties. Other theories propose that hypnotic behaviour is the result of attentional functions, specifically inhibitory functions. But, like the former theories, there is little empiric evidence. In a recent study, associations between hypnotic suggestion, dissociation and cognitive inhibition were examined. No significant correlations between the scores of resistance to hypnotic suggestion, dissociation and general cognitive inhibition were found, except for some gender differences (Dienes, 2009).

Current Outlook

Dissociative disorders consist of a group of syndromes with the common factor of being a consciousness disorder manifested in memory and identity alterations (Kihlstrom et al., 1994). Consciousness is a continuum, so there is a blurred line separating normal and pathological dissociation. Information and dissociated processes can interfere and cause a priming effect in the performance of different tasks (Kihlstrom & Hoyt, 1990). In these cases, even if dissociated information is not available to consciousness, it can influence conscious behaviour by altering it. Therefore, it seems the concept of dissociation does not require complete independence of the elements involved (Spiegel & Cardeña, 1991). Extreme traumatic experiences can nullify part of consciousness and allow the subject to keep working with other parts (Ludwig, 1990). Dissociation also presents different characteristics in different subjects (Stolovy, Lev-Wiesel & Witzum, 2014).

The idea of dissociation still presents conceptual differences. They are partially reflected in the classification of these disorders in CIE-10 and DSM-5. Some approaches qualitatively subdivide dissociation in different groups such as pathologic and non- pathologic (Holmes et al., 2005; Spitzer, Barnow, Freyberger & Grabe, 2006). Not all researches point in the same direction (Browns et al., 2007; Espirito-Santo & Pio-Abreu, 2009). We shall have to wait for the classification of symptoms of dissociation and conversion disorders in CIE-11.

Even though dissociation implies cognitive processes, neuropsychological studies have been few. There are researches on the relation between executive functions and mental disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression (Elvevag & Goldberg, 2000; Quraishi, & Frangou, 2002; Sharma & Antonova, 2003; Roger et al., 2004). In most of them, patients suffering from any of the mental disorders are said to present alterations in their executive function. However, the relationship between executive function and dissociation has been practically omitted. The results of the few recent studies are contradictory (Bruce, Ray, Bruce, Arnett & Carlson, 2007). On the one hand, it seems that frontal deficits contribute to the development of dissociative alterations (Cima et al, 2001). They study the way executive alterations are associated to dissociative pathological aspects (Giesbrecht, Merckelbach, Geraert, & Smeets, 2004). On the other hand, no differences are found in the records for executive functions, when comparing subjects with high and low scores in dissociation. However, those with high scores in dissociation present more problems with executive control. Even so, self-perception of efficiency and test performance do seem to be dissociated (Bruce et al., 2007).

Professionals agree to consider memory alterations as basic symptoms in the clinical observation of dissociative processes. Emotional processing or attentional functions are other associated cognitive processes.

Some models have been proposed in order to combine cognitive processes with traumatic events. Dissociative phenomena require memory and learning cognitive processes that take a lot of effort. The models explain how, in nonpathological conditions, subjects can profit from dissociative capability (which could become pathological due to traumatic events) (de Ruiter et al., 2006). Processing speed decrease (measured in neuropsychological tests) in women with PTSD due to abuse, is related to gravity of the symptoms. It might be a sign of the need to reassign resources to face the sources of stress (Giesbrecht, Lynn, Lilienfeld & Mereckelbach, 2008; Twamley et al., 2009).

Ever since its appearance in 1980, PTSD has been understood as a mental response to a trauma. Because of that, it has been set aside from biopathological investigations. It has prejudiced the patients who may not be receiving appropriate attention (McHugh & Treisman, 2007). However, the study of PTSD neurobiological basis is shedding light on the disorder, and encouraging the investigation of new treatments, specially pharmacological (Maia & Costa-Oliveira, 2010; Lanius, Brand, Vermetten, Frewen & Spiegel, 2012). PTSD cannot be understood without the social context where it happens (Auxéméry, 2012). Its essential characteristic is the development of specific symptoms after one or more traumatic events. Emotional responses to the traumatic event do not play a main role anymore. Furthermore, cognitive or behavioural symptoms, or a combination of both, can take preference in PTSD clinical presentation.

Programs specialized in the treatment of dissociative identity disorder would offer obvious benefits. Qualified staffs, specific services, improvement in care and safety for the patient and appropriate anxiety management and control are some of them (Kluft, 2001). However, the advances achieved in treatments have often been shaded by controversy surrounding PTSD (Kluft, 2003). There are methodological limitations in current research as well, specifically in the results of dissociative disorders treatment. They affect internal and external validity, for example with limited sample sizes and non-random design (Brand, Classen, McNary & Zaveri, 2009). Depersonalization-derealisation dissociative disorder has few prevalence data supporting new epidemiologic studies. The study of clinical cases supports a combination of psychotherapy and pharmacological treatment integrated in longer, multidisciplinary interventions (Gentile, Snyder & Gillig, 2014).

Regarding the relationship between dissociative disorders and pain and suicide, new lines of investigation focus on factors associated to suicidal behaviour. Rather than seeing suicidal behaviour as a cause, there is a preventive purpose (Orbach, 1994). It is named in DSM-5, specifically in the diagnosis of PTSD, dissociative identity disorder and dissociative amnesia.

In research about hypnosis and its relation to age, there is a curve relationship between 8-13 years and hypnotic suggestion (Cooper & London, 1971). In that period there is a greater potential for developing dissociative skills. Thus, any traumatic event can be partially integrated and dissociated. It can become an underlying factor for a future dissociative disorder. Dissociative processes and grave traumas seem to be linked to the development of some characteristics of personality disorder and dissociative disorder (Atchison & McFarlane, 1994; Bru, Santamaría, Coronas & Cobo, 2009). Adult patients, often find the cause of their disorder in childhood traumatic experiences, specially in the case of dissociative identity disorder. However, the relationship of causality between trauma and dissociation is not empirically justified (Giesbrecht & Merckelbach, 2005). Dissociation and hypnotic phenomena are not identical phenomena, though they share some similarities. There is little empiric evidence to prove a relationship between them both. Hypothesis posed to explain hypnosis with dissociative phenomena included consciousness division and a state of decrease of attentional control (Kirsch & Lynn, 1998) but they are met with scepticism. These results pose a serious challenge for current hypnosis theories (Dienes et al., 2009).

Dissociative disorders raise interesting questions about identity, the role of conscience and autobiographic memory in the continuum of personality. Clinical and experimental studies on dissociative processes of cognitive, emotional and behavioural functions are being implemented. Investigations on attentional and memory functions, personality traits and hypnotic suggestion are using them, for example (Gruzeiler, 1999). Neuroimaging data, combined with biological studies (specially endocrine) must be anatomically and functionally integrated, new approaches say. Thus, specific neurobiological models can be developed; taking into account that dissociative disorder treatment depends on concurrent disorders (Damsa, Lazignac, Pirrotta & Andreoli, 2006). It can mean many benefits in interventions. Exposure treatment could be recommended for PTSD and depressive disorder patients, for example (Hagenaars, van Minnen & Hoogduin, 2010). In neuroimaging tests, the size of tonsils and hippocampus has been associated to cognitive deficits linked to PTSD, but not dissociative amnesia or MPD (Weniger, Lange, Sachsse & Irle, 2008). Research with neuroimaging enriches our knowledge of disorder etiology. Neuroimaging allows us to identify different patient groups, so its effect in diagnostic and treatment is promising (García-Campayo, Fayed, Serrano-Blanco & Roca, 2009; Deeley et al., 2014). This and the new epidemiologic studies are improving our knowledge on dissociative disorders (Stein et al., 2013).

Conclusions

We have examined dissociative phenomena studies and their relationship to psychopathology from the last decade of the 20th century to the first decade of the 21st century. Judging from those investigations, it seems that our knowledge of dissociative phenomena and disorders has not improved since Janet's systematic study (1889). Nevertheless, it can also be deduced that, in order to understand and treat dissociation, models connecting personality, psychopathology and neurobiology are needed. In the last decades there has been a huge progress in neuroscience. Yet, we still know very little about dissociative phenomena and disorder, maybe because they involve consciousness. New investigations (with a greater methodological rigour) in the field of neuroscience are needed. Neuropsychological studies working with neuroimaging techniques can shed light on these phenomena. DSM-5 already reflected this and CIE 11 cannot omit it.

References

1. American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Text revised. Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Association. [ Links ]

2. Asociación Americana de Psiquiatría. (2014). Manual diagnóstico y estadístico de los trastornos mentales (DSM-5), 5a Ed. Arlington (VA): Asociación Americana de Psiquiatría. [ Links ]

3. Atchison , M., & McFarlane, A. C. (1994). A review of dissociation and dissociative disorders. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 28, 591-599. doi: 10.3109/00048679409080782. [ Links ]

4. Auxéméry, Y. (2012). Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a consequence of the interaction between an individual genetic susceptibility, a traumatogenic event and a social context. Encephale, 5, 373-380. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2011.12.003. [ Links ]

5. Brand, B. L., Classen, C. C., McNary, S. W., & Zaveri, P. (2009). A review of dissociative disorders treatment studies. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 197, 646-654. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181b3afaa. [ Links ]

6. Brown, R. J., Cardeña, E., Nijenhuis, E. Sar, V., & van der Hart, O. (2007). Should conversion disorder be reclassified as a dissociative disorder in DSM V? Pychosomatics, 48, 369-378. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.48.5.369. [ Links ]

7. Bru, M., Santamaría, M., Coronas, R. y Cobo, J. V. (2009). Trastorno disociativo y acontecimientos traumáticos. Un estudio en población española. Actas Españolas de Psiquiatría, 37, 200-204. Recuperado de http://actaspsiquiatria.es/repositorio/10/58/ESP/14143+4.+1174+esp.pdf. [ Links ]

8. Bruce, A. S., Ray, W. J., Bruce, J. M. Arnett, P. A., & Carlson, R. A. (2007) The relationship between executive functioning and dissociation. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 29, 626-633. [ Links ]

9. Bryant, R. A., & Harvey, A. G. (1997). Acute stress disorder: a critical review of diagnostic issues. Clinical Psychology Review, 17, 757-773. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(97)00052-4. [ Links ]

10. Cardeña, E., Maldonado, J., Galdón, M. J. y Spiegel, D. (1999). La hipnosis y los trastornos postraumáticos. Anales de Psicología, 15, 147-155. Recuperado de http://www.um.es/analesps/v15/v15_1pdf/13h10carde.pdf. [ Links ]

11. Cima, M., Merckelbach, H., Klein, B., Schellbach-Matties, R., & Kremer, K. (2001). Frontal lobe dysfunctions, dissociation, and trauma self-reports in forensic psychiatric patients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 189, 188-190. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200103000-00008. [ Links ]

12. Cooper L. M., & London, P. (1971). The development of hypnotic susceptibility: A longitudinal (convergence) study. Child Development, 42, 487-503. doi: 10.2307/1127482. [ Links ]

13. Crawford, H. J., Knebel, T., Vendemia J. M. C., Horton, J. E. y Lamas, J. R. (1999). La naturaleza de la analgesia hipnótica: Bases y evidencias neurofisiológicas. Anales de Psicología, 15, 133-146. Recuperado de http://www.um.es/analesps/v15/v15_1pdf/12h05Craw.pdf. [ Links ]

14. Damsa, C., Lazignac, C., Pirrotta, R., & Andreoli, A. (2006). Dissociative disorders: clinical, neurobiological and therapeutical approaches. Revue Médicale Suisse, 8, 400-405. [ Links ]

15. de Ruiter, M. B., Elzinga, B. M., & Phaf, R. H. (2006). Dissociation: cognitive capacity or dysfunction?. Journal of Trauma and Dissociation, 7, 115-134. doi 10.1300/229v07n04_07. [ Links ]

16. Deeley, Q., Oakley, D. A., Walsh, E., Bell, V., Mehta, M. A., & Halligan, P. W. (2014). Modelling psychiatric and cultural possession phenomena with suggestion and fMRI. Cortex, 53, 107-119. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2014.01.004. [ Links ]

17. Devillé, C., Moeglin, C., & Sentissi, O. (2014). Dissociative Disorders: Between Neurosis and Psychosis. Case Report in Psychiatry, doi: 10.1155/2014/425892. [ Links ]

18. Dienes, Z., Brown, E., Hutton, S., Kirsch, I., Mazzoni, G., & Wright, D. B. (2009) Hypnotic suggestibility, cognitive inhibition, and dissociation. Consciousness and Cognition, 18, 837-847. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2009.07.009. [ Links ]

19. Doan, B. D., & Bryson S. E. (1994). Etiological and maintaining factor in multiple personality disorder: a critical review. En R. M. Klein y B. K. Doane (Eds.), Psychological Concepts and Dissociative Disorders (pp. 51-84). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc. [ Links ]

20. Elvevag, B., & Goldberg, T. E. (2000). Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia is the core of the disorder. Critical Reviews in Neurobiology, 14, 1-21. doi: 10.1615/CritRevNeurobiol.v14.i1.10. [ Links ]

21. Espirito-Santo, H., & Pio-Abreu, J. L. (2009) Psychiatric symptoms and dissociation in conversion, somatization and dissociative disorders. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 43, 270-276. doi: 10.1080/00048670802653307. [ Links ]

22. Flor-Henry, P. (1994). Cerebral Aspect of hysteria and Multiple Personality. En R. M. Klein & B. K. Doane (Eds.), Psychological Concepts and Dissociative Disorders (pp. 237-258). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc. [ Links ]

23. Flor-Henry, P., Fromm-Auch, D., Tapper, M. & Schopflocher, D. (1981). A neuropsychological study of the stable syndrome of hysteria. Biological Psychiatry, 16, 601-616. [ Links ]

24. Flor-Henry, P., Tomer, R., Kumpula, I., Koles, Z. J., & Yeudall, L. T. (1990). Neurophysiological and neuropsychological study of two cases of multiple personality syndrome and comparison with chronic hysteria. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 10, 151-161. [ Links ]

25. Foote, B., Smolin, Y., Kaplan, M., Legatt, M. E., & Lipschitz, D. (2006). Prevalence of dissociative disorders in psychiatric outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163, 623-629. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.623. [ Links ]

26. García-Campayo, J., Fayed, N., Serrano-Blanco, A., & Roca, M. (2009). Brain dysfunction behind functional symptoms: neuroimaging and somatoform, conversive, and dissociative disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 22, 224-231. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283252d43. [ Links ]

27. Gentile, J. P., Snyder, M., & Gillig, P. (2014). Stress and Trauma: Psychotherapy and Pharmacotherapy for Depersonalization/Derealization Disorder. Innovation in Clinical Neuroscience, 11, 37-41. Recuperado de http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4204471/. [ Links ]

28. Giesbrecht, T., & Merckelbach, H. (2005). The causal relation between dissociation and trauma. A critical overview. Der Nervenarzt, 76, 20-27. Recuperado de http://arnop.unimaas.nl/show.cgi?fid=2405. [ Links ]

29. Giesbrecht, T., Lynn, S. J., Lilienfeld, S. O., & Merckelbach, H. (2008). Cognitive processes in dissociation: an analysis of core theoretical assumptions. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 617-647. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.5.617. [ Links ]

30. Giesbrecht, T., Merckelbach, H., Geraerts, E., & Smeets, E. (2004). Dissociation in undergraduate students: Disruptions in executive functioning. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 192, 567-569. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000135572.45899.f2. [ Links ]

31. González-Ordi, H. y Miguel-Tobal, J. J. (1999). Características de la sugestionabilidad y su relación con otras variables psicológicas. Anales de Psicología, 15, 57-75. Recuperado de http://www.um.es/analesps/v15/v15_1pdf/07h01hect.pdf. [ Links ]

32. Gruzelier, J. (1999). La hipnosis desde una perspectiva neurobiológica: Una revisión de la evidencia y aplicaciones a la mejora de la función inmune. Anales de Psicología, 15, 111-132. Recuperado de http://revistas.um.es/analesps/article/view/31191. [ Links ]

33. Hagenaars, M. A., van Minnen, A., & Hoogduin, K. A. L. (2010). The impact of dissociation and depression on the efficacy of prolonged exposure treatment for PTSD. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48, 19-27. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2009.09.001. [ Links ]

34. Hilgard, E. R. (1977). Divided consciousness: Multiple controls in human thought and action. New York: Wiley. [ Links ]

35. Holland, J. C. (1989). Fears and Abnormal reactions to cancer in physically healthy individuals. En J.C. Holland, & J.H. Rowland (Eds.), Handbook of Psychooncology (pp. 13-21). New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

36. Holmes, E. A., Brown, R. J., Mansell, W., Fearon, R. P., Hunter, E. C. M., Frasquilho, F., & Oakley, D. A. (2005). Are there two qualitatively distinct forms of dissociation? A review and some clinical implications. Clinical Psychology Review, 25, 1-23. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.08.006. [ Links ]

37. Hunter, E. C., Sierra, M., & David, A. S. (2004). The epidemiology of depersonalisation and derealisation. A systematic review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 39, 9-18. [ Links ]

38. Irpati, A. S., Avasthi, A., & Sharan, P. (2006). Study of stress and vulnerability in patients with somatoform and dissociative disorders in a psychiatric clinic in North India. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 60, 570-574. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2006.01560.x. [ Links ]

39. Janet, P. (1889). L'automatisme psychologique. Paris: Felix Alcan. [ Links ]

40. Janet, P. (1907). The mayor symptoms of hysteria. New York: MacMillan. [ Links ]

41. Kihlstrom, J. E., & Hoyt, I. P. (1990). Repression, dissociation, and hypnosis. En J. L. Singer (Ed.), Repression and dissociation (pp. 181-208). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

42. Kihlstrom, J. F., Glisky, M. L., & Angiulo, M. J. (1994). Dissociative tendencies and dissociative disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 102, 117-124. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.103.1.117. [ Links ]

43. Kirsch, I., & Lynn, S. J. (1998). Dissociation theories of Hypnosis. Psychological Bulletin, 123, 100-115. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.123.1.100. [ Links ]

44. Kluft, R. P. (1984). Aspects of treatment of multiple personality disorder. Psychistric Annals, 14, 51-55. doi: 10.3928/0048-5713-19840101-09. [ Links ]

45. Kluft, R. P. (1987). An update on multiple personality disorder. Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 38, 363-373. doi: 10.1176/ps.38.4.363. [ Links ]

46. Kluft, R. P. (1991). Hospital treatment of multiple personality disorder: An Overview. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 14, 695-719. [ Links ]

47. Kluft, R. P. (2001). The difficult to treat patient with dissociative disorders. En M. J. Dewan, & R.W. Pies (Eds.), The difficult-to-treat psychiatric patient (pp. 209-242). Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing Inc. [ Links ]

48. Kluft, R. P. (2003). Current issues in dissociative identity disorder. Bridging Eastern and Western Psychiatry, 1, 71-87. doi: 10.1097/00131746-199901000-00001. [ Links ]

49. Kreidler, M. C., Zupancic, M. K., Bell, C., & Longo, M. B. (2000). Trauma and dissociation: Treatment perspectives. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 36, 77-85. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2000.tb00697.x. [ Links ]

50. Lanius, R. A., Brand, B., Vermetten, E., Frewen, P. A., & Spiegel, D. (2012). The dissociative subtype of posttraumatic stress disorder: rationale, clinical and neurobiological evidence, and implications. Depression and Anxiety, 29, 701-708. doi: 10.1002/da.21889. [ Links ]

51. Luwdig, A. M. (1990). The Psychobiological functions of dissociation. American Journal of Clinical Hypnotherapy, 26, 93-99. doi: 10.1080/00029157.1983.10404149. [ Links ]

52. Maia, L. A. C. R., & Costa-Oliveira, J. M. (2010). Bases neurobiológicas del estrés post-traumático. Anales de Psicología, 26, 1-10. doi: 10.6018/91891. [ Links ]

53. McHugh, P. R., & Treisman G. (2007). PTSD: a problematic diagnostic category. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 21, 211-222. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.09.003. [ Links ]

54. Middleton, W., & Butler, J. (1998). Dissociative identity disorder: An Australian series. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatr, 32, 794-804. doi: 10.3109/00048679809073868. [ Links ]

55. Nijenhuis, E. R. S., Vanderlinden, J., & Spinhoven P. (1998). Animal defensive reactions as model for trauma-induced dissociative reactions. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 11, 243-260. doi: 10.1023/A:1024447003022. [ Links ]

56. Nijenhuis, E. R., Spinhoven, P., van Dyck, R., van der Hart, O., & Vanderlinden, J. (1998). Degree of somatoform and psychological dissociation in dissociative disorder is correlated with reported trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 11, 711-730. doi: 10.1023/A:1024493332751. [ Links ]

57. Orbach, I. (1994). Dissociation, physical pain, and suicide: A hypothesis. Suicide and life-threatening behavior, 24, 68-79. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.1994.tb00664.x. [ Links ]

58. Oztürk, E., & Sar., V. (2008). Somatization as a predictor of suicidal ideation in dissociative disorders. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 62, 662-668. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2008.01865.x. [ Links ]

59. Pope, H. G., Oliva, P. S., Hudson, J. I., Bodkin, J. A., & Bruber, A. J. (1999). Attitudes toward DSM-IV dissociative disorders diagnoses among board-certified American psychiatrists. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156, 321-323. Recuperado de http://psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/ajp.156.2.321. [ Links ]

60. Putnam, F. W. (1986). The scientific investigation of multiple personality disorder. En J. M. Quen (Ed.). Split Mind Split Brain (pp.109-126). New York: New York University Press. [ Links ]

61. Putnam, F. W. (1989). Pierre Janet and modern views of dissociation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 2, 413-429. doi: 10.1007/BF00974599. [ Links ]

62. Putnam, F. W. (2009). Take the measure of dissociation. Journal of trauma and dissociation (10), 233-236. doi: 10.1080/15299730902956564. [ Links ]

63. Putnam, F. W., & Loewenstein, R. J. (1993). Treatment of multiple personality disorder: a survey of current practices. American Journal of Psychistry, 150 (7), 1048-1052. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.7.1048. [ Links ]

64. Quraishi, S., & Frangou, S. (2002). Neuropsychology of bipolar disorder: A review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 72, 209-226. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00091-5. [ Links ]

65. Rayner, K., & Pollatsek, A. (1989). The psychology of reading. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

66. Rogers, M. A., Kasai, K., Koji, M., Fukuda, R.,Iwanami, A., Nakagome, K., Fukuda, M., & Kato, N. (2004). Executive and prefrontal dysfunction in unipolar depression: A review of neuropsychological and imaging evidence. Neuroscience Research, 50, 1-11. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2004.05.003. [ Links ]

67. Ross, C. A. (1991) Epidemiology of multiple personality disorder and dissociation. Psychiatric Clinics of North America,14, 503-17. [ Links ]

68. Ross, C. A., Joshi, S., & Currie, R. (1991). Dissociative experiences in the general population. American Journal of Psychiatry, 147, 1547-1552. [ Links ]

69. Sharma, T., & Antonova, E. (2003). Cognition in schizophrenia: Deficits, functional consequences, and future treatments. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 26, 25-40. [ Links ]

70. Spiegel, D., & Cardeña, E. (1991). Disintegrated experience: the dissociative disorders revisited. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100, 366-378. doi: 10.1037//0021-843X.100.3.366. [ Links ]

71. Spiegel, D., Lewis-Fernández, R., Lanuis, R., Vermettern, E., Simeon, D., & Friedman, M. (2013). Dissociative disorders in DSM-5. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 299-326. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185531. [ Links ]

72. Spitzer, C., Barnow, S., Freyberger, H. J., & Grabe, H. J. (2006). Recent developments in the theory of dissociation. World Psychiatry, 5, 2-6. Recuperado de http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1525127/pdf/wpa050082.pdf. [ Links ]

73. Stein, D. J., Koenen, K. C., Friedman, M. J., Hill, E., McLaughlin, K. A., Petukhova, M., ... Kessler, R. C. (2013). Dissociation in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Evidence from the World Mental Health Surveys. Biological Psychiatry, 73(4), 302-312. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.08.022. [ Links ]

74. Stolovy, T., Lev-Wiesel, R., & Witztum, E. (2014). Dissociation: Adjustment or Distress? Dissociative Phenomena, Absorption and Quality of Life Among Israeli Women Who Practice Channeling Compared to Women with Similar Traumatic History. Journal of Religion and Health, 27. doi: 10.1007/s10943-014-9885-4. [ Links ]

75. Twamley, E. W., Allard, C. B., Thorp, S. R., Norman, S. B., Cissell, S. H., Berardi, K. H., Grimes, E. M., & Stein, M . B. (2009). Cognitive impairment and functioning in PTSD related to intimate partner violence. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 15, 879-887. doi: 10.1017/S135561770999049X. [ Links ]

76. Weniger, G., Lange, C., Sachsse, U., & Irle E. (2008). Amygdala and hippocampal volumes and cognition in adult survivors of childhood abuse with dissociative disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 118, 281-290. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01246.x. [ Links ]

77. Zlotnick, C., Mattia, J. I., & Zimmerman, M. (1999). Clinical correlates of self-mutilation in a sample of general psychiatric patients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 187, 296-301. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199905000-00005. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Dr. D. Modesto Jesús Romero López.

Universidad de Huelva.

Departamento de Psicología Clínica, Experimental y Social.

Campus "El Carmen".

Avenida de la Fuerzas Armadas, s/n, 21071,

Huelva (España).

E-mail: modesto.romero@dpsi.uhu.es

Artlculo recibido: 23-01-2015;

Revisado: 23-01-2015;

Aceptado: 09-02-2015