Introduction

Anxiety is defined as a state of tension given to possible danger situations which includes cognitive elements as well (Chansky, 2009). Although childhood era is full of developmental anxieties, if they are experienced too intensely and distort functionality or if they are experienced for too long, they are called anxiety disorder (APA, 2014). Anxiety disorders have negative effects on the life of individuals (Karakaya & Öztop, 2013). Anxiety symptoms which appear in children and adults show differences. Somatic complaints (excessive sweating, stomachache, intestinal disorders etc.) are seen more frequently in children than adults (Karakaya & Öztop, 2013). One study on the prevalence of anxiety disorders in children found that 26.6% of children experienced anxiety, 15.8% of children suffered from unique phobia, 6.6% suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder (anxiety disorder developing as a result of traumatic experiences) and 5.6% suffered from separation disorder (Abbo et al., 2013). Childhood era disorders can lead to more serious problems in following ages unless they are treated. For this reason, application of effective intervention programmes in childhood era gains importance. Each intervention programme must include its own cultural structure (Naeem et al., 2015). Examination of the historical past which can affect culture and current conditions becomes importance in the design of an intervention programme adapted to the culture. Along with the impact of eastern civilization, Cyprus bears the marks of western civilization as well, as it was home to several civilizations from the past to the present. The island experienced several wars throughout centuries due to its strategic importance. In 1878 Great Britain made a treaty with Ottoman Empire and hired the island. In 1914 England annulled the contract unilaterally and possessed the administration of Cyprus until 1960. Turks and Greeks united in their uprising against British administration despite differences in ideology. After the bi-communal uprisings which intensified in 1958, the two largest ethnic groups in Cyprus, Turks and Greeks, founded the Republic of Cyprus in 1960. After this foundation, conflicts erupted in 1963 which would continue for 11 years between Cypriot Greeks and Turks. Volkan (2008) claims that the conflicts which continued for 11 years caused trauma in Cypriot Turks and the intervention of Turkey in 1974 caused trauma in Cypriot Greeks. During these conflicts several people from both ethnic groups lost their lives and were forced to migrate from the places where they were born and raised. The existence of cultural similarities between two ethnical groups is seen as the reason of ethnic origin conflicts. Turks who migrated to the north after 1974 burnt the clothes left by Greeks as an unconscious process of catharsis (. Volkan (2008). Volkan (2001) emphasises the existence of selected trauma. Major group trauma/selected trauma is defined as one group imposing planned loss, shame and helplessness on another group. Such huge losses prevent the group members from experiencing the process of mourning. This mourning which was not experienced is transferred to future generations consciously or sub-consciously and the emotions that the conflict will be resolved by the new generation is shared among generations (Volkan, 2009). As an inter-generation transfer, selected trauma causes the future generations to feel that people who made their ancestors suffer are “others”. In addition to the experience of trauma and mourning by the new generation, images are also transferred to the new generation which become a part of the identity of that new generation (Juni, 2016).

Experienced traumas are transferred to next generations (Giladi & Bell, 2012). First studies on intergenerational transfer were conducted on the Jews who survived Second World War and their children. Although the Jews who survived concentration camps did not talk about the camp, post-trauma stress disorders are reported in 3rd generation (Starman, 2006). Van Ijzendoorn, Bakrmans-Kranenburg & Sagi-Schwartz (2003) claim that the trauma skips a generation and appears in the third generation. In addition, it is reported that second and third generations suffer from anxiety disorders and depression (Ben-Ezra, Palgi, Hamama-Raz & Shrira, 2015; Sagi-Schwartz, Ijzendoorn & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 2008). The relation of the culture with anxiety disorders are displayed in intergenerational and intercultural studies and it is stated that such factors as migration, economic changes, acts of nature and war affect both that generation and next generations (Snyder, Bullard, Wagener, Leong, Snyder & Jenkins, 2009).

The island of Cyprus is still divided into two with Turks living in the north and Greeks living in the south. In 1983 Cypriot Turks declared Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) and founded their own administrative system. However, TRNC is not a recognized state. The isolations, embargoes and non-recognized identities of Cypriot Turks cause them to suffer from psychological problems (Volkan, 2008). Material resources experienced in the war and in the adaptation process to the new life which followed, Cypriot Turks did not receive any psychological support for solving their problems. The war which continued for 11 years and the migration which followed as well as the mourning for the lost have not been subject to any study. There are individuals who came from Turkey and settled in Northern Cyprus after 1974 and there are others who migrated from several countries due to warfare after the foundation of TRNC in 1983. Therefore, children living in Cyprus were exposed to several factors which could affect their anxiety disorders such as war, migration, economic problems and identity issues. As the 4th generation, the traumas transferred by their ancestors can lead to anxiety disorders and programmes should be developed for their treatment.

Gradual treatment approaches provide advantage due to their elasticity; they also increase effectiveness as they include psycho-education (Rozenman & Piacentini, 2016). Psycho-education includes cognitive and behavioural elements (Beck & Dozois, 2011). It can be applied in different cultures, adjusted to reflect individual needs, and allows for the person to self-educate with its strong therapeutic relation (Cohen, Mannarino & Staron, 2006). In BDT programme the child learns techniques and skills for eliminating the symptoms of anxiety (Horowitz, 2017). In another study, a class-focused BDT programme which took 4 weeks was applied to children between ages of 9 and 12 and it was observed that their anxiety symptoms disappeared (Yeo, Goh & Liem, 2016). Empirical studies support that BDT is effective in treating the anxiety disorders in children and teens (Tutus, Pfeiffer, Rosner, Sachser & Goldbeck, 2017; Ishikawa, Okajima, Matsuoka & Sakano, 2007; Şar, Barut & Koç, 2007). The importance of school-based programmes is emphasised for anxiety (Geroski & Kraus, 2012). Ease of transportation, the solution of time problems and lower material expenses make this application more advantageous (Miller et al., 2011). School-based anxiety programmes consist of the coping strategies and relaxation techniques of BDT as well as cognitive restructuring and modelling techniques (Shaker-Naeeni & Governder, 2014). A meta-analysis study conducted on school-based anxiety intervention programmes treating anxiety of children and adolescents reported that the effectiveness of these programmes was between 0.11 and 1.37 (Neil & Christensen, 2009). Seventy-eight percent of these programmes are based on Cognitive Behavioralist Therapy (BDT). In addition, it is also known as an effective method in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (McMullen, O’Callaghan, Shannon, Black & Eakin, 2013). In this direction, the purpose of the study in this direction is to examine the effectiveness of the school-based cognitive behaviour program on the reduction in anxiety levels of children at 9-10 years of age. Methods

Method

Research Design

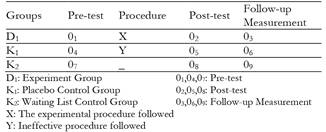

The study employed pre-test/post-test experimental pattern with control group (Table 1). An experiment group and two control groups were used in the study in order to test the effectiveness of the intervention programme.

Participants

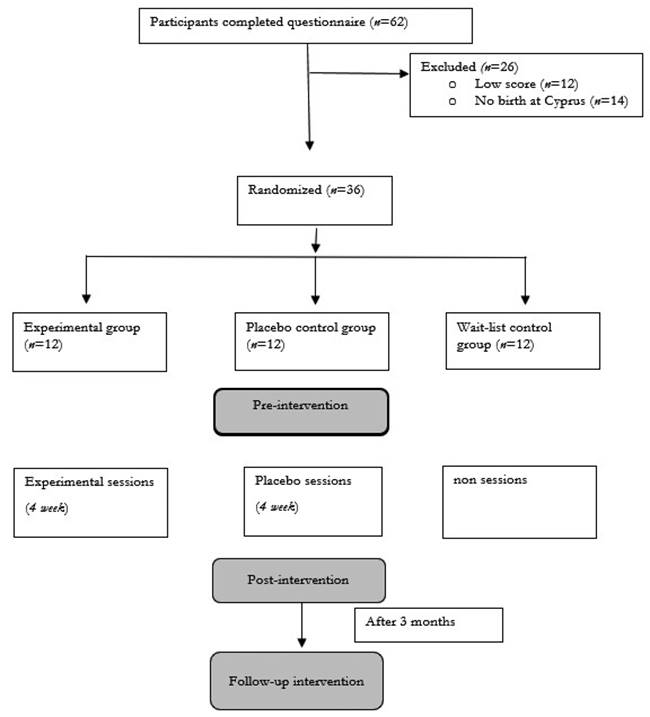

The participants who took part in this study consist of male and female students at 4th grade (9-10 years of age) who are enrolled at elementary schools under Ministry of National Education of Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. The study was conducted on 36 participants who were divided into 3 groups of 12 pupils (7 girls, 5 boys), one of which was experiment group and two of which were control groups.

Procedure

Permission was obtained from MEB for determination of the participants of the study. The facilities of the school and voluntary support from teachers and parents were taken into consideration in the selection of school. Preliminary interview was conducted with the principal and 4th grade teachers of a public school. The conference hall of the school which also had a stage was put at the disposal of the researcher. Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale was applied to the 4th grade students of the school (N = 62).

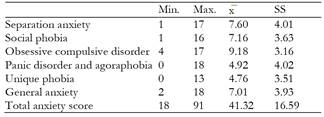

The mean of the anxiety score of the application group was taken (Table 2) and the parents of students with high anxiety who received higher scores than the mean value were invited to the school in order to introduce the content of the study. Later, an informed consent form was sent to the parents through the school which included the objective, period and content in detail. Based on the informed consents of the parents who allowed for their children to participate in the study and voluntarism of the children, 36 students were included in the research (Figure 1). Four criteria were identified in the inclusion of students in the research:

Receiving anxiety score above mean anxiety score or receiving high score in any sub-dimension scale

The grandparents of students experiencing migration in Cyprus

The family having signed and sent the informed consent form

The child having accepted participating in the study

The 36 students who wanted to participate in the study were assigned neutrally in experiment and control groups each of which would consist of 12 participants. An examination of the literature shows that such variables as divorce of parents and existence of siblings is related to anxiety. Accordingly, information on the marital status of parents and existence of siblings was obtained from the participants in order to control possible confounder variables. In addition, several studies showed that anxiety was more prevalent in females. In this direction, the three groups were balanced in terms of confounder variables such as gender, marital status of parents and being the only child (5 males; 7 females).

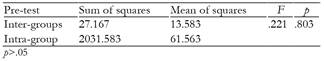

Prior to the experimental procedure, Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale was applied to both the experiment and control groups as a pre-test (Table 3). Unidirectional ANOVA was applied to test that there is no significant difference between the scores obtained by all three groups (F (2, 33) = 0.221, p >.05). An examination of the Box-M result performed for homogeneity assumption showed that it was not significant, which means that homogeneity assumption is answered (F (12, 5, 2773) = 1.623, p > .05). In this direction, it was found out that the distribution of scores was normal between three groups.

In the study the period of each session was determined as 90 minutes and consisted of 8 sessions in school environment (two sessions per week). During group sessions cognitive behavioural list elements such as psycho-education, Socratic questioning, automatic opinion capture, developing alternative opinion, role-playing, anxiety train, and modelling as well as game-based techniques such as puppet, symbolic toys, crayons and music were employed. First of all, the purpose, principles and rules of the group were given and then sessions were launched. The sessions in the programme were realised as warming, basic and closing activities. Homework was given at the end of each session. The homework assignments were discussed in the following session.

Sample session: “a piece of paper and crayons are given to the children. Each child is asked to draw a train on the paper. The anxious train will stop at each stop. These stops are transferred to the children through examples such as opinion, emotion, physical changes and behaviour stops. The meaning of each stop and how they affect each other is told based on the picture.”

Sample session: “some minor toys are given to the group members such as animals, humans, vehicles etc. Effort is paid to ensure that children express themselves more easily using the objects they choose in a dramatic game. They are asked to write their anxiety stories with these toys and tell it to the group. While they are telling the story, automatic thinking is questioned with the help of other group members.”

Breathing exercise: “children are asked to lie on their backs on soft pieces of clothes. They are asked to place their right hand on their stomach and put their left hand on their chest. They are asked to close their eyes, focus on their breathing and understand how their body changes.”

Measures

Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS)

Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS) was developed by Spence (1998) with the purpose of evaluating the different dimensions of anxiety disorders on the basis of DSM-IV criteria taking child development into consideration. In addition to child or parent form, different forms are used for 8-11 ages and 12-15 ages. The scale is a 4-Likert type scale consisting of 44 items and an open-ended question. It has such sub-dimensions as panic attack and agora phobia, separation anxiety, unique phobia, social phobia, widespread anxiety and obsessive compulsive disorder. The scale is translated into several languages and adapted to different cultures (Essau, Sakano, Ishikawa & Sasagava, 2004; Spence, Barrett & Turner, 2003; Essau, Muris & Erdener, 2002). The scale was adapted to Turkish by Direktör and Bulut Serin (2017). The Cronbach Alpha value of the scale was found as .83 and its half split value was found as .80.

Data Analysis

SPSS 20 package programme was used in the analysis of the data. MANOVA (experiment x control 1 x control 2; pre-test x post-test x following) was applied in the comparison of pre-test and post-test follow-up scores of Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale of experiment and control group. The first factor shows independent procedure groups (one experiment, one placebo, one waiting list) whereas the second factor shows repeated measurements related to independent variable (pre-test-post-test- follow-up).

Results

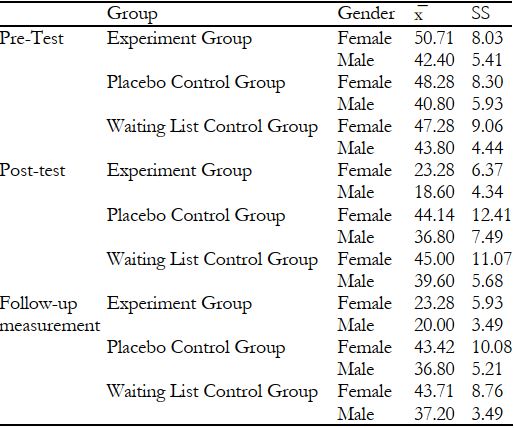

Table 4 presents pre-test, post-test and follow-up measurement scores of experiment, placebo and waiting list groups according to gender. It is seen that females received higher scores compared to males.

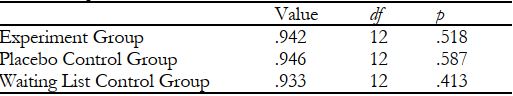

Shapiro-Wilk test was conducted in order to determine normality distribution. As presented in Table 5, it is seen that H0 hypothesis is accepted. According to this result, data are distributed normally with 95% confidence for all groups.

In order to conduct MANOVA analysis, Box test results must be examined first. An examination of Box-M results performed for homogeneity assumption did not show significant results, which means that homogeneity assumption is verified (F (12, 5, 2773) = 1.623, p >.05). It has been observed that there is no significant difference in Leven’s test (p > .05). According to the obtained results, it was determined that pre-test (F (2, 33) = 0.098, p = .907), post-test (F (2, 33) = 1.528, p = .232), and follow-up measurements (F (2, 33)= 1.302, p = .286) had homogeneous distribution. These findings show that the data have suitable psychometric properties for application of MANOVA in terms of group variable.

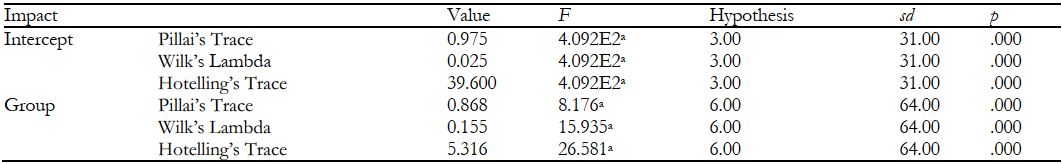

An examination of table 6 shows that Pillai’s Trace (V = .86, p < .001) Wilk’ Lambda (W= .15, p < .001) and Hotelling’s Trace (T = 5.31, p < .001) values are significant.

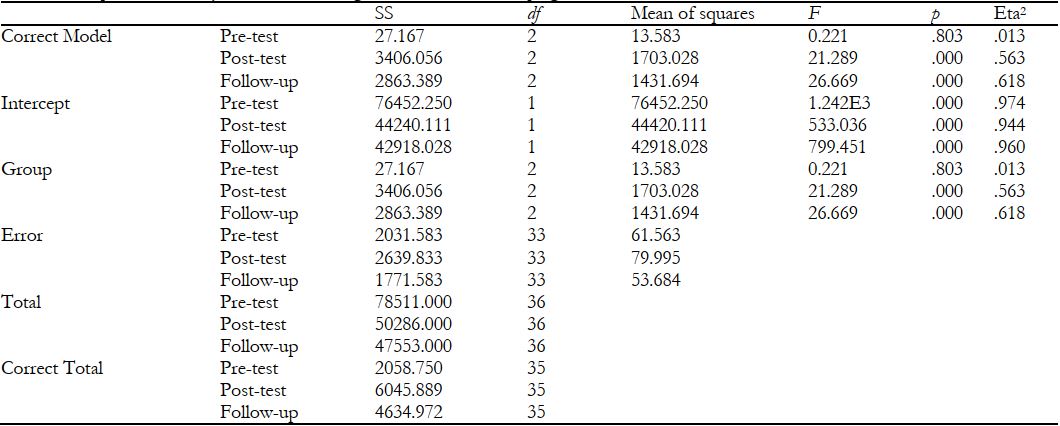

An examination of table 7 shows that the joint impact of time (pre-test, post-test and follow-up) and group (experiment-placebo-waiting list) are significant (Wilks λ=.155, F (6, 64) = 15.94; p <.01, partial ƞ2 = .563). Tukey test, which is a Post Hoc test, was performed in order to examine the time difference between three groups. As a result, the post-test (x̅ = 21.33) and follow-up measurement (x̅ = 21.92) total anxiety scores of children who participated in experiment group were found to be significantly lower compared to the children in placebo (post-test x̅ = 41.08; follow-up measurement x̅ = 40.47) and waiting list control group (post-test x̅ = 42.75; follow-up measurement x̅ = 41.00). The impact size of post-test scores was determined as 56.3% for experiment group. The impact size intervals reported by Cohen (1992) are 0.1 for low impact, 0.25 for medium impact and 0.4 for high impact. According to Cohen d index, it is observed that anxiety intervention programme has a major impact on anxiety score and that it continued its impact on follow-up measurements as well.

The results of the study show that “I can cope with my fear” programme is successful. According to ethical principles, intervention programme was applied to the participants in both placebo and waiting list control groups after the completion of the study.

Discussion & Conclusion

Applications in school settings have received increased recognition in recent years. This study found out that the programme was effective at 53% ratio. Consistent with the literature, it was displayed that a school-based anxiety programme sensitive towards culture is effective in reducing the anxiety of children. It is observed that the effectiveness levels show difference. The fact that it has a lower impact compared to the programme of Miller et al. (2008) is due to its content and possible cultural differences. Another important feature of the programme is that it was conducted on the fourth generation which experienced migration. In this direction, it is believed that the complicated structure of intergenerational transfer affected the study on anxiety level. Ben-Ben-Ezra et al. (2008) stated that the third generation of Jews who survived concentration camps displayed frequent anxiety disorders. It is believed that the high level of effectiveness of the anxiety programme is partly due to the fact that it is adapted to the culture.

School-based cognitive behavioural programme was prepared as a short-term intervention. In this direction, it was found out that the programme was effective in the short run and reduced the anxiety level of children. It is observed that the developed programme has time and group shared impact. It is believed that the children were able to adapt to the intervention programme more easily and the impact was higher as the study was applied in school setting. It is found out that school-based cognitive behavioural programme is effective on the treatment of children with high level of anxiety. Compared to the findings concerning school-based applications, it is believed that the findings of this study are consistent with the literature and that its results are similar to the programmes with high impact factors. In addition, similar results are also obtained with the effectiveness of CBT on anxiety.

It was observed that post-test scores decreased in the experiment group whereas it did not decrease in placebo and waiting list control groups, which means that there is no significant difference. de Groot et al. (2007) examined individual and group therapy with BDT-based approach in the treatment of anxiety. It is reported that there is decrease in the anxiety level of both groups and that the decrease continued in the follow-up measurements conducted three months later. Similar to the findings of de Groot et al. (2007), the follow-up measurement results obtained from the children who participated in the intervention programme three months later showed that the anxiety level of children in experiment group is significantly lower than the children in control group. According to this finding, it is displayed that the programme applied is still effective three months later.

An examination of the results of the research shows that “I can cope with my fear” programme is an effective programme which can be used in decreasing the anxiety level of 4th grade students. Accordingly, it is considered as a programme which can be applied in school psychological services. In addition, it is also found out that SCAS is a measurement tool whose reliability and validity is displayed that can be used in determination of the level and types of anxiety of children in both clinical and educative fields.