Introduction

Professionals and researchers in the field of Pedagogy and Educational Psychology agree that joint and coordinated work is required among the various agents in the educational community (Andrés & Giró, 2016; Epstein, 2001; Garreta, 2017) for student development and school success (Álvarez, 2019; Azpillaga et al., 2014). Therefore, research on school, family and community collaboration looks at joint ways of working with the family, school and community, to improve the education of children and society overall (Epstein, 2013); contemplated from the regulatory framework (BOE, 2006; Comisión Europea, 2000).

From the Effectiveness and School Improvement approach, the aim is to transform the day-to-day working of the school by gathering solid knowledge for educational change, leading to development of all students by optimizing schools´ teaching-learning processes and organizational structures. An effective school is understood as "one that achieves the comprehensive development of every student, beyond that foreseeable based on prior performance and the socio-economic and cultural situation of their families" (Murillo, 2005, p. 30). From this standpoint, schools with students who have much lower development than expected can be deemed ineffective.

Several studies identify common features linked to the processes and particularities of the most effective schools (Rivas & Ugarte, 2014; Sammons & Bakkum, 2011) while others (Hernández-Castilla et al., 2013; Silveira, 2016) examine factors that determine some, "ineffective schools" or "negative prototypical" ones, which obtain results below expectations. Through synthesis, Hernández-Castilla et al. (2013), mention school factors connected to student development which, whether positive or negative are related to school effectiveness or ineffectiveness: a) Sense of community; b) Educational leadership; c) School and classroom climate; d) High expectations; e) Quality of curriculum and teaching strategies; f) Classroom organization; g) Monitoring and assessment; h) Professional development of teachers, understood as an attitude toward continuous learning and innovation; i) Family involvement; and j) Facilities and resources.

Common features of successful experiences in family-school collaboration are (Consejo Escolar del Estado, 2015): a) Cooperative work in a climate of dialogue and mutual trust, a belief that mothers and fathers must participate in important school decisions such as formulation of the school´s educational project; b) Adopting a proactive rather than reactive role in collaboration; c) Developing actions to achieve involvement of all parents, thus working specifically with some families is required, taking into account their particular circumstances; d) Collaboration formulas adapted to the various educational stages are proposed; e) Dedicating time and effort to motivate and train all sectors involved (families, school management team, teachers and the rest of the educational community); f) Collaboration with families is more a matter of quality than quantity, with strategic planning aimed at deepening realistic and flexible forms of collaboration.

Theoretical models of family participation are as follows: 1) The Ecological Systemic Model (Bronfenbrenner, 1986); 2) Model of Overlapping Spheres of Influence (Epstein, 1990); 3) “Syneducation” Model (Mylonakou & Kekes, 2005); 4) Causal and Specific Model of Parental Involvement (Hoover-Dempsey & Sandler, 1995); 5) Motivational Model and Multidimensional Conceptualization (Grolnick & Slowiaczek, 1994) and 6) Hierarchical Bipyramidal Model (Hornby, 1990). These can be complementary and all adopt a systemic approach based on a diagnostic process to identify risk and protection factors to enhance both academic achievement and performance and prevent school dropout (Álvarez, 2019). Deslandes (2019) proposes an integrating model, an extension of that of Hoover-Dempsey and Sandler (1995), which includes parental motivational processes and the school system, as well as personal, family and educational characteristics, school-family collaboration and personal factors associated with the youngest students. This is a tool aimed at the main stakeholders so they can reflect on and improve family-school collaboration in addition to supporting research analyzing factors and processes involved in development and improvement.

This research aims to examine relationships that, according to teachers, school management teams and educational inspection, are established between the family-school-community in primary schools of the Basque Autonomous Community (BAC) characterized by different school effectiveness-ineffectiveness criteria. In order to achieve this, among theoretical proposals for family-school-community collaboration, the Epstein model (2001) is adopted as it is the most widely used due to its influence on policies and practices developed in various countries (Álvarez, 2019). From this model, type of participation offered to families is identified and classified into six options: 1. Parental support and training; 2. Communication; 3. Volunteering; 4. Home learning; 5. Decision-making; and 6. Community collaboration. Assessing the importance teachers place on parental involvement is considered, according to the prediction model of parental involvement in the education of sons and daughters (Grolnick & Slowiaczek, 1994), and within the level of school contextual analysis.

Teachers and school management teams are highlighted in various studies and by the educational community as promoters and enablers of participation (Consejo Escolar del Estado, 2015; Rivas & Ugarte, 2014). However, some studies in Spain (Gomila et al., 2018) and other European countries (Alanko, 2018; De Bruïne et al., 2018; Epstein, 2018; Mutton et al., 2018) report teachers feel insufficiently prepared for collaborative work with families and the community and point out gaps in initial teacher training and professional development (Willemse et al., 2018).

Differences have been found between effective and ineffective schools based on variables related to teaching staff. According to Rivas and Ugarte (2014), the teacher´s role is mediated by their own perspectives as well as by possibilities offered by the school, particularly training, which is often scarce (Andrés & Giró, 2016). Besides pedagogical-didactic and personal aspects, sensitivity to family needs is among the most important competences of teaching staff (Lewis et al., 2011). As with fathers and mothers, teachers´ attitudes toward collaboration exert a strong influence on family-school relationship dynamics (Garreta, 2017; Gomila & Pascual, 2015). In this regard, Andrés and Giró (2016) found that in all schools (private and public), teachers are open, flexible and willing to adapt to families' time preferences. Armas (2012) however, found teachers at concerted private schools perceived greater family participation than those from public schools.

Teacher training is key in achieving school success (Jarauta et al., 2014; Lizasoain et al., 2016). According to the Spanish Report, International Study of Teaching and Learning, TALIS 2018 (Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional, 2019), 43% of primary teachers have taken part in professional development activities on cooperation between parents/guardians and teachers, while 29% of school principals admit to a "great need" for training on how to encourage and develop collaboration among teachers.

Another investigated aspect is the relationship between teaching experience and school effectiveness/ ineffectiveness, and it has been suggested that this may have a greater effect on a student´s academic outcome than for instance their socio-economic level (Darling-Hammond, 2016).

At this stage, what is teachers´ perspective regarding family involvement? Research results are not conclusive, some indicate they often receive support from families (Cárcamo & Garreta, 2020; Martínez-González et al., 2012) while others (Belmonte et al., 2020; Cooper et al., 2006) highlight little collaboration and that it is generally mothers rather than fathers involved in school matters (Fernández-Freire et al., 2019; Fúnez, 2014).

Professionals require a favorable participatory school climate largely fostered by the school management team through shared leadership involving the entire educational community in achieving the aims of the school organization, promoting interaction and participation (Cunningham et al., 2012; Donohoo et al., 2018) which then contributes to school effectiveness and improvement (Rivas & Ugarte, 2014). A participatory culture in the educational center involves a school management team that promotes training of teachers and families in this field, including all in the decision-making process (Epstein et al., 2011). Furthermore, the school must be sensitive toward current family changes and particular circumstances, enabling their relationship through strategies adjusted to each situation. Moreover, given that ethnicity, social origin and financial situation influence the differential participation of families, schools must adopt a non-homogeneous participation model that attends to the socio-geographical-family diversity of students (Grijalva et al., 2020; Hernández et al., 2016; Miller, 2019).

Taking all this into consideration, the aim of this research is to examine similarities and differences in the family-school-community collaboration of schools with different levels of effectiveness in the Basque Autonomous Community (BAC) and, ultimately, to identify good practices which bring school improvement. Specific aims are as follows:

Learn the assessment which Primary Education (PE) schoolteachers in the BAC have regarding family-school-community collaboration actions, and their relationship with personal variables and school effectiveness criteria.

Examine the perception which teachers, school management teams and educational inspection of PE schools have regarding family-school-community collaboration according to the effectiveness criteria of the school where they work.

Method

This work forms part of broader research on school effectiveness and improvement, based on Diagnostic Evaluation (DE) collected over five editions in the BAC, with the collaboration of the Basque Institute for Research and Evaluation in Education (ISEI-IVEI). It is a study with descriptive-exploratory-explanatory design and mixed methodology. Through interviews with school management teams and educational inspection, as well as discussion groups with teachers and completion of a questionnaire, several areas related to high-low school effectiveness were investigated, including family-school-community collaboration.

Participants

From Primary Education schools in the BAC (N = 409), classified according to effectiveness criteria (Lizasoain, 2020) which will be explained in the Procedure section, 23 public and concerted schools took part, 11 high-effectiveness (HE) and 12 low-effectiveness (LE), specifically: 1) three Extreme High Residuals (EXT HIGH RSD); 2) eight Increase in Residuals (INC RSD); 3) four Extreme Low Residuals (EXT LOW RSD); and, 4) eight Decrease in Residuals (DEC RSD).

208 teachers participated voluntarily in the quantitative study (38 EXT HIGH RSD, 82 INC RSD, 16 EXT LOW RSD and 72 DEC RSD). In total, apart from 15 teachers (7.21%) for whom data is unavailable, 147 were women (70.67%) and 46 men (22.12%), mean age 44.10 (SD = 9.87) and mean years of teaching experience 19.53 (SD = 10.56). The school management teams (SMT) and educational inspection (EI) corresponding to the 23 schools took part in the qualitative study, as well as 22 female and 10 male teachers who participated in 7 discussion groups (DG), specifically: 2 EXT HIGH RSD, 3 INC RSD, 0 EXT LOW RSD, and 2 DEC RSD).

Instruments

The semi-structured interview with school management teams and educational inspection addresses 8 areas related to School Effectiveness and Improvement (training and innovation projects and plans; methodology; attention to diversity; assessment; school organization and management; leadership; climate; and family- school-community) however, in this work only information on the school´s relationship with families and community is gathered, as well as good practices developed. In addition to collecting aspects related to Epstein´s six types of parental involvement (2001), it enquires about attention to family diversity and problems or complaints. The script for discussion groups with teachers is aimed at learning how they value, and what, from their viewpoint, explains results obtained by the school. This involves collecting their view of educational reality (schools´ strengths, weaknesses, difficulties and educational practices) so improvement plans can be designed and implemented.

Teachers completed an ad hoc online questionnaire to gather information on 8 areas related to School Effectiveness and Improvement mentioned in a previous R&D Project. The questionnaire was reviewed by experts for reliability and validity and reduced to a total of 92 items (α = .97) with an average completion time of fifteen minutes. This article analyzes 10 items (rated from 0 to 10) on the subject of family-school-community relations (α = .90), specifically: in the last year difficulties in relations with families were satisfactorily addressed; the school adapts to family needs; families are generally satisfied with the school; the school only contacts families when difficulties arise; teachers encourage family involvement in the teaching-learning process at home; families are involved in school activities; participation of families in the school's decision-making is favored; the school carries out concrete initiatives to involve fathers in the education of their sons and daughters; the school collaborates with local groups and associations; and, generally values family-school community relations. All items were written based on a previous theoretical review that includes Epstein's (2001) proposal.

Procedure

Research was conducted in several phases. In Phase I, based on an initial census study analyzing data from all schools in the BAC, educational centers were selected which met certain previously established characteristics based on criteria of high (HE) or low effectiveness (LE), with the control of the effect of contextual variables on scores through multilevel statistical regression procedures using hierarchical linear models (Lizasoain, 2020).

A school is deemed highly effective (or "ceiling effect") when it obtains a higher score than expected, that is, a positive differential or residual score after subtracting the influence of contextual variables (network, size and Socio-economic Index (SEI) of the educational center, rate of repeating students, rate of migrant students) in the average of the three basic instrumental skills (Spanish language, Basque language and mathematics) obtained by 4th grade primary students from five years of DE application. When done in reverse, these are considered low- effectiveness schools (or "floor effect"). In addition to the "ceiling effect" and "floor effect" schools, that is, extreme residuals with high (EXT HIGH RSD) and low effectiveness (EXT LOW RSD) respectively, also considered were those that increased (INC RSD) or decreased (DEC RSD) in residuals throughout five years of DE.

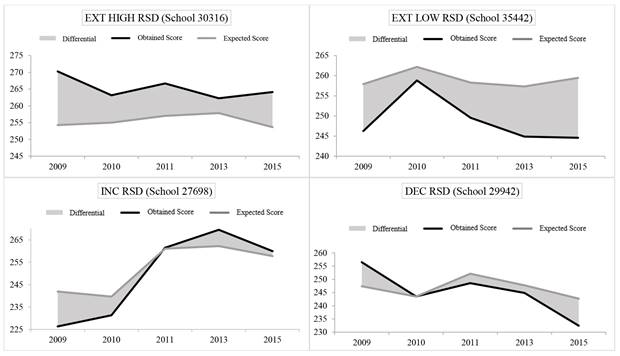

Figure 1 shows an example of each type of school, with the average score of the three competences assessed in the five DE measurements, and contextual characteristics (in percentile score) are as follows: school 30316 has a size of .60, SEI .54, immigration rate .59, repetition rate .51; school 27698 has a size of .75, SEI .54, immigration rate .71, repetition rate .35; school 35442 has a size of .97, SEI .85, immigration rate .03, repetition rate .39; school 29942 has a size of .49, SEI .22, immigration rate .60, and repetition rate .60. The four schools form part of the concerted network.

Phase II: To better understand their characteristics; semi-structured interviews were carried out with key informants, management teams and educational inspection, subsequently categorized into 8 areas linked to school effectiveness. This work focuses on information in the field of family-school-community relations. Finally, based on collected data, in Phase III, teachers from selected schools completed an ad hoc questionnaire using Google forms. Discussion groups were also held.

Quantitative data were analyzed using the SPSS 26 program. Once schools were chosen according to effectiveness criteria through multilevel regression statistical procedures (hierarchical linear models), descriptive analyzes (Mean and Standard Deviation) were used for questionnaire data and non-parametric tests (Mann-Whitney for comparison of means of two groups and Kruskal-Wallis for more than two) following verification that data did not follow normal distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Qualitative data analysis was conducted using the NVivo program. Researchers coded content independently from interviews and discussion groups based on prior established categories and/or emerging nodes, showing a high degree of convergence. Once categorization was done, matrix coding queries and coding comparison queries were performed to check Cohen's Kappa index according to inter-rater agreement (k = .89).

Results

Teachers´ assessment according to personal factors and school effectiveness criteria

As regards gender, female teachers score higher than their male counterparts in the following items: The school adapts to family needs (immigration, diversity of family models, use of ICT, social exclusion...) (M (SD) = 7.84 (1.66) vs 7.37 (1.65); Z = -2.123; p = .034); Teachers favor family involvement in the teaching-learning process at home (M (SD) = 7.66 (1.51) vs 7.19 (1.32); Z = -2.389; p = .017). Teachers over 45 years of age versus those under, largely consider the school only contacts families when difficulties arise (M (SD) = 6.89 (2.60) vs 5.93 (2.67); Z = -2.506; p = .012) and that family participation in decision-making at the school is favored (M (SD) = 6.95 (1.82) vs 6.31 (2.06); Z = -2.179; p = .029). In terms of of teaching experience, teachers active for over 19 years (compared to those under) largely consider the school only contacts families when difficulties arise (M (SD) = 6.89 (2.60) vs 5.93 (2.67); Z = -2.506; p = .012).Likewise for teachers who have worked longer (over 12 years) at the school versus those working for fewer years (M (SD) = 6.90 (2.57) vs 5.82 (2.78); Z = -2.778; p = .005). Teachers´ overall assessment of the school regarding family-school-community relations is higher for those employed at the school for longer (over 12 years) (M (SD) = 7.70 (1.35) vs 7.05 (1.74); Z = -2.495; p = .013) than those for fewer years.

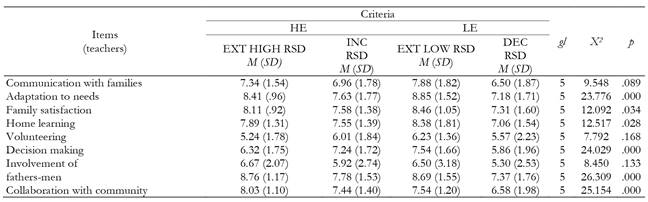

Teaching staff, either from schools with high (HE) or low (LE) effectiveness, differ in overall assessment of the school regarding family-school-community relations (M (SD) = 7.71 (1.35) vs 6.73 (1.90); Z = -3.886; p = .000), the former being more favorable , also in the following two aspects: the school adapts to families´ needs (M (SD) = 7.85 (1.62) vs 7.44 (1.78); Z = -2.025; p = .043); Family participation in decision-making at the school is favored (M (SD) = 6.91 (1.91) vs 6.14 (2.01); Z = -2.842; p = .004). Table 1 below shows evolution in the average score of schools that increase-decrease in residuals (INC RSD and DEC RSD) over the years, as well as those which maintain an extreme high or low residual (EXT HIGH RSD and EXT LOW RSD), from teachers´ perspective.

According to questionnaire data, teachers consider that educational centers with low (Z = -3.370; p = .001) and high (Z = -4.060; p = .000) extreme residuals adapt more to family needs than educational centers of decreased residuals. Families from schools of extreme high residuals are more satisfied than those from schools of decreased residuals (Z = -2.592; p = .010) Teachers from schools of extreme low residuals favor families being more involved in the teaching-learning process at home than those from educational centers of decreased residuals (Z = -2.520; p = .012). Families from schools of extreme low residuals (Z = -2.685; p = .007) and increased residuals (Z = -4.444; p = .000) participate more in decision-making than those from educational centers of decreased residuals. Schools of extreme high residuals collaborate with the community more than those with an increase (Z = -3.738; p = .000) and decrease (Z = -4.134; p = .000) in residuals. Finally, teachers place greater value on the relationship between family-school-community in schools of extreme high residuals (Z = -4.070; p = .000) and increased residuals (Z = -2.680; p = .007 ) than in educational centers of decreased residuals.

Perception of teachers, school management teams and educational inspection

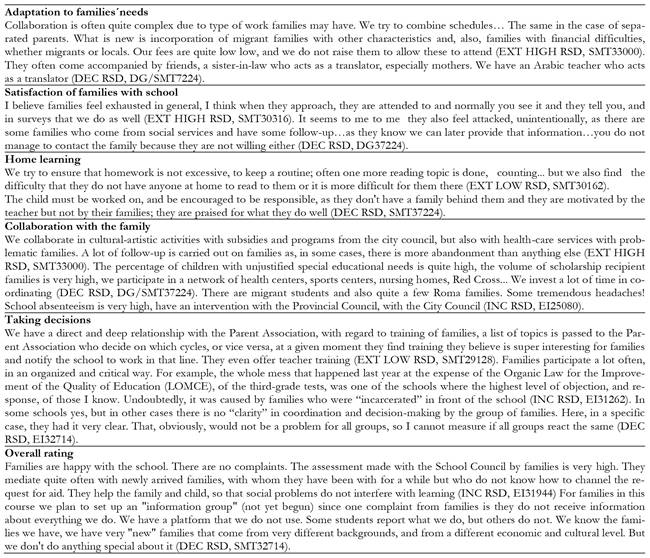

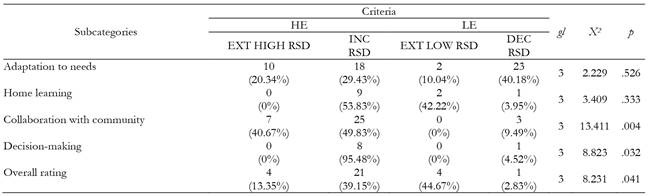

The content of discussion groups with teachers and interviews with school management and inspection was analyzed. Table 2 details coding frequencies, related to the Epstein dimensions, statistically significant in the quantitative study and broken down by school effectiveness criteria.

Table 2. Coding of interviews and discussion groups in subcategories of the general area Family-school-community relations.

As observed, the INC RSD schools provide most references to the different dimensions, except in adaptation to needs that exceed the DEC RSD schools. At the other extreme, the EXT LOW RSD provide least information, compared to the other three groups., The dimension which is most mentioned is adaptation to needs and collaboration with the community, whilst decision-making is least mentioned. Some extracts of each dimension are shown in Table 3.

Comparison between schools of extreme high and low residuals shows relationships with families are priority in the educational project of the EXT HIGH RSD schools, expressed by both school management teams and teaching staff. Their commitment to understanding the needs and demands of families and their attempts to adapt to and satisfy these is manifest in all. However, in information gathered on EXT LOW RSD schools we found hardly any references to family profile. Rather, the desire for greater involvement of these in the school is described, and the fact involvement is not achieved "beyond the usual". As in extreme high residual schools, size and location of the school influence relationships with families.

The contrast between Increase/Decrease Residual schools shows interesting data. Half of INC RSD schools state high family participation in the school, either as they are committed to the Learning Communities project, good availability and time flexibility when receiving families or because families collaborate in extracurricular activities. Nonetheless, the rest of schools state difficulties in persuading families to become involved, though they often stress the importance of welcoming families when they arrive at the school, meeting families of students with difficulties at the beginning of the course; or choosing a parent as class representative. Half of schools refer to the relationship with the Parent Association, although only one specifies its activities. Five schools state training is offered to families, while two mention having had little success in this area as family attendance is quite low. It is noteworthy that these INC RSD schools (with two exceptions) generally mention nothing regarding family diversity; while another states cultural and linguistic difficulties. All schools have a relationship with an institution or community service, mainly with Social Services and the City Council.

Over half of DEC RSD schools actively encourage family involvement. Low SEI and the effect of the financial crisis on families should be considered when justifying results, however. in some schools, though SEI has dropped, this does not prevent a high percentage of ethnic minority families from being integrated. In another school, despite families seemingly having resources, they are actually in situations of financial and family degradation (unemployment, struggling to pay for school canteen, problems buying school material). One public school has a high amount of migrant students and welcomes all who arrive during the course. These families have many survival problems, depend on social services, and lack social integration, have communication problems (language difficulties) and cultural barriers. They have few financial resources and depend on aid.

The presence of fathers and mothers in representative bodies is scarce, if compared to the INC RSD schools, only two refer to participation in the Parent Association (one is a cooperative). Finally, similar to the INC RSD schools, they maintain a relationship with an institution or community service.

Discussion and Conclusions

Firstly, results show primary school teacher assessment of family participation to be mediated by personal factors, thus being a woman is associated with a more favorable assessment of the school's ability to adapt to the needs of families and of their role in the teaching-learning process at home. Those older perceive greater family participation in decision-making, and those with more seniority in the school itself present better overall assessment of the family-school-community relationship. Along these lines, Belmonte et al. (2020) found that female teachers view family participation more positively than their male counterparts and that parental collaboration in the school is better valued by those who are older. Nonetheless, López-Larrosa et al. (2019) found no differences according to years of teaching experience and argue that beliefs about self-efficacy and family-school collaboration have a greater influence.

In addition, teaching staff at high compared to low- effectiveness schools, provide higher global assessment to the school in collaboration, as reported by Azpillaga et al. (2014); they believe the school adapts better to family needs and encourages involvement in decision-making. This highlights the relevance of examining interaction between teaching profile and the importance the school places on collaboration, since it transcends issues concerning educational administration, such as, for example, that related to workforce stability or measures to be implemented or reinforced to promote gender equality.

A more detailed analysis of teachers' questionnaire answers highlights strong contrast between those whose school has had a downward trend (DEC RSD) and the other three groups. As might be expected, schools which function best (EXT HIGH RSD or INC RSD) have a more positive overall assessment of collaboration. It is a priority particularly for the former, with a higher level of adaptation to the needs of families and their satisfaction level. In any case, what they share in common is adopting a school model whose structuring and organization enables a culture of participation (e.g. learning communities, cooperative) and/or they configure a framework of more global and systematic proposals (e.g. within a program or educational project). Simón and Barrios (2019), point out that as regards school improvement, the participation of families is of great value for identification of barriers and facilitators that affect presence, learning and student participation, as well as for planning and implementation processes of initiatives aimed toward school improvement and innovation.

It also highlights that teachers from EXT LOW RSD more than DEC RSD schools try to adapt to family needs and involve them both in learning at home and decision-making, though not always with success. The circumstances of families from these schools (low SEI, economic degradation, high concentration of immigration generally seem to determine that actions taken toward families are often related to welfare rather than pedagogical, and more reactive than proactive, although uncommon, some schools achieve good family integration. However, this may be due to teachers´ negative perception of families at psychosocial risk and these families´ attitudes towards school, which might lead to their estrangement (Armas, 2012) or to the influence of stereotypes on the role played by both teachers and families (Deslandes, 2019).

The attitudes and actions highlighted, throughout interviews and discussion groups, in schools that work best confirm that found by previous studies regarding certain common traits which characterize successful experiences in family involvement (Andrés & Giró, 2016; Consejo Escolar del Estado, 2015; Lewis et al., 2011). All schools try to manage collaboration, in a non-homogeneous way, taking family diversity into account at a structural, cultural, social and economic level (Hernández et al., 2016) however, for this to influence students´ results and school improvement, everything indicates that the key is active effort toward involving families and teachers with more systematic, daily, realistic, flexible and strategically planned actions (Consejo Escolar del Estado, 2015; Deslandes, 2019). Generally, in low- effectiveness schools there is no organized plan focused on previously identified needs or proposals for improvement.

Therefore, knowing the nature of this involvement, not only of those that maintain high levels of school effectiveness-ineffectiveness but also those with an ascending or descending evolution, contributes toward good practices and improvement processes that can be transferable, to a greater or lesser degree, to other schools.

This research shows that over half of schools with favorable evolution (INC RSD) spontaneously allude to training of families, which implies adopting a proactive and non-reactive attitude towards school collaboration. In this regard, it shows the importance of promoting specific training in collaboration, which, according to data from the TALIS 2018 Report (Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional, 2019), is insufficient in Spain and Europe (Thompson et al., 2018 ; Willemse et al., 2018) and especially for school management teams, on whom generation of positive collaborative dynamics depends. Training modalities should be reviewed, to move toward more experiential initiatives (González-Herrera et al., 2017) and with a gender perspective, based on reflection of action, teamwork (Jarauta et al., 2014) and adjusted to the reality of schools with participation of the entire educational community to build a climate of collaboration where each individual is responsible for the educational results of the students and the effectiveness of the school (Rivas & Ugarte, 2014; Silveira, 2016).

One of the most noteworthy contributions of this study is that the consideration of different criteria of school effectiveness, together with the adoption of a quantitative and qualitative research design, has made it possible to examine participatory culture, through the perception of key agents of the educational community (teachers, school management teams and inspection) on family-school-community collaboration and, ultimately, advance in identification and spread of good practices that contribute to school effectiveness and improvement at primary stage.

Among the limitations of this work are difficulties in accessing less effective schools, thus information on these may be scarce and, to a certain extent, hinder dissemination of possible good practices that these perform when collaborating with families and community.

From the psychoeducational viewpoint, research also contributes to outlining lines of improvement that, through interviews and discussion groups, suggest: a) Leaving aside exogenous causes and thinking about how to promote school collaboration; b) Enable teachers to have higher expectations of families and value collaboration; c) Greater training of the educational community to become involved in coexistence projects; d) Involve families in the Observatory for School Coexistence; e) Improve intervention with problematic families; f) Address complaints from families about teaching staff at the school itself; g) Change perceptions of teachers and native families regarding migrants; h) Attend to students in a situation of social vulnerability, making the school a stable reference; i) Strengthen coordination between Parent Association subcommittees; j) Promote Parent Schools; k) Involve fathers ; l) Networking and mediation; m) Promote more confidence among schools in the City Council Schooling Commission; n) Provide resources and conditions to achieve inclusive schooling (and society); and o) Seek new initiatives to bring families closer to and more involved in the school.

The conclusions of other works on initial teacher training and professional development in this area show that not only is it necessary to develop skills for collaborative work with families, but also to focus on cooperation, teacher confidence and cultural sensitivity (Alanko, 2018; Gomila et al., 2018; Mutton et al., 2018); that this be considered an essential component of the school organization and that more attention be focused on the Service-Learning Approach for participation of the family and community (Epstein et al., 2018) and a preventive systemic approach based on values of justice be adopted, social, equity, inclusion and cultural humility (Hannon & O'Donnell, 2021). In this regard, the assessment of communication skills between teachers and families is also advocated (De Coninck et al. 2018), simulation pedagogy to support communication with families (Walker & Legg, 2018) and interprofessional work to foster family-school collaboration (Miller et al. 2018).

This research has focused on the perception of teachers, school management teams and educational inspection, therefore, in future studies it would be advisable to also collect the voices of students and families, particularly minority and culturally diverse families (Miller, 2019; Santiago et al., 2021) to reach a global view of the entire educational community regarding family-school-community collaboration.

texto en

texto en