Introduction

Violence against women is considered a global public health problem according to the World Health Organization, experienced by 1 in 3 women at least once during their lifetime (World Health Organization, 2018). In 2018, it has been estimated globally that 30% of women aged 15-49 have experienced physical and/or sexual violence by an intimate partner, or sexual violence by a third person at some point in their lifetime (WHO, 2018).

In Spain, despite the growing visibility of the phenomenon, the latest Macro-survey on Violence against Women, published by the Ministry of Equality (2019) with women over 16 years of age and resident in our country, has indicated that approximately 34% of the women interviewed suffered some type of violence in their intimate partner relationships throughout their lives. Of the 9,568 women interviewed, 21.7% reported physical, sexual or emotional violence or fear experienced with their partners to the police or in court.

According to this macro-survey, it deserves special mention control violence in the partner, which has reached 38.6% in women in the age range of 18 to 24 years and emotional violence, with a presence of 30.7% in women aged between 25 and 34 years (Ministry of Equality, 2019).

Multiple proposals and efforts have been made to solve this problem in the form of policies for the prevention and elimination of this type of violence, in addition to care and intervention programs for both victims and abusers (Guede et al., 2016). The European Union has responded to this phenomenon with measures such as the EU Victims Directive (2012/29/EU) (Vall-Llovera, 2013) and the Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence (Council of Europe, 2013).

Specifically, in Spain, a multitude of action plans against domestic violence and intimate partner violence have been developed and implemented, as well as important legislative and administrative changes. In this sense, through Organic Law 1/2004, of December 28, 2004, on Comprehensive Protection Measures against Gender Violence, the aim has been to deal with the problem from an integrated and multidisciplinary perspective, focusing on the social and educational spheres, health care for victims, protection of children and adolescents, and the protection of children and adolescents.

The complexity of the explanatory variables of violence against women has aroused special interest in the field of research. Initially, the theoretical models proposed, such as the theories of the aggressor's cycle of violence (Walker, 1979) or the theory of learned helplessness in intimate partner violence (Seligman, 1975), followed a monocausal approach, focusing on factors such as the psychological characteristics of the aggressors and/or victims. This approach has provided interesting data that have contributed to a better understanding of this phenomenon; however, due to the limitations it has presented, multicausal models were proposed.

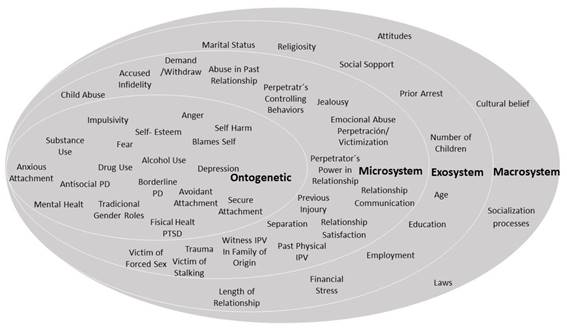

One of the main theoretical frameworks that highlighted the interaction and interrelation of different variables that appear in violence against women was the ecological model developed by Dutton (1985, 1995). This model identifies four levels of this type of aggression: the macrosystem, which refers to all the political, economic and social factors that can influence the pattern of behavior, attitudes, beliefs, the legal system in which the individual develops and performs, and legitimize or justify interpersonal violence; the exosystem, which focuses on social structures, formal and informal institutions that are contexts very close to the aggressors and victims; the microsystem, which includes the environment in which the aggressor acts directly and where the violent behavior occurs, the dynamics of the couple's relationship or family context of origin; and the ontogenetic, which includes the individual characteristics of the aggressor, such as self-esteem or personality characteristics. This type of violence is explained within a continuum, from the macro to the individual, without one level having a higher priority than the other, but rather an interaction between them.

Within the variables studied in the ecological model, multiple studies point out that couple dynamics and the relational and individual variables of the couple play an important role in the process of violence and its evolution (Carbajosa et al., 2017; Gracia et al., 2020; Guerrero-Molina et al., 2017; Hilton & Eke, 2016; Llor-Esteban, et al., 2016; Petersson et al., 2019; Ruiz-Hernández et al., 2015; Shorey et al., 2012; Spencer & Stith, 2020; Stith et al., 2008; Vargas et al., 2017).

Specifically, in relational variables, it has been proposed that men's aggressiveness is directly related to the level of perceived superiority compared to women (Berdahl, 2007; Halper & Ríos, 2019). This could stem from the aggressor's need for empowerment, thus legitimizing hostile/aggressive behavior in daily interactions (Williams et al., 2017). In addition, it has also been observed that the internalization of gender stereotypes seems to influence the description of men and women, and the construction of expectations related to the roles they have to fulfill in the couple relationship. All this affects their self-perception, decision-making, interests, education, coping strategies or conflict resolution, among other aspects (Bian et al., 2017; Ellemers, 2018).

Thus, on the one hand, the identification of sexist beliefs and attitudes would favor the understanding of the mechanisms of functioning and the choice of strategies that aggressors and victims apply in the face of intimate partner conflicts. Likewise, the detection of the cognitive biases underlying these beliefs would play a fundamental role in the intervention with aggressors and victims of intimate partner violence (Echeburúa et al., 2016; Ferrer-Pérez et al., 2019). On the other hand, several studies have pointed out that aggressors present difficulties related to individual variables, specifically in the expression of emotions, cognitive distortions about the woman and the couple relationship, communication deficits, lack of impulse control, substance abuse, personality disorders, pathological jealousy, and depression (Caman et al., 2016; Echeburúa & Amor, 2016; Holtzworth-Munroe & Meehan, 2004; Norlander & Eckhardt, 2005; Parra et al., 2013; Robinat & Justes, 2019; Shorey et al., 2012).

The study of the characteristics of men who abuse their partner or ex-partner comes, on the one hand, from indirect sources of information, such as surveys, the testimonies of victims of violence or professionals who come into contact with them (Buchbinder & Shoukair-Khoury, 2021; Ministry of Equality, 2019) and, on the other hand, from direct information with population convicted of intimate partner violence (Enosh & Buchbinder, 2019; Fernández et al., 2017; Guerrero-Molina et al., 2020; Llor-Esteban et al., 2016; Ruiz-Hernández et al., 2015).

For the purposes of this study, we will focus on relational variables, due to the importance of stereotyped and traditional roles (sexist beliefs and attitudes), and individual variables related to difficulties in the emotional management of aggressors.

The methodology usually used to study the characteristics of intimate partner violence and the aggressors has been mainly quantitative (López & Sandoval, 2016). However, the development of this area of knowledge has required other types of qualitative studies that have complemented and contributed to a better understanding of this complex reality, which is difficult to explore from quantitative studies alone.

Qualitative studies have the advantage of broadening knowledge about the experiences of individuals in daily life, as well as the interpretations and meanings they attribute to the processes in which they are immersed. At the same time, they make it possible to examine the personal and social circumstances in which these events and experiences occur (Braun & Clarke, 2014; Charmaz, 2021).

Thus, the aim of this qualitative study is to explore the perception of those convicted of intimate partner violence about relational dynamics and their coping strategies in conflict situations with their partners, from a relational and ecological perspective. The contribution of their own experiences can be used to understand the mechanisms that influence the appearance of violent behavior, the evolution of conflicts and the strategies used by aggressors to solve disagreements with their partners. At the same time, it is intended to complement this vision with the perspective of professionals who work directly with those convicted of violence against women. Specifically, the specific objectives of the present study are: (a) to study the aggressors' perspective on relational variables at the macrosystem, exosystem, microsystem and ontosystem levels, and (b) to know the professionals' vision of the aggressors in these same areas.

Methods

Design

A qualitative design was used based on the grounded perspective with a constructivist approach (Edmonds & Kennedy, 2017) using focus groups and thematic analysis. This approach was chosen with the aim of gaining detailed knowledge of the triggers involved in the emergence of violent behaviors, the evolution of conflicts in couples and the coping strategies used by the aggressors. The qualitative study of this phenomenon has been previously addressed in the literature (Forster et al., 2017; Sabina et al., 2021; Sabri et al., 2018).

The authors of the present study have extensive experience in health care and research and have published research articles with similar methodology. The focus groups were conducted by the first author, with the occasional collaboration of the other members of the team. She had no previous relationship or contact with the participants. Before the beginning of the sessions, time was dedicated to generating a good rapport, to verbally request informed consent and to remind the objectives of the study. Once the focus group began, a neutral position was maintained so as not to incite any type of specific response. The rest of the authors worked together from the development of the research questions to the dissemination of the results. The main ethical recommendations formulated by the American Psychological Association were always followed (APA, 2016). Authorization was requested from the Ministry of the Interior and the Penitentiary Institution to carry out this research. Regarding the wording, the recommendations of the COREQ guide for focus groups were followed (Tong et al., 2007).

Participants and procedure

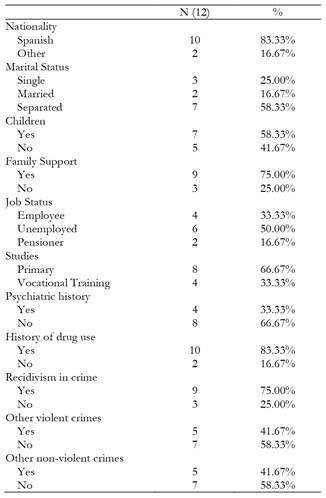

The focus groups were conducted with 16 participants from two different populations from southeastern Spain. The first sample consisted of 12 males, convicted of intimate partner violence and incarcerated in a penitentiary center, selected by purposive sampling. They had a mean age of 36.25 years (SD = 7.68), with a range between 26 and 53 years. Most of the participants were of Spanish nationality (83.33%), with different levels of education, although most had basic education (66.67%). More than half of them were separated and had children (58.33%), and 50% of the participants were unemployed before entering prison. Seventy-five percent were repeat offenders of crimes related to intimate partner violence and 83.33% were drug users. Only 33.33% of these participants had a psychiatric history (more information is available in Table 1).

For the selection of this sample, a verbal invitation was made by one of the authors of the present study, explaining the objective and procedure of this investigation. An informative document and the informed consent form were provided for signature to those who showed interest. The inclusion criteria were: a) being incarcerated in the selected penitentiary center and b) being convicted of intimate partner violence. The exclusion criteria were as follows: a) not giving informed consent to participate in the study, b) not having an adequate level of understanding and expression of Spanish, c) presenting serious psychopathology, and d) having been classified by the penitentiary institution as users at risk of presenting aggressive or disruptive behaviors during the sessions.

The application of this procedure allowed the formation of 4 focus groups. Two sessions were held per group, with an average duration of 1h and 45 minutes. The groups were held in a meeting room within the penitentiary center. The research team had the collaboration of the center's workers, who set up a room for the interviews. At the time of the interviews, only the interviewers and the inmates were present.

Before beginning with the study questions, the objectives of the study were reminded and verbal informed consent was requested again. They were reminded that the conversation would be recorded and transcribed guaranteeing anonymity and confidentiality of the information. Information that could identify the participants in the text document was replaced by numerical codes. Considering the content of the interviews, the professionals of the penitentiary center showed availability to offer the necessary attention to the possible discomfort generated at the end of the interviews.

The second sample consisted of a group of 4 psychology professionals (50% women), with extensive experience in the field of intimate partner violence and belonging to the penitentiary institution. These participants were recruited using the snowball method, after contacting a prison psychologist. All of them were actively working in psychological intervention programs with convicted intimate partner violence offenders, with professional experience of between 10 and 20 years, Spanish and had a mean age of 54 years with ages ranging from 46 to 63 years (SD = 7.58). A focus group was conducted at the home university facilities of the authors, following a method similar to the first sample. All participants gave their signed consent for the recording and transcription of the interviews.

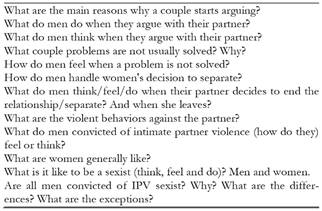

For the focus groups, the recommendations of Krueger (1991) were followed. This methodology proposes conducting group interviews based on a previous script, with general questions about the study objectives, thus facilitating the free expression of the participants. For the elaboration of this script, the authors relied on professional experience, previous bibliography, the elaboration of concept maps and interviews with key informants, concluding in a total of 12 items (see Table 2). This script was tested with a group of inmates not included in this study.

Statistical analysis

For the coding and categorization of the data provided by the focus groups, the thematic analysis proposal of Braun and Clarke (2014) was followed, assuming the realist, constructivist and contextualist perspective. The first approach focuses on the experiences and the meaning that participants construct about the reality they experience. The second, aims to find the influences that social characteristics have had on those experiences, meanings and realities constructed by the participants. The third method captures the way in which individuals make sense of their experiences, while at the same time taking into account how the characteristics of the environment influence these constructed meanings.

Under these three premises, first, the recordings were transcribed by two transcribers (transcriber and reviewer) to, subsequently, make a detailed and repeated reading and familiarization with the information. Subsequently, the information extracts were manually coded using an inductive or bottom-up method (without fitting them into a pre-existing theoretical framework). These codes were organized into groups according to meaning, similarity and emerging patterns through "analyst triangulation" (Patton, 2002), thus forming the different themes.

This process was then repeated by the various coauthors of the present study to refine the topics. Possible discrepancies were resolved by consensus. The themes found were finally assigned to one of the four levels of the predominant theoretical framework for this phenomenon: macrosystem, exosystem, microsystem and ontogenetic.

Results

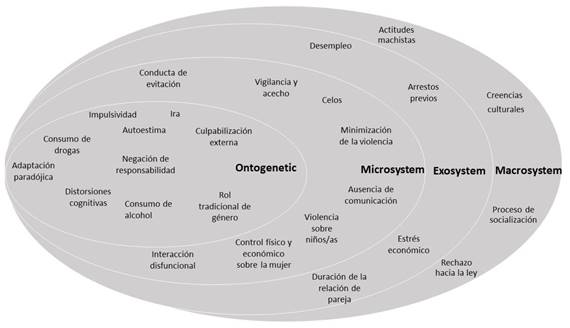

Applying the method described above, descriptors of four categories of Dutton's (1995) nested ecological model were identified and related to the objective of this study: macrosystem, exosystem, microsystem and individual (see Figure 2). First, the results are presented for the group of inmates and, in the second place, for the professionals.

Figure 1. Graphical representation of the Nested Ecological Model, adapted from Dutton, 1995 & Dutton et al., 2005.

Figure 2. Summary of the results obtained, following the Nested Ecological Model, adapted from Dutton, 1995 and Dutton et al., 2005.

Macrosystem in the group of convicted intimate partner violence offenders

The internalization of gender roles and socialization models may determine the expectations related to the behavior of women and men in the couple relationship. The figure of the man who fulfills his role of authority seems to be for the aggressors a cultural premise rooted in the order and social structure of the world. The biased view of sexual roles and male superiority was reflected through the following participant's contribution:

“… another thing is the importance of the purity ring, I’m old-fashioned just like my father, and that’s why if I’m with a woman, I’m with that woman…”;

“… I thought that I could change her and that’s why I definitely kept seeing her,” (Subject 1. 4th focus discussion group).

The change in the legal framework regarding intimate partner violence caused concern and a sense of vulnerability to the new measures among participants:

“… Yes, imagine that, in your life, you go out and, every time you go out to the street, they make up things about you to take away your freedom again. You go out again and they are going to do it again, you go out again and they do it again, how would you get out of that situation? If the law, if the law does not protect you, the law does not support you ...”(Subject 2. 3rd focus discussion group)

They shared the rejection of the Law on Intimate Partner Violence and its inadequate application by the agents of the State Security Corps and the judicial system, generating mistrust.

“…now you know that if the protocol of action catches you in the hands of the National Police, the man will go to jail...”; “it's one thing if you are here because you have assaulted her, you have hit her... but, being here for no reason... it's as if they saw you on the street and said to you: hey, come and get twenty years in jail!...” …” (Subject 3. 1st Focus group discussion)

Participants referred to the cultural ideas and beliefs that influenced the construction of men's and women's identities and the type of relationship they had with their partners. Testimonies were also collected on how political, economic and cultural characteristics impacted on intimate partner violence, as shown in the following example:

“…I had a partner there, in Morocco, but we don't have the same relationship as here in Spain. If you talk, your girlfriend won't talk. We have the right. If you speak, your girlfriend says yes, but here in Spain it is not the same. Where I am from, we have our book, the Quran, and it says the opposite: the woman respects you, you respect her, there, my wife does not go out alone, she does not go to the market alone or to pick up my daughter from school without asking me or telling me. If she doesn't ask me, she doesn't go out, it's not the same as here…” (Subject 2. 1st Focus group discussion).

Exosystem in the group of convicted intimate partner violence offenders

Regarding the risk factors related to the appearance of violence in the couple dynamics, reference was made to the duration of the relationship. The feeling of satisfaction in the dynamics of the couple seems to diminish with the passage of time, due to the deterioration of the degree of cohesion and capacity to express affection, increasing the probability of violence in the couple:

“…No, ...in my case there was no separation at any time, I love my wife...it's been thirty-three years of my life with the same woman and I can't imagine it because I don't think she would propose it to me…” (Subject 3. 1st Focus group discussion)

Reference was also made to the emergence of violence in the couple dynamics as a result of unemployment and loss of purchasing power:

“…but, without money, problems appear and there are discussions, this can't be paid, this can... In my case, for example, we bought a place, a bar by transfer and it was phenomenal... for a year and a half, we earned a lot of money... I spent a lot of money to reform the kitchen and of course, the first problems of paying the bank, of paying other things... we closed the bar and she denounced me the first time…” (Subject 3. 3rd focus discussion group)

The participants discussed how easy it is to get to live different arrests because they needed to continue the affective relationship with the victims, being quite likely the recidivism of the violent behaviors exercised on the victims.

“…I forgave her and kept seeing her... because I loved this girl, but when I didn't do what she wanted, she called the police... in one year, that happened to me twelve times. I have been many times in the dungeon, on New Year's Eve, on my birthday...” (Subject 1. 4th focus discussion group).

Microsystem in the inmate group

The jealousy shown by the aggressors was presented as a need to control and dominate the bond of exclusivity demanded from the partner. The expression of jealousy ranged from situations of distrust to intense discomfort, which could culminate in an explosion of anger. Likewise, the participants expressed constant strategies of imposing criteria and supervision of their wife's behavior.

“… she was going to start working in a bar and I told her: I don't like it, I don't like you working there... get a simpler job, something else... I didn't like that bar because there were many men who would notice her…” (Subject 2. 4th focus discussion group)

In addition, there seems to be a certain need to control women, exercising power over them with various attitudes and behaviors, including economic and physical control or blocking autonomy, among others:

“… And the children, who do they stay with? I have never let my wife work, she didn't need anything ... although she has also told me many times “look, they told me at the town hall that I could work...”, I have told her “you are not going to work anywhere, you are going to take care of your children...”. (Subject 1. 1st Group discussion group).

During couple arguments, they described attempts to control anger with avoidance behaviors, such as leaving the house, identifying this behavior as a coping strategy to avoid escalation in conflicts.

“…Well, I got out of my house, went around the town three times and came back home. When I got back, she was waiting for me and the discussion started again. With the same, without closing the door of the house, I went out again…” (Subject2. 2nd Group discussion group).

The aggressors justify the seriousness of their violent behavior by downplaying the importance of the facts for which they were convicted.

“…I don't know, I don't know... It was during Ramadan and, in Ramadan, you don't eat all day and you get nervous.... It's also what I just said, I was under the pills influence…” (Subject3. 1st Group discussion group).

Another case of legitimization of surveillance and/or stalking behaviors seems to be found when the aggressors felt offended by their partners or perceived threats or hostility from the partner.

“… Man, she has left me for a month or almost two months and went to Morocco. I took my car and went to Morocco, but I didn't tell her I was going to Morocco. I called her on the phone when she was on the boat and I told her: “listen, I'm going to the doctor and I'm leaving my phone at home...” and I was already arriving in Morocco to catch her…”. (Subject 3. 1st Focus group discussion).

The extent of violent behavior is identified with the children of the partners, the convicted persons legitimized violence as a mean to impose discipline and obtain obedience.

“… Me, what I remember most is that her children were very rebellious, I would tell them one thing and instead of doing that thing, they would do something else... And I had a hard time taming them. It is badly said with those words, but it is the truth...that's how it is. On the other hand, with mine (his son), he has pissed his pants... just by doing this... (he makes a gesture with a raised hand). Not them, I have had to spank them to be able to do things…” (Subject 1. 2nd focus group discussion).

Another difficulty in the management of couple conflicts is reflected through a dysfunctional interaction in which they used violence in a bidirectional way. In addition, there was a lack of communication to solve their problems.

“…what happens is that women have been given a lot of power ... if you scold her for something she hasn't done, poof ... one day she slapped me in the street and I slapped her back…” (Subject 1. 1st Focus group discussion).

Individual level in the group of inmates

At the individual level, the aggressors denied their responsibility for the acts for which they were convicted, justifying them with situational explanations and external attribution.

“… this girl was provoking me... we argued one day and a neighbor, who was a civil guard, called his colleagues... and they arrested me. They put a restraining order on me without having touched her and that's why I'm here. It's not for touching her, nor for hitting her... I've never hit a woman…” (Subject 2. 2nd focus group discussion).

They attributed the responsibility for what happened to the partners, their behavior and personal characteristics. In general, they reported that they did not initiate the conflicts.

“… A couple can argue because the woman makes your life impossible. If this happens to you one day, one month, one year... in the end, it drives you crazy and makes your head spin…” (Subject 1. 2nd focus group discussion).

The existence of a paradoxical adaptation of the aggressors to situations of intimate partner violence and its consequences is observed.

“And then comes the bitterness of being alone, you see yourself alone and you see yourself with nothing, you see yourself in the street.... well, not in the street, because you have a family...but you miss them... You miss her and you go back to her...and the same thing happens to you...and that's how we are... you get used to it…” (Subject2. 1st Focus group discussion).

They felt insecure in the face of certain attitudes and behaviors of women:

“she told me: “you are mine and you are going to be mine” ... I pick you up at the gym, I prepare you lunch, even though I was thinking of going home for lunch, she told me that she had prepared lunch at her house. In the end I gave in. I recognize that I am very insecure...very insecure” (Subject 2. 4th focus discussion group).

The interviewees presented difficulty in impulse control and a low level of reflexivity, experiencing an increase in activation, which led to sudden and unexpected episodes of anger and violent behavior.

“… I got a bit carried away by anger too... anger is very bad, it doesn't let you think... even if you are against it and even if it's wrong, there comes a time when you explode and you have nothing to do... that day I didn't go out, I stayed and exploded… (Subject 3. 4th Discussion Group).

The gender stereotypes that men had about women were internalized and influenced the way they related to each other, as well as guided their interpretation of reality, thoughts and actions.

“…women are stronger mentally and can do more damage psychologically... in a high percentage, women are manipulative... you have to do what she wants... they see themselves more protected... and, on top of that, giving them more power, they do what they want with you. They used to do it before... just imagine now…” (Subject 2. 4th focus discussion group).

Finally, substance use seems to have been an avoidance strategy and, at the same time, a risk factor that precipitated the violent reaction in the aggressors:

“… the best thing to do is to go out on the street, go out on the street and get drunk, do drugs because, I must also say that there is some drug use involved…” (Subject 2. 2nd focus group).

Macrosystem in the group of psychology professionals

According to the professionals, cultural aspects and social contexts that promote a differentiated upbringing mark the mental schemes of men and women, and directly influence the expectations and specific roles that aggressors play in the dynamics of a couple.

In this sense, traditional beliefs that promote the perception of male superiority, possession and objectification of women are related to restrictions on women's rights and the existence of male privileges. The professionals found certain cultural differences in aggressors of foreign origin, who have had to assimilate norms and customs different from those of their social environments of origin, for example “when my wife came here, she was spoiled because she encountered your laws and then she thought she could do whatever she wanted” (Professional 4).

The main reason that triggers conflicts is directly related to gender roles. Specifically, with the discrepancy between the mental schema elaborated on the meaning of a couple and the non-fulfillment of one's own expectations in this regard. Thus, Practitioner 1 stresses that these expectations cause the partners to take many situations for granted and comments that: “apparently they believe that the two are on the same line, but they have not put anything in common, they have expectations that the other is in what he believes, that she thinks like him and he is convinced that she follows him” the genesis of the conflict, with the consequent confusion and astonishment of both parties.

The absence of communication and sharing of ideas and beliefs makes it difficult to manage differences. According to Practitioners 2 and 3, those convicted of violence against women in the intimate partner relationship have internalized a fundamental belief: “the man thinks and is certain that the woman has no right to leave, she simply has no right to leave” and this mental scheme is governing their actions without their being aware of it.

Exosystem in the group of psychology professionals

The four professionals shared the appreciation of the low or null awareness of the aggressors about the crime, about the seriousness of their violent behaviors because throughout the dysfunctional dynamics this phenomenon has been normalized: “…they admit that there have been discussions, that there has been WhatsApp messages, they all admit that there has been shouting and threats, but bidirectional, but they consider that “from there to what is written and what I am condemned for, they have gone too far” ...” (Professional 2).

Denial of responsibility makes it difficult to understand the crime. They minimize the consequences of their actions and therefore do not accept judicial decisions or consider them unjust or disproportionate: “He told me that it was not that big of a deal, it was much less than what is stated in the sentence”. They state that “In reality they realize that the behavior they have in a court sentence is not reproachable at all” (Professional 3). A considerable majority negatively assess the intervention of the judicial system, judges and prosecutors, feeling helpless because they were not given the opportunity to contextualize the situation and explain the aggression, expressing their version of the facts.

Microsystem in the group of psychology professionals

Faced with the non-fulfillment of expectations about the partner, aggressors deploy a series of coping mechanisms that are related to the need for control and superiority, speaking of a “code of honor”. According to Professional 2 “When you talk to them about it, none of them is sexist, but they all have a high regard for honor. That is, do not attack my honor, because for my honor I am capable of defending myself... if you are in a status, you really do not receive infidelity, and if you receive infidelity, you fall from the status, your honor disappears”.

In this sense, the professionals agreed that the aggressors feel secure when they exercise economic and social control over the victims, creating mutual emotional dependence and economic dependence on the part of the woman. It is increasingly common to find a dysfunctional dynamic on the part of both partners. Initially, there is bidirectional control, “I give my partner my mobile phone to check it at and she shows me hers” (Professional 4). Subsequently, the aggressor uses jealous attitudes, verbal aggressiveness to justify his violent behavior because they present “a childish behavior, justification, immaturity…” (Professional 2). They consider that the myths of the couple, such as: “the better half, exclusivity, fidelity, being with only one person you are interested in” (Professionals 2 and 4), perpetuate sexist beliefs.

Individual level in the group of professionals in psychology

According to experts, when faced with a conflict situation, it is common for aggressors to feel insecure and show avoidance behaviors: “they keep quiet, they hold on until they explode... or they go to the bar and come back” (Professional 2 and 4). In this way they compensated for the humiliation and feeling of inferiority with impulsive behaviors, such as excessive substance use (alcohol and/or drugs) or anger: “They undoubtedly jump into anger, which can translate into aggressive behavior such as: threats, psychological violence with insults and contempt, belittling, and/or physical violence through pushing, shoving, struggling, hitting, etc.”. Individual characteristics are factors that influenced the management of conflicts in couples, according to Practitioner 2: “…aggressors have a very high level of impulsivity, poor emotional management, and then comes self-esteem... “Why do I feel attacked when faced with an expression? Because I am a function of the results, but if my result is separation, then I am not worth it…”.

Denial and/or minimization of violent behavior in conflict management is common, “even with an injury report and with testimony on the table, and deny and deny and deny…” (Professional 3), a comfortable and self-centered perspective “… a nuance, they do not think more about them, they verbalize more about it, they think about themselves, but they verbalize about it” (Professional 1), ending in general with victim blaming “you don't know how it's made my head spin” (Professional 2), “is the anger they have, “it's her fault, she brought me here”” (Professional 3).

Based on these variables, they construct a reality in which they distort, manipulate and find reasons to maintain the couple's relationship. In the aggressors' discourse, according to Professional 1, it is common to find cognitive distortions and feelings of deception, using the concept of family and the common responsibility with the children to reject the separation and re-empower themselves before their wife “… there may be harassment, harassing behavior, going to see the children at school, following their tracks everywhere, when the separation has been consummated…”.

Through the exercise of authority and dominance, the aggressors establish a family structure in which the asymmetry of power gives them the perception of superiority, being frequent the control of the couple through threats regarding custody, child abuse if the victim denounces, using the children to send messages if the separation has taken place, etc.

Based on the sexist component of love, they legitimize their paternalistic and controlling attitudes, thus justifying women's submission and dependence on the family environment: “… They find it difficult to assume their responsibility as a family, as a father, as a parent, and that is where there is a source of enormous conflict, many do drugs, spend money on addictive leisure activities, do not lead a normalized life of family responsibility with their children and with the family economy. They usually say: these are your children, this is your house, this is your economy and I come and leave you money, and I go party with my friends...” (Professional 2).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore the perceptions of perpetrators about the relational dynamics with their partners and the strategies employed in conflict situations. In addition, these results have been complemented with the perceptions of professionals working in psychotherapeutic intervention with aggressors.

Our results show differences among the participants in terms of their awareness of violence against their partners, the characteristics of each individual, the circumstances of each family, and the particularities of each culture and/or subculture. This finding is congruent with previous studies that have pointed out the existence of differential profiles among different groups of batterers (Fowler & Westen, 2011; Holtzworth et al., 1994; Llor-Esteban et al., 2016), with significant differences in variables such as age, level of education, economic and labor activity and other contextual variables (Herrero et al., 2016; Vargas et al., 2017).

Specifically, we have been able to identify response strategies on the part of those convicted of violence against women such as minimization and/or denial of the violence, avoidance of confrontation, poor communication, pathological jealousy or fear of separating from their partners. Along these lines, our results coincide with those shown by previous studies on the type of relationship built by aggressors and its evolution (Boira et al., 2013) and on certain profiles depending on the violence employed and individual characteristics (Holtzworth et al., 2004).

At the macrosystem level, our analyses show that aggressors have a very differentiated view of male and female roles, learning and internalizing beliefs and attitudes that seem to promote a stereotypical view of the behavior of women and men. These cultural ideas and beliefs have been reflected in the socialization models they have followed in the formation and development of their own relationships and are related to the perpetuation of intimate partner violence.

Several studies indicate that sexist attitudes, hostile attitudes towards women and traditional beliefs are related to intimate partner violence (Abbas et al., 2020; Boira et al., 2014; Guerrero-Molina et al., 2017; Guerrero-Molina et al., 2021; Juarros Basterretxea et al., 2018). This type of learning and socialization is contrary to the construction of couple relationships based on gender equality that is currently promoted. Faced with this new reality, aggressors find it very difficult to adapt because their beliefs are different and they live their masculinity with some confusion (Ferrer-Pérez & Bosch- Fiol, 2016).

The findings of our study at the exosystem level indicate that the aggressors have perceived institutional treatment differentiating between women and men, perceiving themselves in a situation of helplessness or powerlessness, coinciding with those of the study by Boira et al. (2013). The group of aggressors negatively assessed the judicial system and social support, expressing their discomfort with the procedure once accused of the crime of abuse and the little help they have been given.

At the same time, professionals have emphasized that the legal system does not discriminate between different cases of abuse with respect to the nature, development or consequences, having an important influence on the aggressors' assumption of responsibility and adherence to treatment. In addition, professionals point out that this can reinforce irrational beliefs about violence and expectations of changing the strategies used by batterers to resolve conflict situations during the relationship.

Regarding the social support system in formal and informal systems, our results coincide with the study conducted by Vargas et al. (2017) in which respondents have perceived, in general, less social support. Finally, at this level, it has been observed that the presence of cognitive distortions implies the consideration of women as inferior and vulnerable. This could contribute to an increased risk in the recidivism of violent behaviors with partners (Arce et al., 2014; Guerrero-Molina et al., 2020). According to our results, professionals consider that aggressors do not accept the decisions of their partners, trying to think for them and convince them of the reality that they believe.

At the microsystem level, the results identify difficulties in emotional management, low levels of self-control and difficulties in recognizing negative emotions. The aggressors express astonishment and concern for the couple's relationship, for the children in common, and feel fear and mistrust at the possibility of starting a new relationship with their partner.

The professionals consider that the aggressors have a rigid mental schema that is directing their actions, although they are not aware of it, possibly because they have not reflected on the real reasons for the conflict or have not asked themselves questions about it. In the context of the couple's relationship, the presence of jealousy, bidirectional violence, loss of marital satisfaction, ideas about the legitimization of bullying behaviors, power asymmetry and exercise of control over partners are described. Other previous studies have shown the existence of this group of variables in similar samples (Guerrero-Molina et al., 2017; Sabri et al., 2018; Spencer et al., 2019; Stith et al., 2004; Stith et al., 2008).

According to our results, the use of dysfunctional conflict resolution strategies, such as avoidance of verbal confrontation and ineffective communication to reach agreements, make aggressors feel threatened by the superiority of their partners, employ violent behaviors that they later minimize or deny, externalize responsibility for their aggressive acts, and blame the victim (Barreira & Jiménez, 2020; Echeburúa & Muñoz, 2017).

One of the main strengths of this study is the appearance in the results of testimonies related to the instrumentalization of children in intimate partner violence from the perspective of the aggressors. Most of the studies on the impact of intimate partner violence on children have been carried out from the contributions of the women victims or through surveys. In general terms, we have observed that violence against women extends to children due to the deficit of conflict resolution skills in couples and the impossibility of meeting the demands and needs of parenting and education. These findings are congruent with research conducted by Callaghan et al. (2015), Cater & Sjogren (2016), and Miranda et al. (2021), who report the generalization of aggressive behavior in mothers towards their children.

At the individual level, it is observed that internalized sexist attitudes and beliefs may be influencing the interpretation of reality, the presence of cognitive distortions and stereotyped ideas about women. Other studies have found evidence of the presence of cognitive biases in male batterers, consistent with our results, and very useful in the psychotherapeutic process (Echeburúa et. al 2016; Ferrer-Pérez et al., 2019; Loinaz, 2014).

The assessment of the professionals participating in the present study indicates that any situation that does not conform to the rigid structures of thought triggers actions in the aggressors with the aim of feeling empowered and superior to their partners. We consider that the use of strategies of minimization and/or denial of violence against their partner can be related to a defensive attitude towards the facts, with the level of insecurity and low tolerance to frustration shown by the aggressors, in accordance with the results found in the studies carried out by Barreira & Jiménez (2020), Guerrero-Molina et al. (2020) and Stith et al. (2008). Together with poor communication skills, subjects describe increased activation and an inability to reason and react with impulsivity, which can be exacerbated by substance use. These risk factors are in line with the findings of other studies (Echeburúa & Amor, 2016; Juarros Basterretxea et al., 2018; Spencer et al., 2019; Stith et al., 2004).

Regarding awareness of abuse in relational interaction, the results indicate that it is a long process and that it may not be achieved until participation in psychological intervention, as a consequence of a conviction for intimate partner violence. A line of research carried out in a cognitive behavioral treatment program for violent men has highlighted the existence of psychological problems, substance abuse, emotional instability, situations of abuse in the context of origin and personality disorders (Echeburúa et al., 2009; Llor-Esteban et al., 2016).

Another of the main strengths of the present study are the results concerning the paradoxical adaptation of the aggressors to situations of intimate partner violence, little evidenced to date. The aggressors remain in the same dysfunctional couple dynamic and with harmful consequences for themselves, most of the time facing judicial proceedings, convictions and implementation of precautionary measures or custodial sentences. This is a different phenomenon from recidivism, which has been widely studied (Echeburúa et al., 2016; Guerrero-Molina et al., 2020; Pérez & Fiol, 2016) and which indicates that repeat offenders in intimate partner violence present a greater number of cognitive distortions with respect to women. This aspect contradicts the need for control and superiority that aggressors show in their relationships, since after being denounced several times and suffering the consequences of these, they return with the same partners, so that deficit strategies and conflicts become cyclical.

Conclusions

This study allows us to qualitatively explore the dynamics and coping strategies used by those convicted of intimate partner violence in their intimate relationships.

At the macrosystem level, the internalization of gender roles and maladaptive socialization models, the perception they have of the legal framework and the rejection of the law on Intimate Partner Violence and the cultural beliefs and ideas about the couple relationship are observed. At the exosystem level, violence against women is associated with the deterioration of cohesion and capacity to express affection in long-term couples, violence derived from work or economic problems, and multiple arrests suffered when trying to maintain contact with the victims.

At the microsystem level, there is evidence of jealousy, need for control, avoidance behaviors in the face of new aggressions, minimization of violent behaviors, legitimization of intimidation or stalking behaviors, extension of aggression to the children in common, and dysfunctional interaction due to communication problems. At the individual level, there is denial of responsibility, attribution of guilt to the victim, paradoxical adaptation, insecurity in the face of women who pose a threat to self-image, deficit of impulse control, internalization of stereotypes and substance abuse.

In addition, this vision has been complemented by the perception of psychology professionals working in prisons. In this sense, at the macrosystem level, testimonies appear that reflect the traditional beliefs of male superiority, possession and objectification of women, the influence of gender roles and the absence of communication based on the internalization of stereotypes. At the exosystem level, there was low or no awareness of crime and its seriousness, as well as a lack of responsibility for crime.

At the microsystem level, the testimonies show coping mechanisms related to the need for control and superiority at the social and economic level while, at the individual level, reference is made to insecurity, avoidance, substance abuse, denial or minimization of violence, distortion or manipulation of reality, and legitimization of sexist attitudes.

This work makes interesting contributions for research professionals and for those who work in intervention and/or prevention in intimate partner violence. The combined vision of aggressors and professionals has rarely been studied, so new evidence and information aimed at achieving an integrated view of the dynamics and skills mentioned above are provided.

In addition, in our thematic analysis we obtained two blocks of information that are unusual in the literature. On the one hand, that referring to the instrumentalization of children from the perspective of the aggressors, where the extracts from the interviews revealed the extension of violence against women towards their children. Possibly these behaviors derive both from a deficit of skills in conflict resolution in couples, as well as from the impossibility of complying with the demands of the educational process. On the other hand, the paradoxical adaptation of the aggressors to situations of intimate partner violence. In this sense, it is noted that dysfunctional dynamics with partners are maintained, although the consequences at the judicial level may be significant.

Limitations

The present study has some of the limitations commonly reported in qualitative designs. The use of an incidental sample from one region (professionals) and one center (offenders) cannot be considered representative of the population of offenders in the locality or the country. This implies that global inferences are very limited.

The influence of culture and context makes it necessary to develop studies that explore possible cross-cultural variations and similarities in attitudes. Despite this, comparison with the literature suggests that it is possible that some of the results observed may also appear in other populations.

As recommendations, the authors propose qualitative studies that obtain larger samples for both groups and, if possible, introduce the testimony of the victims. It would also be interesting to propose longitudinal research designs of a quantitative nature, which would allow us to gain in-depth knowledge of the relationship between the variables presented here.

texto em

texto em