Introduction

Power is defined as the asymmetric control over valuable resources in social relationships (Dubois, Rucker, & Galinsky, 2015). Power has been playing a vital role in people's lives since ancient times. Think about the emperors in the feudal society, who almost controlled all high-quality resources in their realms, such as nature, manpower, or even violence. They were thus definitely the most powerful individuals. Conversely, ordinary people could not even possess or control land resources on which they lived. Hence, they were typical low-power individuals. As the society develops, the influence of power has deeply penetrated people's daily lives. Moreover, a person's power state varies quickly in the modern society, which serves as an emerging character of power. For instance, a student is usually a low-power individual in class because he or she needs to follow the teacher's instructions. However, the student can turn to be a high-power individual when organizing events after class as a society leader who is in charge of student activities.

Since its universality and mutability, power has attracted many psychologists' attentions. The research on power, therefore, has been growing rapidly in the past decades, especially on the topic of power's downstream psychological consequences. For example, scholars have found that people with high power are more likely to possess illusory sense of control (Fast, Gruenfeld, Sivanathan, & Galinsky, 2009), to take risks (Anderson & Galinsky, 2006), and to be action orientated (Galinsky, Gruenfeld, & Magee, 2003). The low-power individuals, on the other hand, are more prosocial and more willing to spend on others (Rucker, Dubois, & Galinsky, 2011). They also perceive less time availability (Moon & Chen, 2014) and prefer to compensate for the lack of power through status consumption (Rucker & Galinsky, 2008).

Loneliness refers to the discrepancy between an individual's desired and achieved levels of social relations (Peplau, 1982). There are two types of loneliness: social loneliness and emotional loneliness (Weiss, 1973). Social loneliness arises from inadequate social networks, while the cause of emotional loneliness is the lack of close attachment relationships (Weiss, 1973; DiTommaso & Spinner, 1997). Although interpersonal interactions and communications have become easier as technology keeps advancing, people feel increasingly lonelier than before (Yzer & Southwell, 2008; Schirmer & Michailakis, 2015). Since humans are social animals who heavily rely on interpersonal relationships, loneliness can be particularly aversive that leads to extremely negative impacts on individual's physical and psychological health. Researchers found that feelings of loneliness would result in depression (Wei, Russell, & Zakalik, 2005), decreased well-being (Caprara & Steca, 2005), and even higher risk of cardiovascular diseases (Caspi, Harrington, Moffitt, Milne, & Poulton, 2006). Therefore, a body of literature has explored the predictors of loneliness. For instance, research shows that high trust beliefs decrease loneliness by promoting social interactions (Rotenberg et al., 2010). Similarly, gratitude, a positive emotion that enhances well-being, mitigates individuals' feelings of loneliness (O'Connell, O'Shea, & Gallagher, 2016). In addition, unmet need for belonging was proved to be one of the main factors that induce loneliness (Mellor, Stokes, Firth, Hayashi, & Cummins, 2008).

Though a large of body of research has focused on the consequences of power and antecedents of loneliness (e.g., Anderson & Galinsky, 2006; Fast et al., 2009; Moon & Chen, 2014; O'Connell et al., 2016), few scholars explored the potential relationship between sense of power and loneliness. Do individuals' power feelings affect loneliness? If so, how does sense of power influence perceived loneliness? What is psychological process of the effect? When does this effect hold? The present paper aims to answer these open questions.

Based on prior studies, this research proposes that sense of power decreases loneliness (Hypothesis 1), and that perceived social support mediates this relationship (Hypothesis 2). Two streams of literature provide support for these hypotheses. First, high-power individuals can receive more social support. According to PAC (power-as-control) Model, the essence of power is control (Fiske, 1993). Furthermore, Power-Dependence Theory points out that the control within a social system is a zero-sum game, such that powerful individuals' control over the powerless equals to powerless individuals' dependence on the powerful (Emerson, 1962). Consequently, high-power people always access important social resources and occupy dominant positions, being at the center in social networks. When they need support, they can usually receive timely responses. Therefore, compared with the powerless, high-power people can get more social support.

Second, receiving more social support can mitigate loneliness. Social support refers to the social resources that are provided to individuals who are suffering from stress through social relationships (Cohen, 2004). Theoretically speaking, when people receive social support, they will be surrounded by the warmth from their families and friends rather than feeling as an isolated person. Empirically, social support has been shown as an effective buffer against life stress (e.g., Wilcox, 1981; Montes-Berges & Augusto, 2007). Consistently, researchers find that social support contributes to psychological well-being independent of adversity levels (e.g., Brewin, MacCarthy, & Furnham, 1989; Zhao, Kong, & Wang, 2013). In line with these findings, social support can also mitigate the negative feelings when individuals are lonely because it effectively makes up deficiencies of social relations (Ell, Nishimoto, Mediansky, Mantell, & Hamovitch, 1992).

However, the relationship between sense of power and loneliness cannot hold all the time. Since receiving more social support renders high-power individuals less lonely, it could be argued that as individuals perceive less social support, or even social exclusion, sense of power may be less effective in mitigating loneliness. Social exclusion is defined as one person is put into a condition of being excluded from desired relationship or being devalued by desired relationship partners or groups (MacDonald & Leary, 2005). Social exclusion can cause a series of negative effects. Previous studies have shown that social exclusion produces anxiety (Baumeister & Tice, 1990), stress related disorders (Wang, Braun, & Enck, 2017) and impairs immune system organs (Cacioppo, Cacioppo, Capitanio, & Cole, 2015). For students, social exclusion is associated with low affective well-being, high possibilities of mental health problems and disadvantages in academics and social skills (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Arslan, 2018). For office workers, perceived social exclusion increases interpersonal deviance, withdrawal behaviors and lower performance (Robinson, O'Reilly, & Wang, 2013). In line with these findings, we predict that the relationship between sense of power and loneliness is moderated by social exclusion in such a way that sense of power reduces loneliness more effectively when social exclusion is low than when it is high (Hypothesis 3). Specifically, high power mitigates loneliness effectively when social exclusion is absent. However, as people who are socially excluded are either rejected or ignored by other social members, neither high- nor low-power individuals can perceive or receive social support. Therefore, the buffering effect of sense of power on loneliness ceases to exist.

Study Overview

We designed and conducted two studies to test the hypotheses. Study 1 is a survey study in which we tested Hypothesis 1 (Sense of power decreases loneliness) and 2 (Perceived social support mediates the relationship between sense of power and loneliness). Study 2, using an experimental approach, seeks to provide causal evidence for Hypothesis 1 and to examine Hypothesis 3 (The relationship between sense of power and loneliness is moderated by social exclusion). Moreover, we also used sample sources from different cultural backgrounds (i.e., Chinese participants in Study 1 and American subjects in Study 2) to verify the generalizability of the findings.

Study 1: A Survey Study

Methods

Participants

Study 1 used the survey method to test our hypotheses. Data were collected from a sample of 539 participants in China using Sojump (http://www.sojump.com), which is a professional online survey platform similar to Qualtrics, containing more than 38.8 million users with different demographic characters. Sojump has been widely used in previous psychological research (e.g., Li, Chen, & Huang, 2015; Wang, Li, Sun, Cheng, & Zhang, 2017). Among the participants, 229 were males, and 310 were females. All of the respondents were adults. Among the respondents, 63, 33, and 4% of them were 18-35, 36-53, and above 54 years old, respectively. 38 and 47% of the respondents' monthly salary ranged from 2000 to 4000 yuan and from 4001 to 6000 yuan, respectively. The majority of the sample was well-educated: 45, 20, and 5% of them held bachelor's degrees, master's degrees, and PhDs as their highest degrees, respectively.

Instruments

All measures used in this study were originally developed in English. To ensure the accuracy of translation, the items of the scales were first translated into Chinese by a native Chinese speaker who is also proficient in English, and were back-translated into English by a native English speaker with excellent knowledge of Chinese. The back-translated version was then compared with the original one (Brislin, 1970). Inconsistencies were resolved by discussion between the two translators and the researchers.

Sense of power was assessed by the Sense of Power Scale (Anderson, John, & Keltner, 2012), an eight-item scale measuring participants' general sense of power in their social relationships. Participants rated the extent to which each item applied to them on a seven-point scale (1 = disagree strongly, 7 = agree strongly). An example item is, “In my relationships with others, I can get him/her/them to listen to what I say.” We averaged the eight items to create the score of sense of power (Cronbach's alpha = .88).

Perceived social support was evaluated through the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) (Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, & Farley, 1988), a 12-item scale measuring different sources of social support (i.e., family, friends, and significant others). On a seven-point scale (1 = very strongly disagree, 7 = very strongly agree), participants reported their agreement with each item. A higher score indicates that the participant receives more social support. An example item is: “There is a special person with whom I can share my joys and sorrows.” The items were averaged to create the score for perceived social support (Cronbach's alpha = .82).

We measured loneliness using the UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3) (Russell, 1996), which consists of 20 items. It has been widely used in previous research and has shown good reliability and validity. Participants were asked to indicate how often they experience the feelings described by each item. A sample item is: “How often do you feel that your interests and ideas are not shared by those around you?” (1 = never, 4 = always). A higher score shows that the participant feels lonelier. All items were averaged to create the score for loneliness (Cronbach's alpha = .89).

In this study, we also controlled for demographic variables (gender, age, education, and income) of participants, which are potentially correlated with loneliness (Page & Cole, 1991; Sundstrom, Fransson, Malmberg, & Davey, 2009; Yang & Victor, 2011).

Procedure

Respondents were recruited from Sojump using its sample service (Li et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2017). We set the task bonus as 5 yuan (i.e., .73 dollar). In 24 hours, 539 workers on Sojump participated in our project. Before the survey, all the participants were told that their responses would remain confidential. At the end of the questionnaire, we asked whether there were technical barriers during responding. As promised in the task description, the bonuses were awarded to all the participants within one week after completing the survey. We checked the data and found all participants responding within reasonable time intervals.

Data análisis

We first performed a series of confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) to examine the validity of scales using R Studio version 3.2.4. A series of indicators were chosen for evaluating the model fit, including the chi square to df ratio, CFI, NNFI, and RMSEA. Correlation analyses were adopted to provide initial evidence for research hypotheses. Then we used multiple regressions and bootstrapping method (Hayes, 2013) to further test our hypotheses. SPSS 20.0 software was used in these statistical analyses. Fisher's z and R2 were calculated as effect sizes (Cohen, 1988).

Results

Validity and correlation analysis

Results suggested that the three-factor measurement model yielded a better fit (χ 2/df = 1.21, CFI = .95, NNFI = .93, RMSEA = .08) compared with three competitive models: The two-factor model combining sense of power and perceived social support (χ 2/df = 5.65, CFI = .86, NNFI = .87, RMSEA = .18), the two-factor model combining sense of power and loneliness (χ 2/df = 22.13, CFI = .82, NNFI = .83, RMSEA = .22), and the two-factor model combining perceived social support and loneliness (χ 2/df = 29.55, CFI = .81, NNFI = .80, RMSEA = .25).

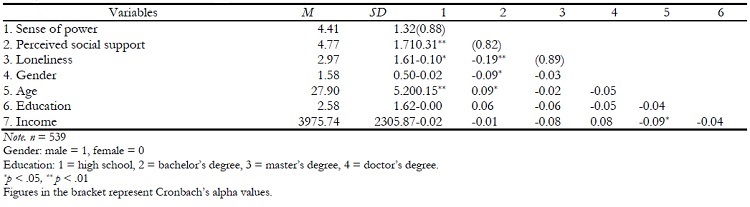

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and correlations among the study variables. The results provide preliminary support for our hypotheses. More specially, sense of power was positively related to perceived social support (r = .31, p < .01, Fisher's z = .32) and negatively related to loneliness (r = -.10, p < .05, Fisher's z = -.10). Perceived social support was negatively correlated with loneliness (r = -.19, p < .01, Fisher's z = -.19).

Test of hypotheses

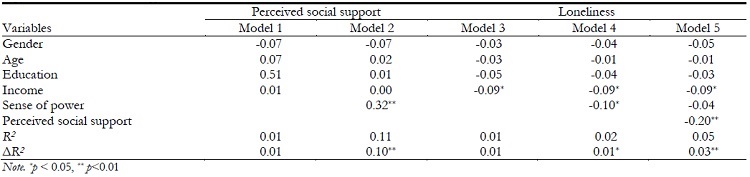

First, even after controlling for demographic variables, we still found a significant and negative main effect of sense of power on loneliness (β = -.10, p < .05, R 2 = .49, Model 1), supporting Hypothesis 1 (Sense of power decreases loneliness). Then, we found that sense of power showed a significant effect on perceived social support (β = .32, p < .01, R 2 = .90). Finally, when perceived social support was added to Model 1, it exhibited a significant and negative effect on loneliness (β = -.20, p < .01, R 2 = .87). Since the coefficient of sense of power was no longer significant (β = -.04, ns, R 2 = .09), the results indicated that perceived social support mediates the relationship between sense of power and loneliness (see table 2 for a summary), thus supporting Hypothesis 2 (Perceived social support mediates the relationship between sense of power and loneliness).

Moreover, bootstrapping analyses further supported that sense of power influences loneliness via perceived social support (95% CI (-.11, -.03)). The mediation of perceived social support accounted for 51.00% of the total effect (MacKinnon, Warsi, & Dwyer, 1995). Taken together, these results provide convergent evidence for Hypothesis 2 (Perceived social support mediates the relationship between sense of power and loneliness).

Study 2: Testing the Causal Relationship and Moderation

Methods

Participants and design

Study 2 sought to provide causal evidence for Hypothesis 1 and to examine Hypothesis 3. One hundred thirty-seven undergraduate students from a large public university in the United States participated in the study. They were in the subject pool of the university. Of the total subjects, 49.64% (n = 68) were men and 50.36% (n = 69) were women. The average age of the sample was 22.56 years old (SD = 2.87). As for the academic year, 59.12% (n = 81) of the participants were in their second year, and 40.88% (n = 56) in their third. 55.47% (n = 76) of them majored in natural science, and 44.53% (n = 76) studied humanistic and social science. Participants were randomly assigned to conditions in a 2 (power: high vs. low) × 2 (social exclusion: exclusion vs. control) between-subjects design.

Procedure

Participants were unaware of our research objectives. They were first engaged in the manipulation of power and social exclusion, and then completed the measurement of loneliness. For the manipulation of power, participants were asked to imagine how they would feel and act given a role related to high or low power (Rucker et al., 2011). Participants in the high-power condition were told a situation in which they had power over others as a boss at company. They were not only in charge of managing the subordinates but also evaluating them. In contrast, participants in the low-power condition were told that they must follow the instructions of the boss as an employee. In addition, they had to be evaluated by the boss privately. Thereafter, the participants completed the manipulation check question, which was a one-item scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) that indicated how powerful they felt (e.g., “I feel powerful.” ; Mooijman et al., 2015).

Social exclusion was manipulated through an episodic priming task (Su, Jiang, Chen, & Dewall, 2017). By random assignment, participants recalled either a situation in which they felt social excluded or what happened to them yesterday. Upon completing the recall paradigm, the participants were told to report the extent to which they felt “excluded” during the situation (1 = not at all, 5 = very much; Su et al., 2017). Afterward, all participants answered a one-item state loneliness question (“Do you experience loneliness?”; Holmen, Ericsson, & Winblad, 1999). They were thanked and debriefed after completing all the tasks. After checking the debriefing materials, we found that no subject figured out the intentions of the experiment.

Data análisis

Analyses of variance (ANOVA) were used for data analysis. We further adopted planned contrasts as post-hoc tests to reveal the differences of conditions. We used SPSS 20.0 software in these statistical analyses. Partial eta-squared (η²) is calculated as the evaluation of the effect size. The cutoff value for defining a small, medium, and large effect is .01, .06, and .14 respectively.

Results

Manipulation check

We first validated the manipulation of power and social exclusion. Consistent with our expectation, the participants in the high-power condition felt more powerful (M high = 3.51, SD = 1.20) than those in the low-power condition (M low = 2.99, SD = 1.35; F (1,135) = 5.45, p < .05, η² = .04). The ANOVA on sense of power revealed no significant main effects of social exclusion or interaction effect. Similarly, an ANOVA on perceived social exclusion yielded that the participants in the social exclusion condition felt more explicitly excluded (M excluded = 3.41, SD = 1.22) than those in the low-power condition (M low = 2.84, SD = 1.20; F (1,135) = 7.83, p < .01, η² = .06). Neither the main effect of sense of power nor the interaction effect emerged. Taken together, these results confirmed the success of the power and social exclusion manipulation.

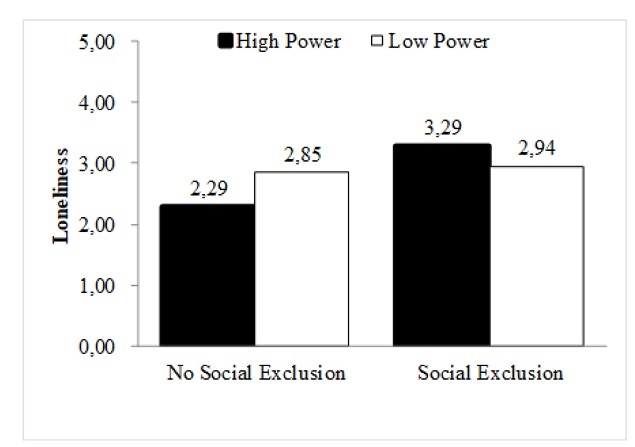

Test of hypotheses. A pair of 2 (power: high vs. low) × 2 (social exclusion: exclusion vs. control) between-subject analyses of variance (ANOVAs) was used to analyze the effects of sense of power and social exclusion on loneliness. The results revealed that individuals who were socially excluded felt lonelier than those who were not conceptually replicated previous studies (Jones, 1990; Leary, 1990). Importantly, this effect was qualified by interaction between sense of power and social exclusion (F (1,133) = 5.06, p < .05, η² = .04). The planned contrasts showed (see Figure 1) that when social exclusion was absent, the high-power participants (M high = 2.29, SD = .94) felt less lonely than the low-power participants (M low = 2.85, SD = 1.29; F (1,133) = 4.04, p < .05, η² = .06), which provided causal evidence for Hypothesis 1(Sense of power decreases loneliness). However, this effect disappeared under the social exclusion conditions such that there was no significant difference in loneliness between the high-power and low-power participants (M high = 3.29, SD = 1.24; M low = 2.94, SD = 1.17; F (1,133) = 1.44, ns, η² = .01), thus supporting Hypothesis 3 (The relationship between sense of power and loneliness is moderated by social exclusion).

Discussion

Theoretical contributions

This research investigated how sense of power affects individual's loneliness. We also examined the mediating role of perceived social support and the moderating role of social exclusion. Across two studies, we found that sense of power can reduce loneliness, and that perceived social support serves as the underlying mechanism in this relationship, and that this effect is mitigated under the social exclusion condition.

This paper finds an increased sense of power could reduce loneliness, which is consistent with the extant literature (Galinsky et al., 2003; Anderson & Galinsky, 2006). Prior research has revealed a series of psychological benefits of being powerful. For example, gaining power reduces individuals' conformity and helps them act in line with their willingness. Power can also increase self-authenticity, which in turn enhances subjective well-being (Kifer, Heller, Perunovic, & Galinsky, 2013). Our research further finds that sense of power can significantly reduce loneliness. Therefore, we add knowledge to the burgeoning literature on the positive functions of power (Emerson, 1962; Fiske, 1993).

Furthermore, previous literature has documented that loneliness is aversive and that the two direct approaches to get rid of loneliness are rebuilding existing social networks and creating new ones by making friends (Weiss, 1973; Peplau, 1982). The present research contributes to this body of literature by showing that loneliness can also be suppressed indirectly by promoting one's sense of power. Through the mediation test, this research found that sense of power alleviates loneliness by enhancing perceived social support. We therefore complement previous findings regarding how social support mitigates life stress (Wilcox, 1981; Montes-Berges & Augusto, 2007) and boosts well-being (Brewin et al., 1989; Zhao et al., 2013) by highlighting the role of social support in buffering loneliness.

Moreover, this research showed that social exclusion can moderate the relationship between sense of power and loneliness. When there is no social exclusion, sense of power can alleviate loneliness. However, when social exclusion exists, no matter high-power or low-power individuals feel lonely. Prior studies mainly focused on the antecedents of loneliness from the perspective of either interpersonal (e.g., need for belongingness; Mellor, Stokes, Firth, Hayashi, & Cummins, 2008) or contextual factors (e.g., uncooperative organizational climate; Lam & Lau, 2012). This research shows that loneliness is jointly affected by both contextual factors (e.g., social exclusion) and interpersonal factors (e.g., sense of power), when the effects of power can be mitigated (Narayanan, Tai, & Kinias, 2013).

In addition, our findings also contribute to Self-Determination Theory (Ryan and Deci, 2000), which points out three fundamental human needs: need for competence, need for relatedness, and need for autonomy. If any of the three needs have not been fully satisfied, an individual's mental health could be at risk. Self-Determination Theory has been an important research topic since proposed. However, most extant studies examined the effects of these three needs separately (e.g., Broeck et al., 2010; Fernet et al., 2013; Ruzek et al., 2016). Few of them explored the potential connection between different needs. The current research shows that the three needs are not completely independent. Instead, they are internally related with each other. For instance, a high-power individual's need for competence and autonomy are generally satisfied because of the high position in the social hierarchy. Meanwhile, as sufficient social support is present, a high-power person is less likely to be lonely. Therefore, his or her need for relatedness is also satiated.

Practical implications

This paper reveals that sense of power and social support, as two important and positive psychological resources, could effectively alleviate loneliness. These findings are practically useful in two ways. First, to avoid being lonely, individuals can reinforce their power feelings. A couple of convenient ways were shown to be able to promote power states. For example, giving advice is an interpersonal behavior that can enhance individuals' senses of power (Schaerer, Tost, Huang, Gino, & Larrick, 2018). Second, in terms of the mediating role of social support, people can turn to their families and friends for care and warmth when being lonely. In another way, people should offer help and support to their friends and relatives whenever necessary, to prevent others from being lonely.

Limitations

Despite using two different samples and methods, our research still has some limitations that point out future research directions. First, although we tested the mediating effect of perceived social support, alternative explanations may still exist. We encourage future research to investigate whether other psychological factors can serve as potential underlying mechanism through which sense of power alleviates loneliness. Moreover, since perceived social support has not been manipulated in the current research, the causality from perceived social support to loneliness remains an open question (Spencer, Zanna, & Fong, 2005). Second, we only identified the moderating role of social exclusion. Future studies could test other boundary conditions to provide a more comprehensive understanding of when sense of power decreases loneliness. Third, it should be noted that assumptions may underlie the findings in this paper. For example, one who feels powerful based on subjective perceptions can deviate from a person that truly lives in power circles. In a similar vein, feeling alone is not absolutely equal to being isolated. Future studies can adopt behavioral measures to further validate self-reported data.

Conclusion

To sum, the present paper shows that: (1) Sense of power reduces loneliness. (2) Perceived social support mediates this relationship, such that power enhances perceived social support and thereby decreases loneliness. (3) Social exclusion moderates this relationship, such that the buffering function of power is effective only when social exclusion is absent.