Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Anales de Psicología

versión On-line ISSN 1695-2294versión impresa ISSN 0212-9728

Anal. Psicol. vol.33 no.2 Murcia may. 2017

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.33.2.240061

Influence of psychopathology on the perpetration of child-to-parent violence: differences as a function of sex

Influencia de la psicopatología en la comisión de violencia filio-parental: diferencias en función del sexo

Jaime Rosado, Eva Rico and David Cantón-Cortés

University of Málaga (Spain)

This study received a grant for open access publication by the University of Malaga (Spain).

ABSTRACT

The aim of the present study was to analyze the role of the psychopathologic symptomatology of participants on the perpetration of child-to-parent violence (CPV), as well as to test the moderator role of the participant sex on the psychopathology.

The sample comprised 855 students from middle school, high school and vocational education (399 boys and 456 girls). Age range varies among 1321 years old (M = 16.09; DT = 1.34), being 307 (35.9%) among 13-15, 501 (58.6%) 16-18 and 47 (5.5%) 19-21. Most of them (91%) had Spanish citizenship. Psychopathology was assessed with the Symptom Checklist 90 Revised, whereas CPV perpetration was assessed employing the Child-to-Parent Aggression Questionnaire.

Hierarchical multiple regression analyses showed that the most important psychopathologic symptoms were hostility, paranoid ideation and depression, being related higher scores on hostility and paranoid ideation, and lower on depression, with the perpetration of CPV. Interaction analyses showed a moderator role of the participant sex with the interpersonal sensitivity and obsessive-compulsive in the case of CPV to the father, and interpersonal sensitivity, obsessive-compulsive and paranoid ideation in the case of CPV to the mother.

Results confirm the idea that the existence of psychopathologic symptomatology by the minors has an effect on the probability of perpetration CPV, being this effect different depending on the sex of the perpetrator.

Key words: Child-to-parent violence; psychopathology; sex; dysfunctional psychological symptomatology.

RESUMEN

El objetivo del presente estudio fue analizar el papel de la sintomatología psicopatológica de los participantes sobre la comisión de violencia filio-parental, así como comprobar el rol moderador del sexo del participante sobre dicha sintomatología.

La muestra estuvo compuesta por 855 estudiantes de 3o y 4o de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria, 1o y 2o de Bachillerato y Formación Profesional (399 chicos y 456 chicas). Sus edades estaban comprendidas entre los 13 y 21 años (M = 16.09; DT = 1.34), teniendo 307 (35.9%) de ellos entre 13 y 15 años, 501 (58.6%) entre 16 y 18, y 47 (5.5%) entre 19 y 21. La gran mayoría (91%) tenían nacionalidad española. La existencia de psicopatología se evaluó mediante la escala Symptom-Checklist-90-Revised, mientras que la comisión de la VFP se evaluó mediante el Child-to-Parent Aggression Questionnaire.

Los análisis de regresión lineal múltiple jerárquica indicaron que los principales síntomas psicopatológicos en la comisión de VFP son la hostilidad, ideación paranoide y depresión, estando relacionadas puntuaciones superiores en hostilidad e ideación paranoide, e inferiores en depresión con la comisión de VFP. El análisis de interacciones mostró un papel moderador del sexo del participante con la sensitividad interpersonal y las obsesiones, en el caso de la VFP hacia el padre, y sensitividad interpersonal, obsesiones e ideación paranoide en el caso de la VFP hacia la madre.

Los resultados confirman la idea de que la existencia de una sintomatología psicopatológica por parte de los menores tiene un efecto sobre la probabilidad de comisión de la VFP, siendo este efecto diferente en función del sexo de la persona agresora.

Palabras clave: Violencia filio-parental; psicopatología; sexo; sintomatología psicológica disfuncional.

Introduction

The abuse of a child towards his/her parents, also known as parental violence (CPV), constitutes a serious social and family problem due to its short- and long-term consequences, which not only directly affect the victim but also generate a rupture within the family nucleus (Gallagher, 2008). Moreover, in recent decades, and especially nowadays, its frequency and severity has increased (Coogan, 2012; Nowakowski-Sims & Rowe, 2015).

This type of violence is defined as that "in which the child acts intentionally and consciously with the desire to cause harm, prejudice and/or suffering towards his/her parents, repeatedly over time, and with the immediate aim of obtaining power, control and dominance over his/her parents in order to achieve something through psychological, economic and/or physical violence" (Aroca, 2010).

The data obtained on the prevalence of CPV has not yielded conclusive data, finding very different percentages across studies. In Aroca's (2010) literature review, the prevalence ranged between the 30.8% found by Langhinrichsen-Rohling and Neidig (1995) and the 3.4% found by Laurent and Derry (1999). With regard to the frequency and prevalence of CPV in Spain, there are numerous Spanish studies but the majority has used small clinical samples, with relatively few studies having representative samples of the community. The most recent studies with representative samples again provide very different data on the prevalence of CPV. These studies have found a prevalence rate that varies between 4.6% and 65% according to the type of violence committed (Calvete, Orue & Gámez-Guadix, 2013; Calvete, Orue & Sampedro, 2011).

Regarding the gender differences in aggressive behaviors towards parents, although CPV is exercised by both boys and girls (Gámez & Calvete, 2012; Tobeña, 2012), there are differences with respect to the type of violence each of them exert. It has been shown in several studies that boys exercise physical violence more often and girls exert more psychological violence (Cuervo & Rechea, 2010; Ibabe & Jaureguizar, 2011).

Previous studies have found that certain family variables are risk factors for the development of CPV (Gámez-Guadix & Calvete, 2012; Ibabe, 2015). Traditionally, CPV has been associated with a number of family risk factors related to other forms of violence within the family, such as exposing the child to situations of gender violence (Gámez-Guadix & Calvete, 2012; Lyons, Bell, Fréchette & Romano, 2015), or even child abuse (Routt & Anderson, 2011). But the main family factor according to many studies is the parenting style exercised by parents (Calvete, Gámez-Guadix & Orue, 2014; García-Linares, García-Moral & Casanova-Arias, 2014; Ibabe, 2015).

On the other hand, scientific literature has revealed a series of psychological factors that facilitate the understanding of this type of violence. Regarding the psychological variables, several studies have found a strong correlation between children's aggressions towards their parents and feelings of loneliness, low life satisfaction, lack of empathic ability or low self-esteem (Aroca-Montolío, Lorenzo-Moledo & Miró-Pérez, 2014; Cotrell, 2001; Estévez, Murgui & Musitu, 2009). Other studies have found that both a high level of impulsivity (Contreras & Cano, 2015) and alcohol or drug consumption predict CPV, although with respect to the latter variable the results are contradictory (Routt & Anderson, 2011).

However, most research has focused mainly on family factors, and thus, the present study focuses especially on the analysis of psychological factors predictors of CPV. In the past, isolated studies have analyzed the role of certain psychopathology traits independently (Calvete et al., 2011; De la Torre, García, De la Villa & Casanova, 2008; Routt & Anderson, 2011). Calvete et al., for example, found a relationship between depression and the probability of committing verbal and physical violence towards parents in a sample of 1427 adolescents. Nevertheless, to date, no study has jointly analyzed a wide range of psychopathological symptoms. The present study has as its main objective to establish the existing relationships between children's psychopathological symptomatology and the different types of aggression of children towards their parents (physical, psychological, economical and total), controlling the possible effects of the minor's sex, the importance allocated to studies, the consumption of drugs and alcohol on behalf of the minor and his/her perception on the consumption of his/her parents.

Likewise, due to the possibility of psychopathological symptomatology affecting children differently according to their sex, the existence of possible interactions between psychopathology and the children's sex was analyzed. In this way, it was verified whether the relationship between the psychopathological symptomatology and CPV towards the father and the mother varied according to the sex of the minor.

Method

Participants

The sample of the present study consisted of 855 participants (399 boys and 456 girls), from 11 secondary education institutes randomly selected in the provinces of Málaga and Granada. Their ages ranged between 13 and 21 years (M = 16.09; SD = 1.34), with 307 of them (35.9%) aged between 13 and 15 years old, 501 (58.6%) aged between 16 and 18, and 47 (5.5%) aged between 19 and 21. All students were enrolled in 3rd and 4th year of compulsory secondary education, in the last two years of high school and in Vocational Training.

The majority of the participants (91%) were Spanish, with the remainder being from United Kingdom (1%), Argentina (0.6%), Morocco (0.5%), Italy (0.5%) and Dominican Republic (0.4%). Regarding the parents of the adolescents, the majority (87.2% of fathers and 87.5% of mothers), were of Spanish nationality. The parents of 73.7% of the adolescents were married, 20% were separated, 3.8% were cohabiting without being married and 1.3% were single, whereas in 1.1% of the homes one of the parents had died.

In relation to the educational level of mothers of adolescents, 9.3% did not have primary education, 39.1% had primary studies, 15.3% had finished high school, 19.6% had completed Vocational training and 16.7% had university studies. As for the fathers, 10.5% did not have a primary education, 41.2% had primary education, 14.6% had finished high school, 17.9% had completed Vocational training and 15.7% had started university studies. The 3.8% and 1.2% of parents of adolescents in this study presented severe physical and psychological illnesses respectively, while 4.9% and 1.1% of mothers have physical and psychological illnesses.

Instruments

In order to collect the socio-demographic data of the participants, a set of questions were asked concerning the city of origin, sex, age, importance allocated to studies (evaluated through 5 items answered via a Likert scale) and the existence of any type of drug and/or alcohol consumption by the participant. Another set of questions was asked regarding their parents: the country of origin of the father and mother, excessive consumption of alcohol or any drug use, educational level, marital status and existence of any serious physical or psychological illnesses (temporary or chronic, which have had a significant impact on their quality of life; e.g., cancer, depression).

Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R; Derogatis, 2001). The SCL-90-R is a questionnaire for the self-assessment of a spectrum of psychopathology dimensions, both in psychiatric patients and among the healthy population. The SCL-90-R asks the individual about the existence and intensity of a series of psychiatric and psychosomatic symptoms, assessing the intensity of each symptom on a 5-point Likert scale: 1 ("Not at all"), 2 ("Very little"), 3 ("A little"), 4 ("Enough") and 5 ("A lot"). In this study, 65 items grouped into 7 dimensions of symptoms were used: obsessions and compulsions (e.g., "I had unpleasant thoughts that did not leave my head"), interpersonal sensitivity (e.g. "I criticize others"), depression (e.g "I don't have a lot of energy"), anxiety (e.g. "Nervousness"), hostility (e.g. "I feel angry, moody"), paranoid ideation (e.g. "I feel that others are guilty of what is happening to me") and psychoticism (e.g. "I feel that others can control my thoughts"). An item referring to loss of interest in sexual relationships was removed from the final list due to the age of a relevant number of participants. This instrument in the present study shows a high reliability with a Cronbach alpha coefficient of .79, .76 and .80 for the scales of psychoticism, obsession and interpersonal sensitivity, respectively, and of .87, .82, .78 and .75 for the scales of depression, anxiety, hostility and paranoid ideation.

Child-to-Parent Aggression Questionnaire (CPAQ; Calvete et al, 2013). The CPAQ evaluates CPV through 20 parallel items: 10 referred to the father and another 10 referred to the mother. In each block of 10 questions, 7 describe psychological aggressions (e.g., "Insult, and threaten to hit the parent"), while the other 3 items describe physical assaults (e.g., "Strike with something that can cause damage or kick"). The adolescents indicate how often they have committed these behaviors against the father or the mother in the last year using a 4-point Likert scale: 0 ("Never"), 1 ("It has occurred once or twice"), 2 ("It has occurred around 3 to 5 times") and 3 ("It has occurred 6 times or more"). The item "You have taken money from your father/mother without permission", originally part of the psychological aggression scale, was analyzed independently in order to assess the existence of economic violence. On the other hand, a new item was added to the psychological CPV scale: "You have broken valuable and precious objects belonging to your father/mother with intent to annoy them". The Cronbach's alpha coefficients in this study were .71 and .74, for physical CPV toward parents and .73 and .74 for psychological CPV toward parents, respectively.

Procedure

Firstly, permission was requested from the different educational centers in order to be able to administer the survey in these centers. In each center, a first contact was made with the Orientation Department in order to communicate the nature and the objectives of the study, later requesting through such department the necessary permissions to the School Council of each center. All the centers that were offered the opportunity to collaborate in the research responded affirmatively. The questionnaire was applied in 11 public centers in the provinces of Málaga and Granada.

Participants were informed that participation in the questionnaire was entirely voluntary and anonymous. The confidentiality of the data was guaranteed through the assignment of a numerical code to each questionnaire. Only 1.6% (of the total sample) did not complete the questionnaires, for various reasons such as being foreigners and not understanding Spanish correctly, refusing to complete it or not filling in some of the scales. These questionnaires were discarded from the final sample, which was composed of 855 participants. After completing the questionnaires, the authors proceeded to carry out a conference on all the topics covered in the research in each of the classrooms, in which all the students' doubts were resolved.

In this study, no restrictive criteria have been used to assess the existence of CPV. It has been evaluated in the form of a scale, through which the frequency with which the children perform aggressive behaviors towards their parents was evaluated. The objective of this was to take into account all the responses to the CPV scale, both low and high incidence.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyzes of the present ex post facto study were carried out using the statistical package SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences), version 20. Multiple hierarchical linear regression analyzes were used (with a probability for input F of p = .05 and output of p = .10), in order to analyze both the relationship between psychopathology and CPV and the moderating role of participants' sex in such relationship.

Following the usual protocol (Cohen & Cohen, 1983), centered scores were used in order to avoid multicollinearity problems. The interaction analyzes were carried out using the Aiken and West (1991) procedure. Two multiple hierarchical regression analyzes were performed to test the hypothesis that the relationship between the scales of SCL-90-R and total CPV towards the father and the mother vary according to the sex of the participants. The existence of a moderating relationship is demonstrated through the existence of a significant interaction between the proposed moderator (the participant's sex) and the independent variables (psychoticism, obsession, ideation, anxiety, hostility, sensitivity and depression), using the total CPV towards the father and towards the mother as dependent variables. The interactions between the SCL-90-R psychopathology scales and the child's sex were assessed by performing three-step regressions. In 2 multiple hierarchical regressions, one for total CPV towards the father and the other for total CPV towards the mother, control variables (age, sex of the participant, importance allocated to studies and drug consumption of the participant and his/her parents) were introduced in a first step, the 7 scales of psychopathology in a second step, and the interactions (the products of multiplying the scales of psychopathology by the sex of the participant) in a third step.

Results

Tables 1 and 2 show the descriptive data of the sociodemographic variables of the present study, the different SCI-90-R scales, the CPV modalities (physical, psychological, economic and total), alcohol and drug consumption and the importance allocated to studies.

The results show that the most frequent type of CPV is a psychological violence, both towards the mother and the father, M = .59, SD = .50 and M = .49, SD = .49, respectively. In addition, the results show that minors carry out more violent behaviors in general towards their mothers than towards their fathers, with M = .44, SD = .39 and M = .36, SD = .37, respectively.

The percentage of participants who committed severe assaults on their parents was also calculated. Following Calvete et al.'s (2013) suggestions, the percentage of participants who reported having carried out threatening behavior, insults, blackmail, doing something to annoy their parents, disobeying an important order or taking money without their permission in more than 6 occasions were considered as serious psychological and economic aggression. In order to evaluate severe physical aggression, the percentage of cases that reported physical aggression at least 3-5 times was considered. In this way, 21.7% acknowledged committing serious psychological aggressions towards their father and 27% towards their mother. In relation to serious physical aggression, 2.4% of participants acknowledged that they had committed them towards their parents and 2.3% towards their mothers. Finally, with regard to economic violence, 4.2% had committed them towards their fathers and 5.6% towards their mothers.

Predictor factors of child-to-parent violence

First, an analysis of the CPV predictor variables was performed using 8 linear multi-step regressions for total, psychological, physical and economic CPV, both for the father and for the mother. In a first step, the control variables (sex and age of the participant, drug consumption of the father, the mother and the participant and the importance the participant allocates to study) were introduced and in a second step, the 7 psychopathology scales of the SCL-90 -R were administered.

In relation to the total CPV towards the father, results yielded a multiple linear regression model with adjusted R2 = .21, F (13, 806) = 16.96, p < .001. This model shows that the importance that participants allocate to the studies, β = -.156, p < .001, drug consumption by the participants, β =.141, p < .001, and their age, β = .067, p < .05 were predictors of total CPV towards the father. With respect to scales of the SCL-90-R, the multiple regression model shows that the paranoid ideation scales, β =. 116, p < .05, depression, β = -.179, p <. 05, and hostility, β = .284, p < .001, predicted this type of violence.

The regression analysis of the total CPV towards the father was repeated by dividing the sample into 3 age groups: from 13 to 15 years of age, from 16 to 18, and from 19 to 21 years of age. Regarding the first age group (13-15), a regression model with adjusted R2 = .20 (p < .001) was found, with only the importance allocated to studies, β = -.251,p < .001 and hostility, β =.202 showing significance, p < .01. In relation to the 16-18 age group, the adjusted R2 regression model = .23 (p < .001) showed that CPV was related to the importance allocated to studies, β = -.10, p < .05, drug consumption on behalf of the participants, β =.178, p < .001, interpersonal sensitivity, β =. 168, p < .05, depression, β = -.260 ,p <. 001, and hostility, β = .347, p < .001. However, in the third age group (18-21) the regression model was not significant (adjusted R2 = -.11, p = .918).

With regard to the total CPV directed towards the mother, the multiple linear regression model with adjusted R2 = .26, F (13, 811) = 22.27, p < .001, showed a relation with the female sex, β = .084, p < .05, the importance that children allocate to studies, β =-.159, p < .001, drug consumption on behalf of the participant, β= .177, p < .001, and their age, p = .075, p < .05, in addition to paranoid ideation, β = .106, p <.05, depression, β -.173, p <.01, and hostility, , β - .335, p < .001.

Once again, the regression analysis relative to the total CPV towards the mother was repeated by dividing the sample into 3 age groups. A regression model with adjusted R2=.20 (p < .001) was found in relation to the age group of 13-15 years, with only the importance allocated to studies, β = -.194, p < .001 and hostility, β =.290, p < .001 yielding significance. In relation to the 16 to 18 years age group, the regression model with adjusted R2 - .27 (p < .001) showed that CPV was related to the female sex, β - .09, p < .05, importance allocated to studies, β = -.147, p < .001, drug consumption on behalf of the participants, β =.176, p < .001, depression, β = -.219, p < .01, hostility, β - .346, p <. 001, and paranoid ideation, β - .120, p < .05. However, as was the case of the CPV towards the father, the regression model was not significant (adjusted R2= .13, p = .744) in the 18-21 age group.

Regarding the psychological CPV towards the father, the multiple linear regression model with adjusted R2 = 0.186, F (13, 813) = 15.56, p < .001, showed that it was related to the importance allocated to studies, β= -.136, p < .001, drug or alcohol consumption on behalf of the participant, β= .120, p < .001, and their age, β = .067, p < .05. With regard to the scales of the SCL-90-R, the model showed that paranoid ideation, β = .136, p < .05, depression, β = -.161, p <.01, and hostility, β = .278, p < .001 predicted this type of violence.

In relation to the psychological CPV towards the mother, it was found that sex, β= .089, p < .01, the importance allocated to studies, β = -.143, p < .001, drug consumption on behalf of the participant, β = .156, p < .001, and their age, β = .085, p < .01, were related to this violence. In relation to the psychopathology scales, the psychological CPV towards the mother was related to interpersonal sensitivity, β = .112, p < .05, depression, β = -.154, p < .01, and hostility, β = .323, p < .001. This model explained 23% of the variance in psychological violence towards the mother, with F (13, 832) - 20.39, p < .001. It should be noted that although a significant relationship with the paranoid ideation scale was not found, it showed a tendency towards significance (β= .100, p = .053).

In relation to the physical CPV towards the father, an adjusted R2 = .040, F (13, 830) = 3.15, p < .001 was found, yielding significant relationships only with the psychoticism scales, β=.128, p < .05, and hostility, β = .091, p < .05. On the other hand, the multiple linear regression model for the physical CPV towards the mother, with an adjusted R2= .075, F (13, 841) - 6.33, p < .001, confirmed a relationship only with the importance allocated to studies, β = -.096, p < .05, and the hostility scale, β = .199, p < .001.

With regard to the economic CPV towards the father, the importance that children allocate to studies, β= -.177, p < .001, drug consumption on behalf of the participant, β= .208, p < .001, and drug consumption on behalf of the father, B=.066, p <.05, referring to control variables, and hostility, β = .210, p < .001, interpersonal sensitivity, β = .131, p < .05, psychoticism β = .120, p < .05, and depression, β = -.198, p < .05, with respect to psychopathology variables predicted this type of violence, with adjusted R2= .122, F (13, 827) - 9.65, p < .001.

Finally, the variables related to the economic CPV directed towards the mother were the importance that children allocate to studies, β = -.137, p < .001, drug consumption on behalf of the participant, β =.179, p < .001, hostility, β = .220, p < .001 psychoticism, β = .137, p < .05) and depression, β = -.182, p < .01, with an adjusted R2 = .146, F (13, 838) = 10.47, p < .001.

Interactions between psychopathological symptomatology and the sex of participants

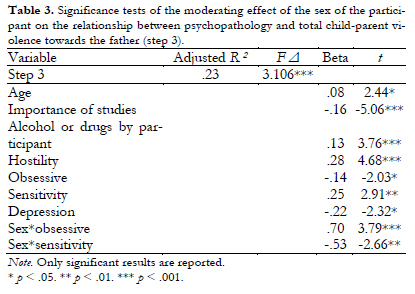

Two multiple hierarchical regression analyzes were performed to test the hypothesis that the relationship between the scales of the SCL-90-R and the total CPV towards the father and the mother vary according to the sex of the participant. Regarding the total CPV towards the father, when the interactions of the SCl-90-R scales with the participant's sex were introduced in the regression analysis, the percentage of variance increased to 23% (the third step of this regression analysis is shown in Table 3). In this case, there were significant interactions between obsession scales, with β = .693, p < .001 and sensitivity, with β = -.536, p < .01 and the sex of the minor.

Regarding the total CPV towards the mother, when the interactions of the SCl-90-R scales with participant's sex were introduced as predictors, the percentage of explained variance also increased to 29% (Table 4). This result supports the existence of an interaction between psychopathology and the sex of the participants; specifically, the interaction between obsession scales, β = .509, p < .01, sensitivity, β = -.752, p < .001, and paranoid ideation, β = .378, p < .05, with the sex of the child.

After finding that the relationship between the psychopathology scales and the total CPV towards the father and the mother varied according to the sex of the participants, 2 independent regression analyzes were performed (one for the total CPV towards the father, and another for the total CPV towards the mother) to determine the pattern of moderation relationships. The psychopathology variables that interact with the sex of the participants were introduced as independent variables, dividing the sample according to the sex of the minors.

Regarding the total CPV towards the father, the interpersonal sensitivity scale was found to be positively related in the case of boys with a value of β = .262, p < .001, but not in the case of girls, while in the case of the obsession scale, this relationship is inversely related, being positive only in the case of girls with β = .247, p < .001.

Finally, in relation to the total CPV towards the mother, a positive relationship was found with the interpersonal sensitivity scale, β = .220, p < .01, in the case of boys, while in the case of girls, this relationship was negative, with β = -.219, p < 01. On the other hand, the paranoid ideation, β = .373, p < .001, and the obsession, β = .212, p < .001, scales presented a significant positive relationship with the total CPV towards the mother in the case of the girls, whereas in the case of the boys, this relation was not significant.

Discussion and conclusions

The present study provides data that can contribute to clarify the relationships between the psychological variables of the aggressor and the different types of child-to-parent violence. Firstly, the main objective of the study was to analyze the correlations between the different SCL-R-90 scales and the different types of CPV towards the father and the mother separately, controlling for the variables of sex and age of the participants, importance allocated to studies and drug consumption by family members. The second objective was to analyze the interactions between the sex of the participants and the psychopathology scales, hypothesizing that sex affects the relationship between psychopathology and aggressive behavior of minors towards their parents.

The results of the present study have shown that the importance that the participants allocate to their studies is a protecting factor when committing aggressive acts towards the parents, being physical violence towards the father the only type of CPV not related to it. Álvarez-Cienfuegos and Egea's (2003) review of studies on youth violence confirms this result, by considering that the interest and academic expectations of minors constitute a protection factor on youth violence.

As in the case of the importance allocate to studies, participants' drug consumption was related to all types of CPV except for physical violence towards the father and the mother. The importance of this variable in the present study coincides with previous research (e.g., Cotrell, 2001; Ibabe & Jaureguizar, 2011), which states that drug consumption by minors is a common factor in cases of aggression towards parents. However, there was no relationship between alcohol or drug consumption on behalf of the parents and the CPV. It is possible that this lack of relationship with the commission of CPV is due to a misperception about such consumption by the participants.

Regarding the sex of the participant, a relationship was found with the total and psychological CPV towards the mother, indicating a greater probability of committing these types of violence by girls rather than boys. International studies have established that between 50% and 80% of CPV is committed by boys (Cottrell & Monk, 2004; Romero, Melero, Cánovas & Antolín, 2007; Walsh & Krienert, 2007). However, when physical violence is analyzed separately from psychological violence (the most prevalent type of violence in the present study), recent research has found no difference between boys and girls regarding rates of emotional violence (Ibabe, Jaureguizar y Bentler, 2013), and even some studies have found a greater frequency of verbal and emotional violence among girls (Calvete et al., 2013). Regarding the last of the control variables, the age of the participant, a positive relationship was found with the total and psychological CPV, both towards the father and the mother.

In relation to the psychopathology variables, a positive relationship was found between the hostility score and the CPV in all its forms (psychological, physical, economic and total, both towards the father and the mother). Based on the definition given by Derogatis (2001) on the scale of hostility (negative affects of anger), it can be concluded that the fact that the child is constantly angry, in a bad mood and hostile increases the probability of responding to intra-family conflicts in a violent or aggressive way.

In relation to the depressive symptomatology scores, a negative relationship was found between these and all CPV types, with the exception of physical violence towards the father and the mother. One possible explanation for this negative association between depression and CPV is that the child, when presenting depressive symptoms such as lack of motivation, low vital energy and dysphoric state of motivation, is isolated from the family environment and, therefore, will not perform aggressive behaviors towards his/her parents. However, comparing these data with Calvete et al.'s (2011) research, the results are conflicting, as these authors have found that depressive symptoms are a predictor of CPV.

With respect to the paranoid ideation scale, a relation with the psychological and the total CPV towards the father and the mother was found. Derogatis's (2001) definition of the paranoid ideation scale, characterized by fear of loss of autonomy or control, it agrees with the definition of CPV, which states that the minor commits criminal behavior to achieve some control, power and domain in order to achieve its objectives or purposes (Aroca, 2010). Despite this, there was no relationship to physical or economic violence.

In relation to the scale of interpersonal sensitivity, only a relationship with the psychological violence towards the mother and economic violence towards the father were found. A theoretical explanation on the association between interpersonal sensitivity and these types of CPV could be, based on the definition of interpersonal sensitivity offered by Derogatis (2001), that when the minor has feelings of inferiority and inadequacy, mainly among his fellows, he/she discharges his/her anger and feelings towards his/her parents, as they have a greater relationship with them or they do not feel inferior to them and they need to recover the determined self-esteem that they have lost with their peers.

Furthermore, a relationship between psychoticism scores and physical aggression towards the father was found, which is the only variable, along with hostility, that has predicted this type of aggression. It is probable that the small percentage of variance explained in this modality of CPV is due to the reduced presence in this study of children who commit acts of physical violence towards their parents, due to the type of sample used. In fact, prior research has shown how the prevalence of this type of child-to-parent violence is significantly higher in forensic population samples than in samples from the general population (Kennedy, Edmonds, Dann & Burnett, 2010).

Regarding the obsession scale, no relationship was found with CPV in any of its forms. However, subsequent analyzes showed that, although obsessive symptoms did not relate to the commission of total CPV towards the father or the mother in the case of boys, in the case of girls, there was a relationship with both types of violence. It is possible that this psychopathological symptom causes a greater frustration among girls than among boys, with such frustration provoking acts of violence. Finally, no relationship was found between the last of the scales, anxiety, and any of the CPV forms. According to this result, the presence of fears or signs such as tension or panic attacks is not related to the commission of violence towards parents.

When regression analyzes regarding the total CPV were performed separately for each of the age groups, it was found that the age group of participants between 16 and 18 years was where the psychopathological symptomatology had a greater predictive power, followed by those in the range of 13 to 15 years of age. However, neither the total

CPV towards the father nor towards the mother were found to be related to psychopathology among those older than 18 years of age; although this last result could be due to the reduced number of participants in this age range (47).

The interaction between the psychopathology scales and the sex of the participants was also analyzed, confirming the hypothesis that the effects of psychopathology on the commission of CPV towards the father and the mother depend on the sex of the aggressor. Firstly, in relation to the total CPV towards the father, a relationship was found with interpersonal sensitivity in the case of boys, whereas this relation was not significant in the case of girls. However, regarding the obsession scale, the opposite pattern was obtained, with this scale being related to the total CPV towards the father in the case of girls but not in the case of boys.

In relation to the total CPV towards the mother, a positive relationship was found with the interpersonal sensitivity scale in the case of boys, whereas in the case of girls the relation was negative. That is, boys who have high interpersonal sensitivity, more often commit total CPV to the mother, whereas in the case of girls the pattern is opposite. One possible explanation for these results would be that boys become frustrated by feeling inferior to their peer group, and thus, attack their parents as a strategy to deal with that accumulated tension. However, girls who are frustrated by their sense of inferiority, use the strategy of seeking emotional support in their parents. In short, they present the same problem, but use different coping strategies. Finally, the paranoid ideation and obsession scales have a significant positive relationship with the total CPV towards the mother in the case of girls, whereas in the case of boys, this relationship was not significant.

This study presents some limitations that must be taken into account when interpreting the results. First, the correlational design of the study precludes causal interpretations. The present findings should be replicated through longitudinal designs, which would allow us to examine the strength and directions of causal relationships (Cantón-Cortés y Cortés, 2015).

Another limitation of this study is the reduced number of minors who confirm that they perform acts of special gravity, especially in relation to physical aggression, which must be taken into account when interpreting the results on this type of CPV. It is probable that the small percentage of explained variance in this type of CPV is due to the small presence in this study of children who commit acts of physical violence towards their parents. Likewise, as it is a normative sample, not only the acts of physical violence but also the values of the psychopathological symptoms found have been low. However, the prevalence of severe physical aggression found in this study is practically identical to that found by other studies that have used the same instrument to assess aggression towards parents (e.g., Calvete et al., 2013).

Finally, another limitation refers to the fact of having evaluated some of the family variables, such as the consumption of alcohol or drugs on behalf of parents, through the participants. It is possible that the participants in the study did not know or did not have an exact idea about certain characteristics of their parents, which may have affected the results of this study.

However, in spite of these limitations, the present study contributes to clarify the knowledge on the psychological profiles characteristic of the different types of CPV and shows the role of drug or alcohol consumption on behalf of the minor, the importance they allocate to studies, and the presence of certain psychopathologies, mainly in relation to the scales of hostility, psychoticism and depressive symptomatology. Complementarity and depending on the type of CPV analyzed and the sex of the participants, an association between CPV and paranoid ideation scales, interpersonal sensitivity and obsessive-compulsive symptomatology was found.

References

1. Alvarez-Cienfuegos, A., & Egea, F. (2003). Aspectos psicológicos de la violencia en la adolescencia (Psychological aspects of adolescent violence). Estudios de Juventud, 62, 37-44. [ Links ]

2. Aroca, C. (2010). La violencia filio-parental: una aproximación a sus claves. Tesis Doctoral (Child to parent violence: an approximation to its key aspects. Doctoral dissertation). Universidad de Valencia. [ Links ]

3. Aroca-Montolío, C., Lorenzo-Moledo, M., & Miró-Pérez, C. (2014). La violencia filio-parental: un análisis de sus claves (Child to parent violence: an analysis of its key aspects). Anales de Psicología, 30, 157-170. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.30.1.149521. [ Links ]

4. Calvete, E., Gámez-Guadix, M., & Orue, I. (2014). Características familiares asociadas a la VFP en adolescentes (Family characteristics associated to CPV in adolescents). Anales de Psicología, 30, 1176-1182. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.30.3.166291. [ Links ]

5. Calvete, E., Gámez-Guadix, M., Orue, I., González-Diez, Z., López de Arroyabe, E., Sampedro, R., Pereira, R., Zubizarreta, A., & Borrajo, E. (2013). The Adolescent Child-to-Parent Aggression Questionnaire: An examination of aggression against parents in Spanish adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 36, 1077-1081. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.08.017. [ Links ]

6. Calvete, E., Orue, I., & Gámez-Guadix, M. (2013). Child-to-parent violence: Emotional and behavioral predictors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28, 754-771. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0886260512455869. [ Links ]

7. Calvete, E., Orue, I., & Sampedro, R. (2011). Violencia filio-parental en la adolescencia: Características ambientales y personales (Child to parent violence in adolescence: Environmental and personal characteristics). Infancia y Aprendizaje, 34, 349-363. http://dx.doi.org/10.1174/021037011797238577. [ Links ]

8. Cantón-Cortés, D., & Cortés, M.R. (2015). Consecuencias del abuso sexual infantil: una revisión de las variables intervinientes (Child sexual abuse characteristics: a review of intervening variables). Anales de Psicología, 31, 552-561. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.31.2.180771. [ Links ]

9. Contreras, L., & Cano, M.C. (2015). Exploring psychological features in adolescents who assault their parents: A different profile of young offenders? The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology, 26, 224-241. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2015.1004634. [ Links ]

10. Coogan, D. (2012). Child-to-parent violence: Challenging perspectives on family violence. Child Care in Practice, 17, 347-358. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13575279.2011.596815. [ Links ]

11. Cottrell, B. (2001). Parent abuse: the abuse of parent by their teenage children. The family violence prevention unit health. Canada. [ Links ]

12. Cottrell, B., & Monk, P. (2004). Adolescent-to-parent abuse: A qualitative overview of common themes. Journal of Family Issues, 25, 1072-1095. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0192513X03261330. [ Links ]

13. Cuervo A.G., & Rechea C.A. (2010). Menores agresores en el ámbito familiar. Un estudio de casos (Under age perpetrators in the family unit. A cases study). Revista de Derecho Penal y Criminología, 3, 353-375. [ Links ]

14. De la Torre, M.J., García M.C., de la Villa M., & Casanova, P.F. (2008). Relaciones entre violencia escolar y autoconcepto multidimensional en adolescentes de ESO (Relationships between school violence and multidimensional self-concept among high school adolescents). European Journal of Education and Psychology, 2, 57-70. [ Links ]

15. Derogatis, L.R. (2001). Cuestionario de 90 síntomas (SCl-90-R) (Symptom Checklist-90-R (SCH90-R)). Madrid: TEA Ediciones. [ Links ]

16. Estévez, E., Murgui, S., & Musitu, G. (2009). Psychosocial adjustment in bullies and victims of school violence. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 24, 473-483. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF03178762. [ Links ]

17. Gallagher, E. (2008). Children's violence to parents: a critical literature review. Monash University, Melbourne. [ Links ]

18. Gámez-Guadix, M., & Calvete, E. (2012). Violencia filio-parental y su asociación con la exposición a la violencia marital y la agresión de padres a hijos (Child to parent violence and its association to parental violence exposition and parent to children aggression). Psicothema, 24, 277-283. [ Links ]

19. García-Linares, M.C., García-Moral, A.T., & Casanova-Arias, P.F. (2014). Prácticas educativas paternas que predicen la agresividad evaluada por distintos informantes (Paternal parenting styles that predict aggressivity assessed by several informants). Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 46, 198-210. [ Links ]

20. Ibabe, I. (2015). Family predictors of child-to-parent violence: the role of family discipline. Anales de Psicología, 31, 615-625. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.31.2.174701. [ Links ]

21. Ibabe, I., & Jaureguizar, J. (2011). ¿Hasta qué punto la violencia filio-parental es bidireccional? (Is child to parent violence bidirectional?) Anales de Psicología, 27, 265-277. [ Links ]

22. Ibabe, I., Jaureguizar, J., & Bentler, P.M. (2013b). Protective factors for adolescent violence against authority. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 16, 1-13. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2013.72. [ Links ]

23. Kennedy, T.D., Edmonds, W.A., Dann, K.T.J., & Burnett, K.F. (2010). The clinical and adaptive features of young offenders with histories of child-parent violence. Journal of Family Violence, 25, 509-520. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10896-010-9312-x. [ Links ]

24. Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J., & Neidig, P. (1995). Violence backgrounds of economically disadvantaged youth: Risk factors for perpetrating violence? Journal of Family Violence, 10, 379-398. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02110712. [ Links ]

25. Laurent, A., & Derry, A. (1999). Violence of French adolescents toward their parents. Characterises and context. Journal of Adolescent Health, 2, 21-26. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(98)00134-7. [ Links ]

26. Lyons, J., Bell, T., Fréchette, S., & Romano, E. (2015). Child-to-Parent Violence: frequency and family correlates. Journal of Family Violence, 30, 729-742. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10896-015-9716-8. [ Links ]

27. Nowakowski-Sims, E., & Rowe, A. (2015). Using trauma informed treatment models with Child-to-Parent Violence. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 8, 237-244. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s40653-015-0065-9. [ Links ]

28. Romero, F., Melero, A., Cánovas, C., & Antolín, M. (2007). La violencia de los jóvenes en la familia: Una aproximación a los menores denunciados por sus padres. (Juvenile violence in the family: An approximation to minors reported by their parents). Barcelona: Centro de Estudios Jurídicos y Formación Especializada. [ Links ]

29. Routt, G., & Anderson, L. (2011). Adolescent violence towards parents. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 20, 1-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2011.537595. [ Links ]

30. Tobeña, R. (2012). Niños y adolescentes que agreden a sus padres: Análisis descriptivo. Tesis doctoral. (Children and adolescents that assault their parents. Doctoral dissertation). Universidad de Zaragoza. [ Links ]

31. Walsh, J.A., & Krienert, J.L. (2007). Child-parent violence: An empirical analysis of offender, victim and event characteristics in a national sample of reported incidents. Journal of Family Violence, 22, 563-574. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10896-007-9108-9. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

David Cantón-Cortés.

Departamento de Psicología Evolutiva y de la Educación,

Facultad de Psicología,

Universidad de Málaga,

Campus de Teatinos,

29071, Málaga (Spain).

E-mail: david.canton@uma.es

Article received: 20-10-2015;

Revised: 26-03-2016;

Accepted: 01-05-2016