Introduction

Increasing lifespans in humans have led to considerable changes in family structures, with relationships spanning four generations becoming increasingly common and lasting longer (Bengtson, 2001; Troll et al., 1979).

Just as grandparents' life expectancy has increased, and with it the amount of time they spend with their grandchildren, it is logical to expect that a similar phenomenon might be observed between great-grandparents and their great-grandchildren. However, little is yet known about the role of this fourth family generation, whether it is something new or whether it is merely an extension of the prior grandparent role. Also, it is not yet known whether the theory of matrilineal advantage (Chan & Elder, 2000; Jamieson, Ribe & Warner, 2018; Thomése et al., 2008), i.e., the theory that kinship lines between grandmothers and grandchildren run more frequently through a female child than through a male child, continues here with this new family interaction, between great-grandmothers and their great-grandchildren.

Also, it remains to be seen whether this role varies between countries, as is the case with grandparents in Europe (Marečková, 2014), where differences in the number of grandparents who see their families on a daily basis can be observed between the north (Denmark, France, United Kingdom, and the Netherlands), where the mean is 22.4%, and the south (Spain, Greece, Italy, and Portugal), where it is 64.2%.

The few studies that do exist would appear to indicate that there is more continuity than discontinuity between the intrafamily roles of grandparents and great-grandparents (Castañeda-García et al., 2017; Doka & Mertz, 1988; Drew & Silverstein, 2004; Even-Zohar & Garby, 2016; Mietkiewicz & Venditti, 2004; Roberto & Skoglund, 1996), although some differences -more quantitative than qualitative- can be observed, and remain to be explored and analyzed.

It is important that new generations of grandparents acknowledge the possibility that they may be called upon to play at least one additional life role: that of the great-grandparent. Although much remains to be learned about its effects and its advantages or disadvantages, the findings of Roberto and Skoglund (1996) show that older great-grandchildren consider their grandparents (the third generation) to have had a much more defined role and exerted more influence in their lives (especially during childhood) than their great-grandparents, whose role in the family dynamics is secondary. Another study by Mietkiewicz and Venditti (2004), based on interviews with three independent great-grandparents and eight great-grandchildren, found that the role was considered to be of minor importance, even when the generations saw each other daily, as there was little verbal interaction or shared activities between great-grandparents and great-grandchildren. That study, which focused on great-grandparents and great-grandchildren who lived near each other, found that despite the scant interaction, the children showed a considerable ability to identify the signs of aging through what they observed in their great-grandparents, and that the latter played a key role in how the great-grandchildren learned about growing old.

Doka and Mertz (1988), in a study with 40 great-grandparents, identified two, opposing great-grandparent roles. The first describes remote great-grandparents who only see their great-grandchildren for special occasions and during vacations; the second describes close great-grandparents who see their great-grandchildren quite often, call them, go shopping with them, and share leisure activities with them. Great-grandparents in the latter category will even keep toys in their homes for their great-grandchildren's visits.

Another relevant study of great-grandparenthood was done by Drew and Silverstein (2004), who linked intergenerational role identities with the wellbeing of great-grandparents with living children and grandchildren. These authors found that role expectations and fulfilment had positive implications. They found that the role perception was stronger in parents and grandparents than in great-grandparents, and also showed that the role of great-grandparent was not independently correlated with wellbeing but was correlated with the other sets of roles. In other words, according to the authors, great-grandparents can be important for wellbeing above all as support figures for grandparents and parents.

Two studies have looked specifically at this evolution of the intergenerational family role, by comparing the activities previously shared between individuals and their grandchildren with the activities currently shared with their great-grandchildren (Castañeda-García et al, 2017; Even-Zohar & Garby, 2016). The finding was that, generally speaking, there were no major differences in the perception of these two successive family roles.

Thus, Castañeda-García et al. (2017) designed a study in which participants were asked specifically about this perceived difference in these same shared activities in their own homes and their grandchildren's homes, both indoors and outdoors. More than two-thirds of great-grandparents reported that they shared the same activities with their grandchildren in the past as they currently do with their great-grandchildren, albeit significantly less often, although the task was not based on shared activities volunteered by the participants but rather on a list of activities previously shared between grandparents and their grandchildren. Some sociodemographic variables, such as age and health status, were significant. The older the individual and the poorer their health status, the less frequent the interaction through such shared activities. The authors neglected to include certain relevant variables such as educational level, the distance between great-grandparents' and great-grandchildren's homes, the kinship line between the two generations in question, etc.

Even-Zohar and Garby (2016), for their part, conducted the largest study to date on this topic, with a sample of 103 great-grandparents and 111 grandparents. The two groups were compared along four dimensions: symbolic (meaning and continuity), cognitive (personal investment and personal cost), affective (negative and positive emotions), and behavioral (emotional support, instrumental support, and contribution to upbringing), and the results were related to quality of life. They found that the great-grandparent group had lower scores than the grandparent group on the four dimensions. When the role perception was high, the perception of quality of life, in both grandparents and great-grandparents, was also high.

Two possible shortcomings of the two studies have to do, first, with not having asked about whether the kinship line between great-grandparents and their great-grandchildren ran through a female or male grandchild (matrilineal advantage ) and, second, with the methodological tool employed, as it contained closed questions that assessed great-grandparents' role perception through the lens of activities taken from their prior role as grandparents. As such, they were not asked directly about which activities they share(d) with their grandchildren in the past and their great-grandchildren in the present.

We have tried to include these aspects in the present research, by means of a pilot study also conducted with great-grandparents, in which we aimed to analyze participants' social and demographic profile, the activities they share with great-grandchildren, and their perception of and satisfaction with their role as great-grandparents. The following provides a more detailed explanation of these research aims and some of the related hypotheses:

A. Sociodemographic profiling of participating great-grandparents. The aim of this section is to obtain a data set that will help characterize this group of individuals with great-grandchildren; it includes questions on age, sex, marital status, educational level, health status, possible ailments, distance at which they live from their great-grandchildren, number of children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren, and whether they live in the same household as their great-grandchildren. Another aim is to explore whether the theory of matrilineal advantage can be observed here in some way.

B. Analysis of the great-grandparent/great-grandchild interaction profile. Here the aim is to learn more about which activities are shared, with greater or lesser frequency, between great-grandparents and great-grandchildren.

C. Analysis of the relationship between the great-grandparents' sociodemographic characteristics and the interaction profile with their great-grandchildren. We expect age to be a major factor, since older great-grandparents may interact less with their great-grandchildren, especially in activities that require more physical exertion, such as school-related interactions, and the social change brought about by the use of new technologies. Educational level is also expected to nuance this interaction, as has been found to be the case for grandparents, whose intergenerational influence has been linked to their education (Mollegaard & Jaeger, 2015). Similarly, we expect that there will be less interaction for great-grandparents in poorer health, and that other factors such as the distance at which they live from their great-grandchildren, number of children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren, and whether they live in the same household or not, may be relevant factors for interaction between the two generations.

D. Analysis of the perception of the great-grandparent role and the related degree of satisfaction. Based on certain data from other studies (Castañeda-García et al., 2017; Even-Zohar & Garby, 2016), we expect to find great-grandparenthood to be perceived more as a continuation of the similar role of grandparenthood than as an intergenerational rupture.

Method

First, the choice was made to conduct a preliminary pilot study in which great-grandparents themselves would indicate, in addition to their personal data, which types of interactions they shared with their great-grandchildren and how often. A general list of intergenerational activities was used to begin with, and this was organized and ordered according to the responses we received from the participants.

Preliminary Study

Participants. A total of 10 available Spanish volunteers (five males and five females; mean age 79.3) were involved, all of whom had great-grandchildren of any age. Great-grandparents with possible cognitive decline were excluded: first the initial contacts, and then the volunteers themselves, were asked whether they suffered from memory problems or any ailment that prevented them from spending time with their great-grandchildren.

Instrument. A two-part questionnaire was used: the sociodemographic information and the interaction profile. The first part, sociodemographic information, included questions on age, sex, health status, number of children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren, and the distance at which they live from their great-grandchildren. Participants were also asked to think about and choose the great-grandchild they saw most often. Once they had made that choice, questions were asked to establish the kinship line, i.e., whether the great-grandchild in question was related through a male or female grandchild and whether, in turn, this grandchild was related through a male or female child.

The second part of the questionnaire included semi-open-ended questions about various interactive activities taken from the most common intergenerational family activity categories and spatial contexts (Castañeda et al., 2004; Castañeda-García et al., 2017; Even-Zohar & Garby, 2016; Findler et al., 2013). The following categories were obtained: Family gatherings (on which occasions), General interactions (what they do and where), Overnight stays in family members' homes (own home, child's home, grandchild's home), School-related interactions (school drop-offs, homework), Leisure and free time (various games), Long-distance communication (remote contacts), Caregiving and family help (assistance in person, assistance in kind).

In each of these categories, a general question was first asked, and if the great-grandparent provided only one response, we offered a few others which we kept to hand, noting whether the response to each was affirmative or negative, to explore as much as possible the activities being shared, as well as always adding the open-ended option “Other…” at the end of each category. This ensured that the activities piloted for the questionnaire in the main study were taken as much as possible from participant responses, based on those we proposed ourselves about this new role of interaction with great-grandchildren.

Here we present the first category as an example: Family gatherings (When do you see your great-grandchild?; after noting the response we suggested various other options, whether the response provided had been on our list or not: family meals, birthdays, Christmas, saint's days, vacations, other occasions, etc.). Another example can be seen in the last category: Caregiving and family help (Are your great-grandchildren) often left in your care?, Yes ( ), No ( ); Where?, When?, and Why?; Do you often help your great-grandchild's family out? Yes ( ), No ( ); In what ways?, with options provided by us if we did not receive many responses: with food, with money, with domestic goods, with other things, etc.).

Procedure. All participants were interviewed by the researchers in their own homes without anyone else in the room (kitchen or living room). Participants were told that the questionnaire was anonymous and that their data would be kept confidential. They were also asked to reply as honestly as possible, given that there were no right answers.

Results. For the analysis of the data from this group of n=10 we applied a frequency count. For the category Family gatherings (on which occasions they met), more than half of participants reported seeing their great-grandchildren on all the occasions provided, with the option most frequently cited being family meals (90% of participating great-grandparents or 9/10), and the option least frequently cited being the saint's day (60% of participants).

For the item under General interactions (what they do and where): “What do you do with your great-grandchild when you meet?”, walks and meals were the shared activities most mentioned by participants, at 60% and 90% respectively. Only 20% of participants, however, reported attending parties with their great-grandchildren.

For the item under the same category: “Where do you meet with your great-grandchild?”, the option most often selected was their own home, which was reported by 70% of respondents as always being the place where they met. For the option of their child's home, the option most often selected (70%) was that they sometimes met their great-grandchildren there. For the option of their grandchild's home, the results varied and the frequency reported was lower. A total of 70% of the respondents reported seeing their great-grandchildren outside the home.

With respect to the Overnight stays with great-grandchildren in family members' homes (own home, child's home, grandchild's home), 40% of participants reported spending nights with great-grandchildren in their own homes, 50% reported doing so in their children's home and 40% did so in their grandchildren's homes. The reasons given for the overnight stays varied.

For School-related interactions (school drop-offs, homework), 40% of great-grandparents reported sharing such activities (homework only) with their great-grandchildren.

For Leisure and free time (various games), considerable intergenerational interaction was observed, with 80% of participants reporting playing with their great-grandchildren. Of participants, 30% reported using gaming consoles and other devices to play with their great-grandchildren.

For Long-distance communication (remote contacts), it was found that 40% have landline telephone contact; 20% communicate by both landline and mobile telephone, and the remaining 40% have no such contact.

For the category Caregiving and family help (assistance in person, assistance in kind), in the first part 40% of participants reported caring regularly for their great-grandchildren, with 30% doing this in their own homes. The frequency of this care varied and the main reason given was the grandchildren's need to work. In the second part of this category, family help, it was found that 80% of participants contribute to their grandchildren's household. Here, 60% reported providing financial contributions, 10% said they provided food, and the remaining 10% stated that it was due to their living in the same household as their great-grandchildren.

Main Study

Participants

A group of 68 available Spanish volunteers were interviewed, all of whom had at least one great-grandchild aged two or over, to avoid possible lack of interaction as detected in the pilot study. Each participant was also asked in this main study whether they suffered from memory problems or any particular ailment (Do you have any memory or communication problems when you want to meet your grandchildren or when you are with them?). No participant was eliminated, probably given the useful initial preselection made by relatives or friends.

Instrument

The findings of the preliminary pilot study were used to design the main questionnaire, which consisted of three parts:

First part. The questionnaire on sociodemographic information was expanded to include questions about the participants' educational level; also, those who had indicated an average-to-poor health status were asked to specify ailments and medication. This part of questionnaire thus included questions on the following: age, sex, health status, number of children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren, distance at which they live from their great-grandchildren, whether they live in the same household as any of their great-grandchildren, selecting one whom they see more often, and indicating that great-grandchild's age and kinship line (whether it is through a male or female child and male or female grandchild).

Second part. For the interaction profile, the semi-open-ended questionnaire used in the pilot study was converted into a closed questionnaire with 24 questions using a 5-point Likert scale (never, sometimes, often, very often, always). To draft the items, the initial seven category blocks were used, with each containing two to four questions based on the responses that had received the most positive responses in the pilot study and which included at least one shared activity between the two generations. The following items, which had received no positive responses in the pilot study, were eliminated from the category of general interactions: seeing each other at parties, and what do you do when you are alone together. Thus, the final questionnaire consisted of the following: 2 items under Family gatherings (e.g., How often do you see your great-grandchild at family meals?); 4 under General interactions (e.g., How often do you see your great-grandchild at your grandchild's home?); 3 under Overnight stays with great-grandchildren in family members' homes (e.g., How often do you and your great-grandchild spend the night in your grandchild's home?); 4 under School-related interactions (e.g., How often do you drop your great-grandchild off at school?); 3 under Leisure and free time (e.g., How often do you play educational games with your great-grandchild: board games, painting, puzzles, etc.?); 2 under Long-distance communication (e.g., How often do you talk to your great-grandchild on a mobile phone?); 4 under Caregiving and family help, two for the former (e.g., How often is your great-grandchild left in your care?), and two for the latter (e.g., Do you offer any other type of help in your great-grandchild's upbringing?).

Third part. Five questions were added to the questionnaire, both to study great-grandparents' perception of the functions of their role (4 items) and to assess their own satisfaction with that role (1 item). In the first part, items were selected representing each of the three role types that are most described and agreed in the literature on intergenerational relationships, excluding parents, and considering the role between grandparents and grandchildren (Castañeda-García et al., 2017): one item for the formal role, a second for the informal role, and a third for the substitute or surrogate role. Thus, for the formal role it was asked: Do you think the function of a great-grandparent is to visit with and get to know your great-grandchildren whenever possible, offer support when needed, and transmit values and offer advice? For the informal role, the question was: Do you think that the function… is to not impose rules on your great-grandchildren, spoil them a bit, and have fun together?). For the third role of substitute or surrogate we asked: Do you think… should be the same as the one you had as a parent with your children? A fourth item asked whether they perceived their new role of great-grandparent in the same way as their former role of grandparent: Do you think that your function with your great-grandchildren should be the same as you had as a grandparent? These four Likert-type questions offered five possible responses (strongly disagree; disagree; neither agree nor disagree; agree; strongly agree). The fifth item asked about overall satisfaction with the great-grandparent role (e.g., Are you satisfied with your role as a great-grandparent?), with five possible responses (not at all, a little, somewhat, quite a bit and a lot) as well as asking two open-ended questions to elicit the reasons behind this satisfaction or lack thereof (e.g., Why are you satisfied with your role as a great-grandparent?).

Procedure

The conditions and instructions for administering this questionnaire were identical to those applied in the pilot study: heteroadministration was required, as it was the researchers themselves who administered it in person to the great-grandparent once verbal consent had been given. The questionnaire was to be administered in a quiet place without anyone else present. The great-grandparent was to be informed that the aim of the study was to learn about their views on their relationship with their great-grandchildren. Given the expected advanced age of the participants, particular importance was placed on administering the questionnaire in person, without rushing, and repeating questions and possible responses as often as necessary to avoid errors or misunderstandings. Also, respondents were asked to reply as honestly as possible, given that there were no right answers.

Data analysis

After the data were gathered and codified, the analyses were carried out using the statistical package SPSS v.21. First, the reliability of the questionnaire was tested. Cronbach's alpha was 0.849, indicating good internal consistency.

The variables from the sociodemographic profile were treated as independent variables. With respect to the analyses, in the sociodemographic part of the questionnaire frequency tables anddescriptive statistics were used with the data and the interactions between them. We then used the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to determine the normality of distribution of the variables studied. The results of this test showed that none of the variables followed the normal distribution curve, so we used non-parametric variables for the statistical analysis. The Kruskal-Wallis (H) test was used to test for a link between the great-grandparents' sociodemographic data and the shared activities.

Finally, frequency tables were used for the part examining the great-grandparents' views of the function of their role, and the Kruskal-Wallis test was also used here to test for a link between these views and the sociodemographic data.

Results

First aim. Sociodemographic profile of the participating sample of great-grandparents

The findings of this first aim can be summed up as follows: in the variable great-grandparents' age, we found that more than two-thirds of participants were aged between 70 and 89 (M = 79.7; SD = 7.88); as for the age of the great-grandchild chosen by the great-grandparents for the study, 55.9% were in early childhood and the remaining 44.1% were in late childhood or adolescence. Under the variable sex we found that three-quarters (76.5%) were great-grandmothers and one-quarter (23.5%) were great-grandfathers, which prohibited us from using this variable as an independent variable in the rest of the study, and also meant that any data related to the theory of matrilineal advantage had to be seen more as an exploratory tendency than as a proper result, as we will explain in the Discussion. Marital status for most of the participants was either married (50%) or widowed (45.6%). The educational level was split evenly between those without any education (50%) and those with some form of education. For health status, slightly more than half of participants (57.3%) reported being in average to poor health, with the most common ailments reported being heart disease (22.1%) or ailments related to the joints and the metabolism (19.1%). With respect to the number of descendants (children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren), two-thirds of participants reported moderate figures, with one to three children and great-grandchildren and one to six grandchildren. As for the distance between their homes and their great-grandchildren's, two-thirds reported living relatively close by, naming either the same town of residence or a nearby one. The vast majority (95.5%) do not live in the same households as their great-grandchildren. As for the kinship line linking the four generations, we found that the interaction with great-grandchildren most selected by great-grandmothers is greater (+17.6%) through their daughters, the grandmothers (58%), than through their sons, the grandfathers (41%).

Second aim. Frequency of intergenerational interaction in the different categories

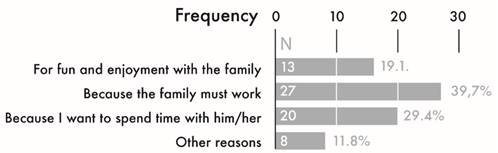

The greatest interactions between great-grandparents and great-grandchildren occur in the category Family gatherings, followed by Leisure and free time and Caregiving and family help; in third place we have General interactions and Overnight stays with great-grandchildren in family members' homes; at the bottom of the list we find the category School-related interactions (see Figure 1).

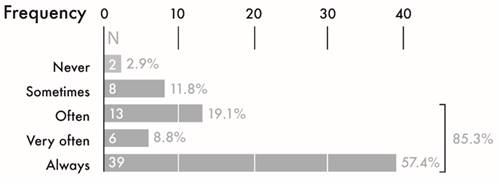

In the category Family gatherings, it was found that participants most see their great-grandchildren on special occasions (Christmas, birthdays, saint's days etc.), with 85.3% reporting doing this either “often, “very often” or “always” (see Figure 2). This is followed by family meals at 73.5%. With respect to the places where they meet, 63.2% reported always seeing their great-grandchildren in their own homes, while only 25% reported doing so in their grandchildren's homes. Fifty percent of participants reported seeing their great-grandchildren always in their children's homes, while 50% reported never doing so. Finally, 35.3% reported always meeting with their great-grandchildren outside the home.

In the category General interactions between the two generations, we can highlight that 11.8% go for walks alone with their great-grandchildren and 19.1% eat alone with them.

Figure 1. Mean frequencies and percentages of interacions between great-grandparents and great-grandchildren in most categories.

Figure 2. Interaction between great-grandparents and great-grandchildren in the following item under the Family gatherings category: How often do you see your great-grandchild on special occasions (birthdays, saint's days, Christmas, etc.)?

For Overnight stays with great-grandchildren in family members' homes, it was found that there are not very many such stays in family homes: 80.9% reported never spending the night with their great-grandchildren in their own homes, 75% never do this in their children's home and 92.6% never do it in their grandchildren's home.

For School-related interactions, the data show that 95.6% of the participants almost never help their great-grandchildren with homework. A similarly high percentage, 88.2%, reported almost never dropping them off at school. Also, 86.8% reported never picking them up from school. Twenty-five percent of the great-grandparents reported always caring for their great-grandchildren after school.

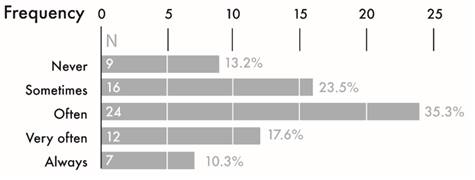

For Leisure and free time, it was found that while 63.2% of participants reported interacting with their great-grandchildren with general games, this percentage was reduced by roughly half (38.2%) when they were asked about educational games. Also, 5.9% of great-grandparents reported always using new technologies when playing with their great-grandchildren. For the frequency of interaction in this category, see Figure 3.

Figure 3. Interaction between great-grandparents and great-grandchildren in the following item under the Leisure and free time category: How often do you play with your grandchild?

For Long-distance communication, less than half always talk with their great-grandchildren. Landline use was reported by 44.1% and mobile phone use was reported by 30.9%.

For Caregiving and family help, in the first part 77.9% of great-grandparents reported never having their great-grandchildren left in their care. The reason most cited for why great-grandchildren were left in their care was the grandchildren's need to work, at 39.7%, followed by “because I want to spend time with him/her” at 29.4% and finally by “for fun and enjoyment with the family” at 19.1% (see Figure 4).

In the second part, on family help, it was found that less than half of the great-grandparents always contribute to their great-grandchild's upbringing. Further, they are more likely to provide this support by contributing food, clothing or household goods (36.8%) than by providing financial support of some kind (29.5%).

Third aim. Analysis of the relationship between sociodemographic variables and interaction categories

Great-grandparents' and great-grandchildren's ages. The youngest great-grandparents more frequently reported spending the night with their great-grandchildren in their grandchildren's home (H = 45.007, p = .022). Great-grandchildren's age. The data showed that the older the great-grandchild, the more they saw their great-grandparents outside the home (H = 34.158, p = .008), and the younger the great-grandchild, the more frequently the great-grandparents reported dropping them off at school (H = 37.432, p = .003) and picking them up after school (H = 35.393, p = .006).

Great-grandparents' health status. Great-grandparents in poorer health reported eating alone with their great-grandchildren less often (H = 8.456, p = .015). In the same vein, the poorer the health status, the less the contribution to the great-grandchild's upbringing, whether financially or otherwise (H = 8,044, p = .018).

Distance between great-grandparents' and great-grandchildren's homes. For great-grandparents, this is a major factor when it comes to taking their great-grandchild to school. Thus, the shorter the distance between homes, the greater the frequency with which they drop off (H = 11.462, p = .043) or pick up (H = 16.426, p = .006) their great-grandchild from school.

Number of children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. The data show that the fewer the children, the more often the great-grandparents see their great-grandchild in their grandchild's home (H = 17.039, p = .017).

Fourth aim. Analysis of the great-grandparents' views of the functions of the great-grandparent role and the related degree of satisfaction

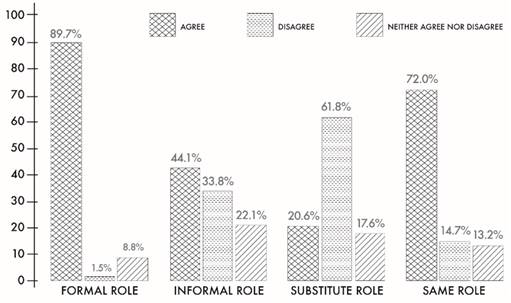

Functions of the great-grandparent role. Great-grandparents appear to be more in agreement with the functions of the formal role than with those of the informal role, and much less so with those of the substitute or surrogate role. Most see similarities between the two consecutive family roles of grandparenthood and great-grandparenthood (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Percentage agreement/disagreement of great-grandparents with the role of the great-grandparent.

Functions of the great-grandparent role and great-grandparent's educational level. The lower the great-grandparent's educational level, the more similar their perceptions of the roles of grandparent and great-grandparent (H = 9.167, p = .010), as opposed to those who reported a higher educational level.

Functions of the great-grandparent role and great-grandchild's sex. The data show differences related to the great-grandchild's sex and the views that great-grandparents hold about whether their function should be the same as the one they had as a parent to their children (substitute/surrogate role). Thus, they reported that it should be the same for great-grandsons and different for great-granddaughters (H = 8.434, p = .004).

Functions of the great-grandparent role and the related degree of satisfaction. Great-grandparents' satisfaction is related to their belief about the formal model or role, which states that the function is to visit with and get to know your great-grandchildren whenever possible, offer support when needed, and transmit values and offer advice (H = 14.480, p = .006).

Relationship between shared activity categories and degree of satisfaction. Satisfaction with the great-grandparent role is related with two of the seven categories examined. First: Family gatherings (do you see your great-grandchild at family meals (H = 16.574, p = .002); do you see your great-grandchild in your own home (H = 12.871, p = .029); … in your child's home (H = 10.752, p = .029); and second: Leisure and free time (do you play with your great-grandchild (H = 10.163, p = .038). Therefore, the more often these interactions took place, the greater the great-grandparents' satisfaction.

Discussion

In the following we will discuss the findings in the light of the stated research aims and related hypotheses.

With respect to the sociodemographic profile of the Spanish great-grandparents who participated in the study, we can observe the prototypical characteristics of a group of octogenarians, with most being married or widowed great-grandmothers, confirming the phenomenon of the feminization of aging (Maklakov & Lummaa, 2013). Half the group reported no formal education and moderately good health (one-third reported suffering heart disease or endocrine ailments), which would not appear to indicate any impediment to spending time with other generations of the family, which in this case was shown to have a limited number of members; also, while participants did not report living in the same household, they do live near their families. Another interesting finding is that when the great-grandmothers were asked to select a grandchild for the study whom they see often, most chose a great-grandchild whose kinship line runs via the great-grandparents' daughters (the grandmothers) rather than one related to them through their sons (the grandfathers), which in a way matches the theory of matrilineal advantage (Chan & Elder, 2000; Jamieson et al., 2018) between these third and fourth family generations. It would be worthwhile exploring whether this link always tends to arise between mother and daughter, irrespective of the generation in question within the kinship line. Perhaps if the sample size for great-grandmothers and great-grandfathers were to be better matched in size, we could better clarify this point; the observations made here should thus be seen more as a possible trend than as a clear result.

The results would not appear to show frequent interactions in most categories and activities. On the contrary, the great-grandparent role only appears to exist in two: Family gatherings and Leisure and free time. For Family gatherings, special occasions, both public and private, were most notable, followed, in descending order, by events in the great-grandparents', children's and grandchildren's home. This would appear to reveal a trend: the older the family member in question (here, the great-grandparents), the greater the likelihood that intergenerational gatherings would be celebrated in their home. Future studies would have to explore why the preference is to hold these gatherings in these homes. In the other category, Leisure and free time, where frequencies exceeded half of the sample, albeit with smaller majorities, general games were the most cited, which does not clarify much. It should be noted, however, that in the category Caregiving and family help, 25% of the great-grandparents reported caring for their great-grandchildren when both parents were working and one-third reported providing domestic goods and financial assistance. This possibly unexpected fact may be a sign of a new, but growing, trend towards longer working lives in which the third generation, the grandparents, who were so available until recently, are postponing their retirement and thus reducing their ability to provide such help, leaving it up to the older generation, who has most certainly already retired.

One question that arises from observing the data is whether these two most frequent interactions occur at the same time, that is to say, whether the leisure and free time activities take place at the same time as the family gatherings. If this is the case, it may be instructive to plan a future study using a new questionnaire that would explore and examine in more depth all the different types of interaction that occur at such family gatherings, both before and after the actual group activities. In this way, we could see whether there are occasions in which great-grandparents and their great-grandchildren interact on their own, and if so, which type of activities they share. It would then also be possible to determine whether the two generations interact with a third at the same time, since, according to this study, it is through other family members that great-grandparents and their great-grandchildren most often meet.

With respect to the relationship between some of the great-grandparents' sociodemographic profile data and the frequency of interaction with great-grandchildren, significant correlations were found for six activities, which were related, either directly or indirectly, to the participants' personal autonomy or mobility, as seen in their age, health status, and the distance between homes.

Thus, great-grandparents' and great-grandchildren's ages and great-grandparents' health status were shown to be relevant for 4 shared activities: eating alone with their great-grandchildren, dropping them off and picking them up from school, and spending the night in their grandchildren's home. In all these activities, it was the younger great-grandparents who had the more frequent interactions with their great-grandchildren. These results coincide with previous findings (Castañeda-García et al., 2017; Doka & Mertz, 1988). For future study designs, one might examine in more depth whether this reduced frequency in great-grandparent/great-grandchild interaction has to do with problems or limitations related to age or health status, or whether it is due to a belief that the younger generation-that of the grandparents-is more suited to carrying out these particular intergenerational activities (Bernedo Muñoz & Fuentes Rebollo, 2010).

The other relevant variable here confirms the findings of Mietkiewicz and Venditti (2004) that the distance between great-grandparents' and great-grandchildren's homes determines their interaction. In particular, the research data show that it is linked to the frequency with which great-grandparents drop off and pick up their great-grandchildren from school. The importance of distance will lead us to ask more specifically, in a future study, about the travel times between homes, and whether public or private transport is used or not. It might also be worth examining whether there are any grandparents who live closer or further away and compare the frequency of visits between the two. The other relevant variable-that of the link between the greater number of children and the frequency of great-grandparents' visits with their great-grandchildren-would appear to be linked to an increased perception of availability, as it is concentrated in a few individuals.

With respect to the views that great-grandparents hold of the functions of the great-grandparent role, we see that the results are also in line with expectations. In general terms, and in particular amongst participants with a lower educational level, the intergenerational roles of grandparenthood and great-grandparenthood are considered to be similar; however, all clearly draw a distinction between the two when it comes to more specific roles they play. Thus, only one-fifth identified with the functions associated with the substitute-surrogate role (Castañeda-García et al., 2017), in which no distinction is drawn between the parents' role and their own. On the contrary, the role cited by almost 90% of the sample as being the most appropriate for them is the formal role (Castañeda-García et al., 2017). A future study will have to examine in more depth the remarkable data regarding how the great-grandchild's sex relates to perceptions of intergenerational roles: grandparenthood and great-grandparenthood are considered to be more similar when the great-grandchild is female and less similar when it is male. Perhaps the fact that most of the sample consisted of great-grandmothers may be determining the degree of adaptation to each generation, thus leading to a different role with the two sexes, with great-grandmothers being closer to their great-granddaughters than to their great-grandsons, as has been seen with grandmothers and granddaughters (Castañeda et al., 2004; Triadó et al., 2000).

Given the distance between the generations, it would seem logical that this type of relationship be perceived as more likely to arise, although, as we have seen, one-fifth of the sample does play a caregiving role with their great-grandchildren because the parents have to work, which really is more of a substitute/surrogate role, at least when it is permanent, which does not seem to be the case here. It might be interesting to look more closely at the self-perception of the great-grandparent role as it plays out in these three forms, to determine which characteristics are constant or variable and how they are linked to personal factors or external circumstances. Might the role of great-grandparent be more flexible than that of grandparent, in that it can fulfil opposing functions depending on the circumstances of the other family generations?

The advantages of this study include the fact that the great-grandparents themselves, on two successive and complementary occasions (pilot and main studies), formed the basis of the work, as the researchers directly elicited their interactions with the great-grandchildren they see most often. Also, the final sample was larger than in any other study with this generation, which did not exceed fifty great-grandparents as participants (Castañeda-García et al., 2017; Doka & Mertz, 1988; Drew & Silverstein, 2004; Mietkiewicz & Venditti, 2004; Roberto & Skoglund, 1996), with all the advantages this entails in terms of methodology, although with an even larger sample it would have been possible to use other, complementary statistical tests.

One of the difficulties we encountered was finding locally-based great-grandparents who were willing to participate and who also met the two criteria for inclusion: that they showed no cognitive decline and that their great-grandchildren were over two years old. Another limitation, linked to the first, was the difference in the number of male and female participants available; future studies of great-grandparenthood could use more similar sample sizes for both sexes. Then there is the socioeconomic factor, which recent studies have shown to be important (Hällsten & Pfeffer, 2017).

To conclude this study of this poorly understood family role, we can say that this group of great-grandparents see great-grandchildren above all at family gatherings, for celebrations involving family members or for special occasions. The frequency of this contact depends on their age and that of their great-grandchildren; their health status; the distance between their homes; and the number of children they have. Their perception of the intergenerational relationship of great-grandparenthood is similar overall to that of the prior role of grandparenthood, although, unlike the latter (Bernedo Muñoz & Fuentes Rebollo, 2010), it is assigned the functions typical of the formal role, and it is associated with greater satisfaction.

If great-grandparenthood is to become an increasingly common phenomenon in our societies, it is important that we continue analyzing and investigating the implications of this new role in different families, to better understand the makeup of today's intergenerational relationships. Great-grandparents may already be playing a certain role involving intrafamily support for their great-grandchildren and by extension also for the parents, their grandchildren.

A better understanding of this generation of great-grandparents can also offer us insights into the new role of active aging (Doka & Mertz, 1988), which has been identified by the United Nations and the World Health Organization as a priority for the elderly in the 21st century.