Introduction

Emotional dependence on a partner can be defined as a pattern of unmet emotional and affective needs that attempt to be met in a maladaptive way through interpersonal relationships (Urbiola et al., 2017). These people manifest an intense terror of abandonment, of loneliness (Sirvent & Moral, 2018), of ceasing to be loved and of feeling less of a priority (Castelló, 2019). Likewise, they show negative thoughts about themselves, low self-esteem, insecurity, the need to have a partner to feel complete, great difficulty in facing life on their own (Markez, 2015), a sense of emotional emptiness and negative feelings, such as discouragement and sadness (Moral et al., 2018). This is why they place the partner in a predominant place in their lives (Castelló, 2019) and put in place a wide range of withholding strategies in order to maintain the relationship at all costs, such as, acquiring behaviors of submission and extreme obedience (Riso, 2014), passive adaptation to the partner, lack of initiative (Sirvent & Moral, 2018) and constant and excessive demands for attention, affection and closeness (Izquierdo & Gómez-Acosta, 2013) that are suffocating and are never enough to alleviate the anxiety experienced. Thus, they experience feelings of frustration as the longed-for expectations are not met (Markez, 2015), showing loss of identity (Riso, 2014), feelings of not being free and, ultimately, dissatisfaction with the relationship as they feel they will never get what they want from it. Despite this, they are unable to break the relationship, showing a behavioral pattern of repeated breakups with their subsequent returns to the relationship (Skvortsova & Shumskiy, 2014).

Emotional dependence is considered one of the factors involved in the permanence of violent relationships (Momeñe & Estévez, 2018), as it could make it difficult to break the relationship (Izquierdo & Gómez-Acosta, 2013). Paradoxically, people who are victims of intimate partner violence mention remaining in love with their aggressors regardless of the severity of the violence received (Castelló, 2005). Thus, people with emotional dependence follow a pattern of establishing pathological and unbalanced intimate partner relationships (Castelló, 2012).

Partner violence presents a high incidence and relevance (Fernández-González et al., 2017), with women reporting a higher risk of suffering it (Peitzmeier et al., 2016). It can manifest itself through three different forms; psychological, physical and sexual (Echeburúa, 2018; Lee & Lee, 2018). Psychological violence is the most prevalent (Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi et al., 2016), can occur independently or precede physical violence and is the most difficult to identify. The violence exercised increases in frequency and intensity over time (Del Castillo et al., 2015), since, once the first violent episode has arisen and the inhibitions linked to respect for the partner have been broken, the probability of it being repeated and used as a way of controlling the relationship for increasingly insignificant reasons is greater (Echeburúa & Muñoz, 2017).

For its part, intolerance to uncertainty is defined as a tendency to perceive uncertain and ambiguous situations as negative, unpleasant, unacceptable and threatening, regardless of the probability of their occurrence, which leads them to react to them in an intense and negative emotional, cognitive and behavioral way, as well as to avoid them (Morriss & McSorley, 2019; Radell et al., 2018; Rodgers et al., 2019; Roma & Hope, 2017). Likewise, difficulty tolerating uncertainty poses some risk by increasing the likelihood of engaging in risky behaviors aimed at alleviating distressing or unpleasant emotions (Sadeh & Bredemeier, 2019). Therefore, due to the high presence of uncertain situations in everyday life, the negative consequences it brings and its presence in various clinical manifestations, recent studies have mentioned the relevance of its study (Lauriola et al., 2018; Tanovic et al., 2018). Moreover, intolerance to uncertainty plays a key role in the etiology and maintenance of worries (Chen et al., 2018; Osmanağaoğlu et al., 2018), sometimes excessive and uncontrollable (Gonzalez et al., 2006b) and even pathological (Kusec et al., 2016). The tendency to experience worries can be defined as a repetitive pattern of excessive thoughts or ruminations about negative or unpleasant aspects that are directed toward the future and difficult to control. Worries interfere and generate significant impairment and discomfort in relevant areas such as family, social and occupational functioning (González et al., 2006). However, there are people who consider them necessary and use them to increase a sense of control, analyze problems in depth, generate a range of potential solutions and thus be able to prevent negative consequences (Rausch et al., 2011). In this sense, people with difficulties in tolerating uncertainty, in addition to using repetitive thoughts such as worries and ruminations, experience pessimistic ideas about future events (Yook et al., 2010).

Along these lines, pessimism has been defined as a tendency to see and judge things negatively. Moreover, pessimistic people consider that unpleasant events will persist for a long time, believe that they cannot do anything to change the situation and attribute the mistakes or negative aspects to themselves (Seligman, 2011). Thus, this pessimistic thinking prevents the emission of behaviors to cope with adversities and consequently, the experience of failure increases pessimism (Lemola et al., 2020). Following the approach of Peterson & Seligman (1984) on the pessimistic explanatory style, they agree that pessimistic people tend to explain negative events as an internal cause, which is stable over time and globally affects all areas of life. In contrast, the optimistic explanatory style is defined as a tendency to explain negative events as a cause external to oneself, unstable over time and specific to that particular area. Moreover, they believe that they are able to exercise behaviors to resolve negative situations and achieve positive results in the future (Carver & Scheier, 2001). Therefore, optimism is related to the expectation that positive events will occur in the future, whereas pessimism is related to the expectation that negative events will happen in the future and has been related to several mental health disorders (Peres et al., 2019).

Consequently, no studies are found that analyze intolerance to uncertainty, tendency to worry, and pessimism in people with emotional dependence. Despite this, the behaviors that characterize people with emotional dependence have aspects in common with the factors indicated. Due to the negative repercussions, they produce in daily life and their possible interference in treatment, it is necessary to study them. The underlying hypothesis would propose that emotional dependence would be positively related to intolerance to uncertainty, tendency to worry and pessimism. Furthermore, these factors would mediate the relationship between emotional dependence and intimate partner violence. Therefore, these hypotheses would be tested through two objectives. The first would aim to analyze the relationship between the study variables and the second to examine whether intolerance of uncertainty, worry proneness, and pessimism are potential mechanisms underlying the association between emotional dependence and staying in violent relationships.

Method

Participants

A total of 258 persons participated in the present study, 77.1% women and 22.9% men between 18 and 67 years of age (M = 32.63; SD = 11.66). Participants born in Spain predominated, making up 88% of the sample. With regard to educational level, 76.4% were studying or had studied at university at the time of participating in the study, 19.4% had studied vocational training and 4.3% had studied primary school. Regarding relationships, 77.5% were in a relationship at the time of participating in the study, while 22.5% did not have a partner. Regarding sexual orientation, 83.7% defined themselves as heterosexual, 13.2% as bisexual, 2.3% as homosexual and .8% as other.

Instruments

Emotional dependence. Emotional Dependence Questionnaire (CDE; Lemos & Londoño, 2006). It evaluates emotional dependence in the context of couple relationships. It contains 23 items divided into 6 scales: separation anxiety, evaluates the emotional expressions of the fear that is produced by the possibility of the breakup of the relationship; affective expression, is aimed at evaluating the need to have constant expressions of affection from the partner that reaffirm the love they feel for each other and that calms the feeling of insecurity and anxiety; modification of plans, analyzes the change of activities, plans and behaviors due to implicit or explicit desires to satisfy the partner or the simple possibility of sharing more time with the partner; fear of loneliness, evaluates the fear of not having a partner relationship and feeling that he/she is not wanted; limit expression, evaluates the impulsive actions or manifestations of self-aggression in the face of a possible breakup of the relationship since it can be catastrophic due to his/her confrontation with loneliness and the loss of meaning in life; attention seeking, evaluates the active search for attention by the partner to ensure his/her permanence in the relationship and to try to be the center of attention in his/her partner's life. The response format is Likert-type with 6 response alternatives ranging from 1 ("Completely untrue of me") to 6 ("Describes me perfectly").

The total questionnaire presents a high internal consistency, obtaining a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of .93 (Lemos & Londoño, 2006). In the present study, Cronbach's alpha coefficient for the global scale was .95.

Intimate partner violence received. Revised Conflicts Tactics Scale-2 (CTS2-Revised Conflicts Tactics Scale-2; Straus et al., 1996). This scale evaluates the violence exercised and received in intimate partner relationships and the use of negotiation as a method of conflict resolution. The scale is made up of 78 items, of which 39 items are aimed at analyzing the actions performed by the person answering the questionnaire, while the other 39 items are aimed at analyzing the actions performed by the partner. It contains five scales: negotiation, which refers to the actions taken to end a disagreement through discussion and reasoning. This scale is divided into two subscales: cognitive, which evaluates these discussions, and emotional, which evaluates the extent to which the couple communicates positive affective feelings and encourages expressions of affection and respect. The rest of the scales listed below are also divided into two subscales, minor and severe. The physical aggression scale refers to physical violence. The psychological abuse scale includes acts of verbal and nonverbal violence. The sexual coercion scale assesses behaviors aimed at forcing a partner to engage in unwanted sexual activity. Finally, the injury scale measures physical harm inflicted, such as broken bones, need for medical assistance or continued pain. The scale consists of 8 response alternatives indicating the number of times a violent act has occurred in the last 12 months (0 "Never", 1 "Once", 2 "Twice", 3 "Three to five times", 4 "Six to ten times", 5 "Eleven to twenty times", 6 "More than twenty times" and 7 "Not in the past year, but previously"). It also presents 4 indicators: Prevalence (it is dichotomous (0 - 1), indicating whether the acts have occurred or not); Chronicity (it refers to the number of times an act of a scale has occurred); Lifetime prevalence (it takes as a temporal reference the entire life of the person completing the questionnaire); Annual frequency (it weighs the items of each scale by their frequency of occurrence).

In the present study, the items aimed at assessing physical and psychological violence received by the partner will be used.

The total scale of violence received has shown good psychometric properties in the Spanish adult population, obtaining a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of .83. In this way, the victimization subscales have also obtained good internal consistency, negotiation (α = .75), physical aggression (α = .80), psychological abuse (α = .73), sexual coercion (α = .63) and injuries (α = .69) (Graña et al., 2013). In the present study Cronbach's alpha coefficient for the physical aggression scale was .94 and for the psychological abuse scale it was .90.

Intolerance to uncertainty. Intolerance to Uncertainty Scale (EII; González et al., 2006a). It evaluates intolerance to uncertainty, emotional and behavioral reactions to ambiguous situations, implications of insecurity and attempts to control the future. It is composed of 27 items divided into two subscales: inhibition-generating uncertainty, referring to the way in which uncertainty generates insecurity, stress and disturbance; uncertainty as bewilderment and unpredictability, referring to the need for certainty that arises in the person intolerant to uncertainty when affected by unforeseen events. The response format is Likert-type with 5 response alternatives ranging from 1 ("Not at all characteristic of me") to 5 ("Extremely characteristic of me").

It obtained a Cronbach's alpha coefficient for the global scale of .95 (inhibition-generating uncertainty α = .93; uncertainty as bewilderment and unpredictability α = .89). In the present study, Cronbach's alpha coefficient was .96 for the global scale, .95 for the inhibition-generating uncertainty subscale, and .92 for the uncertainty as bewilderment and unpredictability subscale.

Worries. Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ-11; Sandin et al., 2009). It assesses the general tendency to experience worries. It is composed of 11 items with a Likert-type response format ranging from 1 ("It is not at all typical for me") to 5 ("It is very typical for me").

The questionnaire obtained a good internal consistency showing a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of .92. In the present study Cronbach's alpha coefficient was .95.

Optimism. Optimism Questionnaire (COP, Pedrosa et al., 2015). It consists of 9 items with a 5-point Likert-type format ranging from 1 ("Strongly disagree") to 5 ("Strongly agree"). The positively formulated items were recoded to obtain the pessimism scale.

Cronbach's alpha coefficient was .84. In the present study, Cronbach's alpha coefficient was .87.

Procedure

This was an exploratory and quantitative cross-sectional study.

Collaboration in the study was solicited online through various social networks over a 6-month period and participants were recruited following the snowball sampling technique. They were provided with a link to access the study divided into several sections. In the first section they received information on the general characteristics of the study: objective; to deepen their knowledge of couple relationships, voluntariness and anonymity of the answers given, importance of sincerity, inclusion criteria; to be over 18 years old and to have had at least one couple relationship, duration, contact of the researchers, etc. The second section included sociodemographic data and the third section included the battery of questionnaires selected for the study.

All participants signed an informed consent form prior to participation in the study. In addition, the present study made sure to follow the ethical principles established by the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 2013).

Data analysis

First, bivariate relationships between emotional dependence and physical and psychological violence received, intolerance to uncertainty, tendency to worry and pessimism were analyzed by means of Pearson's r. Next, a three-step linear regression model (Baron and Kenny, 1986) was performed to analyze a mediation model that included intolerance to uncertainty, tendency to worry and pessimism as hypothesized mediators in the relationship between emotional dependence and physical violence received, as well as, in the relationship between emotional dependence and psychological violence received. In the first step, emotional dependence should be statistically significantly related to intimate partner violence received. In the second step, emotional dependence should be significantly associated with the mediating variables. In the third step, the relationship between emotional dependence and violence received should decrease as the mediating variables are introduced into the model. Likewise, all mediation analyses were performed controlling for the variables sex and age. The effect of mediation was evaluated using the bootstrapping procedure that provides 95% confidence intervals.

Results

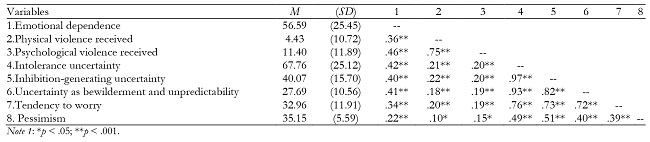

First, the relationships between the study variables were analyzed (Table 1).

Emotional dependence was positively related to intimate partner violence received, especially psychological violence, intolerance to uncertainty, tendency to worry and pessimism.

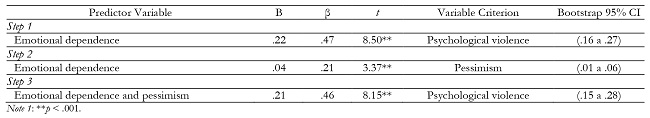

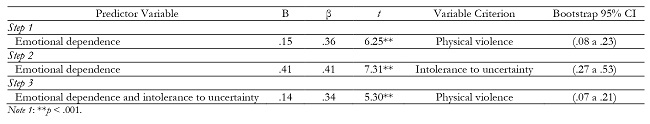

Secondly, the mediating role of intolerance to uncertainty in the relationship between emotional dependence and physical and psychological violence received was analyzed. The statistically significant data obtained are shown in Table 2.

Emotional dependence was statistically significantly associated with physical violence. The results obtained suggested that 6.67% of this relationship was explained by intolerance to uncertainty.

Table 2 Mediation model including emotional dependence (X), intolerance to uncertainty (M) and physical violence received (Y)

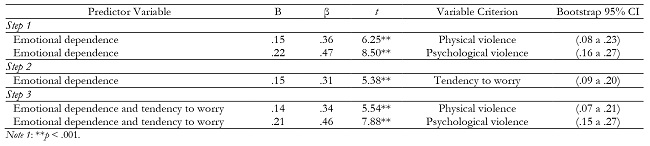

Next, the mediating role of the tendency to worry in the relationship between emotional dependence and physical and psychological violence received was analyzed (Table 3).

Emotional dependence was significantly related to physical and psychological violence and the tendency to worry explained 6.67% and 4.54% of these relationships, respectively.

Table 3 Mediation model including emotional dependence (X), tendency to worry (M) and physical and psychological violence received (Y)

Finally, the mediating role of pessimism in the relationship between emotional dependence and physical and psychological violence received was analyzed. The statistically significant results are shown below (Table 4).

As can be seen, emotional dependence led to permanence in psychologically violent relationships and pessimism explained 4.54% of this relationship.

Discussion

The first objective was aimed at analyzing the relationships between the study variables. The results showed that emotional dependence increased in parallel with intolerance to uncertainty, the tendency to experience worry and pessimism. To the authors' knowledge, studies aimed at analyzing these relationships are nonexistent. Despite this, the results obtained related to intolerance to uncertainty could be explained through previous studies that mention the use of controlling behaviors by emotionally dependent people towards the partner (Petruccelli et al., 2014). In addition, they show a great need to know at all times what they are doing and with whom their partner is with, which may result in continuous and excessive phone calls and appearances in inappropriate places (Castelló, 2005). Along these lines, when faced with the perception of a possible abandonment by the partner, generated by situations such as an argument, a delay in the schedule or when faced with the verification of the existence of other priorities or significant people in their lives, they set in motion all kinds of maneuvers in order to avoid any type of distancing. In these cases, they may impose certain rules for the functioning of the relationship that would provide them with security as they feel they are in control of the relationship and of the prevention of abandonment of the partner (Markez, 2015). The data obtained related to the tendency to experience worries would be in line with studies that mention that people with emotional dependence experience extreme and constant worries related to possible abandonment or betrayal by the partner (Castelló, 2019). In this way, they present high ruminations or intense worries about the deterioration, rupture or abandonment of the relationship and their consequent loneliness. As a result, they live their relationships with great anxiety and restlessness (Castelló, 2005). Regarding the relationship between emotional dependence and pessimism, these results are in line with studies that mention that a lower sense of control over the couple relationship leads to the development of negative moods in people with emotional dependence (Markez, 2015). Likewise, the presence of affective maladjustments in the form of negative feelings in people with emotional dependence has been pointed out (Sirvent & Moral, 2018) along with the feeling of chronic emotional emptiness and desires for self-destruction (Moral et al., 2018).

The second objective of the study focused on evaluating the mediating role of intolerance to uncertainty in the relationship between emotional dependence and physical and psychological partner violence received. The results obtained reported a significant relationship between emotional dependence and physical violence received. In this regard, intolerance to uncertainty explained part of this relationship. These results can be explained by the fact that people with emotional dependence present controlling and dominant behaviors over the partner, continuously demanding attention and affection with the aim of controlling the relationship and ensuring the partner's permanence in it (Aiquipa, 2012). These behaviors could be reminiscent of the intense reactions to ambiguous situations characteristic in people with intolerance to uncertainty (González et al., 2013). In addition, uncertain and unexpected situations, as is the case of possible abandonment by a partner, exhaust and disturb them and they believe they can avoid it (Rodríguez de Behrends & Brenlla, 2015). For its part, attachment theory could explain the relationship between intolerance to uncertainty and remaining in violent partner relationships since the anxious-ambivalent attachment style established in childhood, characteristic in people who remain in violent relationships, acts as a predictor of intolerance to uncertainty in the future (Zdebik et al., 2018). Another explanation, could be based on the fact that intolerance to uncertainty has been strongly associated with generalized anxiety (Gillett et al., 2018) and it has been mentioned that people with higher levels of internalizing symptoms such as anxiety may be more vulnerable to establish or remain in violent relationships (Novak & Furman, 2016). In this regard, it has been mentioned that intolerance to uncertainty could play an important role in the development and maintenance of a wide range of emotional disorders (McEvory & Carleton, 2016).

The third aim of the study was to examine whether the tendency to experience worry mediated the relationship between emotional dependence and physical and psychological violence received. The data obtained corroborated such mediation. This may be due to the fact that people with emotional dependence are characterized by reflecting great concern in their faces, constant nervousness and anguish (Castelló, 2005). To calm the anxiety they feel, originated by the worries related to the abandonment of the partner, they demand continuous and intense displays of attention and affection that are never enough nor fulfill their objective of calming the anguish they experience (Markez, 2015). Apart from concerns concerning the partner, people with emotional dependence manifest a tendency to anxiety and worry in situations that require them to be independent or to function autonomously (Bornstein, 1996). In addition, these results could also be explained through the social learning theory. This theory postulates that emotional dependence is learned by imitation (Bandura, 1960). In collation with this, the origin of emotional dependence has been related to an overprotective parental parenting style (Scantamburlo et al., 2013) characterized by presenting high and frequent worries (Kalomiris & Kiel, 2016). Thus, people with emotional dependence may be repeating that behavioral pattern of a tendency to parental-learned worries. As for staying in violent relationships, these results can be explained by returning to the previously mentioned attachment theory. The anxious-ambivalent attachment style established in childhood through interactions with attachment figures, in addition to predicting permanence in violent relationships, predicts the tendency to present obsessive concerns about the partner, possible abandonment or separation, high anxiety and constant vigilance (Feeney & Noller, 2001).

The last objective of the study was to test the mediating role of pessimism in the relationship between emotional dependence and physical and psychological violence received. The results showed that pessimism explained part of the relationship between emotional dependence and psychological violence received. In this regard, this could be explained by the fact that the relationships established by people with emotional dependence are full of emotional oscillations and feelings of pain, sadness, despair, absence of freedom and of not having a choice. They feel a great dissatisfaction with the relationship, however, they are unable to break it because the loneliness that this would entail would generate a much greater suffering than the suffering they experience by remaining in it. They assume that they will never get what they want from that relationship, but they cling to it, moving in a vicious circle of continuous breakups and returns to the relationship (Skvortsova & Shumskiy, 2014). In addition, it has been mentioned that people with emotional dependence present negativity about themselves (Markez, 2015) and a negative habitual mood that is characterized by deep sadness, unhappiness and personal insecurity regardless of their circumstances (Castelló, 2005). Thus, they present a generalized dissatisfaction with life (Bornstein et al., 2004). In this line, previous studies have mentioned that emotional dependence would be a predictor of anxious and depressive symptomatology (Estévez et al., 2017). Likewise, previous studies have reported higher scores in the early dysfunctional schema of negativity/pessimism in people who suffer intimate partner violence compared to people who do not (Huerta et al., 2016). This dysfunctional schema established in childhood and associated with permanence in violent relationships reflects beliefs that things will go bad or get worse, focusing attention on negative aspects and minimizing or ignoring positive or optimistic aspects (Young et al., 2013). Along these lines, it has been found that women with greater depressive symptoms are more likely to suffer violence in their intimate partner relationships (Gonzalez-Guarda et al., 2013; Keenan-Miller et al., 2007; Lehrer et al., 2006).

The present study is not without limitations. On the one hand, the cross-sectional nature of the study makes it impossible to obtain causal relationships. On the other hand, people with emotional dependence have a tendency to deny the problem, which may have influenced the data obtained (Moral-Jiménez & González-Sáez, 2020). In addition, self-report measures run the risk of suffering from social desirability bias. For its part, the snowball sampling employed has some disadvantages when it comes to generalizing the results. In future studies it would be interesting to analyze the results using a clinical sample, i.e., people who have experienced violence.

In conclusion, the results obtained are relevant and of great clinical importance. This is due to the absence of studies analyzing the relationship between emotional dependence and intolerance to uncertainty, the tendency to experience worry and pessimism. In addition, no studies have been found that analyze the mediating role of these factors in the relationship between emotional dependence and permanence in violent relationships. These analyses are very important due to the transcendence of emotional dependence in violence (Martín & Moral, 2019). In terms of clinical implications, it has been found that people who present emotional dependence towards their partner show intolerance to uncertainty, tendency to experience worry and pessimism. These factors may influence the treatment and maintenance of dysfunctional relationships. Therefore, they may be relevant constructs to take into account both in individual therapy and in couple therapy and it is necessary to work on them and include them in the treatment to improve the results.

texto en

texto en