Introduction

Depressive disorders are a secuence of chronic and disabling alterations with an early onset, where processes associated with autonomous thinking (e.g., life values and principles), life beliefs (e.g., gender identity), social interactions (e.g., family, friends and romantic relationships) are altered under negative symptomatology, being one of the most prevalent mental disorders throughout life (De Oliver et al., 2018).

According to different studies, adolescents are one of the high-risk groups for the development of depressive disorders, with estimates ranging from 8% to 20% before the age of 18 years. (De Oliver et al., 2018; Kendall et al., 1989; Naicker et al., 2013). Moreover, suffering from depression in adolescence increases the risk of depression in adulthood. Specifically, it is estimated that adolescents with depression were 2.78 times more likely to have depression in adulthood (Johnson et al., 2018) having a long-term impact on physical and psychological health as it is a predisposing factor for chronic diseases and decreases functional condition (Aguilar-Navarro & Ávila-Funesa, 2007; King et al., 2018). It also tends to present comorbidly with anxiety (Camuñas et al., 2019), substance use (Restrepo, et al., 2018), or suicide risk (Buitrago & Parra, 2018).

During adolescence, new norms are assumed and experienced in different contexts (e.g, behaving differently in front of different groups of friends or social situations), to which the adolescent is in a constant adaptation process. They develop coping strategies that allow them to effectively manage these and other situations (within a normalized functionality), while giving meaning to a coherence between what they do in different settings and their own identity, character, values and goals (Fontaine et al., 2019; Morales & Trianes, 2010; Pineda & Aliño, 2002; Thapar et al., 2012). These processes involve psychosocial instability periods where the adolescent is highly exposed to new stressors under a process of transition from adolescence to adulthood and living in risk situations (e.g., alcohol, prohibited substances, intimate relationships) or family conflicts (e.g., questioning established family rules and roles).

Such combination of elements (e.g., search for identity, management of new situations, experimentation with limits, development of personal tools and self-regulatory resources, search for referents), entails a high emotional demand and as a consequence, a greater emotional reactivity in the adolescent. That will represent a threat to the emotional health of youth, when combined with the many new challenges and stressors that accompany this period (Montes et al., 2018).

Although the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders and Diseases (DSM-V) understands that depression is the result of the concurrent and continuous presence of specific symptoms over a minimum period of time (APA, 2006), Folkman (1997; 2008), defends that it is necessary to take into consideration not only the symptoms and duration that are present, but also the emotions and coping styles of the stressful situations in order to understand depression more effectively. According to Moscoso (2014a; 2014b), the comprehension of depression as a disorder has been advancing and evolving.

The development of theoretical frameworks for this model (Folkman 1997; 2008; Moscoso et al., 2012) has made it possible to move away from approaches that focus exclusively on the presence and intensity of associated symptoms, and to replace them with dynamic approaches that provide a broader understanding of the presence, development and functionality-dysfunction of the disorder, as well as its symptomatic expression, based on the experience of emotions and coping styles in critical or stressful situations (Moscoso, 2014b).

Moscoso (2014a), describes depressive disorders as "a dysfunctional picture that occurs within a process of coping with the stresses of daily life". This approach is based on the premise of stress as a risk factor for the appearance of depressive disorders, which has been widely justified in the scientific literature (Beiter, et al., 2015; De Kloet, et al., 2016; Iqbal et al., 2015) and indicates that this dysfunctional association occurs, especially, in people who experience a high negative emotion (Mayberg, 2004).

Secondly, this approach assumes that vulnerability to stress and its ultimate expression in the form of depressive disorders or episodes is supported by the personality and its characteristics (functional/dysfunctional), which will modulate the experience of stress to which the person is exposed, and his or her emotional and physiological response and therefore, will configure individual differences in the development of the disorder (Antolína et al., 2008; Conrad, et al., 2009; Vangberg et al., 2012).

The concepts of eustress and distress are central to the Moscoso Depression Model (2014a, b). In it, the responses of eustress are considered as positive coping styles in which an adequate identification of one's own emotions is made, offering a better psychological health (Bahamón et al., 2019), thus promoting the quality of life (Karimi et al., 2016). On the other hand, there coexist (without being opposed) responses of distress, focused on psychological distress and understood as passive coping styles, characterized by the perception and expression of negative emotions and states, favored by the loss of control in certain situations (Kuhn et al., 2018; Yap et al., 2007) and the decrease of the quality of life events (Bahamón et al., 2019; Horwitz et al., 2018).

The fact that eustress and distress are coexisting concepts and not mutually excluding, explains how an adolescent exposed to high levels of stress or with risk contexts for the development of depressive episodes (e.g., a sentimental break-up in adolescence, school failure) does not finally develop the disorder. Under this paradigm, experiencing negative emotions (related to the appearance of the disorder) is compatible with the capacity to feel positive emotions using cognitive re-evaluation strategies (e.g., positive view of different situations) or goal-oriented coping (e.g., enthusiasm for the future) and to experience daily events with a positive meaning (e.g., feeling happy with daily activities) (González-Hernández & Ato-Gil, 2018; Folkman, 2008).

Authors as Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi (2000) or Zautra and Smith, (2001), support the vision of Folkman and affirm that positive emotions, allow to the subject greater psychological and physiological adaptation, providing benefits for the health with significant effects in processes of disease (Louro et al., 2018), trauma (Echeburúa, & Amor, 2019) or mourning (Magaña et al., 2019) among others.

Furthermore, from the perspective of the distress-eustress, temperamental reactivity and emotion-regulating strategies have been identified as precursors for the development of depressive symptoms in youth (Yap et al., 2007). In this sense, the theoretical approach developed by Cloninger, which explains and understands the differences of individuals on the development of temperament and character, defining personality as "the internal causes underlying the individual's behavior and experience" (Cloninger, 2003, p.3)

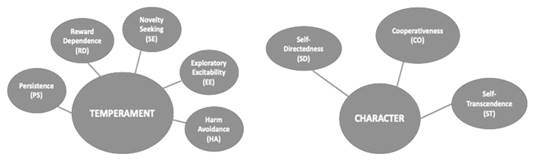

Cloninger (2003), in his Psychobiological Model, explains personality through the fusion of the biological bases of traits and experiences lived in the s socio-cultural interaction process between Temperament (understood as the most innate tendencies, based on the first teachings and impressions developed in the child) and Character (process of mental construction and maturation, where the person builds his personal and social identity).

This model considers temperament as a more or less stable emotional response tendency (more biological) (see figure 1), expressed through automatic emotional and behavioral responses to environmental stimuli (Nilsson et al., 2019; Qiu et al., 2017), that it has some stability from childhood to adulthood (Amad et al., 2013; Escribano, et al., 2016; Oltmanns & Balsis, 2011; Sigvardsson et al., 1987) and does not differentiate among cultures (Brändström et al., 2001; Yamagata et al, 2006). Affective models of depression have suggested that individual differences in temperamental reactivity, a key component of temperament, may predispose individuals to develop depressive disorders (Hyde et al., 2008).

On the other hand, character is considered as the intentional behaviors that the individual executes, but that are also strongly influenced by the perception that the person has of himself (self-concept). Temperament and character can be analyzed and comprehended on the base of a two-dimensional structure (Cloninger, 2003) with a common characteristic that relates them to the capacity of activation, inhibition and maintenance of behavior in a specific situation.

Previous research with Cloninger's psychobiological personality model shows that the risk of depression is associated with high harm avoidance, low novelty seeking, self-directedness and persistence (Cloninger et al., 2010; Cloninger et al., 2012; Farmer et al., 2003). In contrast, cognitive-emotional readjustments are associated with low scores in harm avoidance and high scores in self-directedness, cooperation and persistence (Martinez-Torteya et al., 2009). One brain image study showed that these personality traits can be linked to a specific brain circuitry that modulates mood and reward-seeking behavior (Cloninger et al., 2012; Gusnard et al., 2003). Dysfunctional attitudes that increase the risk of depression are largely explained by low self-direction, as expected from the cognitive theory of depression, while others influence particular circumstances (Richter & Eisemann, 2002; Sheynikhovich et al., 2013).

The aim of this study was to explore the differences existing under different personality profiles (Cloninger, 2003) among elements described in the depressive process (absence of distress and the presence of eustress) (Moscoso Model, 2014) in a sample of adolescents. The hypotheses proposed were: a) exists at least one profile in which there is a risk for the manifestation of the depressive response, mainly due to high levels of reward dependence and/or novelty seeking, and low levels of self-directedness, accompanied by the appearance of distress; and b) exists a profile in which it is possible to indicate protection factors for the appearance of the resilient response, due to low indicators of reward dependence, exploratory excitability and harm avoidance, and high indicators of self-directedness and self-transcendence accompanied by the appearance of eustress.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedure

The total sample consisted of 229 participants, 121 men (52.83%) and 108 women (47.16%) aged 12 to 20, with a mean age of 14.79 (SD = 1.61). Participants were enrolled in different public scholar centers in the south of Spain, of which 41 (19.9%) belonged to the first year, 31 (13.53%) to the second year, 66 (28.82%) to the third year, 47 (20.52%) to the fourth year and 44 participants (24.2%) are enrolled in high school. Once the tutors of each center were informed, an informative document was sent to parents or legal guardians on the usefulness and ethical rigor of the research, also requesting consent for the participation of the minors.

The administration measures was a group, in pencil and paper, and always with the presence of a member of the research team in order to attend to any incident. The participants were informed of the voluntary nature and absolute confidentiality of the responses, complying with the ethical requirements of the Declaration of Helsinki (2017).

Measures

Sociodemographic. An "ad hoc" sociodemographic data record was created, including closed-ended questions on age, course, gender (see Table 1).

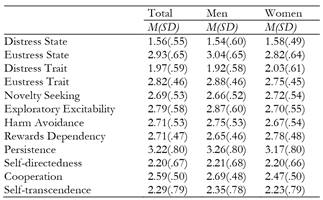

Depression. The Multicultural Depression Inventory, State-Trait (IMUDER; Moscoso et al., 2012) was used to evaluate the indicator of depression. It allows to know the depressive states and traits in non-clinical populations by exploring the person's positive-negative emotions, cognitions and coping. This instrument of 24 items grouped into 2 first-order factors (State Depression - Trait Depression) and 4 second-order sub-factors (State Distress, Trait Distress, State Eustress, and Trait Eustress) is answered using a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 ("not at all" for state depression items; "almost never" for trait depression) to 4 ("very much" for state depression; "almost always" for trait depression). This instrument has been used in the adolescent population and used to address similar objectives while adequately maintaining the factor structure (González-Hernández, & Ato-Gil, 2019). In this work, the scale presented an adequate factorial structure and an internal consistency of between α =.78 and α =.85 (see Table 2).

Personality and Temperament. Short version of the Temperament and Character Questionnaire was used (TCI-R-67, Pérez, 2009). The self-report inventory consist of 62 items grouped into 8 factors corresponding to the dimensions of Cloninger's model (2003). Four of the seven dimensions correspond to temperament (1 - Novelty Seeking (e.g. I often do things based on how I feel at the time without thinking about how they have been done in the past); 2 - Harm Avoidance (e.g. I often feel tense and worried in unfamiliar situations, even when others think there is no danger); 3 - Reward Dependence (e.g. I like to talk openly with my friends about my experiences and feelings instead of keeping them to myself); 4 - Persistence (e.g., I like challenges more than easy ones); and 5 - Exploratory Excitability (e.g., I like to explore new ways of doing things)), and the remaining three correspond to character (6 - Self-directedness (e.g., I often think my life has little meaning or purpose), 7 - Cooperation (e.g., I have no patience with people who do not accept my views), and 8 - Self-transcendence (e.g., I have sometimes felt that I am part of something that has no limits or boundaries in space or time)). A 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). It has been validated in the general Spanish population (Gutiérrez-Zotes, et al., 2004) and its psychometric properties have been studied in large samples of students (Garabito, et al., 2002). In the present work the scale presented an adequate factorial structure and an internal consistency of between α =.85 and α =.69 (see Table 2).

Data analyses plan

SPSS version 25 has been used for statistical processing. The data processing in this work has been carried out at different levels: As an initial procedure, descriptive analyses of the sample were performed, including central tendency analysis, normality on the socio-demographic data, frequency and estimation of the internal consistency of the measures by means of Cronbach's Alpha coefficient. After checking the fit of the scales and the normal distribution, the use of parametric tests was deemed appropriate, correlation analyses of the variables were carried out to check the links of the variables under study, and exploratory analyses of the configuration of clusters (cluster analysis) and differentials on the resulting profiles (ANOVA).

Results

Descriptives and Correlations

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the elements taken into account within this study. As can be observed, means in distress range from M = 1.56 for state and M = 1.97 for trait distress, while in the experience of positive emotions or eustress the means range from M = 2.93 for trait and M = 2.83 for eustress trait. With respect to temperament, highest scores are observed in the traits of persistence (M = 3.22) and exploratory excitability (M = 2.79), and the lowest scores are observed in the scales of self-direction (M = 2.20) and self-transcendence (M = 2.29).

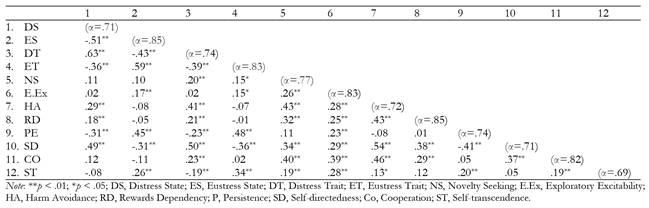

Table 2 shows the correlation analyses of the main study variables. Adolescents who feel moved to seek sensations, point out in a low, direct and positive way both with the experience of distress state as with eustress state. On the other hand, those present higher excitability develop (although with a low weight in the relationship) experiences of positive emotions in the form of state and trait eustress. Meanwhile, adolescents who develop greater responses of avoidance of adverse stimuli (avoidance of harm) present (with low correlation index) greater elements of state distress and with a moderate strength of the correlation with the trait distress. The same applies to reward dependence, which has a direct, low and positive relationship with state and trait distress.

In terms of persistence, adolescents who are better able to maintain effort behaviors express (with a moderate correlation weight) higher levels of both state and trait eustress, as well as lower levels of both state and trait distress. The opposite occurs with those adolescents who show a clear orientation towards their life goals (self-direction) and respond with maturity in the process of achieving goals, they present moderate and inverse relationships with both state and trait eustress indicators, and totally the opposite with both state and trait eustress indicators. Finally, it should be noted that those adolescents who project their actions and moments towards a future orientation and responsibility (self-transgression), present (with low and moderate strength) higher scores of state and trait eustress, as well as lower indicators of trait distress.

Cluster analysis

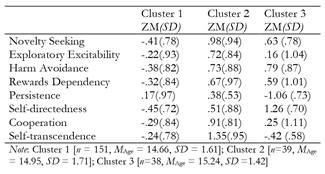

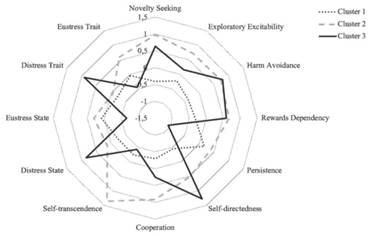

Cluster analysis was used (see table 3) to establish similarity groups in relation to the different temperamental and character variables (adolescent profiles). Specifically, a cluster analysis was used with the K-Media method from the z-scores of the variables. Different solutions were proposed with two, three and four clusters, opting for the solution of three clusters since it was the one with the best master distribution according to the average values of the elements of temperament and character for each of the clusters obtained.

Cluster 1 (n=151), presented similar scores in all indicators, thus creating a homogeneous profile among the personality indicators. While cluster 2 (n=39) presented higher scores in the indicators of temperament and character, standing out above the rest of the cluster especially in the indicators of Novelty Seeking, Persistence, Cooperation, Harm Avoidance and Rewards Dependency. Cluster 3 (n=38) presented a different and less homogeneous pattern where low persistence and self-transcendence, with high Self-directedness, Harm Avoidance and Rewards Dependency stood out.

Figure 2 shows the identified profiles, as well as the average scores for eustress and distress indicators obtained for each profile. As can be appreciated, Cluster 3 presents higher distress scores (negative emotion) with respect to the other two cluster, and lower eustress scores (positive emotion) with respect to adolescents classified as cluster 1 or cluster 2.

Significant differences were found in distress scores with adolescents in Cluster 3 having higher Distress State indicators (F (224,4) = 21.73, p < .01) than adolescents in Cluster 1 (I-J = 1.08, p < .01) and Cluster 2 (I-J = .72, p < .01). As well as greater indicators of Distress Trait (F (224,4) = 23.00; p < .01) with respect to adolescents in cluster 1 (I-J = 1.12, p < .01) and cluster 2 (I-J = .96, p < .01). In addition, they present significantly lower scores in the indicators of Eustress State (F (224,4) = 11.59; p < .01) with respect to adolescents in cluster 1 (I-J = -.74, p <. 01) and cluster 2 (I-J = -.96, p < .01); and lower scores in Eustress trait (F (224,4) = 12.31; p < .01) with respect to adolescents in cluster 1 (I-J = -.70, p < .01) and cluster 2 (I-J = -1.05, p < .01).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore the associations between personality and depressive response in adolescents. To do so, innovative theoretical approaches in two areas extensively developed in the scientific community, depression and personality, have been taken into consideration. The hypotheses raised sought to confirm differential profiles on personality and depression characteristics in a sample of Spanish adolescents, searching to find at least one risk profile and one protective profile of the depressive response.

The results obtained have allowed us to accept the working hypothesis 1 where we have found the existence of a risk profile for the appearance of depression that includes high indicators of novelty seeking, harm avoidance and reward dependence together with a reduced self-transcendence. These results are in the line with what is indicated in the literature where it is pointed out that people with a best adjustment are those who are not focused on avoiding the error or need external reinforcement to assess themselves since they have clear objectives and are highly committed to them (Antolína et al., 2008; Cloninger et al., 2010; Cloninger et al., 2012; Gusnard et al., 2003; Martinez-Torteya et al., 2009).

In addition, it has been possible to confirm hypothesis 2, where adolescents who present low indicators of reward dependence, exploratory excitability or avoidance of harm, and high indicators of self-directionality and self-transcendence, present higher indicators of eustrus than of distress and therefore have a lower risk of depression (Antolína et al., 2008; Cloninger et al., 2010; Cloninger et al., 2012; Karimi et al., 2016; Farmer et al., 2003).

On the other hand, it has been possible to verify that, as far as risk profiles are concerned, there are more nuances where the role played by the elements of persistence, cooperation and self-reliance are crucial. The fact that there are two profiles (Cluster 2 and Cluster 3) where the elements that were expected to be risky when they occur in high scores (search for novelty, dependence on reward and avoidance of harm) but which present different patterns of distress-stress is very interesting. It leads one to think that the capacity to make an effort, tolerating frustration, having clear goals, committing to them and being able to empathize or cooperate with peers, allows adolescents to buffer experiences of distress and experience more eustress, even though dependence on external reinforcements, or fear of error, are elements that remain high. These data extend and add to the findings of the literature that the risk of depressive disorders is related to high harm avoidance, low self-direction and low persistence (Cloninger et al., 2012; Cloninger et al., 2010; Farmer et al., 2003).

In this line, Cloninger and cols. (2012) in their study about the role of persistence in mood disorders that this trait has a fundamental role in the experience of negative and positive emotions in the same person, becoming a protective element of depression in those people who feel happy, energetic, active, etc. While it is an element of risk in people who feel annoyed, nervous, guilty, etc., point out that the positive or negative sign that acquires persistence depends largely on the elements that accompany it. People with a high degree of persistence tend to be highly perfectionist people who experience both positive and negative emotions with high intensity, unless they simultaneously present low damage avoidance (i.e., calm and high tolerance to frustration) and low self-direction (i.e., aimlessness).

The evidence presented in this paper, while pointing out that when there is high persistence along with other risk elements (e.g., avoidance of harm or dependence on reward) adolescents apparently experience more distress than those with high persistence but low dependence on reward and avoidance of harm, has not allowed us to find significant differences between the experiences of distress. Despite that, the role of persistence in the protection of depression is confirmed, since, in addition to presenting inverse relations with the distress and direct with the eustress, in those young people with low persistence, the experiences of positive and negative emotions were significantly smaller and greater respectively, with respect to the companions who presented higher levels of persistence.

Furthermore, as Cloninger et al., (2012) point out the role of harm avoidance and self-direction, the results obtained add information to the functioning that these variables have in depression. Specifically, the results found indicate that the combination of high harm avoidance, high dependence on reward, low persistence, high self-management and low self-transcendence are a high-risk combination for experiencing negative emotions and the absence of positive emotions, and therefore depression. Whereas, when there is high avoidance of harm and high dependence on reward in adolescents, but high persistence and self-transcendence, the impact on experiencing positive emotions rather than negative emotions is positive.

In other words, there is a high risk of depression when an adolescent, despite being clear about his or her goals (self-direction) is not persistent, and his or her assessment of situations depends on the rewards he or she perceives from the context and is afraid of suffering (risk profile). In the case of a high degree of persistence, the indicators of depression are reversed and allow the adolescent to experience more positive emotions than negative ones (protective profile).

These results must be interpreted in light of the study's limitations. Firstly, the measurement of variables by means of self-report questionnaires may create a shared variation of the method and is subject to self-presentation requirements. Therefore, future research using multiple methods (e.g., multiple reporters, behavioral tasks) is needed to reduce source bias. Second, the study design was cross-sectional, which does not allow for robust inferences to be made about causality and the direction of effects. Therefore, more rigorous study designs (e.g., experimental, prospective longitudinal) are needed to allow stronger inferences about causality.

Conclusion

The relevance of the present findings resides in the fact that they highlight the explanatory role that personality has in the development of the functionality vs. dysfunctionality of depressive disorder, and the importance of evaluating jointly the different elements of personality to determine preventively the level of risk to present a depressive disorder, in order to put into action mental health promotion factors that could be consolidated throughout childhood and adolescence. Furthermore, this research has allowed evidence not only of the elements of risk, it has also opened a door for the design of mental health prevention strategies in adolescents and has pointed out the direction for the design of strategies personalized for each one of them that are more effective and allow them, through the development of their individual characteristics, to reverse the level of risk for this type of mental illness.

From the clinical point of view, this study will allow professionals to be more effective in their treatments since they will be able to adjust the priorities of the intervention with greater precision, taking into account the personality profile of the adolescent and his or her needs to confront different situations and thus, together with the rest of the elements of the therapy, obtain a better adaptation to the context in the shortest possible time.