Introduction

Erikson (1968) called the stage of adolescence a "psycho-social moratorium", a stage of waiting that society grants adolescents to search for their identity. In these first formulations, Erikson already indicated that there were certain groups of people who had the possibility of extending this moratorium period (for example, university students or people with high social status) and that, therefore, in these cases, the achievement of identity would occur during the third decade of life (Erikson, 1968). While in the mid-20th century the percentage of young people who could extend the moratorium was not very high, currently and as a consequence of the social and economic changes associated with the technological revolution, the increase in this moratorium is characteristic of young people, at least in developed countries. This fact was pointed out by Arnett (2000, 2015), coining the term Emerging Adulthood, a term that refers to the vital period between 18 and 29 years of age and which he defined, among other issues, as an unstable stage with great possibilities, in which people are focused on themselves, feeling that they are not yet adults although they are no longer adolescents and who continue to explore and search for their identity. These same characteristics have also been found among young Spanish people (Sánchez-Queija et al., 2020). In the Spanish context, it has also been found that, among the different identity contents, concern for the future -perhaps the most representative content of the search for identity- stands out in emerging adulthood compared to other vital stages (Gifre et al. , 2011). These data show the importance of studying the development of identity at this stage of the life cycle, particularly in Spain.

Identity is represented, according to Erikson (1968), along a continuum in which identity synthesis (knowing who one is and what roles one wants to play in society) is found at one pole and at the other, confusion (not knowing clearly neither who one is nor what roles to play). In the first case, it is a reworking of childhood identity into a more complex one, while in the second case, it refers to an inability to develop an adult identity. James Marcia operationalized this definition and built a typology of identity status based on two dimensions: exploration and strength of commitment (Marcia, 1966). Exploration is defined as a problem-solving behavior, a search for relevant information about oneself in decision-making in life, evaluating the different possible alternatives in order to identify with certain roles, ideas or professions (Grotevant, 1987). On the other hand, the strength of commitment represents the adherence to certain values, beliefs and goals (Marcia, 1988). Dividing the levels of exploration and strength of commitment into high and low, and juxtaposing each level of one with the level of the other, Marcia created four independent identity statuses (Marcia, 1966; Tesouro et al., 2013): identity achievement (strength of commitment after exploration), moratorium (exploration without having committed yet), foreclosure (strength of commitment without previous exploration) and identity diffusion (absence of both, strength of commitment and exploration).

The identity status theory is still valid and continues to be the framework for the study of the development of personal identity, although it has had some subsequent developments. Among them, Berzonsky's model of identity styles (1990) stands out. This author postulated that there are different ways of carrying out the exploration proposed by Marcia, ways that define three different styles of identity. Thus, while the identity statuses proposed by Marcia are based on actions in the past (the person has explored or not, has committed or not), the styles postulated by Berzonsky focus on the method with which we deal with daily life situations and with which the strength of identity commitment is sought (Berzonsky et al., 2013). The three styles proposed by Berzonsky (1989, 2004) are: informational, normative and diffusive-avoidant, and they are usually analyzed together with strength of commitment to find out how the strength of commitment and the three forms of exploratory behavior interact in the formation of the identity (Szabo et al., 2016).

People with an informational identity-seeking style appropriate information, engage in problem-focused coping, and actively explore. These people achieve a flexible commitment. People who use a normative style use imitation and conformity to the norms of a given reference group. The normative style is associated with a closed, rigid, and dogmatic view of commitment, as well as the suppression of exploration. Finally, people who use the diffusive-avoidant style tend to avoid actively seeking identity, generally paying little attention to the future and their long-term choices and using an emotion-focused coping. This style is associated with low levels of strength of commitment (Berzonsky 1989, Berzonsky et al., 2013, Schwartz et al., 2015; Skhirtladze, 2016).

Regarding age, empirical research shows that as age increases through the 20s, the percentage of people with achievement status will increase and the percentage of people with diffusive status will decrease (Berzonsky, 2008). Likewise, the informational style is expected to increase with age while the normative style should decrease (Luyckx et al., 2013).

In addition to age, previous studies have studied the differences in both, the status and the identity styles based on sex. If the search for and resolution of identity is an evolutionary task marked by the socio-historical context in which one lives (Cieciuch & Topolweska, 2017; Erikson, 1968), it makes sense that the different ways of treating sexes by society are reflected in differentiated identity styles. Some previous results indicate that men show higher scores in the diffusive-avoidant style than women and, consistently, women present a stronger achievement status or identity strength of commitment than men (Berzonsky, 1992, 2008; Crocetti et al., 2014; Lewis, 2003).

Consistent with Erikson's theory, a coherent sense of identity (or achievement identity in Marcia's terms) is essential to enable people to effectively adapt and overcome the adversities of everyday life. In this line, some research has shown that the styles that facilitate the adoption of strength of commitment, that is, the informational and normative styles, positively correlate with aspects such as self-esteem and well-being (Karaś et al., 2015) or with agency (Berzonsky & Kuk, 2021), while the style that makes it difficult to acquire commitments, the diffusive-avoidant style, appears as the most maladaptive, being negatively associated with indicators of well-being (self-esteem, optimism) and positively associated with markers of distress: depression, stress, anxiety, with the intake of alcohol and other drugs, delinquency and illegal behaviors (Berzonsky & Kuk, 2021, Schwartz, 2013; Karaś et al., 2015; Schwartz et al. 2015; Schwartz et al., 2017). These results have been found across different samples, such as American, which is where the bulk of the research on identity styles has been carried out, or Italian, Polish and Romanian (Karaś et al., 2015).

However, these data are not always replicated and, for example, Vleioras and Bosma (2005), with a Greek sample, found no relationship between informative and normative styles and the different dimensions of well-being; Shwartz et al. found, with an American sample, that while the informational style is associated with dimensions that reflect development, autonomy, acceptance, and growth, the normative style is positively related to acceptance, but negatively related to personal growth and autonomy (Schwartz et al, 2013); Finally, it has been found with Canadian and American samples, that only the normative style was related to better self-esteem and self-concept (Johnson & Nozick, 2011) or with fewer depressive symptoms and loneliness (Berzonsky & Kuk, 2021), whereas the informational style did not.

Berzonsky and Cieciuch (2016) pointed out that these differences could be explained because not all the studies controlled for the role of strength of commitment in the relationship between identity styles and well-being/distress, when this strength has consistently been shown to favor well-being and protect against distress (Skhirtladze et al, 2016). Thus, in their work, they showed that the relationship between identity styles and aspects of well-being were mediated by levels of strength of commitment (Berzonsky & Cieciuch, 2016).

Identity is defined as a psychosocial construct (Erikson, 1968), as the person does not build their identity alone, but rather does so within a specific historical-cultural context. Previous research shows that the relationship between identity and well-being/distress changes depending on the culture of origin (Crocetti et al., 2015; Suh, 2002). For this reason, it is important to continue to study the construction of identity and its relationship with well-being/distress across different cultures. As far as we know, this is the first research carried out in Spain that analyzes the relationship between identity and psychological well-being/distress, during emerging adulthood, which is a stage that has not yet been studied in the Spanish context and that is so important for development in general and for identity development in particular. Moreover, it does so using Berzonsky's theoretical framework of identity styles, a theoretical framework that has not been explored in our context either. The present study has three objectives. First, to describe the differences based on age and sex in the use of the different identity styles of a sample of Spanish emerging adults. Second, to analyze the relationship that exists between the different identity styles and the variables of psychological well-being and distress. Third, to know whether the achievement of a strength of commitment mediates the relationship between identity styles and psychological well-being and distress. These three objectives will allow us to know not only how these variables are related, but also whether the previous research carried out mainly within Anglo-Saxon contexts is replicated or not in a southern European country.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 278 emerging adults (70.9% girls), aged between 18 and 29 years (M = 22.03; SD = 2.65). Of the total sample, 65.6% lived in urban areas (province capital or municipality with more than 25,000 inhabitants). Regarding the perceived socioeconomic level of the participants, 31.8 % reported having a low level, 42 % a medium level, and 26.1 % perceived themselves to have a medium-high socioeconomic level. On the other hand, 70.5 % lived in their home of origin, 25.9% lived in a shared house or residence and 3.6 % had become independent. Regarding the level of studies, 7.2 % had completed their primary or secondary studies, 64.7 % had finished high school or professional training and 28.1 % had completed their university studies. Lastly, the employment situation was as follows: 44.2 % were not working or looking for a job, 32% were not working but were looking for a job, and finally, 23.7 % had a part-time or full-time job.

Instruments

A sociodemographic questionnaire was prepared where the participants indicated their sex, age, place of residence, educational level, employment situation, with whom they lived with and the perceived level of income of the family unit.

The participants also answered the following instruments:

Identity scale (Identity Style Inventory, ISI-5,Berzonsky et al., 2013). The Spanish translation of the ISI-5 scale was used, which is composed of 36 items evaluated on a Likert-type scale from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree). These items measure four dimensions: informational style, composed of 9 items (α = .75, e.g. “When I am faced with an important decision in my life, I try to analyze the situation in order to understand it”). Normative style, composed of 9 items (α = .69, e.g., “I never ask myself what I want to do with my life because I tend to do what the people I care about expect me to do”). Diffusive-avoidant style, composed of another 9 items (α = .72 eg “When I have to make an important decision in my life, I try to wait as long as possible to see what happens”). And finally, the strength of commitment, with 9 items (α = .71 e.g., "I am clear about my goals in life").

Psychological distress. It was evaluated through the Spanish adaptation (Bados et al., 2005) of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales, DASS-21 (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). It is a 21-item questionnaire on a Likert-type scale from 1 (not at all applicable to me) to 4 (very applicable to me or applicable most of the time) that is composed of three subscales: depression (α = .84 e.g., “I have not been able to feel any positive emotions”), anxiety (α = .83, e.g., “I felt that I was on the verge of panic”) and stress (α = .81 e.g., “It was difficult to relax"), grouped into a second-order factor: general psychological distress (α = .92).

Well-being. Two instruments were used. First, the Spanish validation (De la Fuente et al., 2017) of the Flourishing Scale (Diener et al., 2010), composed of 8 items on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) that evaluates the flourishing dimension (α = .80). An example of an item would be “I lead a life with meaning and purpose”. High scores represent a person with psychological strength and resources. Second, the Spanish validation (Rivera, 2015) of the Optimism scale (Scheier, Carver, & Bridges, 1994) was used. It is a 10-item questionnaire on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree) that measures a single dimension (α = .68, eg, “In difficult times, I usually hope for the best”) .

Procedure

The data were collected through a questionnaire that was distributed between January and February 2015. The booklet was filled out on paper, taking the respondents an average of 30 minutes to fill it out. Participation was voluntary, and it was carried out through non-probabilistic snowball sampling (Branjerdporn et al., 2019). Thus, one of the great problems of research in emerging adulthood was avoided: that the samples are usually composed exclusively of university students. All participants were informed of the purpose of the study in writing and assured that the survey was both anonymous and confidential. The inclusion criterion was to be aged between 18 and 29 years at the time of data collection. The study was approved by the Andalusian Biomedical Research Ethics Committee.

Data Analyses

The IBM SPSS Statistics program, version 19, was used. First, a descriptive analysis and a comparison of means were performed for the identity variables (informational, normative, diffusive-avoidant styles, and strength of commitment), flourishing, optimism, and psychological distress (depression, anxiety and stress) according to sex.

The effect size was analyzed using Cohen's d (1988), considering d = .20, .50, .80 as low, medium, and high effect size respectively. The second step was to carry out correlation analyses, first between identity styles and age and, later, between identity styles, strength of commitment, flourishing and psychological distress. Finally, analyses were carried out to evaluate whether there was a mediation of the strength of the commitment between identity styles and well-being/distress. To do this, simple regression equations were performed between identity processing styles and commitment strength, on the one hand, and, on the other, multiple regression equations between identity processing styles and commitment strength as IV (independent variable) and well-being/distress variables as DV (dependent variables). In addition, the statistical significance of the mediation was calculated through the Sobel test using the program developed by Jose (2013).

Results

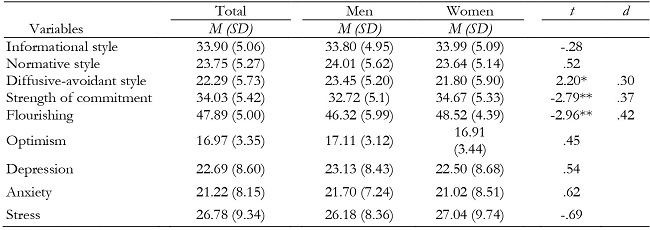

As we can see in Table 1, the differences between the men and women in this study's sample are not significant in the variables related to optimism or distress, nor in the informational and normative styles. But there are differences in flourishing, strength of commitment and diffusive-avoidant style. Thus, it is observed that women scored higher in flourishing and in strength of commitment while men scored higher in the diffusive-avoidant style. The t statistic was used for equal variances, except when Levene's test indicated that different variances existed (for example, in flourishing).

Table 1. Descriptive (mean, standard deviation) and comparison of means between men and women in the variables related to identity, flourishing, optimism and depression, anxiety and stress.

*p < .05;

**p < .01

Regarding the age variable, a Pearson correlation was carried out between age and the rest of the variables analyzed. There was only a residual correlation with the normative style (r = -.11, p = .07), which indicates that the older the person, less use of the normative style. There was no correlation with the rest of the variables studied.

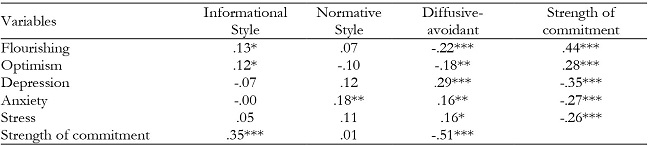

Table 2 shows the correlations between the variables referring to the styles of coping with identity and the well-being and distress variables analyzed. A small, positive correlation was found between the informational style and the variables of flourishing and optimism, as well as a medium positive correlation with the variable strength of commitment. On the other hand, the normative style correlated positively with the anxiety variable. The diffusive-avoidant style correlates positively with depression, anxiety, and stress, and negatively with flourishing, optimism, and strength of commitment. Finally, the greater the strength of the commitment, the more flourishing and optimism and the less depression, anxiety and stress were found.

Table 2: Correlation styles of identity, strength of commitment, flourishing, optimism and general distress.

Note.*p < .05;

**p <.01;

***p < .001

Table 2 also offers noteworthy information: the strength of the commitment correlated positively and with a medium size with the informational style, it had a correlation close to zero with the normative style and a negative correlation of medium size with the diffusive-avoidant style.

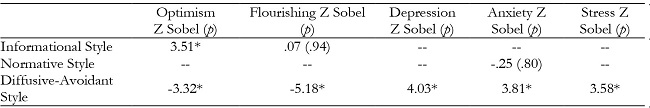

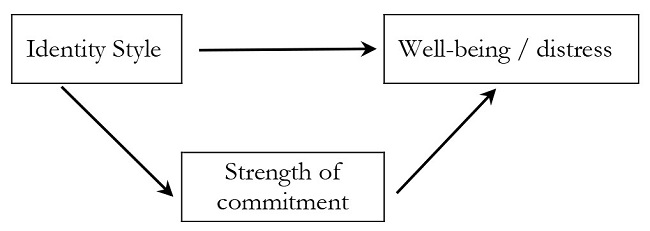

Lastly, we tested whether the strength of the commitment mediated the relationship between identity styles and the well-being and distress variables evaluated (see Figure 1). Table 3 shows Sobel's Z statistic, indicating which of these relationships were significant.

Figure 1. Theoretical model of mediation between the three identity styles and the variables of psychological well-being/distress.

The results show that there was a total mediation of the strength of commitment between the informational style and both optimism and flourishing. In this way, the relationship between the informational style and the optimism and flourishing variables disappeared when the mediation of strength of commitment was included. Those people who use this style are more committed and it is this strength of commitment that is positively related to both DVs.

On the other hand, the strength of commitment completely mediated the relationship between the diffusive-avoidant style and anxiety and stress, while it only partially mediated depression. In the latter case, the relationship between diffusive-avoidant style and depression became weaker when the strength of commitment was included in the model, as part of this relationship is due to the fact that the diffusive-avoidant style implies less strength of commitment, and this is negatively related to depression.

Discussion

The objectives of this work were to describe the differences in the use of identity styles based on age and sex, to analyze the relationship between these identity styles and the strength of commitment with the variables of well-being and psychological distress and, finally, to know whether the commitment mediates between the identity styles and psychological well-being and distress.

The results indicated that men were less committed than women and, consistently used a diffusive-avoidant style more than women. These data are consistent with previous research (Berzonsky, 1992, 2008), which suggest that these differences are due to the fact that socialization is different according to sex, men tend to have more freedom and less supervision and, therefore, the achievement of identity would occur later (Berzonsky, 2008). On the contrary, women put their maturity to the test earlier, making decisions and taking on responsibilities during adolescence (Schultz et al., 2003) so that by the time they enter into emerging adulthood they would have greater strength of commitment than men.

On the other hand, in relation to the changes with respect to age, in this study, we have only found a residual relationship between age and normative style, so that older participants use the normative style less. This result is, in part, counterintuitive, since as age increases, it is expected that the levels of achievement state (related to the informative style) would increase and the diffusive state (related to the diffusive-avoidant style) would decrease (Luyckx et al. al., 2013). However, these results have not been found in this sample.

Especially striking is the absence of a correlation between the strength of commitment and age. This absence may simply be due to the sample, as 74.1 % of emerging adults were under 23 years of age. But it may also be due to the very definition of the stage of emerging adulthood and the specific characteristics of the Spanish context. Emerging adulthood is a stage of identity search, feeling in no man's land and not knowing exactly what roles and commitments to adopt (Arnett, 2000, 2013; Arnett & Tanner, 2016). Spain is, perhaps, one of the contexts in which the conceptualization of emerging adulthood best fits: the unemployment rate among young people reaches 40.5%, they leave the family home with an average age of 29.4 years and the first child arrives around the age of 30.4 years (INE, 2018). In this context, it is difficult to adopt typical adult roles, as the lack of economic and residential independence and the inability to form a family of their own makes it very difficult. Identity is a psychosocial construct, and it is difficult to commit in a society that offers an uncertain future and when there is still time to have the option of adopting adult roles. Or perhaps, as Bauman (2007) pointed out, more than a clear commitment, young people acquire multiple partial identifications that allow them to adapt to constant change. In the face of so much transformation, it is best not to commit to anything. In the words of the aforementioned author: "Today, commitments tend to be very frowned upon, unless they contain an until further notice clause" (Bauman, 2007, p. 31). Bauman and Arnett agree that the social transformations of the last 30 years have led to a different development of the Life Cycle. According to the sociologist Bauman, in the 21st century society, political, work or partner commitments are superficial and are defined in the short term, in a vision of the person as always in a state of transience and who navigates in a sea of uncertainties (Bauman, 2003). For his part, the psychologist Arnett limits the state of transience or instability to the period of emerging adulthood. For Arnett, emerging adulthood is the time to seek and establish commitments, fundamentally in the workplace and as a couple, commitments that the emerging adult person will end up achieving, as current research shows (for example, Luyckx et al., 2013). In any case, we are faced with the challenge that institutions such as education may provide tools and strategies to learn to live in this new world and include in their curriculum strategies to get to know oneself personally, which will help to consolidate identity, taking into account that the data show an important relationship between the strength of commitment and high psychological well-being and low psychological distress.

Regarding the relationship between identity styles and indicators of well-being/distress, we can see that adopting an informational style is shown to be a protective factor as it has positive correlations with well-being. However, the absence of informational style is not a risk factor, as it is not related to distress. The mediation analysis shows that the relationship between informational style and optimism and flourishing is due to the fact that it is easier to establish a strong strength of commitment when using this style. Thus, a consolidated, personal and self-developed identity, which has already been shown to be related to well-being indicators such as autonomy, self-esteem and satisfaction with life (Schwartz, 2013) is also related to flourishing and optimism.

Adopting a normative style has been related to anxiety, something that can be explained by having adopted an identity foreign to the individual, borrowing an external identity. This would imply resistance to changes and avoidance of information that does not fit the standards of the person who uses the normative style (Schwartz, 2001), causing distress. Or perhaps the opposite may occur, when it is the most anxious people who seek a normative identity in order to reduce their anxiety levels. It is noteworthy that, contrary to previous results (Berzonsky, 2003), we found an absence of correlation between this style and the strength of commitment, which is, ultimately, and as we are seeing in the other two styles, the variable which is more strongly related to well-being and distress.

On the other hand, the diffusive-avoidant style not only includes a positive relationship with indicators of distress, but its relationship is inverse with those of well-being. That is, it is a risk factor for the personal adjustment of emerging adults. Again, the mediation analysis explains the mechanism by which this relationship occurs. This fact may be due to the low levels of strength of commitment that people who use this style acquire, as has been shown again in this sample, and it would be these low levels, which have already been related to low self-esteem and unstable self-concept (Berzonsky, 2013) or with depressive symptoms and loneliness (Berzonsky & Kuk, 2021), that would explain the distress caused by the diffusive-avoidant style.

Finally, it is worth noting that our study has some limitations. First, it is a reduced sample obtained using snowball sampling method. Although this method is a common strategy to access hard-to-reach groups, known in the literature as hard-to-reach populations (Atkinson & Flint 2001), which has allowed us to reach non-university emerging adults, it also carries some risks, such as the difficulty in extrapolating the data to the general population due to the possible over or under-representation of certain groups that can give rise to sample representativeness problems (Atkinson & Flint 2001). Second, the exclusive use of questionnaires without collecting qualitative information that allows us to understand what arguments and strategies the participants contribute to the study is also a limitation that could be dealt with in future lines of research. Third, the results may have been affected by the imbalance of the sample based on sex. However, despite the small sample used, this sample avoids the main handicap of previous studies with emerging adults: the fact that they are usually carried out with university students. In addition, the results coincide with those of other previous studies (e.g., Berzonsky & Cieciuch, 2016), which provides great external validity to the present study, allowing the information found to be generalized to the Spanish population. It is important not to forget the importance of the context in the search for identity, identity that is ultimately and, as we have already mentioned, a psychosocial construct. Developmental psychology cannot continue to study the psyche without taking into account the context in which the organism develops (Overton, 2015). Thus, this is, as far as we know, the first research carried out in our country that uses Berzonsky's identity styles, a long line of research in other countries. From the present study we can deduce the importance of the strength of commitment in personal well-being and, therefore, the need for the different social agents to provide public policies that favor the development of the identity of our young people who are the most educated generation of our history and, therefore, a necessary bet.

texto em

texto em