Empathy, resilence, and gratitude

The concept of empathy is studied in various fields of psychology: developmental, evolutionary, social, clinical, and recently research has developed very strongly in the field of neuropsychology (Decety & Jackson, 2004; Shamay-Tsoory, Aharon-Peretz, & Perry, 2009). Most researchers now treat empathy as a multidimensional construct, which consists of cognitive, affective and behavioral elements (Davis, 1980). Empathy is not a single disposition or ability, but a complex socio-emotional construct (Decety, 2011). The majority of scientific concepts prove the existence of two main dimensions of empathy: cognitive and affective. Cognitive empathy is the ability to adopt the perspective of the other and understand his thoughts and feelings (Reniers, Corcoran, Drake, Shryane, & Völlm, 2011). Affective empathy often entails the process of sharing similar feelings and emotions with other people (Shamay-Tsoory et al., 2009).

Resilience is defined very broadly as the ability of an individual to adapt to adversity in one’s life (Iacoviello & Charney, 2014). For example, resilient qualities may enable one to quickly recover the balance that was impaired by a traumatic event in one’s life (Ogińska-Bulik & Juczyński, 2008). Research shows that most individuals with high levels of resilience are often optimistic about life, have high life energy, are open to new experiences and curiosity, and have an internal locus of control (Tugade & Fredrickson, 2004). A similar characteristic of resilient people was put forward by Semmer (2006). People with a high degree of resilience are optimistic about the world, while difficult and stressful situations are usually treated as a challenge and a new experience. Such resilient people often hold positive thoughts about other people, and care about emotionally positive interpersonal relations.

Many studies confirm that resilience positively relates to the level of emotional intelligence, life satisfaction, positive affect, and adaptive strategies to cope with stress (Ogińska-Bulik & Juczyński, 2008). Research also shows positive associations between the experience of positive and prosocial emotions (e.g., joy, love, gratitude), and greater behavioral flexibility, a higher resilience to adversity and higher level of overall social functioning (Fredrickson & Losada, 2005). Fredrickson and Losada (2005) claim that resilience is associated with flourishing. That is, the optimal functioning of the individual, which leads to higher levels of well-being. Within situations where people have to cope with adversities, resilient individuals often experience gratitude (Fredrickson et al., 2003). In addition, studies show that gratitude may help to inhibit competitive and vengeful actions in threatening social interactions (Sasaki et al., 2020). Finally, studies show that across a broad spectrum of life experiences, during the most difficult moments of one’s life, resilient people are willing to express gratitude (Kashdan, Uswatte, & Julian, 2006).

Gratitude is a moral emotion and has also been identified as a personal strength or character virtue and is used to booster trust and emotional intimacy in relationships (Algoe, 2012, Peterson & Seligman, 2004; Tudge & Freitas, 2018). Among two sets of studies, gratitude as a permanent feature, disposition or emotion showed positive relations with empathy and trusting relationships (Algoe, Gable, & Maisel, 2010; McCullough, Emmons, & Tsang, 2002; vanOyen Witvliet et al., 2018). A high level of gratitude is related to other positive aspects of life experiences, including higher levels of happiness and life satisfaction; mental health, coping abilities, mental resistance, higher quality of interpersonal relationships, and moral and spiritual benefits in adulthood (Emmons & McCullough, 2003; Armenta, Fritz, & Lyubomirsky, 2017).

Empathy is an important factor in experiencing gratitude. People who are unable to empathize with others have difficulty seeing the efforts and help they receive from others. Gratitude requires empathy, but it also cultivates empathy and reciprocity in relationships (Algoe, 2012; Worthen & Isakson, 2007). Gratitude can also be understood as a coping response to challenging, challenging, and threatening circumstances (Sasaki et al., 2020; Worthen & Isakson, 2007), so it can be considered from the perspective of relationship with resilience. While in the literature we find studies confirming the relations between empathy and gratitude (McCullough et al., 2002), as well as between empathy and resilience (especially in the health and service professions), there is scant research on the direction and strength of the relations between resilience and gratitude.

Given that resilience is often defined as the ability to return to every-day life after stressful events and to restore emotional balance when exposed to adverse circumstances (Epstein & Krasner, 2013), feelings of gratitude may also increase feelings of competence and help one to perceive challenging events as learning experiences. Recent research (Pinho, Falcone, 2017) indicates that empathy and resilience are predictors of interpersonal forgiveness, which involves experiencing emotional, cognitive and behavioral changes of the victim towards the offender. Therefore, the present study explores the question of whether empathy and resilience can predict the level of gratitude, understood as appreciating other people and events in one’s life.

Are women more empathetic and grateful, and men more resilient?

Developmental studies with children and youth show that during childhood, emotions such as empathy are often socialized in terms of gender-role stereotypes such that parents speak more emotional terms to girls than boys (Krause, 2006). To support this claim, numerous studies on empathy show that most girls and adult females often score higher on interpersonal sensitivity and emotion recognition than males (Garaigordobil & García de Galdeano, 2006). In addition, some studies confirm that female gender empathy scores are often significantly higher than male, but only in relation to the affective but not cognitive aspect such as perspective-taking (Overgaauw et al., 2017).

In an attempt to explain such gender-related differences, many studies show that gender differences in empathy may often reflect stereotypical socially-prescribed gender-role orientations rather than one’s biological sex (Gentzler & Root, 2019; Yarnell, Neff, Davidson, & Mullarkey, 2019). That is, the social roles of women and men are based to a large extent on gender-role stereotypes about properties and traits attributed to men and women by socially are created and perpetuated through societal expectations towards men and women. For example, across many cultures, women are expected to express more moral emotions (e.g., guilt, shame), and empathy more often than men (Kashdan, Mishra, Breen, & Froh, 2009). On the other hand, however, a growing number of neuropsychological studies also confirm a female advantage in empathy at the neurophysiological level (Huetter et al., 2016).

The results of research on the relation of resilience to biological sex or age depend on the how resilience is defined as well as measured. That is, how do researchers define the resilience (as a compilation of coping and emotional skills, a character trait or personality dimension), and what research tools are used to assess individual dimensions of resilience. For example, Namy et al. (2017) distinguish different resilience dimensions: emotional support; family and school connectedness; psychological and social assets. Their research showed that self-identified gender was a moderator between resilience and other factors such as peer violence or teacher violence. In addition, Ripar, Evangelista and Paula (2008) studied the relation between gender and adolescent resilience factors and found no differences between females and males in terms of optimism or impulse control. There were, however, significant differences in the sense of self-efficacy in favor of males.

Ogińska-Bulik and Juczyński (2008) found compared to females, males often showed greater personal competencies to cope with difficulties and showed a higher tolerance for failure. Compared to females, males often perceived life more as a challenge or as a series of learning opportunities, and presented a more optimistic attitude to life combined with the ability to mobilize in challenging situations. In contrast, the Oginska-Bulik & Juczyński (2008) found no gender differences in terms of openness to experience and perseverance. The results of other studies find no gender difference in resilience and empathy, especially among physicians or medicine students (Kobayasi et al., 2018). That is, in a biomedical learning environment, males and females are more similar than different.

In gratitude, as well as empathy, females, compared with males, have been found to be more likely to experience and express gratitude (Gordon et al., 2004). Moreover, females have reported that they receive more personal gains in terms of emotional benefit from being grateful to others (Kashdan et al., 2009). For example, Kashdan et al. (2009) showed that compared to females, males were less likely to feel and express gratitude, were more likely to be critical of gratitude, and reported receiving fewer benefits. Such findings could perhaps suggest that some males may learn to believe that showing gratitude and other moral, prosocial emotions such as compassion and empathy may often be interpreted by others as evidence of emotional weaknesses and thus possibly threaten their masculinity and social position (Yarnell et al. 2019).

Given that studies also support the notion that cultural differences may also exist in gratitude expression (Tudge, Freitas, & O’Brien, 2015; Merçon-Vargas, Poelker, & Tudge, 2018), it seems reasonable to conduct research in many different countries. Such trans-cultural studies could then focus on clarifying the developmental and cultural aspects of gratitude and explore the ways in which cognitive, emotional, moral processes and values are implicated in the experience of gratitude.

The present study aims and hypotheses

The purpose of this study was to determine whether individual differences and relations exist among young adults’ empathy, resilience, and gratitude, with a focus on self-identified gender. We were specifically interested in exploring the following questions: How and why does gender influence the relations among empathy, resilience, and gratitude in adults? and Whether empathy and resilience can be predictors of gratitude?

Specifically, this study aimed to achieve the following:

Examine the differences in the level of empathy, resilience, and gratitude between self-identified males and females.

Examine the gender differences in the predictors and mediators of gratitude.

In particular, the present study tested six hypotheses:

H 1. Compared to males, females will show higher levels of empathy and gratitude.

H 2. Males will score higher in resilience levels than females.

H 3. There will be a difference between men and women in the size of the relationship between resilience and gratitude: the correlations between resilience and gratitude in men’s sample will be stronger than in women’s group.

H 4. There will be gender differences in predictors of gratitude.

H 5. Irrespective of gender, openness for a new experience will be the main mediator of the relation between empathy and gratitude.

Method

Participants

A sample of 214 (48% women) adults in early and middle adulthood, average age for total sample: M = 28.29 years, SD = 11.19; for women sample: M = 29.34 years, SD = 11.92, and for men sample: M = 27.31; SD = 10.42. The number of participants in age from 18 to 24 years old was equal to 125 (58.4%); from 25 to 40 years old was equal 50 (23.4%), and from 41 to 55 years old was equal to 39 (18.2%). All responders were recruited online within Poland. 42% of respondents came from a big city, 33% from a small town and 25% came from the village.

Once informed consent was obtained, participants completed the survey. Participants indicated their age, gender, education, and then completed the items on the scales describe below. Upon the completion of the questionnaires, anonymous responses were saved on the web server of the first author. Announcements of research were disseminated on social networks and among postgraduate students of the University, teachers in schools. Education: 34% of respondents declared higher education, 58% secondary and 8% vocational or basic education. Their professional activity was: 1. employed (42.5%), 2. student (45.5%), 3. unemployed (11%).

Measures

Empathy

The Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy (QCAE): was created by Reniers et al. (2011) and translated into Polish by Lasota & Tomaszek. The QCAE has 31 items included in five categories, two as cognitive subscales: Perspective Taking (i.e. “I can easily tell if someone else wants to enter a conversation”), Online Simulation (i.e. “Before I do something I try to consider how my friends will react to it”), and three as affective subscales of empathy: Emotional Contagion (i.e. “People I am with have a strong influence on my mood”), Proximal Responsivity (i.e. “I often get emotionally involved with my friends’ problems“) and Peripheral Responsivity (i.e. “I often get deeply involved with the feelings of a character in a film, play or novel”). Frequency are rated on a 4-point scale (1 - ‘Strongly disagree’, 4 - ‘Strongly agree’). The Cronbach’s alpha of the overall score obtained in our study .88 (omega ω = .90). The internal consistency of the five subscales have Cronbach's alpha values of between .52 and .90 (coefficient omega between .57 and .90).

Resilience

Resilience Measurement Scale SPP-25 - the authors are Ogińska-Bulik and Juczyński (2008). It is a 25-item measure of resilience in adulthood include five categories: Perseverance and determination in action (i.e. “I undertake determined efforts to achieve the goal”), Openness to new experience and sense of humor (i.e. “I am open to new experience”), Personal competencies to cope and tolerance of negative emotions (i.e. “In stressful situations, I concentrate and think clearly”), Tolerance for failures and treatment of life as challenges (i.e. “I easily adapt to new situations”), Optimistic attitude to life and the ability to mobilize in difficult situations (i.e. “The experienced difficulties motivate me to act”). The factors determined for the Polish scale show some similarity to those obtained in TheConnor-Davidson Resilience Scale (2003). The responses are given on a five-point scale (0 -definitely not, 4 - definitely yes). The overall result of resilience is the sum of five factors. Each of the dimensions contains 5 items. Internal consistency was satisfactory for five subscales scores; with alpha coefficients ranging from .56 to .90 (omega coefficient from ω = .58 to ω = .90). The total SPP25 score showed a Cronbach’s alpha of .72 (coefficient omega = .72).

Gratitude

The Gratitude, Resentment and Appreciation Test - Revised (GRAT - R) created by Thomas & Watkins (2003) in Polish adaptation (Tomaszek & Lasota, 2018). It is a tool used for measuring gratitude disposition consists of 44 questions included three categories of gratitude: Sense of Abundance (i.e. “Life has been good to me”), Appreciation for Simple Pleasures (i.e. “I really enjoy the changing seasons”) and Social Appreciation (i.e. “I'm really thankful for friends and family”). Ratings were made on a 9-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = ‘I strongly disagree’ to 9 = ‘I strongly agree’. The internal consistency reliability in our study was α = .86 (ω = .89), the average reliability coefficient for SA was α = .92 (ω = .93), AB was α = .82 (ω = .85), SAO was α = .82 (ω = .84).

Data Analyses

Several multivariate statistical procedures we conducted to test our hypothesis. Specifically, the t - student test and calculated the Cohen’s d value to exam the gender differences in the levels of analysed variables (H1,H2), and the Pearson’s Correlation were performed to test the associations between resilience, empathy and gratitude (H3). Additionally, linear multiple regression were conducted to test the most significant predictors of gratitude (H4). All above mentioned statistical analysis in the research was applied with SPSS 21 version. The SEM analysis was performed by SPSS Amos Graphics version 21 with Maximum Likelihood method, to supplemented the regression analysis and examine the mediation models (H5).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

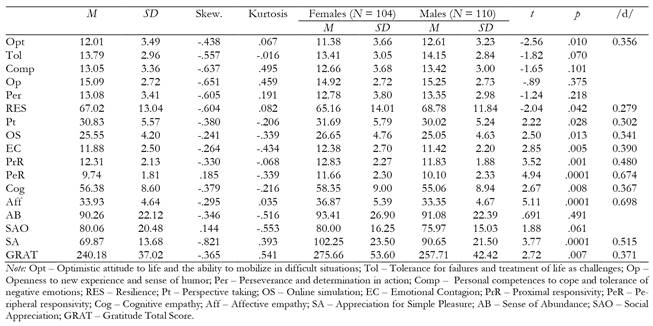

The analyses identify the differences in the level of resilience, empathy, and gratitude between male and female gender were performed by using t value statistics. Descriptive analysis showed that men scored significantly higher on resilience, but generally the results were statistically not significant among resilience dimensions. One significant difference was found that showed males were more optimistic than women. The effect sizes measured by Cohen’s d was small in both cases. Table 1 reveals support for Hypothesis 1. Females scored significantly higher on the QCAE scale. The size effects for cognitive empathy and its dimensions and for affective dimensions such as Proximal responsivity and Emotional Contagion were small (d = 0.30 - 0.37), and for affective empathy and its Peripheral responsivity dimension were average. The t student value revealed statistically significant gender differences in gratitude total level and its dimension Appreciation for Simple Pleasure. Women got higher scores in both gratitude measures. The size effect for GRAT was small and for Appreciation for Simple Pleasure was average (see Tab. 1).

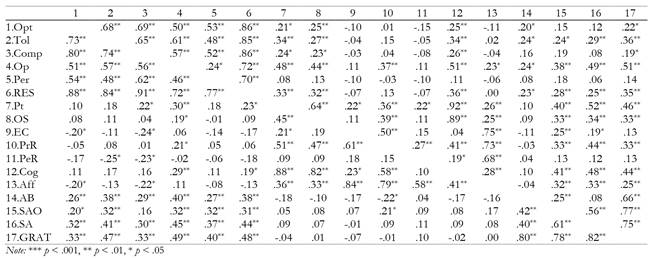

Pearson’s Correlation Analysis

In women’s sample higher gratitude was connected with higher resilience, and only one dimension of affective empathy (Proximal Responsivity). In men’s sample gratitude correlated with higher levels of resilience (along with its all dimensions) and empathy (except Peripheral Responsivity). What is more the relation between gratitude and empathy was generally stronger for males (see Tab. 2).

Predictors of gratitude for male and female sample - multiple regression analysis

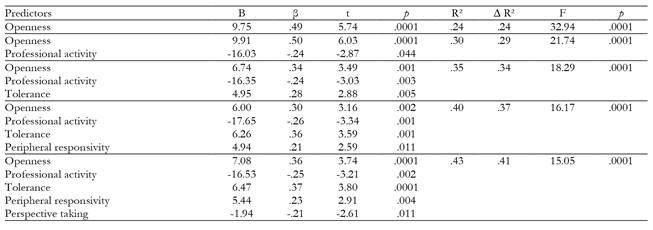

In all tested regression models the dependent variable (VD) was gratitude total score (GRAT), and the independent variables (VI) were indicators of empathy and resilience and sociodemographic characteristics.

In the first regression model we tested the extent to which resilience, affective and cognitive empathy and sociodemographic characteristics: age, place of residence, education, professional activity influenced the total gratitude level. In women’s sample two significant predictors emerged: resilience (ß = .46, t = 5.49, p = .0001) and professional activity (ß = -.18, t = -2.04, p = .044). Adjusted coefficient of determination ΔR² = .24, statistics for model F = 17.63, p < .0001. In men’s sample we found main effects for levels of cognitive empathy (ß = .36, t = 4.00, p = .0001) and resilience (ß = .22, t = 2.37, p = .020). Parameters of the model ΔR² = .22, statistics for model F = 16.35, p < .0001.

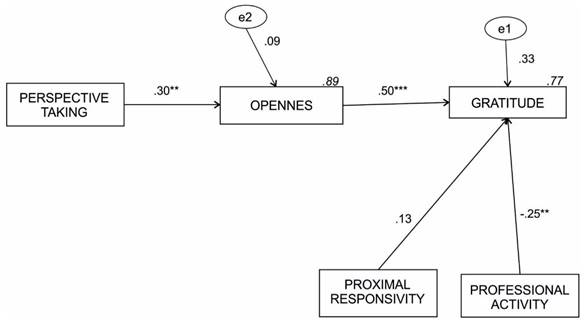

Next we conducted the second regression analysis concerning resilience dimensions, empathy dimensions and sociodemographic characteristics. Five explanatory variables had significant impact on the level of gratitude in the women’s group: Openness for a new experience and sense of humor (ß = .36, t = 3.74, p = .0001), Tolerance (ß = .38, t = 3.80, p = .0001), Proximal responsivity (ß = .23, t = 2.91, p = .004), Perspective taking (ß = -.21, t = -2.61, p = .011) and Professional activity (ß = -.25, t = -3.21, p = .002). Those variables explained 41% of the variances in gratitude total score (∆R² = .41 (see Tab.3).

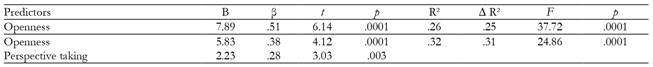

As seen in Table 4, in the group of men in equation regression Openness for a new experience was the strongest significant predictor of the gratitude (ß = .38, t = 4.12, p = .0001). The second significant predictor found in men’s sample was Perspective taking (ß = .28, t = 3.03, p = .003). The model explained 31% of the variances in gratitude score.

Models of resilience, empathy and gratitude relationships for males and females

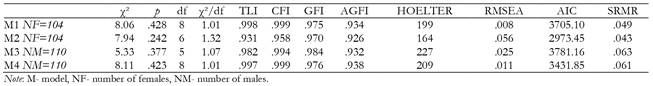

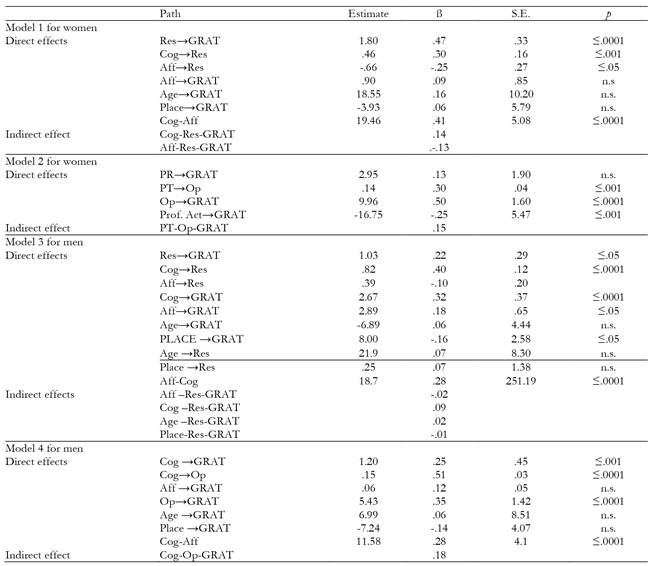

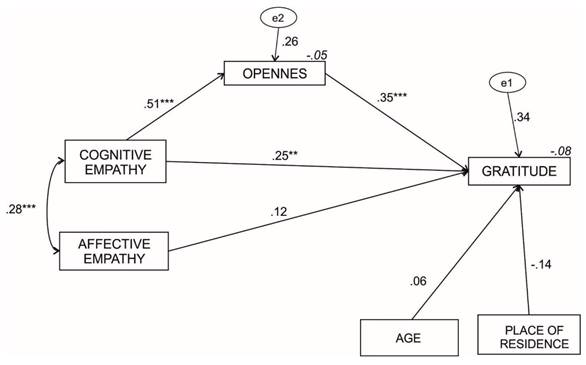

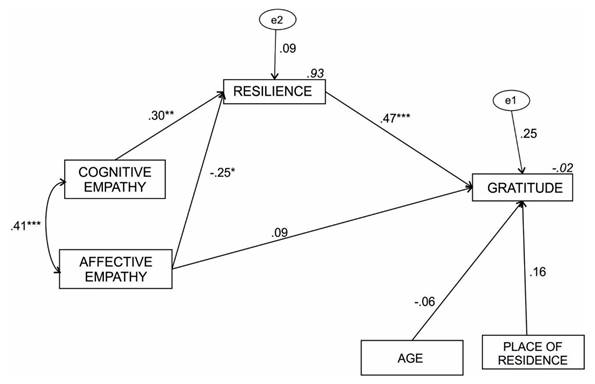

In all models the first endogenous variable was gratitude total score, and the second endogenous variables were resilience total score (models 1 and 3) and its dimension openness for a new experiences (model 2 and 4); the exogenous variables were cognitive and affective empathy, place of residence and age (model 1, 3, 4), and dimensions of empathy: proximal responsivity and perspective taking and professional activity (model 2).The tests of multivariate normality of endogenous variables in all models indicated a normal distribution. Model 1 and 2 examined the relationships between tested variables in female group, model 3 and 4 in male group. Fit indexes for all models are in the Table 5.

In Model 1 (see Table 6 and Figure 1), the strongest positive direct impact had Resilience (.47). The total effects of Cognitive empathy and Resilience on Gratitude was .14. The indirect effect of Cognitive empathy through Resilience was also 14. In model affective empathy indirectly impacted on the gratitude level (-.12). Model explained 25 % of the variances in Gratitude and 9% of the variances in Resilience.

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Figure 1. Structural Model Examined the Relationship Between Empathy, Resilience and Gratitude in Women’s Sample.

Model 2, presented in Table 6 and Figure 2, tested only indirect effect Perspective taking through Openness on Gratitude. Openness for a new experience was the most important positive predictor of Gratitude (the direct impact was =.50). Professional activity (-.25) was also a significant factor affecting Gratitude (ß =-.25), (employees had a higher level of gratitude than students). Standardized Indirect Effect of Perspective taking on Gratitude was.15. Estimates of squared multiple correlations output for Openness was .09 and for Gratitude was .33.

Note. **p < .01, ***p < .001

Figure 2. Empathy and Resilience Dimensions, and Gratitude Level - Structural Equation Model for Females.

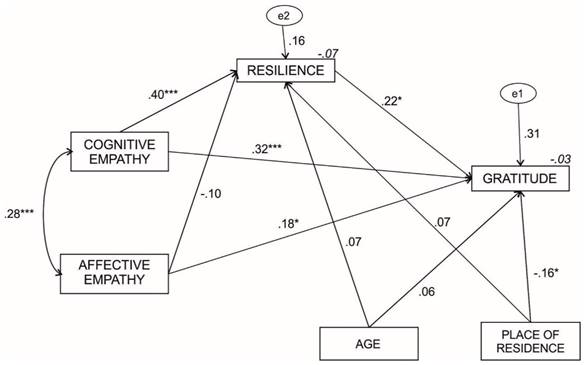

In Model 3 the positive significant direct impact had Resilience (.22), Cognitive empathy (.32), Affective empathy (.18) and Place of Residence (-.16). The indirect effects on Gratitude through Resilience were observed for Cognitive empathy (.09), Affective empathy (-.02), Age (.02) and Place of Residence (-.01). Cognitive empathy also significantly directly affected Resilience (.40). Estimates of squared multiple correlations output for Resilience .16 and for Gratitude was .31 (see Tab. 6 and Figure 3).

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Figure 3. Structural Model Examined the Relationship Between Empathy, Resilience and Gratitude in Men’s Sample.

In the last model (Figure 4), the level of gratitude was affected by openness for a new experience (.35) and cognitive empathy (.25). The total effect of Cognitive empathy and Openness on GRAT was.43. The indirect effect of Cognitive empathy through Openness was .18. The level of Cognitive empathy significantly directly impacted the level of Openness (.51). Estimates of squared multiple correlations output for Openness .26 and for Gratitude was .34.

Discussion

Overall, results confirmed our hypothesis that emerging adult females scored higher than males in empathy and gratitude. These results confirm previous findings related to gender differences in the experience of positive emotions such as empathy or gratitude in adulthood (Kashdan et al., 2009), as well as in more recent studies (vanOyen Witvliet et al., 2018).

How can we explain the finding that females scored higher on empathy and gratitude among males in early adulthood? As mentioned earlier, one possible explanation could be based on the notion that interpersonal perceptions focus on emotional warmth and cognitive competence, as both aspects of a person’s character may influence one’s judgement and social behavior (Fiske, Cuddy, & Glick, 2007). Given societal gender-role expectations (Rogers et al., 2019), an emotionally warm orientation, defined as other-focused and motivated to improve interpersonal relations, is more often attributed to girls and adult females. Competence orientation and motivation, that is, a self-focus on one's own goals, is more often identified with the social male gender (Fiske et al., 2007). Consequently, in self-report studies, most females in accordance with stereotypic gender-role expectations show greater readiness to present empathic behavior. In contrast, to protect themselves from any associated negative emotions or social consequences, males might avoid experiencing and expressing empathy or gratitude (Froh, Yurkewicz, & Kashdan, 2009).

The present results show that compared to females, males scored higher level of resilience, but only in one dimension - Optimistic attitude toward life and the ability to cope in difficult situations. Openness to new life experiences and sense of humor emerged as a common the strongest predictor for gratitude in the male and female group. But for females only, higher levels of resilience and empathy dimensions predicted higher levels of gratitude. Openness to new experiences, Tolerance for failures and treatment of life as challenges, Peripheral Responsibility, and Perspective-taking were also found to be significant predictors of the gratitude in women but not in men.

Moreover, results revealed relations between gratitude and perspective-taking (Pt). Among males we found higher levels of Pt were related to higher levels of gratitude, but among females, higher Pt levels were related to lower levels of gratitude. The significant predictor of gratitude among females was also their professional activity. The SEM results indicated that among females, empathy indirectly influenced gratitude via resilience. Among males, there were direct and indirect influences of empathy on gratitude. Such findings support past studies that suggest that a person’s biological sex may have an indirect influence on gratitude through empathy (vanOyen Witvliet et al., 2018). This could be due to the reason that gratitude includes prosocial interactions such as reciprocity, and the experience of positive emotions (self and other), including empathy. However, empathy may not necessarily invoke feelings of gratitude (vanOyen Witvliet et al., 2018).

Our research suggests that the relations between dimensions of resilience and gratitude are gender-differentiated. Compared to males, in females two dimensions of resilience: open-mindedness or the ability to remain mentally open to new situations, and a sense of humor, and tolerance for failures were predictors of gratitude. Thus, females who learn how to cope with difficult everyday experiences also reported higher levels of gratitude but not empathy. In contrast, among males, the ability to perspective-take (Pt), and remain open to new experiences significantly predicted gratitude. Thus, for both genders, Pt and openness may have a positive impact on the assessment of stressful situations in everyday life, and on the selection of more effective and adaptable coping strategies (Ogińska-Bulik & Juczyński 2008; Fredrickson & Losada, 2005).

The present results indicate that empathy combined with resilience (especially openness to new experiences) may help one to feel gratitude. Perhaps because empathy may empower people to view interpersonal relationships as learning opportunities to develop one’s character, and resilience allows them to enrich their experiences and see things from many perspectives. From the cognitive model of resilience, it is the ability to flexibly apply appropriate cognitive processing that is relevant to the current situation (Parsons, Kruijt, & Fox, 2016). Moreover, the ability to remain mentally and emotionally flexible in life enables people to interpret difficult situations as challenges and learning opportunities as opposed to roadblocks and threats (Sasaki et al., 2020). In cognitive model of resilience partially it supports individual variations in how people interpret and appraise different situations, also in the social context. Therefore, it is enhancing one’s understanding of other motives and purposes.

Further, grateful people are also often more likely to focus on the positive aspects of life, and thus more likely to experience positive emotions such as exhilaration and joy, (Watkins et al., 2018). Perhaps that is why some studies show that most adults who have a higher sense of humor are more open to life experiences and report higher levels of resilience and gratitude (Cann & Collette, 2014). Our research results confirm the thesis that people in adulthood who discover new objects and perceive the world from multiple perspectives are also more likely to flourish and experience higher life satisfaction (Fredrickson & Losada, 2005). Thus, our findings suggest that perhaps the most grateful people in life are those who are open to and enjoy novel life experiences.

This research also suggests that encouraging people to be open to new experiences can contribute to a more developed sense of gratitude to the world and others. For example, teachers and leaders may serve as role models and promote the use of open-mindedness and accepting attitudes towards diversity through dialogue and inquiry in the classroom to promote critical and reflective thinking skills (Ramsey & Gentzler, 2015).

Limitations and Future Directions

Nonetheless, despite the contributions of the present study to the literature on resilience and emotional experiences in young adults, many questions remain that may encourage future studies. First, it would be useful to measure psychological resilience using other methods, beyond self-reports such as neurophysiological measures (e.g. fMRI). Second, given the multidimensionality and complexity of the empathic process, methodological challenges continue to exist such as how to measure empathy and its dimensions. Most studies use self-report questionnaires to examine dispositional empathy, and more often, neuronal research that measures situational empathy fails to provide an unequivocal answer about the existence of gender differences.

Thus, to capture the complexity of empathic sensitivity, future studies should combine self-report and neurophysiological measures. Third, given that the present study focused on self-report measures, general language and cognitive abilities such as working memory may also have influenced the results and such measures should be included in future studies. Finally, although this study focused on the differences between self-identified females and males, gender-role orientation, or the extent to which individual relate to gender-role stereotypes about femininity (e.g., females more empathic) and masculinity (e.g., males more agentic) may have played a role in the present study and should be explored in future studies.

Conclusion

Overall, results indicate that self-identified gender plays an important role in the relations among emerging adults’ empathy, resilience, and gratitude. Accordingly, this study provides novel information regarding the complex diversity among the social and moral experiences of females and males and suggests a nuanced understanding of gender differences in young adults’ experiences of gratitude, empathy, and resilience is needed.