Introduction

The study of happiness and well-being is receiving increased attention in different fields, for example in psychology, among others. These works address issues such as the definition of these two concepts, the different ways there are to experience these states, and the evaluation of said constructs (see Diener & Oishi, 2004, 2006; Diener et al., 1998; Lyubomirsky, 2008; Peterson, Park & Seligman, 2005; Peterson et al., 2007). Another important line of research it’s focused on the concrete benefits of happiness, in this sense, some of the topics studied are its relationship with depression (Lomas et al., 2018), access to higher education (Nikolaev, 2018), transsexuality (Prunas et al., 2017), cross-cultural (Wang & Wong, 2014), societal welfare (Diego-Rosell et al., 2018), leisure (Newman et al., 2014), personality (Anglim & Grant, 2016; Morán et al., 2017) among others.

Recent research into well-being has focused on delving deeper into the individual’s conception about the experience of well-being (McMahan & Estes, 2011a). As previously mentioned, one of the aspects that has received attention is the development of instruments that make it possible to evaluate well-being. In this regard, McMahan and Estes (2011a) created the Beliefs about Well-Being Scale (BWBS) to assess the meaning that well-being has for people. The main contribution of this study is the adaptation of this scale to the Spanish population, as no similar instrument exists in our context.

One of the main lines of research in the study of happiness focuses on addressing the mechanisms that make it possible to increase levels of happiness (Bryce & Haworth, 2002; Lyubomirsky, 2008; Seligman, 2002; Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2006; Tkach & Lyubomirsky, 2006). In this regard, Lyubomirsky, Sheldon and Schkade (2005) referred to happiness as a feeling of subjective well-being characterized by a large number of positive feelings, a low number of negative feelings and elevated levels of satisfaction with life. These authors developed a theoretical model in which they assert that a person’s habitual level of happiness is mainly defined by three factors: reference value, circumstances and deliberate activities. Reference value refers to genetically determined aspects that are therefore fixed, stable over time and immune to influence or control. The second component, circumstances, refers to stable factors (civil status, work, income, health, etc.) and temporary factors (increase in income, illness, receiving an award, etc.) which do not have a permanent influence over time. Lastly, according to the model, deliberate activities refer to the wide variety of activities from which an individual has the power to choose freely, and each of which carries implications of its own. These activities require one to exert a degree of effort; in other words, one must intend to carry them out, they do not simply befall the individual. It is precisely these deliberate activities that allow for a solid and stable increase in people’s levels of happiness and that affirm what Lyubomirsky et al. (2005) posited. Sheldon and Lyubomirsky (2006) corroborated that changing these activities generates a higher level of happiness and a more marked change than that which occurs when circumstances are changed.

Numerous authors maintain that there are different ways to be happy (Guignon, 1999; Peterson, 2006; San Martín et al., 2010; Seligman 2002). Thus, there are different theoretical approaches to the concept of happiness, those more based on economic factors (Pigou, 1932) such as GDP, wealth level of the population etc., those that are focused on personality traits (Blanco & Diaz 2005; Veenhoven, 1994) such as neuroticism, extroversion or self-esteem, or those that are focused on socio-demographic variables such as gender, economic or educational level (Marrero et al., 2014; Valle, Beramendi & Delfino, 2011). On the other hand, Peterson et al. (2005) studied the association between different orientations to happiness with life satisfaction. With this aim, they developed a scale to measure three orientations to happiness, or in other words, three different ways to be happy: pleasure, meaning and engagement. The three all coincide with the theories about the way in which happiness may be attained: hedonism, the theory of eudemonia, and the flow, or optimal experience theory. Hedonism identifies happiness as the good or pleasurable life (Brülde, 2007; Veenhoven, 2003), which can be achieved mainly through the Epicurean principle of pleasure-seeking and pain-avoidance. Nowadays, this has even given way to the appearance of hedonistic psychology (Kahneman et al., 1999). At the same time, the theory of eudemonia associated with the orientation of meaning, has a long tradition stemming from Aristotle’s notion according to which happiness is achieved by identifying one’s virtues and developing them (Seligman, 2002). In this way, individuals hone their best aspects and use them to serve a higher purpose. According to Ryff (1989), it refers to a feeling of excellence and perfection in one’s abilities that guides the meaning and direction of his or her life. Lastly, the orientation of engagement has a more recent history and is based on Csikszentmihalyi’s (1990, 1997) theory of optimal experience, according to which subjects, through deep engagement in a developed activity, achieve a type of peak experience that the author labels optimal or flow experience. This last one is characterized by a profoundly satisfactory experience and a state of feeling very intensely and agreeably absorbed, accompanied by a loss of self-consciousness and distorted perception of the passage of time. It is precisely this experience that subjects seek when they involve themselves in these activities. To produce this experience, a series of conditions must be met, including a balance between an activity’s challenges and the subject’s abilities, a high level of concentration, and attention to a limited number of stimuli, among others.

Other authors focus on the concept of well-being, understood as a system of beliefs about the nature and experience of well-being and may be an important aspect of one’s world view (McMahan & Estes, 2011a). They assert that said concept of well-being is a complex concept that includes a great variety of beliefs and which can vary among different individuals. Some of the aspects related to well-being are the experience of happiness, a sense of purpose, wisdom, a coherent life philosophy, achievement, pleasure and love (Allport, 1961; Becker, 1992, Rogers, 1961). Despite this complexity and the numerous ways of conceptualizing well-being, these authors hold that most of them are rooted in two great philosophical traditions, hedonism and eudaimonia (Ryan & Decy, 2001). In addition, McMahan and Estes (2011a) start from the lay theories, which imply that individuals are intuitive scientists who develop and use the theories to understand, predict and control the environment (McMahan et al., 2012) and that lay conceptions in many cases coincide with the research’s approach. With regard to well-being, individuals develop their own conceptions about what well-being means for them. The importance of these conceptions is that they define a way to perceive reality, and as regards well-being, will lead them to develop a series of behaviors in accordance with the same, which, in turn, might be related to the subjects’ experience of well-being (Bojanowska & Zalewska, 2016; McMahan et al., 2013). In relation to the aforementioned, McMahan and Estes (2011a) create a scale to measure lay conceptions of the well-being of individuals along two hedonic dimensions (the experience of pleasure and the avoidance of negative experience) and two eudaimonic dimensions (self-development and contributions to others). The main contribution of this scale is that it assesses individual’s conceptions about well-being, and based on these conceptions, can lead to actions aimed at fostering the most valued experiences of well-being in such conceptions. McMahan and Estes (2011a), with a sample of university students, confirmed the existence of the four factors described above. The authors used the scale in other studies, finding that lay conceptions of well-being were found to be associated with experienced well-being (McMahan et al. 2012; McMahan & Estes, 2011b) and that these vary over time (McMahan & Estes, 2012). Furthermore, the authors point to the need to use more heterogeneous samples of the population and consider the possibility that lay conceptions of well-being differ cross-culturally. In this regard, the main objective of this study is to adapt the measure created by these authors to the Spanish population, using a sample of the general population.

Method

Participants

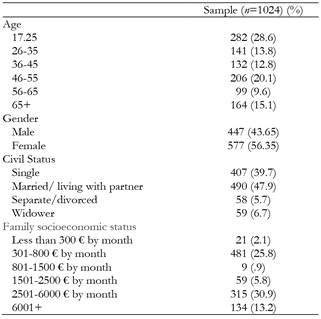

In our study, 1024 participants were selected through a procedure of random sampling with defined quotas according to sex and age, trying to get a sample of participants from different socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds, representative of the population of the city of Malaga. The age interval varied from 17 to 87 years (M = 42.11; SD = 19.56). In all, 95.8% were Spanish and 4.2% were another nationality. Table 1 summarizes the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample.

Instruments and Procedure

The surveys were administered by previously trained collaborators who received instructions about the number of participants who had to respond to the survey according to the quotas of sex and age. The participants were informed that their participation would be anonymous and voluntary. The surveys were completed individually as a self-report and the approximate time to complete them was twenty minutes. They also included a brief demographics survey together with the following scales.

The Beliefs about Well-Being Scale (BWBS), developed by McMahan and Estes (2011a), consists of 16 items which assess the degree of agreement with different matters that contribute to an experience of well-being and the good life, responding with an answer scale of 7 points (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). The scale has four factors with four items each: experience of pleasure, avoidance of negative experience, self-development and contributions to others. Some examples of items are “a great amount of pleasure”, “living in ways that benefit others” or “not experiencing hassles”. The reliability analyses of the scale in this study reveal adequate internal consistency in the four factors: experience of pleasure (Crombach’s α = .75), avoidance of negative experience (Crombach’s α =.87), self-development (Crombach’s α =.74), and contributions to others (Crombach’s α =.73).

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), created by Diener, Emmons, Larsen and Griffin (1985) consists of 5 items which measure satisfaction with life, using a Likert-type answer format, from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Some examples of this scale are “in most ways my life is close to my ideal” or “I am satisfied with my life”. In this study, Crombach’s α was .83.

The Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS), developed by Lyubommirsky and Lepper (1999), measures the subjects’ global level of happiness. The scale consists of four items. Two of them measure the subjects’ relative level of happiness compared with their peers on an answer scale of 1 to 7, where 1 means not at all happy and 7 means very happy. The other two measure the level of happiness in comparison to prototypically happy and unhappy individuals on a scale of 1 to 7, where 1 means “not at all” and 7 “very”. Some examples of items in this scale are “in general, I consider myself” or “some people are generally very happy. They enjoy life regardless of what is going on, getting the most out of everything. To what extent does this characterization describe you?” In this study, Crombach’s α was .73.

To assess personal well-being, we use the adaptation of 24 items from the Personal Well-being Scale Eudemon (PWSE), originally created in Spanish by Fierro and Rando (2007). The scale measures the degree of well-being recently experienced by people, where well-being is understood as "eudaimonic" welfare or personal fulfilment. The scale has four answer options which vary between 1 (not at all) and 4 (very). Some examples of items from this scale are “I normally wake up in the morning feeling relaxed and enthused about starting a new day,” “I add humor to life” and “I see the future as rather grim.” In this study, Crombach’s α was .89.

Data analysis

Descriptive (Table 1) and reliability tests were conducted to analyse the demographic characteristics of the sample and measure the internal consistency of the BWBS. To test the criterion validity of the BWBS, bivariate correlation analyses between between all the happiness scales’ scores used in the present study were conducted using Pearson's r statistic. To calculate the incremental validity, a hierarchical linear regression analysis was carried out. The SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corp., 2013) was used for these statistical analyses. Confirmatory factor analyses were also applied to test the factor structures of the QFSSS using the AMOS -Ver. 20.0- (Arbuckle, 2011). The CFA was carried out on both the total sample and the two resulting subsamples.

The reliability indexes were calculated using Crombach’s α index on the four theoretical factors of the BWBS scale found originally by McMahan & Estes (2011a), -experience of pleasure, avoidance of negative experience, self-development, and contribution to others-. With the aim of verifying the likely existence of a common element among these four factors obtained in the CFA, a correlational analysis was carried out among the same, using the Pearsonrstatistic. To calculate the incremental validity, a hierarchical linear regression analysis was carried out with the introducing method, in which the SHS was used as the DV. In the first step, the SWLS was introduced, in the second step, the PWSE, and in the third step, the BWBS. For the analysis of the factor structure, in order to test scale construct validity, the recommendations of Lloret-Segura, Ferrers-Traver, Hernández-Baeza and Tomás-Marco (2014) have been taken into account. Thus, once cases with lost and extreme values in any of the items of the BWBS were eliminated from the initial sample STotal (n = 1004; M age = 41.38; SD age = 19.60), sample was randomly divided into two equivalent subsamples. An Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) is applied to the first subsample, and a Comfirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) is applied to the second subsample, using the result of the first EFA as a contrast model. With the exception of the CFA, for the rest of the previous analyses the SPSS software version 22.0 (IBM Corp., 2013) was used for these statistical analyses. CFA were caried out using the software AMOS -Ver. 20.0- (Arbuckle, 2011). The convergent and discriminant validity of the proposed factorial model was also analyzed, using the Stats Tool Package (Gaskin, 2014).

Results

Structural validity

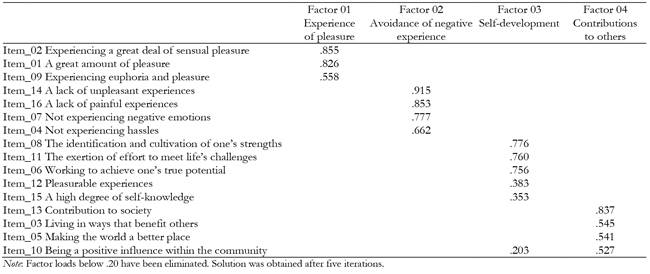

In the configuration of the applied EFA, the number of resulting factors was limited to four. This restriction was justified, as indicated above, by the factor structure obtained in the original scale. Principal axis was applied as factor extraction method and Promax with Kaiser normalization as rotation method (Osborne, 2014). The results of the EFA applied to the first SEFA1 subsample (n = 499; M age = 41.39; SD age = 20.23) are shown in Table 2.

Bartlett's sphericity test was significant (Bartlett = 3020,414, F.D. = 120, p <.001), confirming the suitability of the baseline data for the application of the factorial analysis technique. As can be seen in Table 2, the results show a factorial structure very similar to that obtained by McMahan and Estes (2011a). In this sense, the factorial loads obtained determine four groupings of items that coincide with the four factors indicated above: Experience of pleasure, avoidance of negative experience, self-development and contributions to others. However, it is observed that one of the items that initially loaded in the first factor (experience of pleasure) presents a greater load in the third one (self-development). As a possible explanation it’s suggested that under the denomination of "Pleasurable experiences" the participants have understood those in which the individual obtains satisfaction about himself and his personal development. On the other hand, item 10 presents cross loading on two factors (self-development and contributions to others). Based on the content of this item (Being a positive influence within the community), it is understandable that this cross loading should be done. However, considering the clear disparity between both factors loads (more than .3 points of difference) it is perfectly acceptable to keep this item as part of the fourth factor (Howard, 2016).

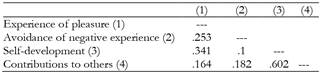

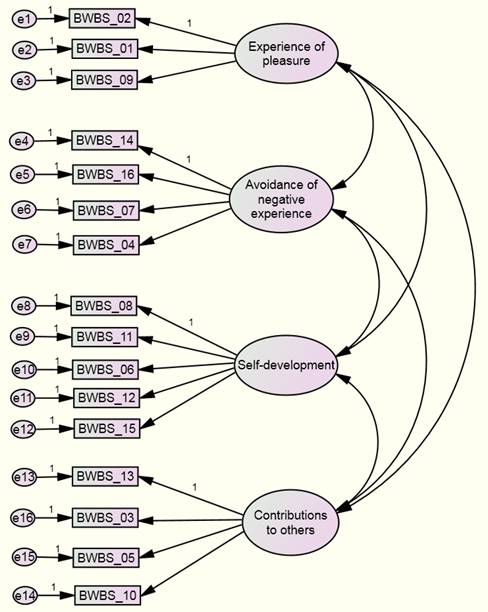

Table 3 shows the correlations between the four factors. The high correlation between the self-development factor and the contribution to others factor is noteworthy. This is understandable, given the content of the items that are part of these factors. The resulting factor structure of this EFA is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. BWBS Factor structure resulting from applying EFA to the first randomized half of participants.

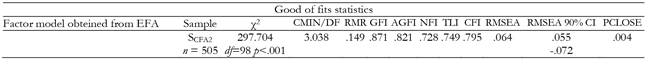

Given that the requisite of univariant and multivariant normality was not met, the asymptotically free method of estimation was used to obtain the corresponding standardized estimates in the CFA applied to the second randomised half of the sample SCFA2 (n = 505; M age = 41.37; SD age = 18.97). A bootstrap procedure was used with 200 iterations in the estimation of the parameters.

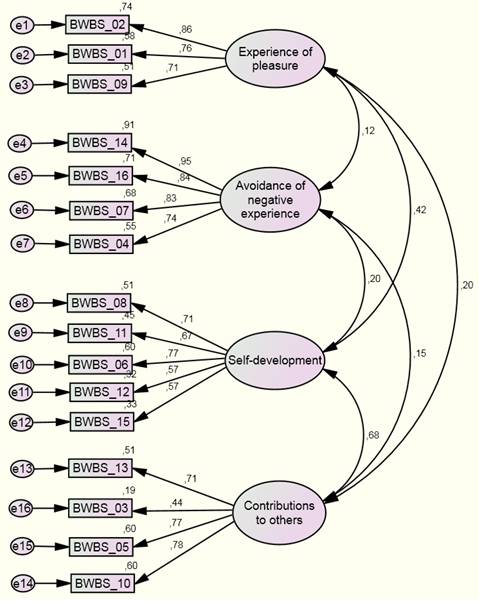

Figure 2. Standardized estimates resulting of applying CFA to the second randomized half of participants.

Figure 2 shows the standardized estimates obtained based on this second sample. As can be seen in this figure, the regression weights range obtained were quite acceptable per each factor: experience of pleasure (.71 to .86); avoidance of negative experience (.74 to .95); self-development (.57 to .71); and contributions to others (.44 to .78). The squared multiple correlations obtained for each item is above .50 with the exception of two items (3 and 15), exceeding .70 in 12 of the 16 items; which indicates a high percentage of variance explained by the corresponding factors. In relation to fit indicators (please, see Table 4)

As can be seen in Table 4, although indicators of goodness of fit are not optimal, especially in the RMR and NFI indicators, the rest of the statistics are quite adequate and enable us to affirm that this proposed model fits the data satisfactorily.

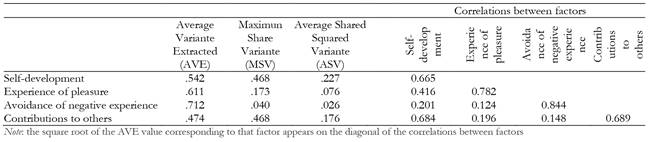

As a complement to the CFA, the convergent and discriminant validity of the proposed structure in the second model was evaluated. The convergent validity is the degree to which the indicators reflect the construct (factor or latent variable in this case), that is, whether it measures what it purports to measure. Discriminant validity implies that each factor must be significantly different from the rest of the factors that form part of the model. For this purpose, the Average Variant Extracted (AVE), the Maximum Share Squared (MSV) and the Average Shared Squared Variant (ASV) were obtained for each factor. Table 5 shows those values and the correlations between the factors. Keeping in mind the criteria contributed by Chin (1998), both the convergent and discriminant validity for the four proposed factors are confirmed. In this regard, all the square roots of the AVE values (see Table 5) are superior to the correlations among factors. As for the discriminant validity, all the AVE values of each of the factors are superior to the MSV and ASV factors (Hair, Black, Babin & Anderson, 2010), which indicates that each of these factors measure different constructs.

Score reliability

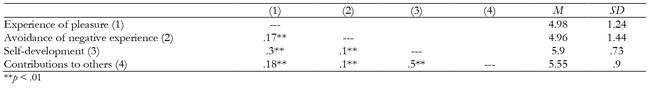

The reliability indexes of the four factors found were calculated. These analyses show adequate internal consistency, very similar to that of the original scale. The scores are the following: experience of pleasure (α = .8), avoidance of negative experience (α =.87), self-development (α =.73), contribution to others (α =.72). These results meet the requisites established by George and Mallery (2003) with regard to the fit of the α indexes found. As was expected, correlation between the four resulting factors was found (see Table 6).

Criterion validity

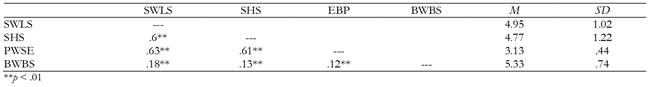

Table 7 shows the mean and standard deviation of each of the variables analyzed. A correlational analysis was conducted using the Pearsonrstatistic to assess the criterion validity of the resulting BWBS scale, of 12 items, of the validation of the original scale by McMahan and Estes (2011a) with the remaining measures of happiness used: SWLS, SHS and PWSE. All the correlations were significant (p<.01). The results show that the adaptation of the BWBS scale had a high positive correlation with the three measures used: 1) happiness (SWLS); 2) life satisfaction (SHS); and 3) personal well-being (EBH), consistent with the association expected between these variables.

Incremental validity

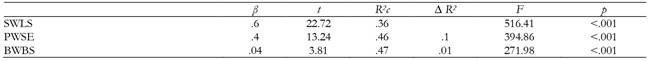

The SWLS, the PWSE and the BWBS were introduced as predictor variables in the model in the hierarchical linear regression analysis, in that order. As can be observed in Table 8, when the BWBS is incorporated, there is a significant change in the explanatory power of the model (R 2= .47; F [3.1024] = 271.98, p < .01). That is, the adaptation of the BWBS has an incremental predictive value over the SHS.

Discussion

The main aim of this study was to validate the McMahan and Estes BWBS scale (2011a) in the Spanish population to measure lay conceptions that individuals have about the concept of well-being. To this end, exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses, a reliability analysis of the different factors of the scale, correlations between the same and a regression analysis were carried out to obtain the incremental validity. In addition, this study aims to overcome some of the limitations posed by the authors for the original scale, such as the use of broader samples than those consisting of students and testing its validity within cultural contexts different from the original study.

The BWBS scale is an instrument of great interest because it provides a measure of the meaning that well-being has for people, which can entail a particular vision of reality with regard to achieving well-being (McMahan & Estes, 2011a). Likewise, individual perception of well-being might be related to behavior engaged in for achieving it and to the experience of well-being obtained (McMahan & Estes, 2011b). Furthermore, as mentioned in the introduction, at present, there is no similar scale for the Spanish population, which makes its adaptation especially relevant.

McMahan and Estes (2011a) propose that the scale be composed of two factors, hedonism and eudaimonia. Each of these factors is composed of two subfactors each: pleasure seeking and avoidance of pain in the case of hedonism, and for eudaimonia, self-development and contributions to others. The results of the exploratory factor analysis applied to half of the sample confirm the original factor structure provided by the authors of the scale. In this sense, the four original factors are maintained with the only difference that one of them (Experience of pleasure) is now composed of three items and another (Self-development) of five instead of four. This factorial model, slightly modified, has found a partial confirmation in the results of the confirmatory factorial analysis applied to the second subsample. The results of both analyses reinforce the validity of the factorial structure of the original scale adapted to Spanish.

At the same time, the version adapted to the Spanish population correlates positively with the SWLS developed by Diener et al. (1985), the SHS created by Lyubommirsky and Lepper (1999) and the PWSE developed by Fierro and Rando (2007). Lastly, the regression analysis confirms the incremental validity of the adaptation of the scale. Thus, they show a significant, albeit, modest result in relation to the incremental validity of this instrument compared with the SHS of Diener et al. (1985).

Finally, we can conclude that the results obtained in this study confirm the validity of the original scale and show that the Spanish adaptation of the BWBS scale is a valid measure for lay conceptions of well-being. The study of meaning that well-being has for individuals establishes its relationship to behavior engaged in by them to attain well-being and subjective experiences of well-being (McMahan et al., 2012). Additionally, it opens the door to transcultural studies comparing the differences in the concept of well-being between Anglo-Saxon and Hispanic stemming from cultural differences.