My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

The European Journal of Psychiatry

Print version ISSN 0213-6163

Eur. J. Psychiat. vol.19 n.2 Zaragoza Apr./Jun. 2005

Frequency and characteristics of emotional disorders in patients after ischemic stroke

| D. Kadojić Department of Neurology, University Hospital Osijek, Croatia |

Key words: Depression, Anxiety, Emotional disorder, Stroke.

ABSTRACT - Emotional disturbances in stroke patients may unfavorably affect the process of rehabilitation and longterm outcome of the disease. The aim of the study was to assess the prevalence of emotional disturbances and their characteristics in our stroke patients, according to hemispheric lateralization of cerebral lesion (as recorded by CT), patient sex and grade of neurological handicap (as assessed by Rankin scale).

The study included 50 patients (29 men and 21 women, mean age 65.52 ± 7.07 and 64.62 ± 11.83 years, respectively) who had suffered ischemic stroke 3 weeks to 6 months before the study. The Crown-Crisp experience index which consists of six scales: scales of anxiety, phobia, obsession, somatization, depression and hysteria, were used for detection of emotional disturbances.

Results showed a high prevalence of emotional disturbances in the study group. Depression was most common (36 of study patients), followed by generalized anxiety (n=29) and phobic disturbances (n=33). According to hemispheric lateralization of the cerebral lesion, a more intense emotional response was found in case of right hemispheric lesions, however, the difference was statistically significant only on the scale of somaticized anxiety (p<0.05). According to sex, a more intense emotional response was recorded in women. The difference being statistically significant on the scales of anxiety (p<0.05), depression (p<0.05) and phobia (p<0.01). An increasing tendency in the prevalence of emotional disturbances was observed with the increasing severity of neurologic deficit (p<0.05).

Study results showed a high prevalence of emotional disturbances after ischemic stroke, among which the most common is depression.

Introduction

Stroke is a major problem in all industrialized countries, as a leading cause of physical and mental disabilities. According to the World Health Organization, stroke is defined as "rapidly developing clinical signs of focal (or global) disturbance of cerebral function, lasting more than 24 hours or leading to death, with no apparent cause other than vascular origin". Mostly is coused by brain infarctions, than intracerebral haemorrhages and subarachnoid haemorrhages. Stroke affects all ages, but the incidence increases dramatically with advanced age. It is followed by various neurological disturbances, among which hemiparesis is the most constant. Patients also suffer from cognitive impairments (deficits in memory, language, orientation, attention, visuo-perceptive and viso-spatial functions). Last, but not least, we can mention mood disorders which can affect both rehabilitation and patients adjustment to disability.

Depending on diagnostic criteria the prevalence of depression in stroke patients ranges from 20 to 65% (Robinson 1997) found a high prevalence of depression for up to 2 years (Robinson et al. 1987). Many authors showed interest in post-stroke depression etiology, form, intensitiy and, recently, impact on daily living. Suenkeler et al. (2002) reported worsening of life satisfaction in positive corelation with depression (Svenkeler et al. 2002). Astrom (1996) found high prevalence of generalized anxiety in the acute stage of stroke which did not decrease significantly in the 3 years of follow-up. In some degree, methodological difficulties have been shown in conection with diagnosis of anxiety disorder (overlaping anxiety, specially phobic behaviour with normal fears because of disabillities). In many studies authors investigated relationship between localization of brain lesion and mood disorder, mostly depression, or gender and mood disorder. Some of them included pre-stroke personal and social factors as relatively important for psychological reaction to impairments and handicap.

The aim of our study was to investigate frequency and characteristics of emotional disorders after ischemic stroke, depending on: hemispheric lateralisation of brain lesion, patients gender and degree of neurological impairment.

Subjects and methods

We analyzed a group of 50 patients threated at the Department of Neurology, University Hospital Osijek, who survived ischemic stroke at least 3 weeks ago and the most 6 months ago. Most of them were attending an out patient clinic, while 6 patients were still hospitalized for stoke. Table I shows demografic charasteristics of the group.

For all of the patients hemispheric lateralisation of the brain lesion was registered with CT scan. We divided patients according to CT results in 4 groups: TACS (total anterior circulation syndrome); PACS (partial anterior circulation syndrome); LACS (lacunar syndrome); POCS (posterior circulation syndrome) (Lindgren et al. 1994). Patients with negative CT scan, and those with brain stem infarcts, were excluded from the study. We excluded patients with prior history of psychiatric disorders. Table II shows clinical charasteristics of the investigated group. For detection of emotional disorders we used Crown-Crisp Experiential Index (CCEI), which consists of 48 questions in 6 scales: scale of generalized anxiety, fobic behaviour, obsessive behaviour, somaticized anxiety, depression and hysteric behaviour (Crown and Crisp 1979).

In order to determine the presence of this disorders we used mean values and standard deviations from data of the standardization on healthy population given in test handbook (Crown and Crisp 1979), for determination the cut off score as showed in Table III.

Since CCEI is self rating scale, for the patients with impairment of vision and reading, investigator read the questions, while the patients with comprehension deficits were excluded. Degree of neurological impairment was established by modified Rankin scale (Figure 1).

Results

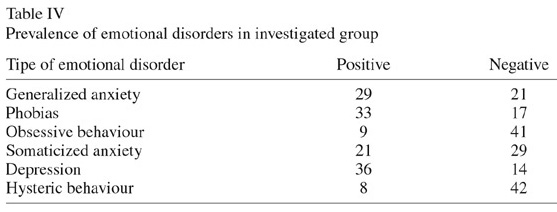

Results confirm significant presence of emotional disorders in our analyzed group. Dominant emotional disorder is post-stroke depression (36 patients), followed by generalicized anxiety (29 patients) and phobic disturbances (33 patients) (Table IV).

According to hemispheric lateralisation of brain lesion, emotional disorders are more expressed in the right hemisphere lesion than in the left, but statistically significant only on scale of somaticized anxiety (p< 0.05). (Table V).

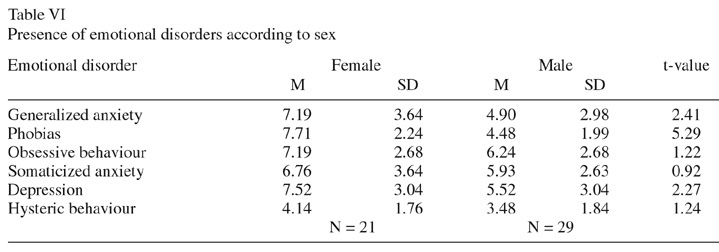

According to patients gender emotional disorders are more common among female than male patients. Statistically significant diference has been found on scale of generalized anxiety (p< 0.05), scale of depression (p< 0.05) and scale of phobic behaviour (p< 0.01) (Table VI).

Our results showed, according to Fisher's Exact Test (used because of small frequency range which demanded joining of two degrees of Rankin scale), correlation of intensity (p<0.05) of emotional disorders and degree of neurological impairment (Table VII).

Discussion

Clinical experience as well as the results of many studies show that emotional disorders after stroke can have negative influence on rehabilitation, adjustment to disabilities and longterm surviving. The etiology of post-stroke depression aroused interest in many investigators. Some of them claim that etiology of post-stroke depression is a complex mixture of pre-stroke personal and social factors and it arises as a psychological reaction to impairments and hendicap (House et al. 1991). The opposite conclusion is that stroke lesions under certain circumstances cause depression through a direct, but unknown patophysiological process. Many authors supported this, claiming that left hemisphere lesions (mostly left frontal cortex and left basal ganglia) result with depression, while right hemisphere lesion result with secondary mania. Key research in the area has been conducted at John Hopkins i.e. by Robinson and collegues, who have almost constiently found higher frequency of depression in patients with left-anterior cerebral lesion (Lipsey et al. 1986, Robinson and Szetelc 1981). Many others confirm that, while a few studies report a higher rate of depression in right hemisphere lesions (Dam et al. 1989, Feibel and Springer 1982) and the majority did not found any interhemispheric differences at all. In our study we either did not found interhemispheric diferences on the scale of depression.

After depression, anxiety is the most common emotional disorder after stroke. Clinical anxiety can be potentially serious and disabling with many consequences on a daily functioning and quality of life in general. In the study by Castillo et al. (1993) generalized anxiety disorder was found in 24% of patients with acute stroke, and most of them also had a diagnosis of major depression. Astrom (1996) registered generalized anxiety in 28% patients after stroke. She also registered that at the acute stage after stroke this anxiety comorbids with depression, and was associated with right hemisphere lesion. In our study we registered higher anxiety after right hemispheric lesion, too, statistically significant on scale of somaticized anxiety.

Some studies analyzed and showed gender differences in emotional disorders after stroke, mostly depression. According Paradiso and Robinson women were twice as frequently diagnosed with major depression as men. Women with major depression also had a greater frequency of left hemisphere lesions than men. In men, major depression was associated with greater impairment in daily activities. In women greater severity of depression was associated with prior diagnosis of psychiatric disorder and cognitive impairment. Our study also registered higher presence of emotional disorders in women than in men. It was statistically significant not only in case of depression, but also in generalized anxiety and phobic behaviour. In some degree we can connect this with socio-cultural factors, because in our culture women are more open to express their emotional problems than men.

Higher degree of neurological impairment is often conected with higher emotional problems, because disease always affect self-respect and self-confidence, especially when person needs constant help. A great problem is that this emotional changes in patients can stay unrecognized because of very common patients cognitive, especially comprehensive deficits. Difficulties in diagnosing depression after stroke may in some cases be previous history of depression, or a fact that the physical condition itself can give symptoms, such as loss of energy, loss of appetite and weight. That can lead to false diagnosis of depression as an overdiagnosis. In case of anxiety problems can be overlaping anxiety, especially phobic behaviour with normal fears due to disabillities (fear of being alone outside home, fear of illness etc.).

Differences in results between studies of mood disorders after stroke can be connected with communication deficits, anosognosia and cognitive impairments. Usually used self-rating scales in some way may contribute to either underdiagnosis or overdiagnosis. In the first place there is the problem with patients abillity to read, write or understand instructions or questions. Some patients can not express or identify emotional distress. Sometimes observed behaviour along with the valuable information from family members or other caregivers, can help in assessment.

The results showed the importance of the investigations of emotional disorders after stroke, while observed methodological problems suggest more carefull planning. Regarding that we are planning to follow a group of our patients and repeat the assessment after one and two years, including the assessment of quality of life.

References

Astrom M, Adofsson R, Asplund K. Major depression in stroke patients. A 3-year longitudinal study. Stroke 1993; 24: 976-982. [ Links ]

Astrom M, Asplund K, Astrom T. Psychosocial function and life satisfaction after stroke. Stroke 1992; 23: 527-531. [ Links ]

Astrom M. Generalized anxiety disorder in stroke patients. A 3-year longitudinals study. Stroke 1996; 27: 270-275. [ Links ]

Borod JC, ed. The Neuropsychology of Emotion. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. [ Links ]

Castillo S, Starkestein SE, Fedorof P et al. Generalized anxiety after stroke. J Nerv Ment Dis 1993; 181: 100-106. [ Links ]

Crown S, Crisp A.H. Manual of the Crown-Crisp Experiential Index. London: Hodder and Stoughton; 1979. [ Links ]

Dam H, Pederson HE, Ahlgren P. Depression among patients with stroke. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1989; 80: 118-124. [ Links ]

Erhan H, Ochoa E, Borod J, Feinberg T. Consequences of right cerebrovasular accident on emotional functioning: diagnostic and treatment implications. CNS Spectrums 2000; 5(3): 25-38. [ Links ]

Feibel JH, Springer CJ. Depression and failure to resume social activities after stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1982; 63: 276-278. [ Links ]

Feinberg T, Farah M. Behavioral Neurology and Neuropsychology. New York: Mc Graw-Hill Book Company; 1997. [ Links ]

House A, Dennis M, Morideg L et al. Mood disorders in the year after first stroke. Br J Psychiatry 1991; 158: 83-92. [ Links ]

Lindgren A, Norrving B, Rudling O, Johansson BB. Comparison of clinical and neuroradiological fundings in first ever stroke. A population based study. Stroke 1994; 25: 1371-1377. [ Links ]

Lipsey JP, Spencer WC, Rabins P et al. Phenomenologic comparison of post-stroke depression and functional depression. Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143: 527-529. [ Links ]

Robinson RG, Bolduc PL, Price TR. A two-year longitudinal study of post-stroke mood disorders: diagnosis and outcome at one and two years. Stroke 1987; 18: 837-843. [ Links ]

Robinson RG, Kubos KL, Starr LB, Rao K, Price TR. Mood disorders in stroke patients. Importance of location of lesion. Brain 1984; 107: 81-93. [ Links ]

Robinson RG, Szetelc B. Mood changes following left hemisphere brain injury. Ann Neurol 1981; 9: 447-453. [ Links ]

Robinson RG. Neuropsychiatric consequences of stroke. Annu Rev Med 1997; 48: 217-229. [ Links ]

Starkstein SE, Robinson RG. Affective disorders and cerebral vascular disease. Brit J Psychiat 1989; 154: 170-182. [ Links ]

Svenkeler IH et al. Timecourse of health-related quality of life as determined 3 and 12 months after stroke. Relationship to neurological deficit, disability and depression. J Neurol 2002; 249(9):1160-1167. [ Links ]

Address of correspondence:

Assist. Prof. Dragutin Kadoji´c MD, PhD

Department of Neurology

University Hospital Osijek

J. Huttlera 4

31000 Osijek

E-mail: kadojic.dragutin@kbo.hr

CROATIA