Meu SciELO

Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Anales de Psicología

versão On-line ISSN 1695-2294versão impressa ISSN 0212-9728

Anal. Psicol. vol.33 no.1 Murcia Jan. 2017

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.33.1.225791

The social construction of homoparentality: academia, media, and expert discourse

La construcción social de la homoparentalidad: ámbito académico, medios de comunicación y discurso experto

Laura Domínguez de la Rosa and Francisco Manuel Montalbán Peregrín

Facultad de Estudios Sociales y del Trabajo, Universidad de Málaga (Spain).

ABSTRACT

This study analysed the discursive strategies used to construct the phenomenon of gay and lesbian parenting in different public settings such as academia, the media, and the law. A qualitative research method was used: specifically, discourse analysis based on Potter and Wetherell's proposals concerning interpretive repertoires. It was found that defensive normalisation strategies are favoured against the risk of homophobia and attacks on family diversity.

There is a risk of overlooking resources and experiences that could contribute to a richer collective construction of the phenomenon, reflecting its progress in the legislative, social, and political fields.

Key words: gay and lesbian parenting; qualitative method; normalisation; interpretive repertoires.

RESUMEN

Este trabajo pretende conocer las estrategias discursivas desde las que se está construyendo el fenómeno homoparental en diferentes espacios públicos, como son: el ámbito académico, los medios de comunicación y el ámbito experto profesional-legislativo. El método de investigación que se utiliza es cualitativo, concretamente, el Análisis del Discurso a partir de la propuesta de Potter y Wetherell de los repertorios interpretativos. Así comprobamos que se privilegia el uso de estrategias normalizadoras defensivas frente al riesgo de homofobia y ataque a la diversidad familiar. Se corre el riesgo de difuminar recursos y experiencias que pudieran contribuir a una construcción colectiva del fenómeno más rica, en su reflejo en avances sobre la acción legislativa, política y social.

Palabras clave: familias homoparentales; método cualitativo; normalización; repertorios interpretativos.

Introduction

The processes of change and democratization that modern societies have undergone since the late 19th century have affected social relationships in modern institutions at different speeds and intensities. The most important of these institutions include the family, school, work, and the media (Brullet, 2010). From the perspective of the social sciences, the set of changes that social relationships and family dynamics have undergone are among the most important manifestations of current social change. In fact, the family as an institution has always stayed within the variety of forms that meet the prevailing sociocultural, political, and economic conditions. To a greater extent than other social institutions, the family can only be understood by studying its movements and transformations (Parra, 2007). Thus, it is difficult to define the term "family" in such a way that includes all the aspects that characterize it and all the realities to which it has adapted over time. Authors such as Alberdi (1999) have proposed a definition of the nuclear family such that it must be formed by two or more people bonded by affection, marriage, or affiliation, and who have to live together, put their financial resources in common, and consume a range of goods together in their daily lives. Montano (2007) conceived of the family as an institution designed to meet basic material and emotional needs and to perpetuate the social order. In general, these definitions do not reflect the diversity of changes this institution is undergoing; however, they all include "affection and emotional support" as the constituent elements of any household. In order to give an accurate definition, it would be ideal to analyse the characteristics of a specific family structure within a particular historical, political, and social setting. Thus, the definition of family should include increasingly diverse circumstances (De Singly, 2000).

The traditional family model (formed by father, mother, and children) has remained constant for centuries, from preindustrial cultures to advanced industrialized ones (Del Campo, 2004), and it remains the prevailing family structure in most sociocultural settings. Nevertheless, it is clear that in the last three decades there has been a decrease in this type of structure, which now forms part of a variety of family structures that have arisen as an adaptation to new settings and ways of living together in society.

According to some authors (e.g., Gil, 2009), the so-called process of family mutation or metamorphosis began in Spain from the time of its transition to democracy. Demographic indicators have changed and therefore the concept of a family space that is subject only to the dictates of social obligations and economic needs is too narrow. The nuclear family, characterised by its rigid stable framework of relationships between the professional and domestic environments and sustained by patriarchal gender relationships, is giving way to a plurality of new forms of coexistence (Haveren, 1995). This situation has been considered to be a clear reflection of a "crisis" in the family world or even of its "death" (Fleischer, 2003). However, other readings suggest the need to rethink the future of an institution facing constant change (Castellar, 2010).

Pluralism is reflected in a remarkable diversity of ways of living as a family, significant changes at the different stages of life, and the increasing democratization of social attitudes towards the family and the type of relationships between family members (Rodriguez and Menéndez, 2003). In Spain, the following types of family are becoming less rare: nonmarital partnerships, couples without children, intercultural families, and families who have chosen to have children by alternatives such as adoption or assisted reproduction. This group also includes families formed by homosexual parents (i.e., the topic of this study), which is an indication of the incorporation of sexual diversity in the new debate on the concept of the contemporary family. New legislative developments related to the social recognition of sexual diversity mean that the parental experience has an increasing role in the gay community.

Different political, social, legislative, and technological factors converge in the growing empirical interest in the study of homoparentality as an alternative family reality. In recent decades, the fact of being homosexual is clearly no longer considered to be a mere anecdotal transgression, but has become a real engine of social change. Spain and other European, Anglo-Saxon, and Latin American countries have almost identical issues, although these issues are unfolding at a different pace and are driven by the confluence of historical and cultural traditions. Nevertheless, these countries are undergoing an accelerated process of social and legal changes in this area, including the consolidation of the gay and lesbian community as a social agent and the legalization of same-sex marriage. In Spain, a wide range of legislative reforms has recently been developed that provide a legal basis for adapting the law to a more democratic and egalitarian concept of the family and sexual relationships (Pichardo, 2009). The most important of these reforms is Law 13/2005, which allows same-sex marriage and other rights, such as the right to adopt. These legislative changes in the field of sexual diversity have been achieved largely due to constant pressure from LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) social movements, which are committed to supporting normalisation and equal rights for the collective and have significantly influenced the public and political spheres. Mention should be made of the representatives of queer theory, who have played a minority role in this process. Their arguments barely reached the media due to their use of a critical discourse that challenged the egalitarian solutions as being ones of submission and accommodation to the heteronormative hegemony.

Real interest in the study of homoparentality began in the 1970s in North America. In most cases, and in subsequent years, a quantitative methodology has been used with the sole purpose of comparing homoparental and heteroparental families in terms of their quality as fathers or mothers and the psychosocial adjustment of children raised in these families. In general, quantitative research, such as the longitudinal study by Golombok and Tasker (1996) and the pioneering study by González, Chacon, Gomez, Sanchez, and Morcillo (2003) in Spain, has found no significant differences in parenting between homosexual and heterosexual parents. It has also found that the psychosocial development of children raised in homoparental families is fully equivalent to that of children raised in heteroparental families. These results have led to a normalisation process. In turn, normalisation has contributed to the establishment of gay and lesbian-parented families, which are no longer understood as a social danger and now occupy a prominent place in the renewal of family models based on plurality and respect for difference (Pollack, 1995). Despite the positive results of these comparisons, in public and political platforms it is still maintained that homoparenting is not natural and may have an effect on the children's development. In fact, some experts and conservative socio-political strata have criticized the conclusions of these studies due to their lack of scientific rigour. They have suggested that the studies are limited because of the use of heterogeneous and biased samples provided by associations defending this collective. In addition, they emphasize the instability of homosexual couples and the tendency of children to imitate the sexual behaviour of their fathers or mothers (Cameron and Cameron, 1996). These arguments are based on a conservative ideology and have had a significant effect on the definition of an effective prohomoparental discourse based on normalisation strategies. It remains difficult to provide an alternative framework to mere heterocentric assimilation.

As a result, some prominent authors have recently begun to conduct research that is less comparative and defensive (Clarke and Kitzinger, 2004, Ceballos, 2009; Pichardo, 2009). The first qualitative studies were conducted in the 2000s. These studies attempted to explain and offer solutions to the paradox of comparative studies raised by most quantitative studies. They analysed the beneficial effects that could derive from the distinctive features of homoparenting, such as the more egalitarian relationships that the parents appear to practice in this type of family structure (Patterson, 1992).

From a critical perspective mainly based on lesbian theory, some studies (Clarke and Kitzinger, 2004) have attempted to resume these discussions from a constructionist perspective and have generally addressed gay and lesbian parenting as presented on television. The results of these studies show that the participating homoparents and supporting experts mount defensive and apologetic arguments orientated to the normalisation of this new family reality, reinforcing in an antinomic manner the legitimacy of the anti-homoparental agenda. These studies suggest that comparative research on homoparenting and heteroparenting should be replaced by studies designed to answer questions like "Why and how are homoparents oppressed?" and "How can this situation be changed?" Some research shows that the prohomoparental scientific discourse is obsessed with normalisation approaches that are not only the result of conservative attacks but also of the covert heterocentrist attitude found in many homoparental families.

These considerations form the basis of our interest in developing a qualitative approach that addresses three key questions:

1. How does research on an emerging social phenomena, such as homoparentality, approach the different dimensions of social intervention?

2. How does the audiovisual media construct, raise awareness of, and disseminate the homoparental phenomenon?

3. What are the discursive bases of prohomoparental opinion, especially that of experts, and how do they address normalizing effects?

These questions form the basis of the present study, which integrates various lines of research. We review the results obtained from three studies that addressed these issues and carefully examine the implications of recent theoretical developments.

These studies used a qualitative method based on discourse analysis (DA) (Potter and Wetherell, 1987). The next section describes the basic aspects shared by the method used in the three studies.

Method

A qualitative phenomenological design was used because it is well-suited to understanding the specific meaning that any processes or phenomena acquire within their emergent social and cultural settings. This approach provides a deeper understanding of the homoparenting phenomenon within the public spheres analysed.

The three studies used a type of procedure that is heir to the concept of "theoretical or purposive sampling" developed in the context of Grounded Theory.

Materials

Intentional sampling was used in the three studies. The materials used in the analysis were transcribed texts derived from discussion groups, audiovisual productions, and the document obtained from the session of the Comisión de Justicia del Senado Español (Spanish Senate Judiciary Committee). In general, the material comprised various publications, documentary reviews, fragments of social interactions, audiovisual productions, and so on, and whose literal transcription generated the analysis text. In the discursive approach, a detailed analysis of very specific materials is recommended. For this reason, intentional sampling was used. We did not attempt to obtain a representative sample in the positivist sense; instead, we used a sample of informants and specific documents that have a particular place within social discourse. Based on this approach, particular attention was paid to semantic content rather than paralinguistic components. The analysis addressed the documents only as texts within a given social setting (Cubells, Calsamiglia, and Albertín, 2010).

Analysis

The materials were analysed from a socioconstructionist approach, with a special focus on identifying the themes that the participants, documentaries, and prohomoparental experts used to talk about the sociocultural meanings related to homoparenting. A qualitative psychosocial method was used that combined discursive psychology with critical discourse analysis (i.e., DA and interpretative repertoires (IR) (Potter and Wetherell, 1987)). The IRs include various related elements that the speaker uses to build versions of events, actions, cognitive processes, and other phenomena. The presence of a repertoire is often marked by certain tropes or figures of speech, which typically comprise a limited number of terms used in a particular stylistic and grammatical manner that is usually derived from certain key metaphors. Repertoires reflect the internal structure of the different narratives that come together to build certain representations of reality (Potter and Wetherell, 1987). Therefore, rather than analyse and compare the content or positions of different social groups or categories, our objective was to identify the repertoires that drive discursive production through alternative logics. The existence a given repertoire is recognized by the type of narratives that characterize it; thus, the transcribed texts contained fragments, paragraphs, quotations, or prevailing ideas that characterised one of the repertoires but not the others.

Process

The analytical procedure followed in the three studies comprised four main phases:

- Search, selection, and preparation of the material (literal transcription of documents).

- Familiarization with the material through successive readings, confrontation of messages, and following lines of argument. This part of the process was independently conducted by each researcher.

- Analysis, identification of the general discourse strategies, and the subsequent provisional identification of IRs based on the detection of regularities. Discursive strategies are common lines of argument that speakers use to describe, explain, and, therefore, construct their own reality of the phenomenon in question. The set of discursive strategies form the different repertoires. In general, repertoires are discursive frameworks supported by the discursive strategies on which participants base their rhetoric.

In this phase, the reliability of the studies was improved by controlling for data generation and the transcriptions of the documents and discussion groups, thereby maintaining homogeneity between researchers.

All analyses were conducted using Atlas.ti. software version 6.0. The process was divided into two distinct nonsequential phases: textual level and conceptual level. The software was used in the first phase (textual level) to identify text segments (citations) during code construction, and in the second phase (conceptual level), to establish the relationships between codes in order to identify the repertoires.

- Validation; researchers share similarities and differences. This process was supported by a review of the IRs by three external researchers (two Spaniards and one Argentinian) with expertise on this topic and type of analysis. Different techniques were used in the validation process, such as searching for coherence and new problems, and identifying issues in the analytical process that may be relevant to similar future research. In each of the studies, the researchers used a triangulation approach to ensure the credibility of the analysis and the results, thus obtaining a consensus report of the IRs.

Description of the studies

Homoparentality and academia

Approach

Regarding the first question, we thought it would be of interest to link the study of the social construction of homoparentality to our qualitative teaching research project on the emergence of new contemporary social phenomena conducted with students following a social work degree. Our aim was to involve these students in the study so that they could increase their social awareness and action towards this reality while learning the use of qualitative methodology to study this phenomenon. The students not only worked on issues related to homoparental family diversity, but were also provided with the skills needed to be able to make a deep analysis of this reality. Thus, a research project was designed with students to analyse how social discourse toward homoparentality was constructed. In more specific terms, we sought to identify the discursive strategies employed to legitimize and construct this discourse in the academic world.

Participants

The study participants comprised teachers, researchers, and students in the academic setting. The sample comprised 21 members of the academic environment. Intentional sampling was used to select the sample.

Homogeneity criteria were: being a member of academia, familiarity with the social environment, and the same educational level or occupation. Heterogeneity criteria were: sex, age, and being students, teachers, or researchers from different courses. Inclusion criteria were: being a member of academia and agreeing to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria were: not being a member of academia and refusal to take part in the study.

Data collection

Data were collected through discussion groups, which comprised seven participants grouped by age and educational level or occupation. A script was used to guide group activity. The script was developed ad hoc from a theoretical review that allowed us to establish the main themes to be discussed. The groups comprised the same social work students involved in the research project. Group meetings lasted between 60 and 80 minutes.

Overall results

Five interrelated repertoires were identified: "Love makes a family", "We have made progress in rights but have we actually made progress?", "The influence of these families on the sexual orientation of their children", "The social construction of sexual and gender identity", and "Education as a source of social change".

Conclusions

A strong commitment to normalisation was observed, as shown by the discourse being subordinated to a mainly heterocentrist reality when talking about homoparenting.

As a consequence of the dynamics of the debate and our objectives to raise and spread social awareness of this topic, we decided to identify the types of active materials that are being used to educate, inform, and increase visibility from a prohomoparental perspective. These considerations motivated the second study.

The construction of homoparentality found in audiovisual productions

Approach

The media has been influenced by intense activism associated with raising awareness and increasing visibility, which developed following the same-sex marriage law. It offers a wide range of audiovisual means of expression that makes the homoparental experience accessible to the public through the news, newspaper articles, documentaries, "talk shows", forums, and websites. We analysed the production of different audiovisual documents that seek to increase the social visibility of homoparental families. This medium or route is used as an educational tool to help the public understand the plurality of family relationships. We analysed how the homoparental experience is constructed in relevant media channels such as audiovisual production.

Materials

The materials comprised a range of prohomoparental audiovisual productions. Intentional sampling was used to search for documentaries supportive of gay and lesbian parenting. Six documentaries were chosen from a total of the 63 that were reviewed. The selected documentaries were: "Mis padres son gays", "Queer spawn", "Homo baby boom", "Dos padres, dos madres", "Right 2 love", and "Familias por Igual". These materials were located by searching various channels: for example, film festivals specialized in these types of documentaries, materials available in associations and institutions, national and regional television media archives, and university audiovisual archives. Inclusion criteria were: Being widely available during the long period covering the debate, the approval process, and the first years of the same-sex marriage law. The materials covered a wide range of topics, explored questions about identity, parental roles, prejudices, the future sexual orientation of their children, and the evolution of these families within the legal and social framework (authors). Regarding homogeneity criteria, all the documentaries had to deal with legal and social aspects, and those related to family dynamics. Heterogeneity criteria were diverse according to the organisation or association that produced the documentaries and the countries involved (mainly European and Latin American).

Overall results

Four IRs were identified: "Building Identity", "Visibility and Familiarity", "Homoparental Family: A Possible Option", and "Sexual Orientation".

Conclusions

It was found that these documentaries make efforts to defend equality against the risk of homophobia and attacks on family diversity. A social reality is revealed of prohomoparental approaches that are legitimized by a political and social discourse based on normalisation strategies. Thus, the homoparental phenomenon is assimilated within the experience of parenthood in heterosexual relationships and the presence of differential elements that may be uncomfortable are minimised (authors).

From its beginnings, the "Lesbo-Gay Baby Boom" has attracted the attention of the media and expert discourse during its process of becoming visible and its construction as an emerging social phenomenon. For this reason, and based on the foregoing considerations, we conducted a third study to investigate the role of prohomoparent experts in advising politicians on the same-sex marriage law in Spain.

Homoparentality and expert discourse

Approach

In recent years, expert opinion has acquired a privileged position in assessing and legitimising the implementation of legal and legislative decisions and policies that ratify new non-conventional family forms. This role has received much interest from researchers working in the social sciences.

Following the legalization of gay marriage and the adoption of children by homosexual couples, there has been increased debate in the media on families formed by gay and lesbian parents. These new forms have numerous defenders and detractors, who take the most progressive and the most conservative positions, respectively. Opinions mainly address the issue of whether growing up in a homoparental family is harmful to the child's development as a person in a range of significant social settings.

Based on the above, the third study analysed the role of expert, scientific, and professional discourse (especially legal and psychological discourse), in the political debate on gay and lesbian parenting in Spain. However, we did not attempt to identify the different lines of arguments used by pro- and anti-homoparenting experts. Instead, we identified the normalisation strategies used in prohomoparental discourse and their effect on the construction of political debate and the social construction of homoparenting.

Materials

The text material comprised the report of the Comisión de Justicia del Senado Español (Spanish Senate Judiciary Committee) held on 20 June 2005. The agenda dealt with expert presentations concerning the Bill on amending the Civil Code on the right to marry and, in particular, the effects on the development of children living with homosexual couples. The agenda comprised 74 pages in which the experts were identified by name, professional affiliation, and the parliamentary group which proposed them. This document was of interest because there was an obvious difference, in some case self-reported, between the experts involved. Thus, it was possible to identify anti- and prohomoparental experts. In the third study, we identified and discussed the normalisation strategies used by prohomoparental discourse.

In line with other studies (e.g. Clarke, 2002), we took a constructionist approach to understanding the use of scientific discourse by prohomoparental experts, and the rhetorical construction of the phenomenon they offer to the public authorities seeking advice (Iniguez and Pallí, 2002).

Overall results

Based on the material analysed, three fundamental IRs were identified: "Depathologise", "The Question of Rights", and "Gender vs Sex".

Conclusions

We found that prohomoparental positions are empirically supported and have the professional endorsement of the international community. Despite some limited scientific support, antihomoparental pressure is essentially based on the defence of the natural order of sexuality and the family. This perspective still has undue influence on shaping the agenda of homoparenting, which makes prohomoparental experts devote many dialectic resources to counterarguments that, in many cases, we can consider to be homophobic. The third study found that within the group of prohomoparental experts there was a predominance of normalizing strategies. However, there was also a minority of strategies committed to respect for differences, sexual identity, and social flexibility in the perception of gender roles, but which typically remained in the background (authors).

Discussion

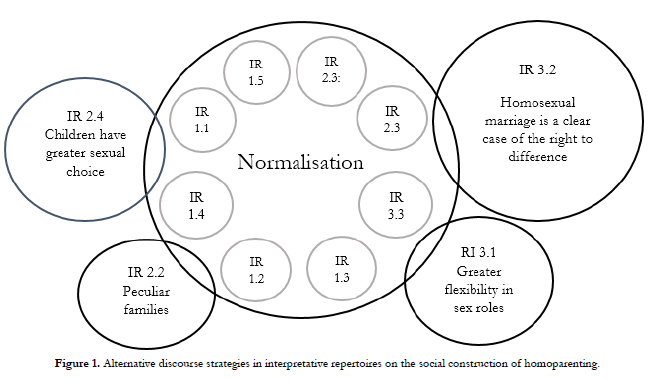

The findings of the three studies are directly or indirectly in agreement. In general, discursive strategies of assimilation are used to normalize homoparenting. Table 1 shows the different repertoires grouped by the discursive strategies they share.

IR 1.1 and IR 1.5 appear as cross-sectional arguments in most interventions conducted in research studies and therefore have become the fundamental support of discourse. This aspect emphasizes the importance of these families in providing love, care, affection, and education.

Extract IR 1.1: "What is important is that the child grows up in a respectful environment, that there is affection, love, and good education."

These discursive strategies are presented as positive elements in homoparental families to offset the negative consequences of homosexuality. Thus, homoparentality is a new way of structuring the family system that replaces the rules of procreation, affiliation, and alliance with love, care, affection, and education. These strategies may suggest that gay fathers and lesbian mothers are only good in "emergency" situations (i.e., when better "options" are unavailable), given that placing children in institutions can involve greater risks than fostering or adoption.

Extract IR 1.5: "Providing they love them and treat them right, that seems fine to me, because look at how many kids there are in orphanages, or are poor and living alone on the streets and begging".

IR 3.1 suggests that no evidence has been accepted with a high degree of consensus by the scientific community that shows significant differences in a set of indicators of adjustment between children raised by homosexual or heterosexual parents. Similarly, IR 2.3, which is closely linked to IR 3.1, shows, in general terms, how gay couples and their children shape their intimate spaces in terms of everyday life and family dynamics, and in doing so, resort to the discursive strategies of love, care, and affection described in IR 1.1 and IR 1.5.

IR 1.2, IR 2.2, and IR 3.2 are mainly characterized by the predominance of discursive references to several main issues, which include: access to marriage, defending the rights of their families (especially regarding children), and the poor relationship between social progress and legal rights. The tension between the concept of marriage as a right and children's rights, which is generally resolved by appealing to their protection, and the emotional quality-suitability pair, leaves little room for the generation of alternative arguments to those based on normalisation.

Extract IR 2.2: "We went from illegality to recognition and legality, especially for children ..."

IR 1.3 and IR 2.4 show the uncertainty caused by the "conditioners" of sexual orientation and the influence that homoparents could have on the sexual choice of their children.

Extract IR 2.4: "She wanted to be certain, to be sure that she's been a good mother and part of that for her was having raised a "normal child "..."

IR 1.4, IR 2.1, and IR 3.3 indicate the difficult relationship between sexuality and homosexual parenting. In fact in many cases, both dimensions are presented dichotomously, giving priority to gender identity when discussing homosexuality and to sexual practice when referring to the area of intimate relationships.

Extract IR 3.3: "Neither homosexuality nor homosexual relationships are a social or psychological problem and cannot be of clinical interest as such, as I said before. For the professional, this is not even a matter of inquiry because it is part of the private domain and any person is free to chose to speak about it or not."

However, linked to some of the repertoires, some elements emerge that hinder the normalisation argument through alternative discursive practices that can provide new keys to the social construction of homoparentality. These elements can be considered as potential transformers of different interventions and professional practices that sustain the discourse established in each of the studies. Figure 1 shows repertoires that choose normalisation discourse strategies but use some language strategies that indicate differences.

IR 2.2 and IR 3.2 indicate the tension between the concept of marriage as a right, the rights of children, and the insufficient acquisition of social rights. Some alternative items can be seen in these repertoires, as discussed in the next excerpt, in which the need for laws to be changed is acknowledged in order to offer practical solutions to a homoparental reality that already exists and could even be stimulated by the implementation of specific legal measures.

Extract IR 3.2: "We carried out this reform, as I say, with not a few problems within the government and within the parties forming the coalition government, but convinced that a reform like this should be made because there was a need -- which I mentioned at the beginning of my speech -- because society was calling for it. It was not a question of anticipating a need, it was a question of giving a solution to a reality that in some cases openly existed and that in other cases was becoming a reality due to the numbers involved..."

The right to be different is also mentioned by a minority with clearly transformative nuances. However, this right is discussed only in the context of marriage, rather than directly addressing homosexual parenting.

Extract IR 3.2: "This is what constitutional equality means, and gay marriage is a clear case of exercising the right to be different, which has been discriminated against, and the right to be different has been hindered as consequence of a sexual orientation..."

Some interventions, although few, advocated for the uniqueness of these families.

Extract IR 2.2: "...but ours are peculiar families. Homosexual parents do not want to recognise this peculiarity, almost certainly because their capacity to raise children might be questioned."

IR 2.4 shows that several participants (children of gay or lesbian parents) believe that knowing about the marital life of parents helps children to freely choose their sexual orientation. Thus, greater social flexibility is illustrated in the perception of gender roles in the homoparental setting.

Extract IR 2.4: "I think that the parents' sexuality influences their children's sexuality. I think that it has an influence in the sense that it increases or expands their range of possibilities."

In IR 3.1, some experts emphasize the fact that certain publications have even reported favourable differential effects in homoparental homes where greater flexibility has been shown in the perception of gender roles and acceptance of homosexuality. Nevertheless, these data are often viewed more as favourable indicators of "the homoparental experiment" rather than as a possible route for the construction of the phenomenon regardless of the repeated heterocentric comparisons. Some lines of argument that could have been more deeply examined in the proceedings analysed are shown in the following extract.

Extract IR 3.1: "It is accepted that it's much better to have different types of families; there is greater acceptance of the differential fact of sexual orientation such as homosexuality, but the next point is very important, ladies and gentlemen, because of the media impact this has - greater flexibility in the exercise of sex roles. Thus, machismo is potentially in crisis, and that's fine."

However, in some minority interventions, critical questions arise about whether there is a real need to empirically justify the effects of homoparentality on children. This opens the possibility of an alternative reading of the accumulation of scientific evidence. The demand that homosexual parents as a collective should undergo suitability tests that under no circumstances are asked of people in other social categories is rejected. If, as a first step, it is accepted that homosexuality has long ceased to be considered a psychological problem, then homoparentality becomes irrelevant as a subject of clinical interest or professional inquiry. The suitability of homosexual parents should not be assessed on a priori conditions, such as sexual choice and the consequent life style, but rather by determining the causes underlying the risk of a general lack of protection.

Extract 3: ABP: "...I'd like to say that this is the first time I know of that previous studies have been requested to assess the suitability of people to adopt. There are voices saying that before homosexual couples can jointly adopt, preliminary studies that confirm their suitability are needed. In no other case has the issue [of adoption] been considered in this way..."

Conclusions

The three studies addressed the issue of the construction of homoparentality in the public sphere (academia, media documentaries, and the expert professional-legal setting). That is, the studies investigated three different public spheres, each having different responsibilities, modalities, scope and, to some extent, audiences. However, the three spheres cannot be thought of as closed areas or absolutely independent of each other. They overlap, and the discourse produced in each one intersects with the others such that they feed and challenge each other. In fact, we can think of academia as the setting in which specialized knowledge is created that strengthens the expert domain. This is done through the training of students, who will be future professionals with specialized knowledge, and through the actual teaching and research conducted in the academic setting. The experts provide academia with feedback based on their applied knowledge that enters into dialogue with the university and empirical discourse in different settings (e.g., collaboration between institutions and businesses, congresses, etc). The media disseminates specialized knowledge to the general public. It also "amplifies" knowledge rooted on fixed social practices and beliefs by putting forward "common sense" arguments that question the other two spheres (involved in the construction of new collective mentalities). More specifically, we analysed the discursive strategies employed to present the experience of homosexual parenthood and the consequences in the definition and social construction of the phenomenon itself.

Initially, we attempted to integrate and enable a new line of knowledge production within the discipline of social work with the aim of making students aware of these new social realities and training them in qualitative methodology. For these reasons, we designed the research project together with social work students. The project was intended to be a first encounter of the students with the homoparental family scenario. The objective was that students could enquire into and gain insight on the issues on which the sociocultural meanings related to homoparentality are being constructed.

We concluded that when people speak of homoparenting they do so from a position that is subject to comparisons between homoparents and heteroparents, and so innovative differences within homoparental families remain hidden. In this way, the predominant and obligatory heterocentric norms are still considered to be the pillars on which our society is founded. It was observed that the traditional family model is present in the construction of the social practices that make up the homoparental phenomenon. It was also shown that, in general, people who discuss this type of subject try to do so from a tolerant position that sometimes promotes the preservation of heterosexist behaviour (e.g. Clarke and Kitzinger, 2004). We found that, under apparently progressive language, the terms related to differences in these families mask situations of inequality and discriminatory actions. Homoparentality is still subject to deep ignorance, which maintains the preconceptions and unfounded judgments surrounding the topic. This situation can permeate professional activity. We therefore consider it essential that psychosocial intervention professionals have a knowledge base and a set of tools that help them understand the aspects linked to social change that emerge from the experience of the new family forms. The long-established focus on heteroparental families and social interventions directed at this family structure should not lead to heterocentrism in the social work profession, but rather the opposite. These types of projects are intended to provide students with alternative strategies that to a great extent should facilitate the development of intervention programs aimed at the gay community, where the decentralisation of heterocentrism is the main objective. That is, they are provided with socially productive awareness and visibility programs such that they can treat the gay community as being equal but different and are not only limited to maintaining established values.

Based on the conclusions of the first study, and the desire to continue working on raising awareness and increasing the visibility of the group in academia, the second study addressed prohomoparental documentaries.

Most documentaries emphasize inclusion and equality in terms of homogenization and assimilation to a standard of deeply rooted social practices. Thus, they do not show any particular interest in including innovative aspects by showing the tension between equality and respect for difference. They prefer to assimilate the fact of homoparenthood to heterosexual relationships and to minimize the differential elements that may be uncomfortable. The potential defence of the differences of homoparental families, based on the necessary opposition of this choice to macho and (neo) liberal values, often tends to be misunderstood by the public and has the unintended effect of social rejection. This commitment to normalisation, which most homosexual parents prefer, paradoxically references discourse that idealizes the image of the traditional family and enables homoparents to cope with heteronormative comparisons. References to equality to some extent reassure society and allow them to recognize and accept these families, while placing them in a subordinate position ("the family next door"). In general, the dominant narratives on homosexual parenting can reinforce the oppression and control these couples experience, and in many cases raises the need to challenge the normalizing experiences of homoparental families. The fact that these families do not openly talk about their differences can prevent them from expressing their true experiences, and may particularly affect the channels through which they can speak for and of themselves. Normalisation is the predominant strategy used by prohomoparental documentaries to offer to homoparents a non-discriminatory position in reference to their inclusion in the family institution. Politically, this approach is framed within the assimilation tactics that a large part of the LGBT movement has used since its inception. Increasing the visibility of minority groups, including the gay and lesbian collectives, has been a key aspect of overcoming social exclusion, which has led to the progressive development of social normalisation and the lifestyle of homosexual people (Fernandez, 2007).

These aspects illustrate the paradox facing us: On the one hand, they help raise awareness and make visible the reality of these families; on the other they contribute to the fact that homosexuality as a sexual orientation and homopa-rentality as a family group is a possible choice only to the extent that heteronormative patterns, like the heterosexual nuclear family, are respected, recognized, and reproduced. In general, documentaries fit a behaviour pattern that to a great extent generally ensures social acceptance and avoids discrimination, but through the use of defensive strategies may lead to self-censorship among these families, as mentioned above.

In the first and second study, the discourse was mainly constructed on the basis of normalisation. In line with the approach of Clarke (2002), we wanted to investigate this aspect in terms of the costs and political benefits generated by normalisation in order to know the price of normalisation strategies when presenting homoparentality as a family model compatible with the dominant heterocentrism and to see what elements of homosexual parenting often remain invisible and excluded.

Thus, the third study avoided comparisons between the arguments of anti- and prohomoparental expert discourse. The construction of homoparental reality is mainly generated through the active role of these experts in the conceptual establishment of problem-solution dyads, their prioritization, and the reinforcement of specific agendas in political and social debate (Clarke, 2002). In general, the foundation of this activity is rhetoric and it relies on discursive practices that transform debates, such as those on the Spanish family today, into an element of social control. We addressed the normalisation strategies followed from favourable stances toward homoparenthood. We are aware that prohomoparental positions have empirical and professional support in the international community. Despite some limited scientific support, antihomoparental pressure is essentially based on the defence of the natural order of sexuality and the family. This perspective still has undue influence on shaping the agenda of homoparenting, which makes prohomoparental experts devote many dialectic resources to counterarguments that, in many cases, we can consider to be homophobic. Obviously, the direct expression of antihomoparental discourse is usually openly and unanimously rejected by many public and professionals institutions that accept the overwhelming international empirical evidence that there are no differences in parenting between hetero- and homosexual families. Nevertheless, antihomoparental speech clearly structures the political agenda and media debate by repeatedly introducing various questions, based on a methodological-moral dyad, that prohomoparental positions can only address defensively and by the use of normalizing arguments (authors).

This type of implicit normalisation of homosexuality and homoparenting reflects the complex articulation between bio-power, rooted in the different antinomies of scientific tradition, and the contemporary construction of sexuality and the family based on a strikingly heterosexualised matrix (Butler, 1990; Foucault, 1996). Within the militant international gay and lesbian collective, the debate on assimilation-ism reveals the dilemma facing progressive discourse in the attempts to construct practices of resistance and change in the domination structures (Arditi and Hequembourg, 1999).

As in previous studies, we chose to assimilate homo- and heteroparenthood, putting aside the differential elements due to being a homoparent, which could even be confused with uncomfortable implicit negative assumptions or even with social danger. Thus, during the process, resources, experiences, and nuances become overlooked that could contribute to a more fertile expert construction of the phenomenon at the legislative, political, and social level.

We consider that the search for social acceptance via strict normalisation strategies that turn homoparenthood into something familiar and reliable has fulfilled its mission. After more than a decade, expert discourse should have overcome its defensive posture. It should be able to generate and adopt a new collective meaning for homoparenthood and develop alternative elements that use resistance and the generation of conflict for change to challenge the locked-in assimilationist perspective (Clarke and Kitzinger, 2004). For example, from merely anecdotal accounts, we should extract evidence that illustrates greater social flexibility in the perception of gender roles in the homoparental environment. This would allow us to venture less conventional formulas of normalisation in the definition of sexual orientation and the recognition and management of differences.

The idea of normalisation has caused considerable controversy within queer theory, which calls into question the "desire" to assimilate, because it is thought that egalitarian and accommodative solutions reflect an expression of submission to the heteronormative hegemony (Butler, 2004; Crawley and Broad, 2008). From this perspective, gay and lesbian identity is prioritized on the basis of the difference, desire, and the non-restrictive practice of sexuality. This contrasts with normalizing strategies, that is, with the wish expressed by some homoparents that they are recognized as a couple and family in the same terms in which heterosexual society is constituted. Faced with this conceptual dichotomy, authors such as Arditi and Hequembourg (1999) argued that any type of social change can only be achieved by combining normalisation and alternative strategies that are applied simultaneously in a particular field of power. Similarly, we consider it to be necessary to combine both principles in the same struggle and the same achievement. This would only be possible if homoparental families, in the setting of social institutions, were able to include and show the types of relationships that often remain hidden or excluded. In this line, Gimeno (2009) suggested that it would be of interest to take into account the struggle to improve the quality of life of homosexual people (derived from access to legal equality), and the fact that marriage could be a silent "bomb" in the heart of heterosexism. If we accept that marriage is a major tool of heterosexism, homosexual marriage may have a transformative capacity and a subversive impact on the social order that some seek to reinforce. We may also raise the issue of whether homosexual marriage in itself can be viewed as a paradox. We understand this in the sense that this normalizing process may cause substantial changes in the lives of the individuals involved that are emancipating (i.e., it liberates them from oppression and denaturalizes the concept of the "normal" family; Biglieri, 2013).

In conclusion, although we recognize the practical benefits and costs of using arguments related to equality and normalisation, we raise the following question regarding the present social order: Is it possible to go beyond the logic of the equality-normalisation dyad? We believe that research is needed that transcends this dyad and that arguments related to equality are exclusively used in the fight for justice. A fUrther question is: What would be the consequences?

It was definitely not our aim to determine whether homoparents are the same or different from heteroparents, especially bearing in mind that any response to this issue could be attributed to a subordinate position. From our constructionist perspective, what really concerns us is the way in which these families are being constructed as equal and as different (equality via the difference), and the various interests operating in this construction. Thus, as a result of our third study, and taking into account that both normalizing and alternative strategies are unlikely to become definitive and useful in every social, political, and historical setting, we ponder whether there are other ways to claim, defend, and construct marriage and homoparenthood that is not exclusively based on the heterocentrist perspective. In this sense, it would be interesting to analyse how homoparenthood is constructed in other countries, especially in Latin America due to the recent passage of laws that allow same-sex marriage, to see if normalizing strategies tend to transform social categories or, depending on the social, historical, and political setting, if the new categories risk being "domesticated" by the rules of normative heterosexuality.

Referencias

1. Alberdi, I. (1999). La nueva familia española. Madrid: Taurus. [ Links ]

2. Arditi, J. y Hequembourg, A. (1999). Modificaciones parciales: discursos de resistencia de gays y lesbianas en Estados Unidos. Política y Sociedad, 30, 61-72. [ Links ]

3. Biglieri, P. (2013). Emancipaciones acerca de la aprobación de la ley del matrimonio igualitario en Argentina. ICONOS, 46, 145-160. [ Links ]

4. Butler, J. (1990). Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Londres: Routledge. [ Links ]

5. Butler, J. (2004). Deshacer el género. Barcelona: Paidós. [ Links ]

6. Brullet, C. (2010). Cambios familiares y nuevas políticas sociales en España y Cataluña. El cuidado de la vida cotidiana a lo largo del ciclo vital. Educar, 45, 51-79. [ Links ]

7. Cameron, P. & Cameron, K. (1996). Homosexual parents. Adolescence, 31, 757-776. [ Links ]

8. Castellar, A. F. (2010). Familia y homoparentalidad: una revisión del tema. Revista Ciencias Sociales, 5, 45-70. [ Links ]

9. Clarke, V. (2002). Sameness and difference in research on lesbian parenting. Journal of Community and Applied Psychology, 12, 210-222. [ Links ]

10. Clarke, V. & Kitzinger, C. (2004). Lesbian and gay parents on talk shows: Resistance or collusion in heterosexism. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 1, 195-217. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/1478088704qp014oa. [ Links ]

11. Crawley, S. & Broad, K. L. (2008). The construction of sex and sexualities. En J. Holstein & J. Gubrium (Eds.), Handbook of constructionist research (545-566). New York: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

12. Ceballos, M. (2009). La educación formal de los hijos e hijas de familias homoparentales: familia y escuela a contracorriente. Aula Abierta, 37, 67-78. [ Links ]

13. Cubells, J., Calsamiglia, A. y Alberetín, P. (2010). El ejercicio profesional en el abordaje de la violencia de género en el ámbito jurídico-penal: un análisis psicosocial. Revista Anales de Psicología, 26(2), 369-377. [ Links ]

14. De Singly, F. (2000). L'individualisme dans la vie commune. Paris: Nathan. [ Links ]

15. Del Valle, T., Apaolaza, J. M., Arbe, F., Cucó, J., Díez, C., Esteban, M. L., Etxeberria, F. & Maquieria, V. (2002). Modelos emergentes en los sistemas y relaciones de género. Madrid: Narcea. [ Links ]

16. Diario de Sesiones del Senado (2005), Comisión de Justicia, celebrada el lunes, 20 de junio de 2005. VIII Legislatura. Comisiones, 189. Madrid: Cortes Generales. [ Links ]

17. Fernández, V. (2007). Visibilidad y escena gay masculina en la ciudad española. Documentos de análisis geográfico, 49, 139-160. [ Links ]

18. Fleischer, D. (2003). Clínica de las transformaciones familiares. Buenos Aires. Gramma. [ Links ]

19. Foucault, M. (1996). Foucault Live: Interviews, 1961-1984. New York: Semio-text (e). [ Links ]

20. Gil, E. (2009). Metamorfosis del conflicto familiar: género y generaciones. Panorama Social, 10, 40-51. [ Links ]

21. Gimeno, B. (2009). La institución matrimonial después del matrimonio homosexual. ÍCONOS, 35, 19-30. Recuperado de http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/509/50911906002.pdf. [ Links ]

22. Golombok, S. & Tasker, F. (1996). Do parents influence the sexual orientation of their children? Findings from a longitudinal study of lesbian families. Developmental Psychology, 32 (I), 3-11. [ Links ]

23. González, M. M., Chacón, F., Gómez, A., Sánchez, M. A. y Morcillo, E. (2003). Dinámicas familiares, organización de la vida cotidiana y desarrollo infantil y adolescente en familias homoparentales. Estudios e investigaciones 2002. Madrid: Oficina del Defensor del Menor de la Comunidad de Madrid. [ Links ]

24. Haveren, T. K. (1995). Historia de la familia y la complejidad del cambio social. Boletín de la Asociación de Demografía Histórica, XIII, 99-149. [ Links ]

25. Íñiguez, L. y Pallí, C. (2002). La Psicología Social de la ciencia: Revisión y discusión de una nueva área de investigación. Anales de Psicología, 18(1), 13-43. [ Links ]

26. Montaño, S. (2007) El sueño de las mujeres: democracia en la familia. En I. Arriagada (Coord). Familias y políticas públicas en América Latina: una historia de desencuentros (77-90). Santiago de Chile: Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL). [ Links ]

27. Parra, A. (2007). Relaciones familiares y bienestar adolescente. Madrid: Grupo editorial Cinca. [ Links ]

28. Patterson, C. J. (1992). Children of lesbian and gay parents. Child Development, 63, 1025-1042. [ Links ]

29. Pichardo, J. I. (2009). Homosexualidad y familia: cambios y continuidades al inicio del tercer milenio. Política y Sociedad, 46, 143-160. [ Links ]

30. Pollack, J. S. (1995). Lesbian and gay families: Redefining parenting in América. New York, NY: Franklin Watts. [ Links ]

31. Potter, J. & Wetherell, M. (1987). Discourse and socialpsychology: beyond attitudes and behavior. London: Sage. [ Links ]

32. Rodríguez, I. y Menéndez, S. (2003). El reto de las nuevas realidades familiares. Portularia, 3, 9-32. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Laura Domínguez de la Rosa.

Facultad de Estudios Sociales y del Trabajo.

Departamento de Psicología Social, Trabajo Social,

Antropología Social y Estudios de Asia Oriental.

Universidad de Málaga (España).

Avda. Francisco Trujillo Villanueva, s/n, 29001,

Málaga (España).

E-mail: ldominguez@uma.es

Article received: 27-04-2015

revised: 20-11-2015

accepted: 05-12-2015